The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Aboriginal Rugby League in Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Aboriginal Rugby League in Sydney

Sports historian Colin Tatz has argued that Rugby League has been 'kinder to Aborigines than any other football code'. [1] Aboriginal players have been part of League teams from very early in the game's history, and from the 1960s, although the number of players was not large, the contribution of talent was considerable and included representation in the national side (Lionel Morgan) and a team captain (Arthur Beetson), among other Aboriginal players. In the senior Sydney premiership competition in 1987, there were between 29 and 32 Aboriginal players, making up 9 per cent of the players in premier and reserve grade sides. [2] In the 2005 National Rugby League Grand Final, it was reported Indigenous Australians 'will make up more than 20 per cent of the players who will run onto the field at Telstra Stadium'. [3] In 2011 the National Rugby League Indigenous Council highlighted that when any National Rugby League team takes to the field one in two players are either Polynesian or Indigenous Australians.

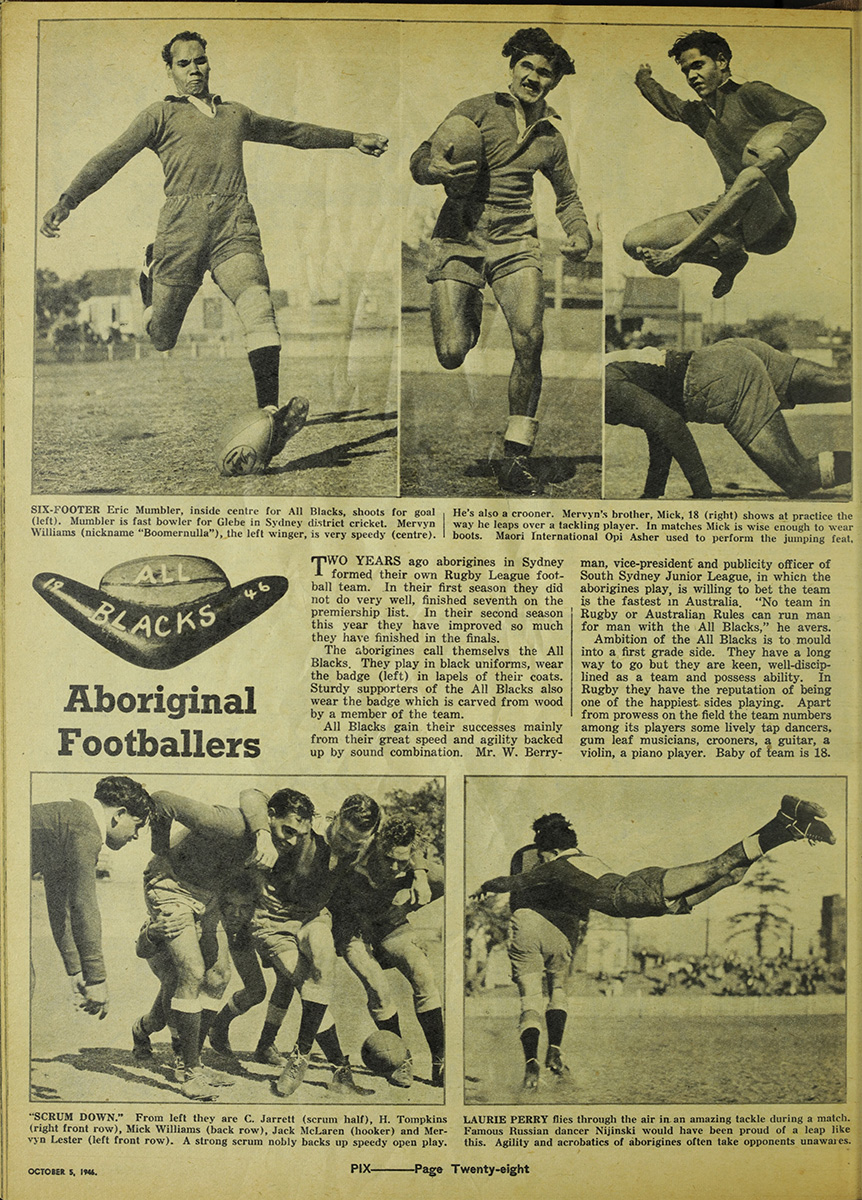

[media]This phenomenon reflects a much longer story of Aboriginal people's enthusiasm and passion for rugby league. From the 1930s, several all or mostly Aboriginal rugby league sides competed in competitions across New South Wales. In Sydney, the Redfern All Blacks and La Perouse United, competing in the Souths Juniors competition, followed this trend. Rugby League's working class origins provide one way to understand Aboriginal people's enthusiasm for the game, but there is a relative compatibility with the social lives of Aboriginal people.

