The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Film

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Film

From the beginning of the twentieth century, Sydney defined cosmopolitanism and modernity in the national imagination, and central to this image was the cinema: its technology, its architecture, its stars, its marketing and, most of all, the stories it circulated to its audiences about Australia and the world. Going to the cinema embodied the bright lights, the romance and, for some, the vulgarities of city life.

It is difficult to define a genre of Sydney film. Throughout the twentieth century, Sydney provided the backdrop for a host of ideas about the city, and later suburbia, ideas that were integral to the national project to create and instil a sense of Australianness. Sydney came to embody a quality on the edge of the national mainstream, a 'tinsel town' of cultural bankruptcy and hedonism. But distinctive stories about the city itself, in the way that other cities developed their own twentieth-century 'symphonic' representations, are rare. Important exceptions to this are the Sydney films made in the 1930s and 1940s under the official auspices of the Commonwealth government for the purposes of marketing the nation. Migrant film also emerged as an important category of cinema from the 1970s, and through its exploration of the diversity of Sydney, has made the city central to the understanding and construction of Australian multiculturalism.

This essay explores the historic beginnings of cinema in Sydney, and the experience of going to the pictures for the people of Sydney. A broad spectrum of films that have emerged from the industry's beginnings is surveyed, with a view to understanding the cinematic city in the twentieth-century cultural imagination. We also examine the role Sydney has played in the production and exhibition of cinema in both the national and international arenas.

Going to the show – the early years

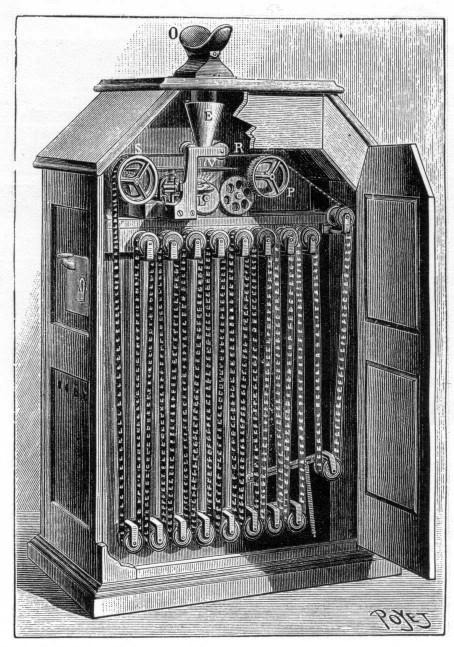

The presence of a film culture in Sydney dates back almost as far as the invention of modern cinema itself. [media]Over a year before the Lumière brothers first projected a moving picture onto a big screen for a public audience, Sydneysiders were treated to the cinema's earliest manifestation with the Australian premiere, in 1894, of Thomas Edison's kinetoscope, set up in a converted shop in Pitt Street. Customers were invited to pay their five shillings at the door and look through a lens at 20-second pastiches of filmed life. Twenty-two thousand people visited the Kinetoscope Parlour in its first five weeks, [1] marking the beginning of Sydney's love affair with the cinema.

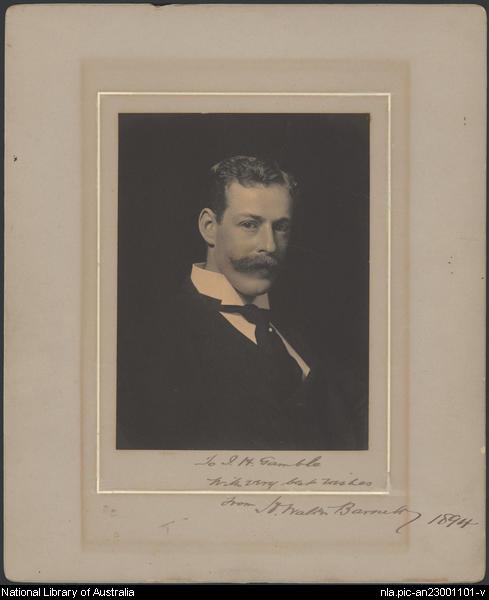

'Slice of life' actuality films were the earliest forms of Australian cinema, tending to feature scenes of city life. [media]In 1896, Passengers Alighting from Ferry 'Brighton' at Manly, made by the pioneering team of Marius Sestier from Lumière and Australian photographer Walter Barnett, was screened at a Sydney venue in Pitt Street. For the first time in Australia, watching a film became a collective experience shared by others at the same sitting. These very first picture theatres were temporary venues, often little more than tin sheds, hired out for special evenings of entertainment made up of actualities, newsreels and short comic sketches. From the early 1900s, the establishment of programs dominated by a 'feature' film shifted the place of cinema in the urban cultural landscape, cementing 'the pictures' in the daily lives of Sydneysiders.

[media]From its earliest years, the cinema found its most natural home in the suburbs, providing a suburb with its own amenity and meeting place. [2] The venues were often basic, but films were cheap and accessible. The introduction of continuous screenings, first by the Colonial in Sydney in 1906, with non-stop films running between 11 am and 11 pm, [3] made it easier for women to patronise the cinema during the day, often with young children in tow. Just as crucially, the introduction of six o'clock closing for public bars during the war years meant that the cinema was often the brightest light in town after dark. For young women, especially as they began to gain more financial independence during and after World War I, the cinema was the one place considered safe and acceptable to visit unchaperoned, and it was 'the flicks' that often presented the opportunity to mingle with members of the opposite sex. By 1914, cinema-going was firmly established as a suburban activity and as Sydneysiders' favourite form of leisure and entertainment.

