The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Governor Phillip and the Eora

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Governor Phillip and the Eora: governing race relations in the colony of New South Wales

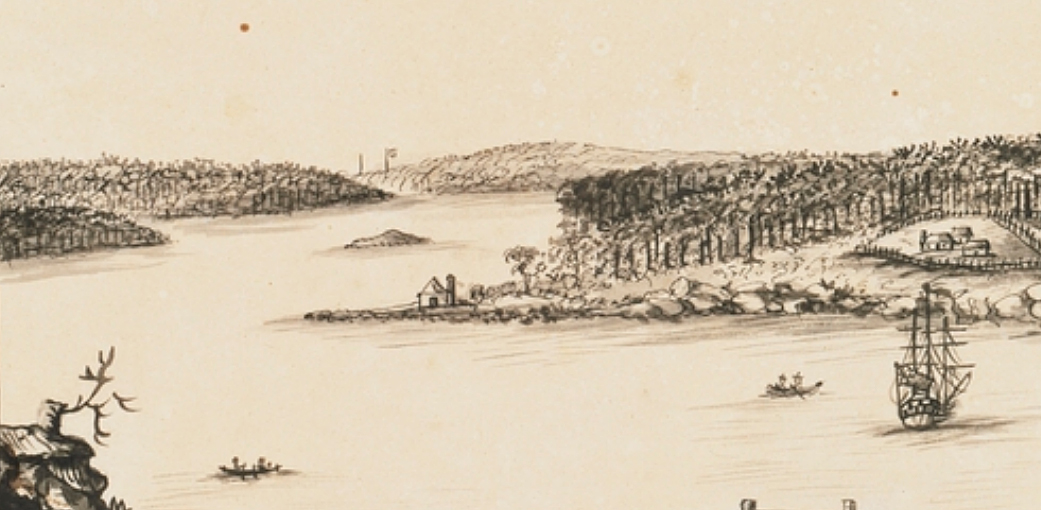

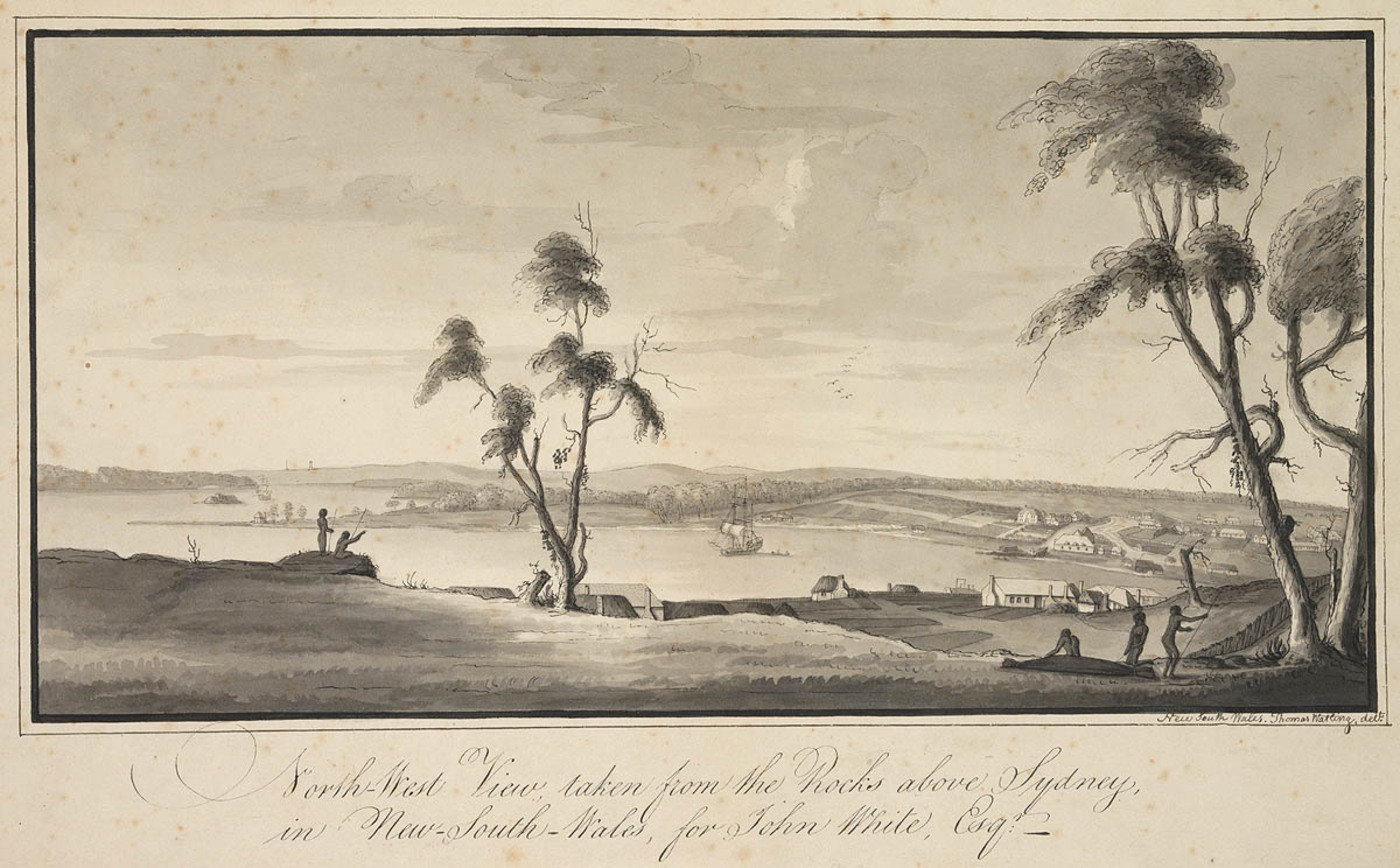

[media]In the Botanic Gardens stands a grand monument to Arthur Phillip, the first governor of New South Wales. Unvieled in 1897 for the Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, the elaborate fountain expresses late nineteenth century ideas about society and race. Phillip stands majestically at the top, while the Aboriginal people, depicted in bas relief panels, are right at the bottom. But this is not how Phillip himself acted towards Aboriginal people. In his own lifetime, he approached on the same ground, unarmed and open handed. He invited them into Sydney, built a house for them, shared meals with them at his own table.[1]

[media]What was Governor Arthur Phillip's relationship with the Eora[2], and other Aboriginal people of the Sydney region? This, of course, is a loaded question that has been explored by historians and anthropologists for some decades now. The debate has moved like a pendulum between mutually exclusive conclusions: Phillip as a good guy or a bad guy; race relations in the early colony were peaceful or violent. [3] To make this question still more complex, Phillip's policies, actions and responses have tended to be seen as a proxy for the Europeans in Australia as whole, just as his friend, the Wangal warrior Woolarawarre Bennelong’s allegedly tragic life has for so long personified the fate of Aboriginal people since 1788.[4] Yet we know the past, like the present, is rarely so simple.

[media]Since the 1980s the power of historical imagination – mostly inspired by anthropology and ethnographic history – has reshaped the ways historians think and write about the past. Historical imagination is not about inventing the past, it is about recreating, as fully as possible, the 'past's own present’. It is about re-imagining the human situations, the dilemmas and decisions, and what it's like not knowing what is going to happen.[5]

To fully imagine those early years, to glimpse what was happening, and why, we must explore them through the twin lenses of British and Eora perspectives and experiences. This allows a nuanced and complex view, and it banishes once and for all the notion that there can be only one 'right' story.

Intentions and expectations

Phillip's official orders with regard to Aboriginal people were to 'conciliate their affections', to 'live in amity and kindness with them', and to punish anyone who should 'wantonly destroy them, or give them any unnecessary interruption in the exercise of their several occupations'.[6] Historian Kate Fullagar points out that these orders were not unique to Phillip or New South Wales, but standard orders for the time – the aim being to cultivate Indigenous people so they would provide information and co-operation.[7] But Phillip himself wrote that he hoped to 'give them a High Opinion of their New Guests' through kindness and gifts.[8]