Redfern All Blacks

[media]The foundation club which dominated the premiership in the early years, the Rabbitohs, was the social centrepiece of the heavily industrialised South Sydney area. South Sydney was also increasingly a base for Aboriginal families working in the factories and yards – more notably from the interwar period – and for the many who sought refuge from government control and surveillance in the bush. Work opportunities, combined with responses to government policies, saw an ever-expanding Aboriginal community and the Redfern All Blacks became a critical social and cultural hub. Redfern All Blacks, which celebrated its 75th anniversary in November 2005, has been central to the social, cultural and political history of Aboriginal Redfern. The Redfern Aboriginal community is strongly identified with the area known as 'the Block', but before the Whitlam government handed over the land to the Aboriginal Housing Company in the early 1970s, Koori families lived on Caroline Street and surrounds. The Vincent family, for example, moved from Singleton to Redfern before World War II. The Madden, Hinton, Lester, Davidson, Robinson and Lord families were also mentioned in the research as living around Caroline Street in this earlier period. These older families, who predate the 1960s wave of migration to the inner city, strongly identified with Redfern All Blacks and this connection endures today. For example, the Vincent family has a four-generation association with Redfern All Blacks. Ray Vincent recalls being carried out on his father's shoulders at Redfern oval before World War II, when he was about four years old. [4] He spoke of his uncles and brothers playing for Redfern All Blacks and now his nephews play, including Nathan Merritt. Many other families have similar cross-generational associations with the club.

Further to this long-standing kin-based connection, Redfern All Blacks also came to be a home for many Aboriginal people who spent their early life in institutions as a result of the state government's child removal policy, particularly former residents of Kinchela Boys Home. At the 2002 Knockout Carnival – an event introduced later in this entry – the 'Kinchela Boys Home Ken Brindle Memorial Shield' was presented to the most promising player in the grand final. The shield honoured Ken Brindle's association with Redfern All Blacks and paid tribute to the association of former Kinchela residents and their special place in the Redfern community. In a ceremony prior to the grand final, the former residents walked on to the oval and were presented to the crowd as a smoking ritual was carried out. While the grief and trauma of those former residents was apparent for all to see, the ceremony affirmed their significant relationship to 'place'.

Redfern All Blacks has operated as more than a sporting team, as one community member with a 60-year association with Redfern All Blacks explained: 'When you think about it, the Blacks have been political since way back when ... without realising they were making a statement' and that 'the Blacks are the longest running political organisation that we have':

Politics is always a part of what we were doing but it was never the driving force. It was more about sport and more about family and more about community. And I think that's the way it's got to be. [5]

Rugby League was an early vehicle for Aboriginal people to gather and organise in an otherwise authoritarian and controlled environment of restricted movement and association. The football competitions, and the social and political interactions that ensued, may also have served as impetus for relocation to the city, if only because of the possibility to earn money through the game. Redfern All Blacks President, Ken Brindle, writing in New Dawn in June 1970, confirmed this sentiment in saying:

when youngsters first arrive in Sydney, a club consisting of their own people, where they can become involved and feel part of, assists them immensely to settle down in the first crucial ... weeks.

He went on to say that the club,

affords them good training in management ... and responsibility [and often] become involved in their players' problems [and] ... help to find employment, accommodation and quite often legal assistance for minor offences'. [6]

In 1969 Redfern All Blacks travelled to Moree, Casino and Bega to participate in NADOC (sic) week regional knockouts. This was covered in New Dawn with a picture of Redfern All Blacks on the front cover in June 1970, wearing red and white jerseys, after gaining sponsorship from St George Rugby League Club. [7] They also toured New Zealand in 1971 with support from the National Aboriginal Sports Foundation and of this Brindle said:

the Commonwealth Office of Aboriginal Affairs does realise the value of Aboriginal participation in sport, ... all the placard waving, demonstrating and demands will not open one tenth of the doors that can be opened through sport. [8]

Ken Brindle was involved in a range of community activities, including proposals to the Council for Aboriginal Affairs for a community centre. Similarly, Brindle, in organising the New Zealand tours, saw them as cultural exchanges and community development. Ken Brindle saw Redfern All Blacks as a means to build community and cultural capacity and pride. The football teams carried with them far greater significance – they were vehicles for community development and the re-forming of new communities.