Sydney's cinema architecture developed accordingly, with the construction of grand 'picture palaces' in the city's centre, under the direction of entrepreneurial showmen such as JD Williams, TJ West and Cozens Spencer.[media] The Crystal Palace in George Street was an early example, a lavish affair with slot machines, a soda fountain and ice-cream bar, air conditioning, a gymnasium, and a wintergarden cafe complete with electric fountain and tables with their own telephone connections. [4] The most spectacular of the picture palaces was the State Theatre in Market Street. One entered through a Gothic entrance hall and ascended a curving marble staircase, passing art galleries in the auditorium, velvet lounges, an aquarium and, in the theatre itself, Romanesque statues and a magnificently enormous chandelier.

Early film production

Filmmaking in Sydney before World War I was enormously prolific. This was the first 'golden period' of Australian film, which between 1907 and 1912 saw the production of at least 90 feature films, many of them in Sydney. This period of creativity was made possible by the fact that supply of American features was spasmodic and exhibitors were still independent. [5] However the formation of 'the combine', the amalgamation of two powerful companies – Union Theatres and Australasian Films – radically changed the landscape of Sydney cinema, gradually squeezing out independent producer-exhibitors and flooding the market with American imports.

In the 1920s, Sydney was still a hub of filmmaking activity, but the films that were created in the city were only rarely about the city itself. Like many of Sydney's artists, filmmakers were engaged in forging a unique sense of Australianness, and this was believed to exist and flourish in the landscape of the bush. Yet pictures celebrating the outback were as much a comment about the city as they were about the bush, even when the city was mostly absent. If the bush represented a tough but pure life where the Australian 'type', imagined in a similar vein, could thrive, the city was by contrast a hotbed of dissipation and vice. The myth of the bush was, paradoxically, a myth of the city.

[media]In Franklyn Barrett's The Breaking of the Drought (1920), Sydney, with its cigarette-smoking vamps, its gambling and its tricksters, becomes a trap that sucks in a young innocent from the country, corrupting and ruining him and his family. Barrett's film of drought-ridden New South Wales remains one of the only records of this devastating drought; equally, his documentary scenes of the slums of Sydney and its bohemian night life are a vivid portrait of the inner city at this time. Raymond Longford's timeless classic The Sentimental Bloke (1919) charts the courtship of the bloke and his true love Doreen, from Sydney's gambling dens and slums to an idyllic life managing an orchard in the country. Despite the film's final message that to leave the city is to find happiness, there is something distinctly, and uniquely, charming about Longford's depiction of the shabby inner city suburb of Woolloomooloo with its lively working-class characters and their distinct urban jargon. [media]The film became an instant hit with Australian audiences, even outdoing the rival American productions on offer at the time, and quickly became a benchmark of quality Australian cinema.