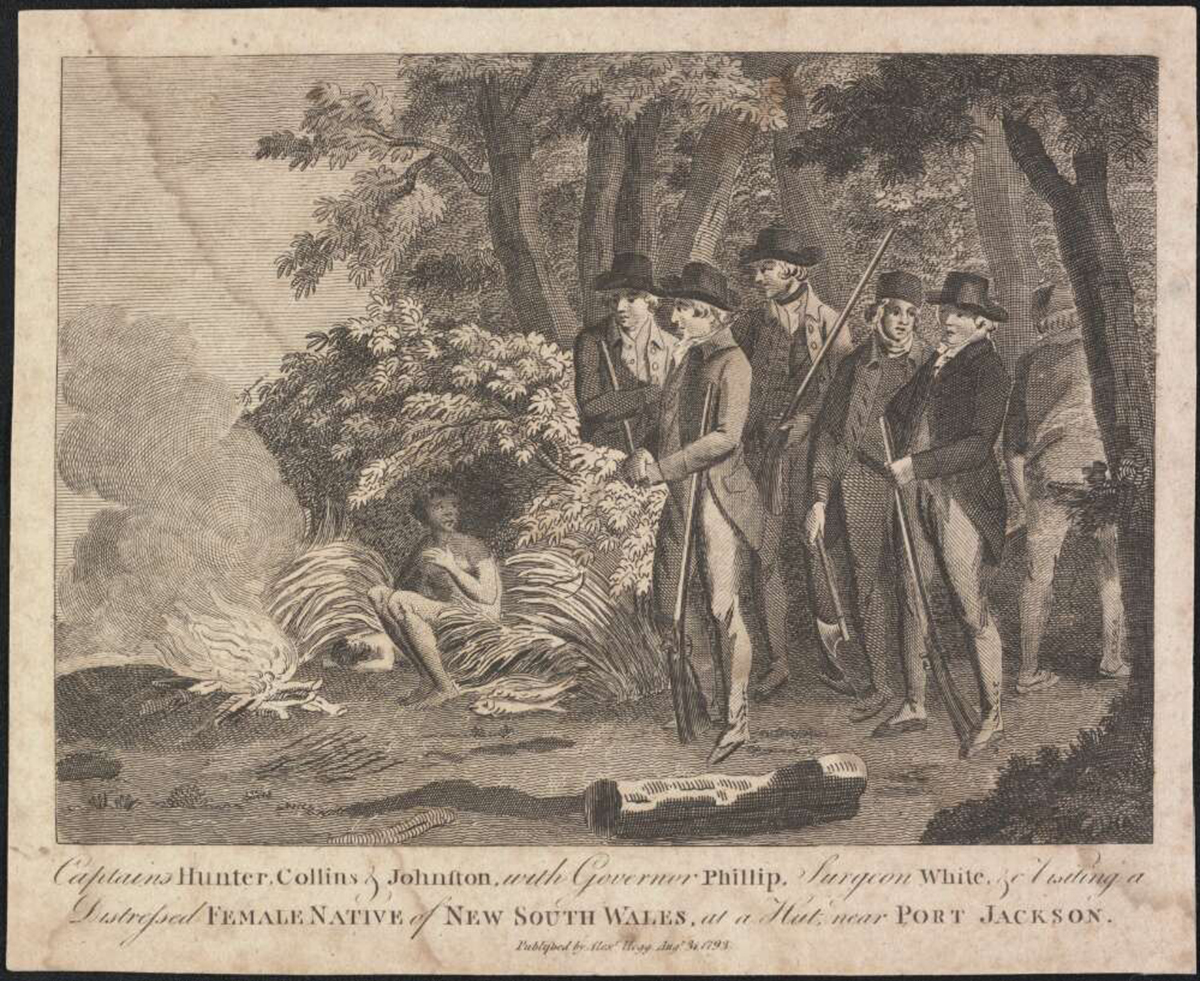

[media]I agree with Inga Clendinnen and others that Phillip and the officers were genuinely committed to establishing and maintaining friendly and peaceful relations.[9] Phillip initially thought there would be no problem avoiding disputes with Aboriginal people. In fact, he and the officers hungered for friendship. The early meetings in Botany Bay and Port Jackson were often marked by friendliness, curiosity, gift giving and dancing together on the beaches. This is so entirely different from earlier violent and murderous encounters between Europeans and Indigenous people. It is also very different from the frontier violence that dominated pastoral expansion in Australia well into the twentieth century. In that sense it was enlightened and humane.