Koorie United

Whereas Redfern All Blacks reflected particular patterns of occupation and migration, the formation of Koorie United from 1970 reflected new and changing communities. This can largely be understood in terms of the late 1960s pattern of migration of Aboriginal people to Sydney, particularly to Redfern and the inner city. While older families who migrated to Redfern in the pre-war era were affiliated with Redfern All Blacks, and La Perouse was similarly geographically linked with the south west of the city and South Coast families, Koorie United reflected different cultural groupings and social and economic experiences.

Koorie United was formed in response to the rapidly expanding Sydney Aboriginal community. The established Sydney-based Aboriginal sides, the Redfern All Blacks and La Perouse (Blacks or Panthers as they were sometimes called), were aligned with the South Sydney football district. There were simply many Aboriginal men looking for a game of football and so Koorie United joined the 'rival' Newtown Jets district, with sponsorship from Marrickville Council, where some of the committee members worked. They emerged with something of a splash, taking out the premiership in 1974.

The Koorie United committee members were connected through kinship and the shared experience of relocating to the city. Bob Morgan, Danny Rose and Bill Kennedy hailed from the north-western New South Wales town of Walgett in Gamilaroi country. Bob Smith and Victor Wright had relocated from Kempsey on the New South Wales north coast, and while the late George Jackson was based in Sydney, he also had connections with Gamilaroi as his wife was from Coonabarabran, as was Victor Wright's. This kinship connection extended to the inaugural President Jimmy Little – his wife also hails from Walgett. The formation of Koorie United can be read as a response to established kin and community affiliations as well as the desire to create means by which new and changing communities could associate and organise – and play football.

The Knockout

The Koorie United group were responsible for a significant innovation in Aboriginal Rugby League – they instigated the Annual New South Wales Aboriginal Rugby League Knockout Carnival in 1971. The Knockout flowered in the context of the new and growing Sydney inner-city Aboriginal community of the late 1960s and early 1970s and can also be understood as part of a much longer tradition of participation by Aboriginal people in the football code of Rugby League. Since this time the Knockout has grown to a four-day carnival run by and for the Aboriginal community each long weekend in October and attracts about 100 teams in the junior, women's and men's competitions. It is widely described as a 'modern day corroboree' for reasons that will be detailed later, as 'bigger than Christmas', and it is the largest gathering of Aboriginal people in the country.

The idea of holding the Knockout was first discussed at a meeting of Koorie United at a well-known gathering place for Kooris in Redfern in the 1960s: the Clifton Hotel. The Koorie United committee proposed holding a statewide Knockout competition in Sydney and while there had been many town-based knockout football and basketball competitions, the establishment of the Knockout set out with some different objectives. Bob Morgan says:

Our concept at the time was to also have a game where people who had difficulty breaking into the big time would be on show. They could put their skills on show and the talent scouts would come and check them out. [9]

The Knockout was formed to provide a stage for the many talented Aboriginal footballers playing at the time who were overlooked by the talent scouts. Although there were some notable exceptions, like Bruce (La Pa) Stewart playing on the wing for Easts, Aboriginal footballers experienced difficulty breaking into the 'big time'. It was thought the Knockout would provide a chance for Aboriginal footballers to shine, where they had previously been overlooked because of racism and lack of country-based recruitment.

Secondly, as original committee member Bob Morgan said:

The Knockout was never simply about football, it was about family, it was about community, it was getting people to come together and enjoy and celebrate things rather than win the competition football.