Selling Australia

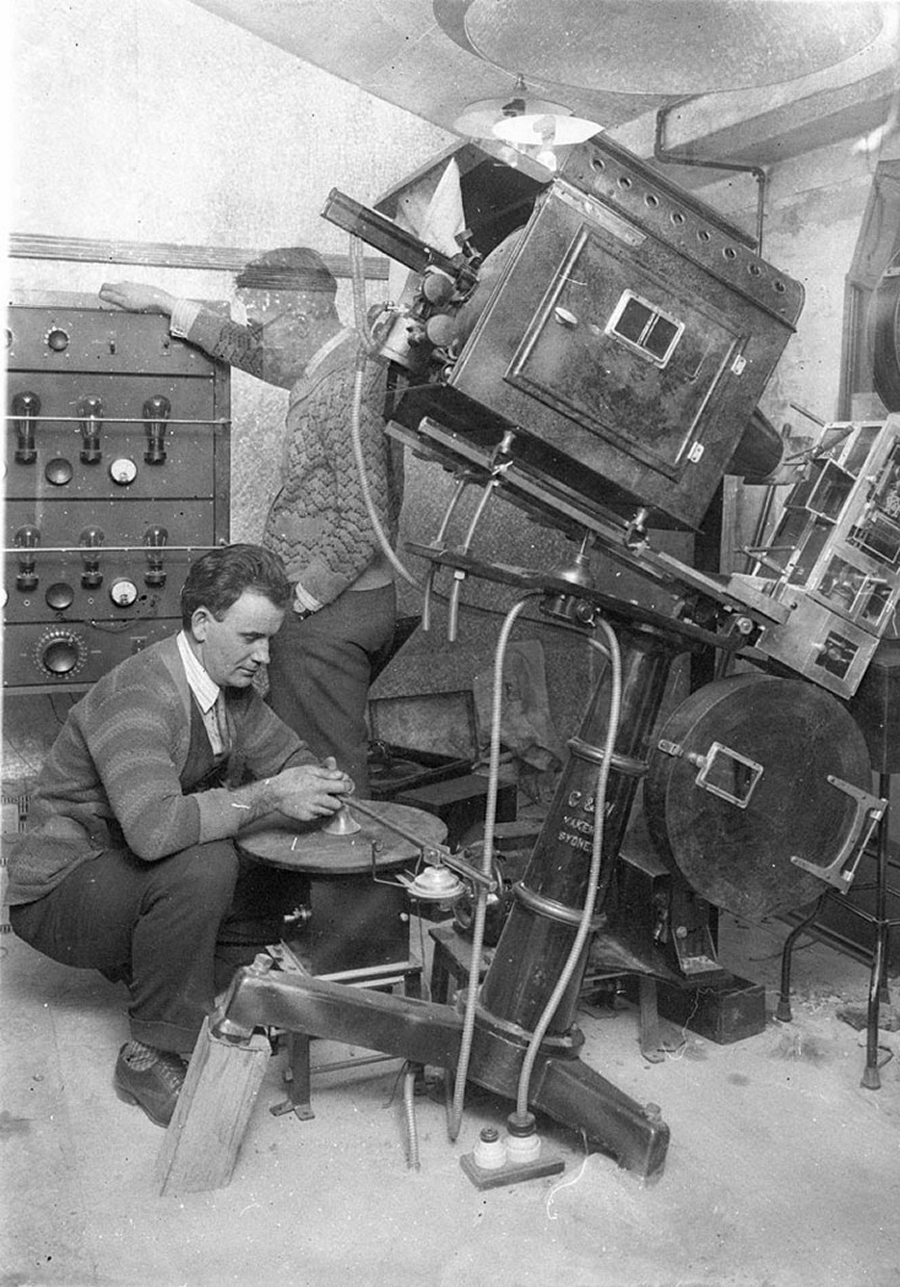

In the late 1920s, the introduction of the 'talkies' [media]cemented the American hold over Australian cinema, and by 1927, 90 per cent of all films screened in Australia came from America. Without adequate support and unable to compete with cheap American products, independent film production dried up in the 1930s. Recognising the enormous potential of film as a marketing tool for promoting national interests, the Commonwealth government instead focused on producing its own propaganda films. [media]These were designed to promote industry, trade, tourism, and to attract British migrants, and Sydney was quickly established as the international 'face' of Australia. Sydney was depicted as modern and fun-loving, the centre of both commerce and leisure, usually encapsulated in these representations by the twin icons of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and the city's beaches. This is Australia (1932), for example, produced by the official cinematographer of the Cinema and Photographic Branch, Bert Ives, focuses on Sydney's beaches and its lifesavers, who assume 'heroic proportions' by being likened to the Anzacs at Gallipoli with their daring, 'manly spirit'.

Frank Hurley's A Nation is Built (1937) was the most significant government film of the interwar era, made as the official documentary for the sesquicentenary of British colonisation of Australia in 1938. Hurley's 'flair for portentous imagery and rhetoric' [6] is put to full use in the film, in which he makes Sydney's cityscape a monument to the building of the modern Australian nation. Once again the lifesavers have a starring role, described in the commentary as 'nation builders of the city'. The film had enormous success overseas, and was reportedly so popular at the Glasgow Empire Exhibition that it was shown day and night.

If Sydney's beaches signified a pleasure-loving, vigorous young nation, the Sydney Harbour Bridge, opened in 1932, captured the cinematic imagination in other ways. Sydney's Harbour Bridge (Bert Ives, 1932) displays the bridge at different stages in the six-year construction process. The commentary highlights the bridge as symbolic of the city and the nation's transition to a new era of technological progress and prosperity. [7]

From the 1930s, the Sydney Harbour Bridge became the pre-eminent image to represent the triumph of Australian modernity. [media]The most prolific and successful Australian filmmaker of the 1930s, Ken G Hall, used the bridge extensively to illustrate Sydney's changing urban environment and modern Australian identity . In It Isn 't Done (1937) he juxtaposed the Sydney Harbour Bridge with architectural icons of the 'old country', such as London bridge, in a film that sought to affirm the natural and moral superiority of Australians over British 'high society'. However the bridge has also been used less triumphantly. In Broken Melody (Ken G Hall, 1933) the impoverished heroine attempts to take her life from the base of the bridge. Similarly in Turkish-Australian director Ayten Kuyululu's The Golden Cage (1975), a young Turkish immigrant tries to kill himself within view of the Harbour Bridge, succeeding in doing so on his second attempt. Here the bridge represents the chasm between the city's promise of assimilation and material success, and the cruel reality of its shallow hedonism and the alienation of the migrant. [8]

Sydney as visual spectacular continues to market the nation to the rest of the world. In the promotional three-minute video made to assist Australia's bid for the Olympic Games, Share the Spirit (Sydney Olympics 2000 Bid, 1993), Sydney is showcased as a friendly idyll of sun, surf and the competitive spirit embodied by the Games. This time however, the faces of a more inclusive Australia feature, and the film opens to the sound of a didgeridoo and closes with the iconic Sydney Opera House. [9]

The postwar era of Sydney film

The first mass settlement migration schemes of the postwar era brought thousands of migrants to Australia to labour on its construction sites. They 're a Weird Mob (1966), directed by the Englishman Michael Powell, details the experience of an 'accidental' Italian immigrant, Nino Culotta, a journalist who takes work as a builder's labourer in suburban Sydney. The construction site becomes a formative location for his experiences of assimilating into Australian life and learning the touching and often hilarious rules of mateship. The film humorously explored the seemingly incomprehensible elements of 'being' Australian, and reflected the dominant assumption of the era, that assimilation was both desirable and possible, a simple process of shedding one's own culture on arrival and adapting the 'Australian way of life'. Shots of the harbour, the city, Bondi Beach and the building frenzy in the suburbs figure prominently in the film. Credited with generating the Australian film revival, it had enormous local appeal at a time when local production was virtually non-existent.