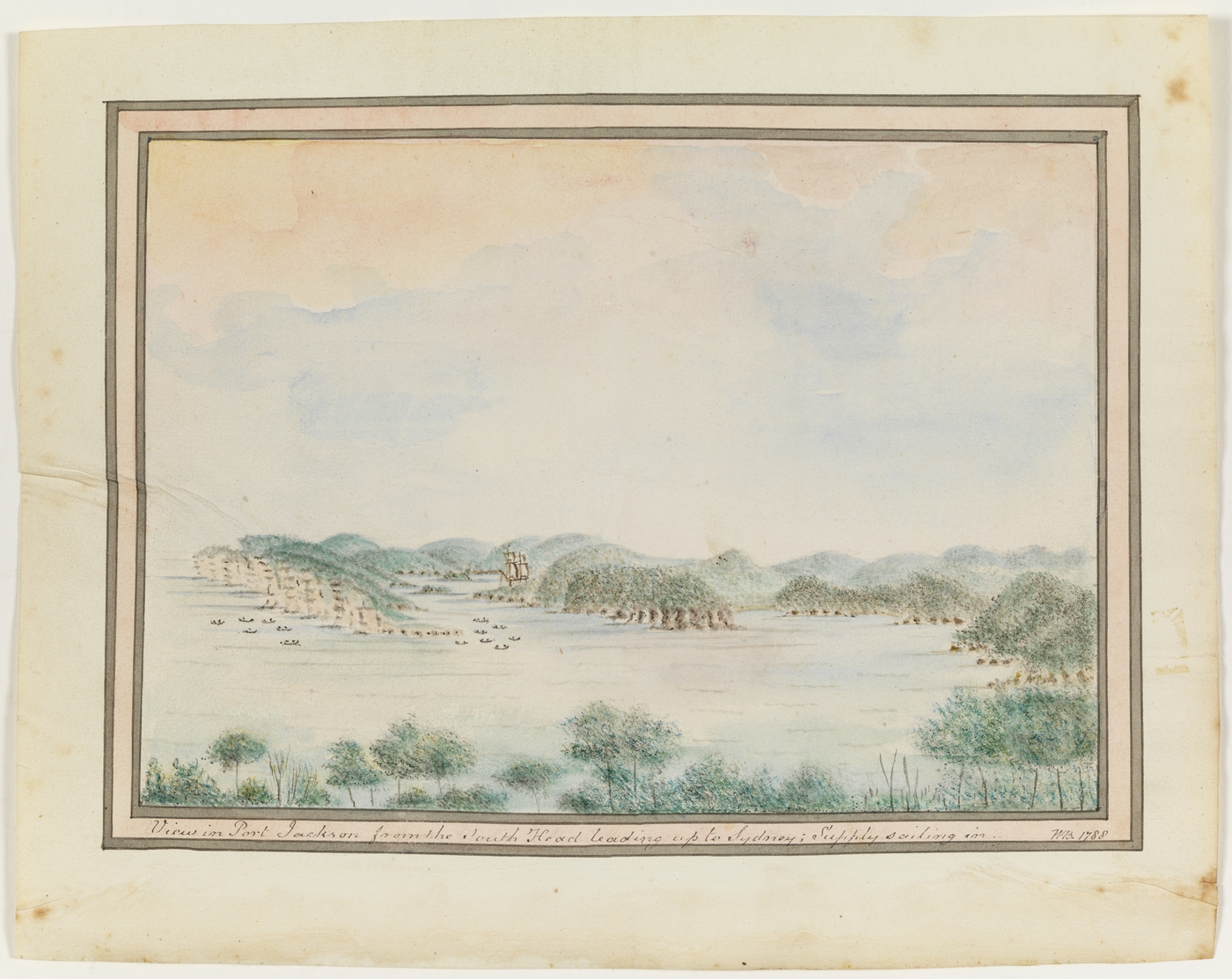

[media]The perspective of the broader Aboriginal world adds something useful here: after all, the arrival of the First Fleet and the setting up of the small camp in Sydney Cove is momentous only in retrospect: it marked the origins of a great city. But at the time it was just a tiny pinprick on the edge of a vast and ancient Aboriginal continent – it made barely a ripple at first. From this perspective, the idea that Phillip's first footfall on the beach in Botany Bay brought instant death and corruption across the entire continent is Eurocentric nonsense. Aboriginal people did not drop dead or lose their culture the moment they saw a white person.[10]

