The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Drag and cross dressing

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Drag and cross dressing

The 1995 movie Priscilla Queen of the Desert brought to world attention the high profile enjoyed by drag queens in Sydney, although Australia's most famous cross-dresser, Dame Edna Everage, had been treading the world stage for years.

The nineteenth century

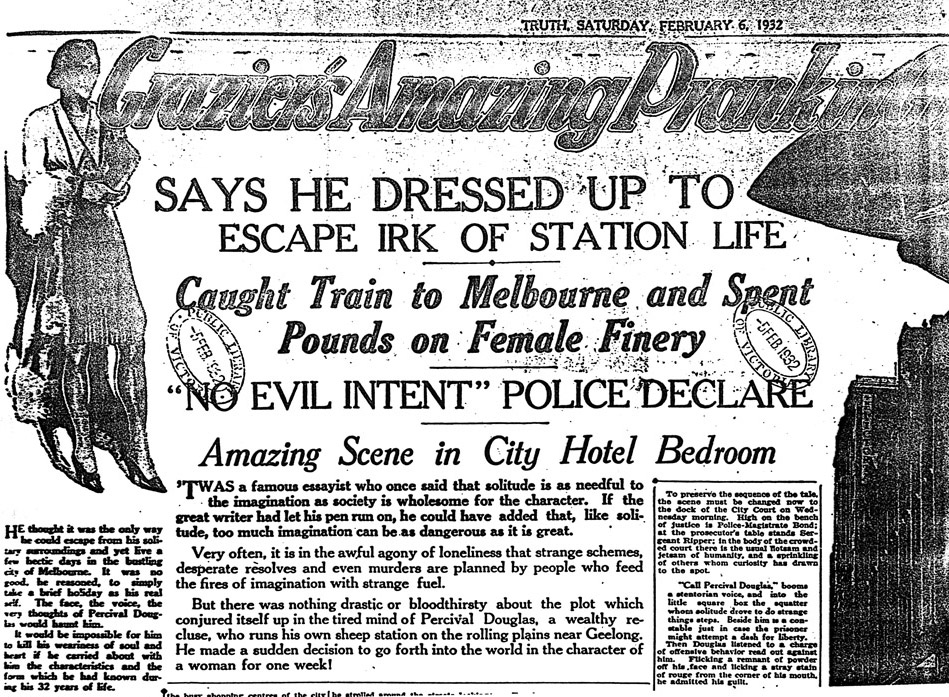

During the nineteenth century, [media]wearing the clothes of the opposite sex aroused extreme distaste and incomprehension. It was prohibited by the law, yet there could also be ambivalent attitudes expressed by those in authority as to what might be deemed 'unnatural behaviour.'

In 1835, the convict, Edmund Carmen, was caught by police in countryside near Wollongong, 'dressed in a woman's gown and cape.' He was found guilty of improper conduct, given 50 lashes, and sent back to Sydney with the proviso that he was 'not to be assigned again to this District.'

Yet four years later, when police arrested a woman for drunkenness in George Street, and then found that she was, in fact, a he, they simply sobered him up and sent him on his way. Perhaps city ethics were more tolerant: in Sydney during the 1850s, both locals and visiting sailors tried to free a fellow sailor from the watch-house in the Rocks – he had been arrested for wandering around the area in female attire.

Sporadic references to public cross-dressing certainly appear in Sydney's history. [media]Sometimes it was a celebrity of the times, such as Steve Hart, of the infamous Kelly gang. The local newspapers reported that he was riding around disguised in female clothing. Such scenes have been strikingly portrayed in Sidney Nolan's Kelly Series paintings.

Less tolerance

But [media]at the end of the nineteenth century, news of the Oscar Wilde scandal in London burst upon the city. Sydney's newspapers enlightened readers about the famous playwright's same-sex predilections and liaisons with post office messenger boys. His foppish style of dress and extravagant, eccentric manner further fanned the flames. These allegations came to light in the libel case that Wilde unwisely brought against the Marquis of Queensbury, who had publicly accused him of being a 'somdomite [sic]'. Homosexuality, at that time equated with effeminacy, was seen as undermining the manhood of the nation, and effeminate men, especially those who cross-dressed, were deemed worthy of public rebuke. [media]One Sydney scandal sheet condemned those men,

whose presence is advertised by an effeminate style of speech and the adoption of the names of celebrated actresses … and that part of College Street from Boomerang Street to Park Street is a parade for them. [1]

But maybe these effeminate, drag-wearing men, like those arrested in 1917 at their house in Margaret Street, were doing it for their own private pleasure.