Local film production in the postwar years was minimal, and overall, the sorts of films exhibited in Sydney tended to be standard Hollywood offerings. But thanks to a growing number of film societies and the State Film Council library, non-mainstream films were also screened. [media]In 1954, the opportunity for watching alternative cinema and unseen 'classics' was enhanced with the establishment of the Sydney Film Festival – the second oldest in Australia and one of the world's longest running. [media]Film festivals have now become an important Sydney institution – hardly a week goes by without a screening event such as Tropfest, Flickerfest, Queer Screen, the Underground Film Festival or the Spanish, Mexican, Russian, Greek, Italian, Jewish and French film festivals playing in open air cinemas, pavilions, pubs and dedicated arthouse venues. Touted as the largest short film festival in the world, Tropfest now attracts hundreds of short film entries and an audience of hundreds of thousands to its open air screenings every February. It has become internationally renowned for showcasing emerging new talent, judged by illustrious names in the industry, and for the quirky nature of Sydney's film culture. [10]

Experimental filmmaking emerged during the mid-1960s with the Ubu film movement, a group that took its cue from the European avant-garde. Ubu Films, the Sydney Filmmakers' Cooperative and, in the 1980s, the Sydney Super 8 Film Group were instrumental in developing a diverse and vibrant alternative film culture. However, with the rise of Sydney as an international filmmaking hub in the 1990s, the perversity of government film funding, and the closure of independent arthouse venues, the alternative feature film culture contracted.

The renaissance of local film

In the 1970s the arts received a boost under the new Whitlam-led Labor government, which sparked a welcome resurgence in Australian film. Part of the new strategy included the establishment of the Australian Film Television and Radio School in Sydney, still the most successful school of its kind in the country. Another part was the provision of funding for local filmmakers, and a new Sydney-based Australian Film Commission was given the task of selecting possible projects for assistance. The films chosen tended to fit popular nationalist themes: the outback and war were typical settings for the new wave in Australian cinema. Film was still regarded, officially at least, as a tool for instilling and promoting a collective sense of Australianness.

Period pieces were also popular. Caddie (Donald Crombie, 1976) charts the life of a woman struggling to make it on her own in the Sydney of the 1920s and through the Great Depression of the 1930s. Sydney's rough working-class pub culture is vividly recreated in the film, including one memorable scene of the famous 'six o'clock swill'. A series of sequences depicts the evictions, homelessness and unemployment of the Depression years. A criticism of the film was that these recreations were so theatrical, the attention to period detail so stylised, that the film itself became an exercise in 'décor' rather than good drama. [11]

[media]One of the most famous Sydney films of the 1970s revival was Don 's Party (Bruce Beresford, 1976), based on a play by David Williamson. Set on the night of the 1969 federal election, the film is a 'micro study of middle class hypocrisy', [12] a cynical portrait of middle Australia over the course of the night that Whitlam came close to overturning 20 years of conservative rule. A suburban couple host a party at their home to celebrate what they hope will be a Labor victory. As the re-election of the conservative government becomes a surety, the party descends into a chaos of drunken debauchery, wife swapping and general mayhem that cynically exposes the political shallowness of the 'Vietnam generation', the university-educated elites who lived on Sydney's well-to-do north shore and whose radicalism was little more than posturing.

The Sydney–Melbourne divide is a time-honoured distinction in Australia's cultural geography, and the rivalry between the country's two largest cities is part of an ongoing conversation about the differing 'configurations of nation'. Don's Party was originally set in Melbourne: relocating the film to Sydney was a comment on the city's cultural bankruptcy and self-absorption in contrast to a more serious and moral Melbourne. This theme was carried through in a later film written by Williamson, Emerald City (Jenkins, 1988), in which Sydney is negatively contrasted with Melbourne, and depicted as 'New York without the intellect'. [13] Sometimes this was reversed. Ray Lawler's theatre classic, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll (1955) was adapted in 1959 for the screen with American actors in the leading roles. Here, Sydney replaced the original Melbourne setting with the characters relaxing at Bondi Beach rather than moping around dreary Melbourne. Another film that also features Sydney as desire is Canadian Ted Kotcheff's sublime Wake in Fright (1971). Set in the parched red outback, Sydney appears as a dream, a shimmering phantom that equates the protagonist's longing for home with sex on the beach and a cold beer.