Bob Smith, founding member of the Knockout, described the event in the following way:

It's almost got the same sort of feel about it, like when you go to funerals. It's not the same but it's still an opportunity for people to meet … an opportunity for people to meet and renew friendships. [10]

The first Knockout in 1971, hosted by Koorie United at Camdenville Oval, St Peters, attracted seven teams: Koorie United, Redfern All Blacks, Kempsey, La Perouse, Walgett, Moree and a combined Mt Druitt / South Coast side. For the first few years Koorie United hosted the carnival and it was won by La Perouse United (1971), Redfern All Blacks (1972–73), Koorie United (1974) and Kempsey All Blacks in 1975. With Kempsey the first non-Sydney side to win the Knockout, it was decided that the winning team would host the Knockout the following year. In 2010, 40 years later, there were 100 teams competing at the Knockout, hosted by Walgett and held on the Central Coast.

Over the years, the size and complexity of the event has greatly increased. Bob Smith explained that in 1971 he hand-drew A4 cardboard signs and posted them around Redfern. The nomination fee was $5 and the winner 'took all' of the $35 prize money. In 2010 the entry fee was $1,500 and the winning team collected $60,000 in prize money. There were also second, third and fourth place cash prizes. In addition, the women's Knockout, which for a long time was merely a side event, attracted 12 teams in 2010 with the crowd-pleasing final played on the Monday of the October long weekend. Aside from Sydney, it has been hosted in the rural towns of Dubbo, Armidale, Bourke, Walgett and Moree and in the coastal communities of Lismore, Kempsey, Maitland, Nambucca Heads, Tweed Heads and the Central Coast.

The Knockout carnival can be understood as cultural performance and expression, where kinship-based modes of organisation merge with state-shaped communities, and where people gather for courtship and competition. The football is reminiscent of a four-day traditional ceremonial dance and celebration, but also enables new social and cultural practices to emerge. It is an opportunity for families to gather, reunite as a community and barrack for their hometown and mob, and commemorate past glories and those who have passed on. The Knockout is fiercely contested – world-class, tough football is on display and victory is a lifetime highlight for players and communities.

South-West Metropolitan Waratahs

Danny Thorne was motivated to form the South-West Metropolitan Waratahs in 2002 to compete in the Annual Knockout carnival. [11] Thorne explained that, in the absence of a traditional or tribal association in the Campbelltown area, in the south-west of Sydney, it was appropriate to come up with a team emblem that was representative: the waratah, traditional to the area and the New South Wales floral emblem, captured the whole Aboriginal community. He formed the team to build a greater sense of community and to strengthen younger players in their Aboriginal identity. For Thorne, the Knockout is an opportunity for young players to meet their extended families where those connections, which are central to identity and culture, haven't been renewed. Sometimes, he says, 'where you are second generation born in the city, you can lose those contacts with your country'. Thorne set out to build a sense of community and connection in Campbelltown and south-west Sydney amongst Aboriginal people, parallel with his own experience of migrating from Walgett to South Sydney and playing with Koorie United and at the Knockout.

References

Heidi Norman, 'A modern day Corroboree: towards a history of the New South Wales Aboriginal Rugby League Knockout', Aboriginal History, vol 30, 2006, pp 169–186

Heidi Norman, 'An unwanted Corroboree: the politics of the NSW Aboriginal Rugby League Knockout', Australian Aboriginal Studies, vol 2009, no. 2, pp 112–122

Colin Tatz, Obstacle race: Aborigines in sport, New South Wales University Press, Kensington NSW, 1995

Notes

[1] Colin Tatz, Obstacle race: Aborigines in sport, New South Wales University Press, Kensington NSW, 1995, p 10

[2] Colin Tatz, Obstacle race: Aborigines in sport, New South Wales University Press, Kensington NSW, 1995, ch 8

[3] Sydney Morning Herald, Weekend edition, 1–2 October 2005, p 7

[4] Interview with Ray Vincent, conducted by Heidi Norman, 25 August 2004, Redfern

[5] Interview with Ray Vincent, conducted by Heidi Norman, 25 August 2004, Redfern

[6] New Dawn, September 1970, p 5

[7] New Dawn, June 1970, cover

[8] New Dawn, June 1970, p 2

[9] Interview with B Morgan, conducted by Heidi Norman, 30 May 2004, The Entrance NSW

[10] Interview with Bob Smith, conducted by Heidi Norman, 19 September 2004, Kempsey NSW

[11] Interview with Danny Thorne, conducted by Heidi Norman, August 2004, Campbelltown NSW

.