Cross-dressing as entertainment

Although there were laws against men appearing in women's clothing, it was usually condoned if confined to the theatre. As in Britain, the 'Dame' role in pantomime was often played by men, and in the more mainstream theatre young males had, certainly since Shakespeare's time, played female roles. This was an avenue for cross-dressers to explore, and in the early years of World War II nightclubs sometimes featured local 'stars' such [media]as 'Lea Sonia'. S/he appeared regularly in drag at the Diamond Horseshoe Club in Oxford Street, Woollahra.

Yet care had to be exercised. At the Ziegfeld Club in King Street in the city in 1942, Harry Foy, 'an accomplished nightclub dancer' who 'dressed in a mix of men's and women's clothes, flirted with many of the men there, as was his habit.' Unfortunately, the American sailor whom he tried to kiss was not amused, and knocked Harry to the ground. Tragically, Foy died the next day. [2]

Another paradox of the history of drag also came with the war. Many of the men who joined the show troupes that entertained soldiers in the war zones of the Pacific and Asia played the role of 'femmes', as they were known. And many of the best of them were those who had prior experience of throwing on a frock. Such behaviour might have got them thrown into jail back in Sydney in peace time, but wartime needs saw them paid to entertain the troops.

[media]Wartime Sydney also saw a continuation of some of the large-scale balls, such as the Artists and Models Balls, notorious from the 1920s, where those who cross-dressed could appear fairly safely in public. Jon Rose's At the Cross has some wonderful descriptions of such balls. In one, the police had a running battle on their hands with a large drag queen, named Melba, who was incensed when the raiding police interrupted her on stage in the middle of her favourite song.

Changing attitudes

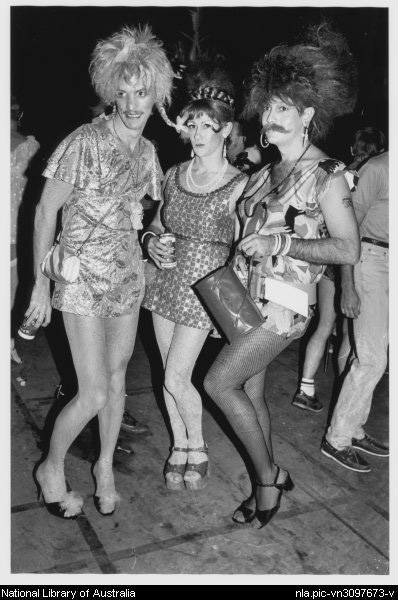

Yet things loosened up in the postwar era. The war had made many men aware that they were not alone in their dissident sexualities, and after the war what was termed 'camp life' boomed, albeit discreetly. Newspapers were not shy in reporting such things as the sex change of American serviceman George Jorgensen, who became Christine Jorgensen. [media]New ideas about the fluidity of gender and sexuality were also noted, as were the Sydney parties where men dressed as women, with names borrowed from the movie stars of the era. And they had the photos to prove it. Sydney was titillated, rather than shocked.

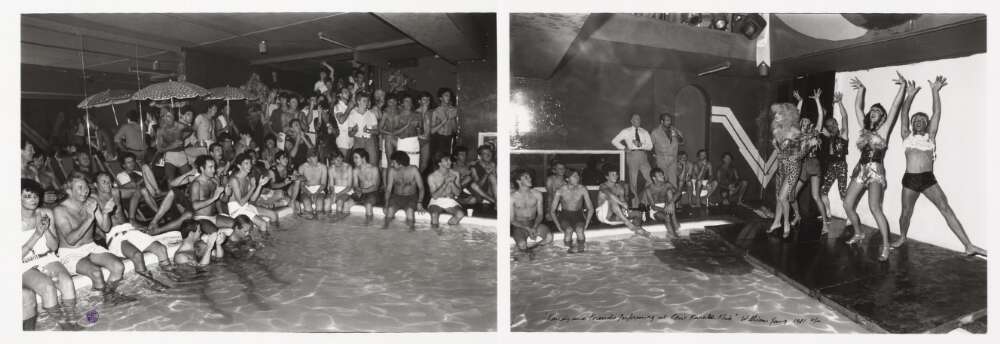

Gradually, a series of clubs which featured drag shows as their drawcard began to appear. [media]They turned up in a variety of places and included the Stork Club near Tom Uglys Bridge in Sylvania Waters; Karen's Kastle in Cleveland Street, Redfern; Kandy's Garden of Eden in Newtown; and the Annexe and the Jewel Box, both in Kings Cross. Probably most famous of these was Les Girls, which started out as a place of entertainment for the gay world, but over time became the naughty night out for suburban hens' parties.