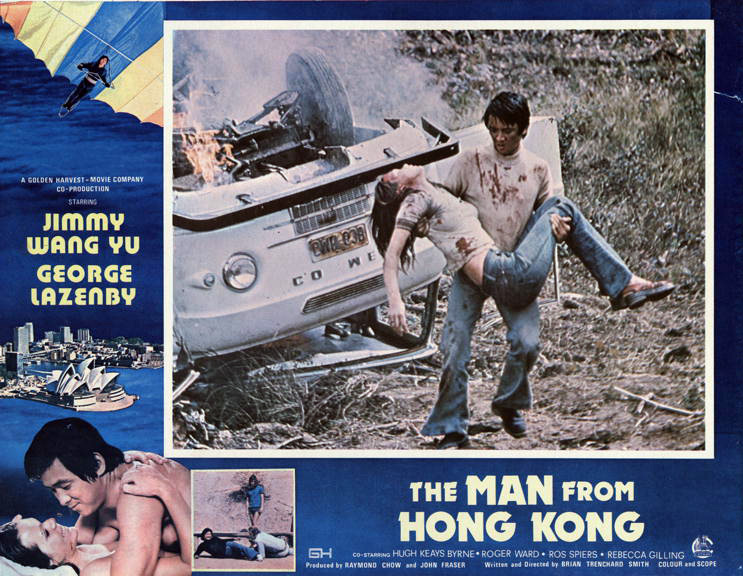

In contrast to the general 1970s mould of period dramas and ocker comedies was Brian Trenchard-Smith's high-energy The Man From Hong Kong (1975), an international co-production that cashed in on the highly successful martial arts action genre. The best sequence is a high-octane pursuit of an assassin by the lead character, Inspector Fang of the Hong Kong Special Branch, through the inner city streets of Darlinghurst, culminating in a ferocious kung fu fight in a packed Chinese restaurant. [media]The film is a playful, yet ultra-cool ballet of sex, violence and smart-arse dialogue. It was made at a time when Asian immigration was entering a new phase at the end of the Vietnam War, but the 'Asia' of the film is still very much an 'other' to the 'real' Australia. It would still be some time before an Asian presence became recognisably Sydney in Australian cinema.

Filming suburbia – the 1980s and 1990s

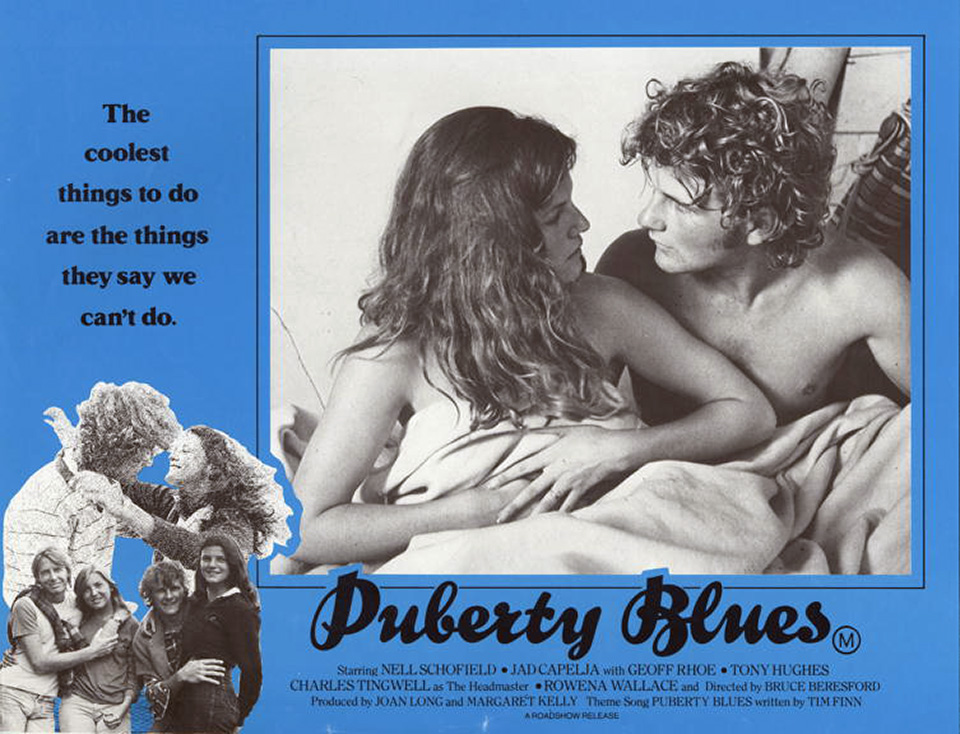

From the 1980s, urban films began to shift to centre stage, increasingly locating Sydney in the experience of suburbia. Women's stories were central to these new cinematic fictions, a trend directly related to the increasing proliferation of women in the industry. Jan Chapman points to the significant emergence of women in production from the 1970s onwards, women who became directors or producers 'because they just wanted to ensure that an idea became a film'. [14] It is not surprising then that the suburban domestic sphere became a prominent focus in films creatively controlled by women, given that women provided the bulk of the time and labour needed to ensure its upkeep. [15] Girlhood and growing up were dominant themes of some of the more remarkable films produced in this [media]period. Puberty Blues (1981) was an intimate and raw account of two girls growing up in the southern beach suburb of Cronulla, and their initiation into the world of surfing and groupie culture.