But the Eora of the Sydney region did have to cope with this sudden influx of around 1,000 strangers descending on their waterways and lands. There were no doubt oral traditions and songs about those earlier strangers and the muri nowie, Cook's big canoe, which had stayed in Botany Bay for a few days in 1770 and then gone away again. This time the number of muri nowie, and the number of these strangers in their coloured skins, was probably alarming. But surely, they too would leave again, like the last lot?[11]

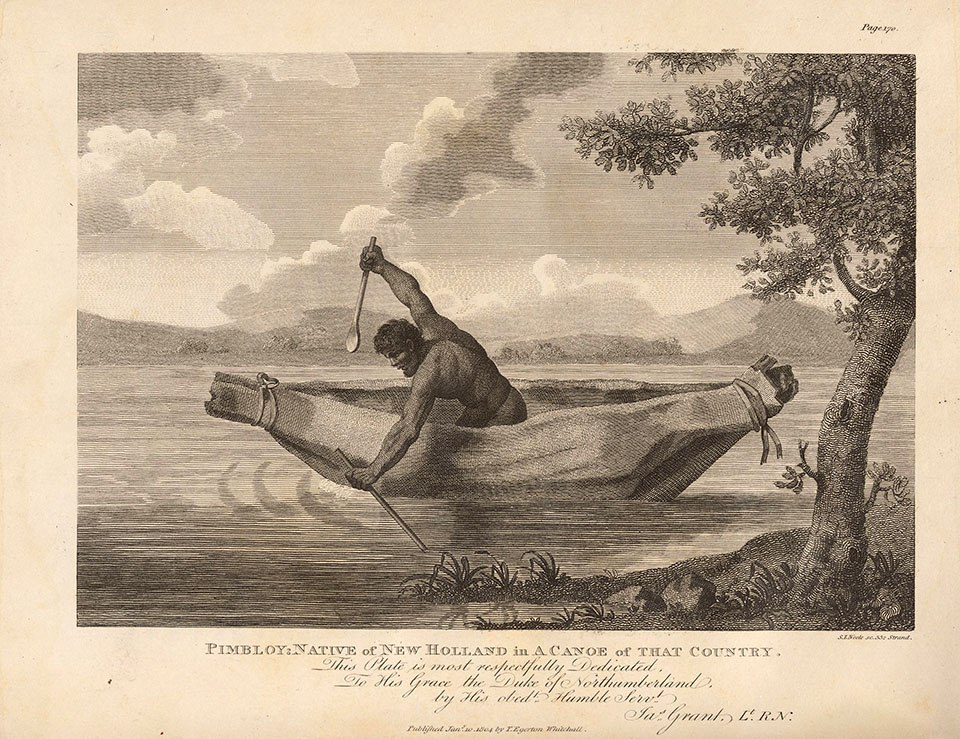

[media]The Eora already had a name for strangers – Berewalgal – and they had protocols for them too. Women and children stayed well away while the warriors stood on beaches or clifftops and shouted unmistakable warnings to the newcomers. At Kai'ymay, later Manly Cove, in north harbour, they waded out to meet the longboat, strong, proud, purposeful and curious.[12] At those initial meetings, the first Eora priority appears to have been to establish the strangers' sex – men, after all, dealt with men. The Berewalgal had no beards and they did not appear to have male sex organs. Once he grasped the question, Phillip instructed a sailor to drop his pants at one meeting – in response a great shout went up from the Eora warriors. They are men! The next priority was to discover their intentions. What did the strangers want? Food? Water? Access to hunting grounds? Or, given they didn't appear to have any women with them, and continually asked to meet Eora women, perhaps they wanted wives? This would take some serious negotiation, since women were the food providers, they bound clans together, and they would bind the strangers into local families through reciprocal rights and obligations.[13]