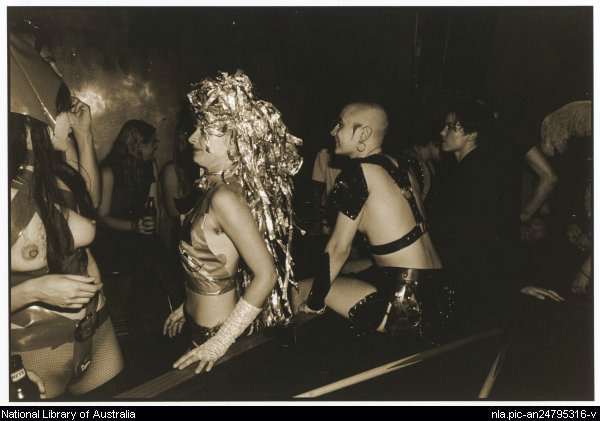

[media]But not all drag shows were anodyne chorus-lines of leggy men wearing lots of feathers and sequins and not much else. [media]The Purple Onion in Kensington featured Beatrice, with such satirical shows as the Sound of Mucus, a hilarious send-up of the Sound of Music. Kandy was another star of such shows, which, as theatre critic Katharine Brisbane noted, were 'rare and authentic burlesque; shrewd, witty, obscene, and always up to date.' [3]

The style of the drag queen changed over time. While there was always a demand for those leggy boys who could mime realistically, some – like Carlotta and Carmen – became personas in their own right. And those who could sing and create their own style often developed their own following. [media]Female role models, such as Shirley Bassey and Dusty Springfield, are variously blamed for the high level of hand movements that were de rigueur in drag shows from the 1970s.

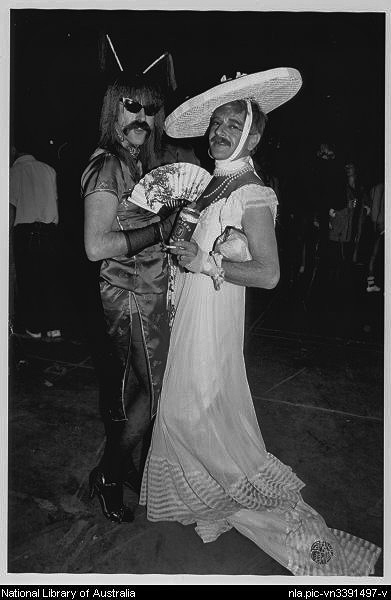

Other media also began to feature drag, often in these new manifestations. The Auntie Jack Show on ABC television had a bewhiskered, overweight motorbike-riding drag queen as its star. The counter-cultural revolution and the gay liberation movement saw the advent of 'radical drag', which joined smart frocks and stilettos with a hairy chest and designer stubble.

The visual impact of drag was also utilised in various 'safe sex' campaigns that the state's health authorities implemented as a response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic that hit Sydney from the early 1980s. The Safe-Sex Sluts were a sassy group of smiling 'tarts', who appeared at various gay events, handing out literature and condoms.

Cross-dressing today

Cross-dressing in public no longer causes fear and consternation among the citizens of Sydney. [media]Drag lost its bite when troupes like Les Girls began to appear at suburban Leagues clubs. The popular live television show The Footy Show wouldn't be half as much fun if the football fans didn't feature drag more than occasionally.

There continue to be drag queens who embody the traditional Carmen/Carlotta style of drag. [media]Others embrace satire, as seen in some of their names, such as Carmen Geddit, Maude Boat, Minnie Cooper, Sandy Toggs, Victoria Bitter, Kitty Glitter, Kirsten Damned, Tess Tickle and Farren Heit.

References

Jon Rose, At the Cross, Deutsch, London, 1961

Clive Faro, Street seen: A history of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000

Garry Wotherspoon, City of the Plain: history of a gay subculture, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991

Michael Pate, An Entertaining War, Dreamweaver Books, Sydney, 1986

Notes

.