Sydney and suburbia have traditionally been linked in the Australian cultural and geographic imagination at least since the beginning of the twentieth century, although for most of that time, suburbia was not recognised as an appropriate topic for artistic treatment. The suburban films of the 1980s and 1990s began to challenge the dominant idea of the suburb as a dull, soulless and conformist place, instead transforming it into a fascinating playground of subversive characters and unusual events. Sweetie (Jane Campion, 1989) is a searing portrait of suburbia as seen through the figure of Kay, whose outer facade of normalcy is dangerously threatened by the arrival of her sister and nemesis, Sweetie, 'the epitome of everything that suburbia is traditionally perceived as not being.' [16]

Other attempts continued to recycle clichés of suburbia. In David Caesar's 1997 film Idiot Box, the two main characters are no-hoper blokes who drink beer, watch trashy television and dream up big schemes to escape the stultifying drabness of their lives. The theme of masculinity in the constraints of suburbia was explored in the popular surf documentary, Bra Boys (Sunny Abberton, 2007), which took $1.7 million at the box office, making it the highest-earning Australian feature documentary. A highly romantic account in the tradition of 'battler' narratives of Australian cinema, the film sentimentalised the history of Maroubra surfers and the suburb's disadvantaged youth's salvation in surfing while celebrating their anti-authoritarian activities.

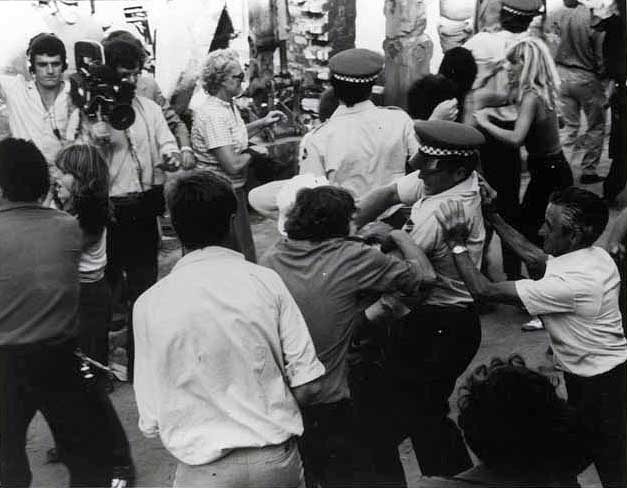

The unbridled growth and big development that gripped Sydney suburbs in the 1980s was uniquely addressed, and challenged, in the cinema. [media]Rarely have Sydney films exhibited the sort of dynamic political engagement as they did in 'redevelopment' dramas such as Heatwave (Phil Noyce, 1982), The Killing of Angel Street (Donald Crombie, 1981), the comedy Emoh Ruo (Denny Lawrence, 1985) and documentaries such as Waterloo (Tom Zubricki, 1981) and Rocking the Foundations (Pat Fiske, 1985). Key themes were the destruction of inner-city heritage, the propensity for ruthless and immoral developers to maximise profits over social and cultural needs, and the community resistance that sprang up around these sites of potential loss and gentrification. Heatwave is a steamy political thriller that pits an urban anarchist fighting for the rights of frightened inner city homeowners against sleazy developers. Caught in the middle is an architect trying to create 'Eden' – an enormous, uniquely designed multi-level environmental residence. The brightly-lit, humid feel of Heatwave manages to vividly evoke a Sydney summer, yet Noyce also manages to have this bleach-bright visual style generate the kind of dread and unease that is usually associated with the most darkly-lit thrillers and films noir. [17]

The film is based on the real-life disappearance of anti-real estate development crusader Juanita Nielson (who was never found). Twenty years later, Hell Has Harbour Views (Peter Duncan, 2005) reiterated the ongoing themes of greed and destruction in Sydney development.

Sydney has few city symphony documentaries that evoke the unique urban folklore and history of the city, but the hauntingly majestic Eternity (Lawrence Johnson, 1994) is one of the most evocative examples of memory and a disappearing city. This dramatised biography, told in a glorious black and white noir style that recreates 1930s Sydney, follows the night wanderings of Arthur Stace, a man who went about writing the word 'Eternity' in chalk copperplate on the footpaths of the city for 37 years until his death in 1967. Stace's ephemeral message became the city's typographical emblem, and the conscience of its residents caught up in the headlong rush of modern life. For Stace, the word 'Eternity' made 'people stop and think.' [18] In contemporary times however, the message has become tinged with a perverse kind of irony, in a pro-development city that continues to knock down and concrete over its past. [19]

Multicultural Sydney

In the 1990s, Australian cinema started to accommodate the image of a multicultural Australia, the policy embraced by successive Australian governments since the 1970s, with mixed success. [20] Strictly Ballroom (Baz Luhrmann, 1992) presents a highly romantic view of multiculturalism, in which the two main characters, Scott, a white man and Fran, a woman of Spanish background, challenge the dominant Anglo-Australian culture as represented by the Pan-Pacific Latin Dance Grand Prix, which they want to win. Set in the inner west, the film shows the Spanish family literally living at the end of the tracks, at the back of a shop in the slums. The film was hailed as demonstrating the triumph of multiculturalism by depicting the mingling of white and non-English speaking cultures through dance. However the way in which Spanish culture is presented exclusively through dance and music, while the realistic narrative happens in the space of white action occupied by the main character, Scott, also demonstrated a narrow view of multiculturalism, one that ensured white identity remained at the core of Australianness. [21]

In the twenty-first century, films defining Sydney were increasingly set in the western suburbs, but it was no longer the western suburbs of Aussie blokes, barbeques and cars (classically captured in Michael Thornhill's FJ Holden in 1977). A marginalised outer Sydney, emblematic of a social and cultural periphery, is inhabited by the characters and their stories.