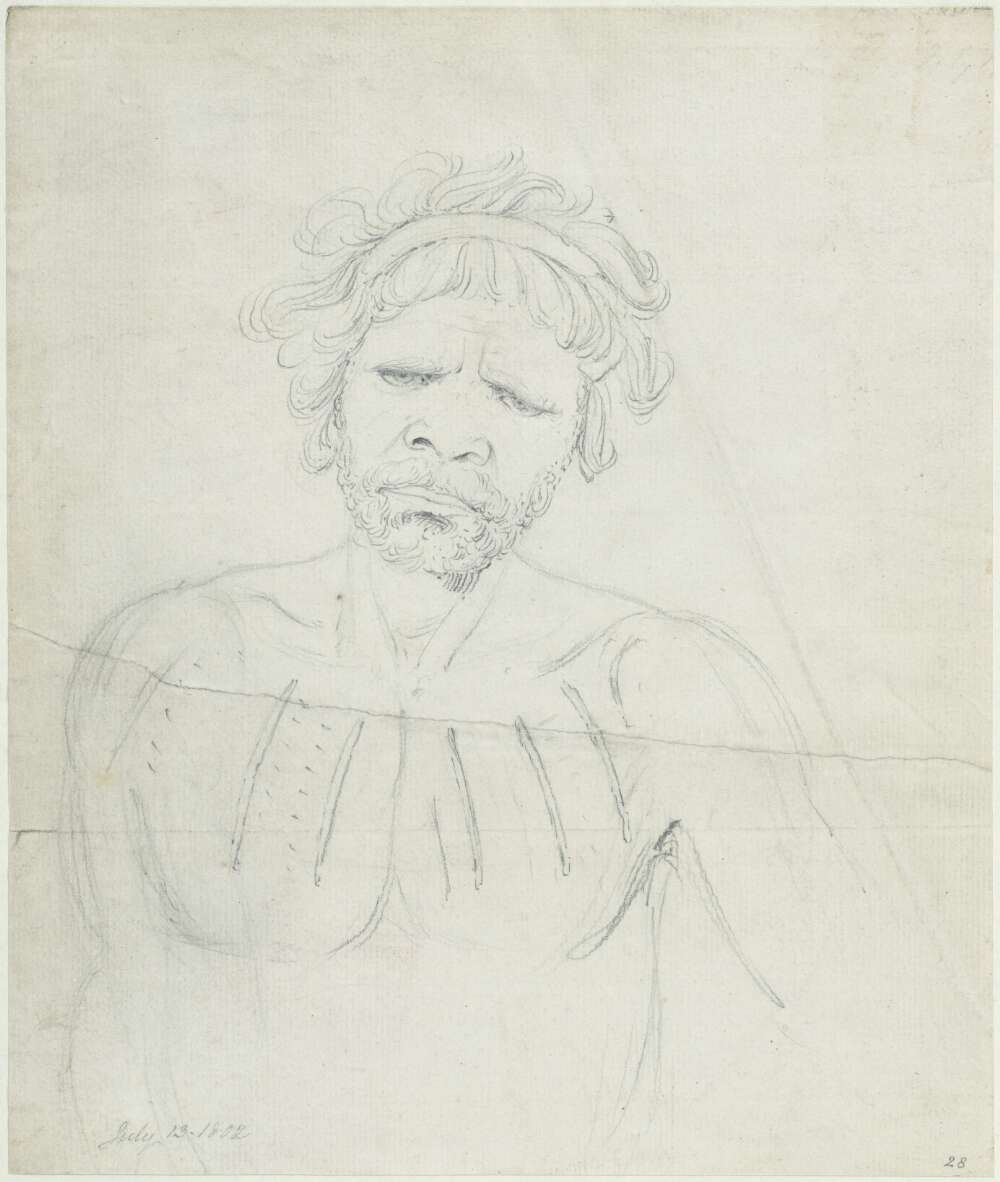

[media]Meanwhile, back on the British side, those intentions of amity and peace were also contingent on some deeply flawed information. Phillip and the officers only had James Cook and Joseph Banks' accounts to go on, and they had portrayed the Eora as very few, weak, and cowardly – in other words, a rather pathetic, simple, childlike people whom it would be easy to treat kindly. But Cook and Banks were wrong – they had forgotten or downplayed the show of strength and daring they themselves encountered from Eora warriors in 1770.[14] The Eora were nothing like their description – their’s was, in Clendinnen's words, a 'tough warrior culture'.[15] They were strong, their spears accurate and deadly and their Law centred on retributive justice – righting wrongs through payback. No wonder Phillip was taken aback to see so many armed men shouting belligerently from the cliff tops, to see those twenty warriors of impressive physique wading out to meet the boat at Kai'ymay. This is the real meaning of his name for the Cove there: Manly. It was an expression British admiration for their 'manly' qualities. I believe that a key reason Phillip chose Sydney Cove (Warrane) for the settlement was not only the bright stream of fresh water there, but the fact that it was the one place in Port Jackson where there were no warriors, shouting and waving spears.[16]

This realisation on Phillip's part also reinforces something that Clendinnen tended to de-emphasise in her version of the first encounters: guns. Phillip and the officers began their relationship with the Eora through gift-giving, hilarity and dancing but also by showing them what their guns could do. There is no getting around this. Watkin Tench wrote bluntly: 'Our first object was to win their affections, and our next was to convince them of the superiority we possessed: for without the latter, the former we knew would be of little importance'. So they fired the muskets over the heads of the Eora and shot musket balls right through their wooden shields.[17]

[media]Eora communications were lightning fast, so word spread quickly about the strangers' dangerous weapons, their geerubber or fire sticks. They even called the strangers Geerubber: guns were clearly their most defining characteristic. The muskets were also associated with the soldiers' red coats – the sight of which would instantly make the Eora melt away into the bush. Guns made the first meetings possible but they also stopped the process of communication and friendship in its tracks, and the officers knew it.[18]

Phillip did forbid anyone from shooting or otherwise harming Eora. But by anyone he meant convicts. He had them severely punished for doing so and for stealing from Eora. But this did not mean that officers and other military did not shoot at Aboriginal people – they did, usually with small shot, usually because warriors were throwing spears and stones at them. The first fatality may have occurred in September 1789 when Henry Hacking shot into a group while out hunting on the North Shore.[19]