Little Fish (Rowan Woods, 2005) is set mainly in Cabramatta, a suburb known to Sydneysiders as 'little Saigon' and famous for its image as a centre of Asian drug crime. The film subverts these racial stereotypes by making ex-addict Tracey (Cate Blanchett,) a white woman struggling to make something of her life, into the suburban hero of the film. She works in a Cabramatta video store and is trying to raise the money to open her own. The drug underworld she is reluctantly associated with is not defined by race. Her Anglo stepfather is a junkie and her Vietnamese ex-boyfriend a criminal in the making. The film does not comment on the ethnicity of the characters, instead inviting the audience to see them simply as Australians living on the edge. Khoa Doa's debut, Finished People (2003), also set in Cabramatta, is a more hellish portrait of three young people trapped in dead-end, hopeless lives, and gives a searing account of their existence. In this film we have a glimpse of that other Sydney, where poverty is very real and survival tough.

Lantana (2001) extends the theme of Sydney's diversity, and represents the city as free of the racial bias that has plagued the Australian story. Like the insidious weed from which the film takes its name, it is a complex study of human relationships, 'a pungent, prickly tangle.' [22] The film is set across distinctive Sydney locations that represent the different social and economic strata of the wider community, and by extension the nation. Recognisably Sydney in its landscape and cast (who range from gay, straight, ethnic, Indigenous, to professional, trade, married and single) it also maps a post-Pauline Hanson vision of Australia 'as a successful multicultural and tolerant community.' [23] In Lantana it is Sydney as 'ethnoscape' that becomes the face of the nation.

Indigenous Sydney

Mainstream filmmakers have not, historically, engaged with an Aboriginal presence in Sydney in any meaningful way, reflecting an old assumption that 'real' Aboriginal people do not 'belong' in the city, but are connected to the land. There are few films that show Aborigines in Sydney (Peter Weir's The Last Wave, 1977, is a very strange example) and fewer still by Indigenous filmmakers that engage with the city at a fictional level.

At the turn of the twentieth century, films that featured Aboriginal people were ethnographic and paternalistic. John Gavin's Assigned to His Wife (1911), set in the early days of the colony, features an Aboriginal man who saves the life of an innocent deportee and hence establishes the 'good tracker' cliché. However later in the century, some filmmakers started to challenge the culture of silence surrounding Aboriginal Sydney.

Internationally acclaimed video artist Tracey Moffatt's first film, Nice Coloured Girls (1987), is one example. [24] It features three dynamic Aboriginal women who cruise Kings Cross at night, pick up a 'Captain' and seduce him into spending all his money on buying them drinks. When the Captain is drunk they steal his wallet and escape joyously into the city streets. This story is juxtaposed against the soundscape of colonist Lieutenant William Bradley reading from his diary, and positions this short film as a reappraisal of colonial history and gender relations.

In Ivan Sen's lyrical Beneath Clouds (2002), two Indigenous teenagers undertake a journey to Sydney to escape the predictability and oppressions of the bush. Here the city symbolises escape, change and new opportunities to bring their dreams to reality. In the final scene of the film, the teenagers arrive at an outer suburban train station after narrowly escaping from the police. This is an ambivalent ending: life for them will be difficult but there is just a glimmer of hope that they will be able to start their life afresh as the silver haze of the city beckons in the distance.

Hollywood backlot?

Sydney continues to market itself as a cosmopolitan centre of international exchange, in which making movies has a starring role. Fox Studios became the Sydney home for runaway productions from the US, such as The Matrix franchise and Mission Impossible 2 , integrating Sydney locations into international sci-fi blockbusters. The Sydney-based visual effects team Animal Logic has also revitalised Sydney's international film reputation. Babe: Pig in the City (George Miller, 1998) was an outstanding example of their digital wizardry. Set in a fictional metropolis, Babe created a postmodern fantasy land of world architecture that combined the Sydney skyline with global icons such as Red Square and the Golden Gate Bridge. Similarly, the enormous popularity of Pixar's animated Finding Nemo (Andrew Stanton, 2003), a large part of which was set in Sydney Harbour, is said to have led to a massive jump in tourism to Australia. [25]

Still going to the show

Since the late 1980s independent arthouse venues that were an integral part of the inner city scene (including the Mandolin, Valhalla, Lanfranchi's and for a short time, the Chauvel) have disappeared, unable to survive in the new era of multiplex cinemas. This has been a major loss of independent arthouse cinema exhibition, and for some, signified the victory of a commercially driven, Hollywood dominance. In that sense, it would appear that Sydney has truly become the 'Emerald City'. However, [media]the importance of foreign-language film screenings and festivals to Sydney audiences also demonstrates the diversity of the everyday cultural experience of watching movies. It complicates the common assumption that Australia is a homogeneous viewing nation, universally tuned to American content and passively 'Americanised' in the process. [26]

During the 1970s and 1980s, a central feature of growing up for the authors meant visiting the strip of multiplex cinemas along George Street in the City centre, a meeting place for the hordes of raucous teenagers who made the trip each weekend from the suburbs. The spread of the multiplexes to the suburbs has meant the loss of many small, family-run cinemas that were an important part of the identities of their local communities. Only a few, such as the Roseville Cinema, the Randwick Ritz and the Cremorne Orpheum, remain. However the suburban cinema has remained a principal site of leisure and entertainment for local audiences. Going to 'the flicks' is still one of Sydney's great pleasures.

New films set in and around Sydney are drawing on its complexities to transform ideas of the city and its inhabitants in the cultural imagination. Sydney has become a city of many faces, both old and new – a criminal city, an amoral city, a city of dreams, a 'postmodern, multicultural metropolis' [27], and sometimes, all of these things at once. There is no such thing as one Sydney, and for its audiences and the filmmakers who use it, it is this mix of unpredictability and possibility that will no doubt continue to make the city a rich source for the stories of cinema.

Notes

[1] Graham Shirley, 'Australian Cinema: 1896 to the renaissance', in Scott Murray (ed), Australian Cinema, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p 5

[2] Diane Collins, ''More than just entertainment' (1914–1928)', in Ina Bertrand (ed), Cinema in Australia: A documentary history, New South Wales University Press, Kensington, 1989, p 69; Diane Collins, 'Shopfronts and picture showmen: film exhibition to the 1920s', in James Sabine (ed), A Century of Australian Cinema, Mandarin Australia, Victoria, 1995, p 36

[3] Graham Shirley, 'Australian Cinema: 1896 to the renaissance', in Scott Murray (ed), Australian Cinema, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p 10

[4] Jill Julius Matthews, Dance Hall and Picture Palace: Sydney's Romance With Modernity, Currency Press, Sydney, 2005, pp 57–8

[5] Graham Shirley, 'Australian Cinema: 1896 to the renaissance', in Scott Murray (ed), Australian Cinema, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p 10

[6] Megan McCurchy, 'The Documentary', in Scott Murray (ed), Australian Cinema, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p 185

[7] Megan McCurchy, 'The Documentary', in Scott Murray (ed), Australian Cinema, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p 185

[8] Lennart Jacobsen, 'The Polysemous Coathanger: The Sydney Harbour Bridge in Feature Film, 1930–1982', Senses of Cinema, 40, July 2006 http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/06/40/sydney-harbour-bridge.ht

[9] Rosaleen Smyth, 'From the empire's 'Second Greatest White City' to multicultural metropolis: the marketing of Sydney on film in the 20th century', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 18 no 2 (June 1998) p 237 (26)

[10] Adrian Martin, 'The Short Film', in Scott Murray (ed), Australian Cinema, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1994, pp 201–10

[11] V Canby, 'Caddie: an Australian Woman on Her Own', New York Times Review, 8 February 1981

[12] Tom O'Regan, 'Cinema Oz: The Ocker Films', in A Moran and T O'Regan (eds), The Australian Screen Penguin Books, Ringwood, 1989, p 82

[13] Ian Craven, 'Historicizing transition in Australian cinema: the moment of Emerald City', Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol 1 no 1, 2007, p 32

[14] Jan Chapman, 'Some Significant Women in Australian Film – A Celebration and a Cautionary Tale', Senses of Cinema, no 22, Sept–Oct 2002: http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/02/22/chapman.html

[15] Catherine Simpson, 'Suburban Subversions: Women's Negotiation of Suburban Space in Australian Cinema', Metro, no 118, 1999, p 24

[16] Catherine Simpson, 'Suburban Subversions: Women's Negotiation of Suburban Space in Australian Cinema', Metro, no 118, 1999, p 26

[17] Nick Prescott, 'Heatwave (DVD)', ABC Adelaide, http://www.abc.net.au/adelaide/stories/s2003946.htm

[18] http://australianscreen.com.au/titles/eternity/clip2/

[19] Sharon Verghis, 'One Word Sermon We Can't Forget', Sydney Morning Herald, 19 January 2005, http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2005/01/18/1105810905250.html

[20] James Bennett, 'Head On: multicultural representations of Australian identity in 1990s national cinema', Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol 1 no 1, 2007, p 64

[21] James Bennett, 'Head On: multicultural representations of Australian identity in 1990s national cinema', Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol 1 no 1, 2007, p 71

[22] Felicity Collins, 'God Bless America (and Thank God for Australia)', Metro Magazine, 131/132, p 20

[23] Kirsty Duncanson, Catriona Elder and Murray Pratt, 'Entanglement and the Modern Australian Rhythm Method: Lantana's Lessons in Policing Sexuality and Gender', Portal, vol 1 no 1, 2004, p 6

[24] Lisa French, 'An Analysis of Nice Coloured Girls (Tracey Moffat)', Senses of Cinema, 5, April 2000, http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/00/5/nice.html

[25] P Mitchell, 'Nemo-led recovery hope', The Age, 3 June 2003 http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2003/06/03/1054406187273.html

[26] Kate Bowles, Richard Maltby, Deb Verhoeven and Mike Walsh, 'More Than Ballyhoo? The importance of understanding film consumption in Australia', Metro, no 152, April 2007, p 97

[27] Richard Waterhouse, 'Culture and Customs', Sydney Journal, vol 1 no 1, March 2008, http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/sydney_journal/index

.