After the early meetings, dancing and musket demonstrations, the Eora for the main part avoided the Camp in Warrane, Sydney Cove, for at least the first year.[20] Perhaps they expected the strangers to pack up, go away and leave them in peace, as Cook had done. When this hope faded, the Eora tried to keep the Berewalgal quarantined in their country, Warrane, Sydney Cove. They attacked unarmed convicts and fishermen, and occasionally even armed officers and soldiers, whenever they trespassed on lands away from Warrane.[21] Eventually Phillip realised what they were doing. In response, he sent two armed parties out to Botany Bay and other places in October 1788 to show them, as Collins wrote, 'that their late acts of violence would neither intimidate nor prevent us from moving beyond the settlement whenever occasion required'.[22] From Phillip's perspective this was essential: the whole territory had been officially claimed and was now British. The town depended on the food and building resources of the wider region and so he was determined to demonstrate that they would go where they wished.

Part of Phillip's early plan for peaceful co-habitation had been to persuade some Eora – preferably a family – to come and live in the town with the British. Not only could the British then learn about the Eora, their language, beliefs and customs – the Eora might be convinced of the newcomers' friendly and peaceful intentions. They could also be introduced to the wonders and comforts of the British way of life and then act as envoys, spreading the message of goodwill and civilisation among their own people.[23]

[media]Again, this plan was underpinned by some profound cultural assumptions. While they were very interested in the Eora, Phillip and the officers seem to have had little inkling that they already had their own complex social and cultural systems and were in no need of British ones. The idea that the Eora would or could abruptly drop their entire culture and way of life for a British one seems bizarre to us. But that is what the British assumed would happen. When it didn't, they were confused. How could anyone not want to be British?

The Eora were also theoretically already British subjects because they were not considered to be the sovereign occupants or owners of the land. Thus they were – supposedly – subject to British justice – also considered a great gift.[24] But the Eora had their own legal system, and they were often repelled by what they saw of British justice. When forced to watch floggings, for example, they were horrified. In their own system of justice, the guilty were not bound and helpless but could defend themselves against the spears by parrying with shields.[25]

Kidnapping and payback

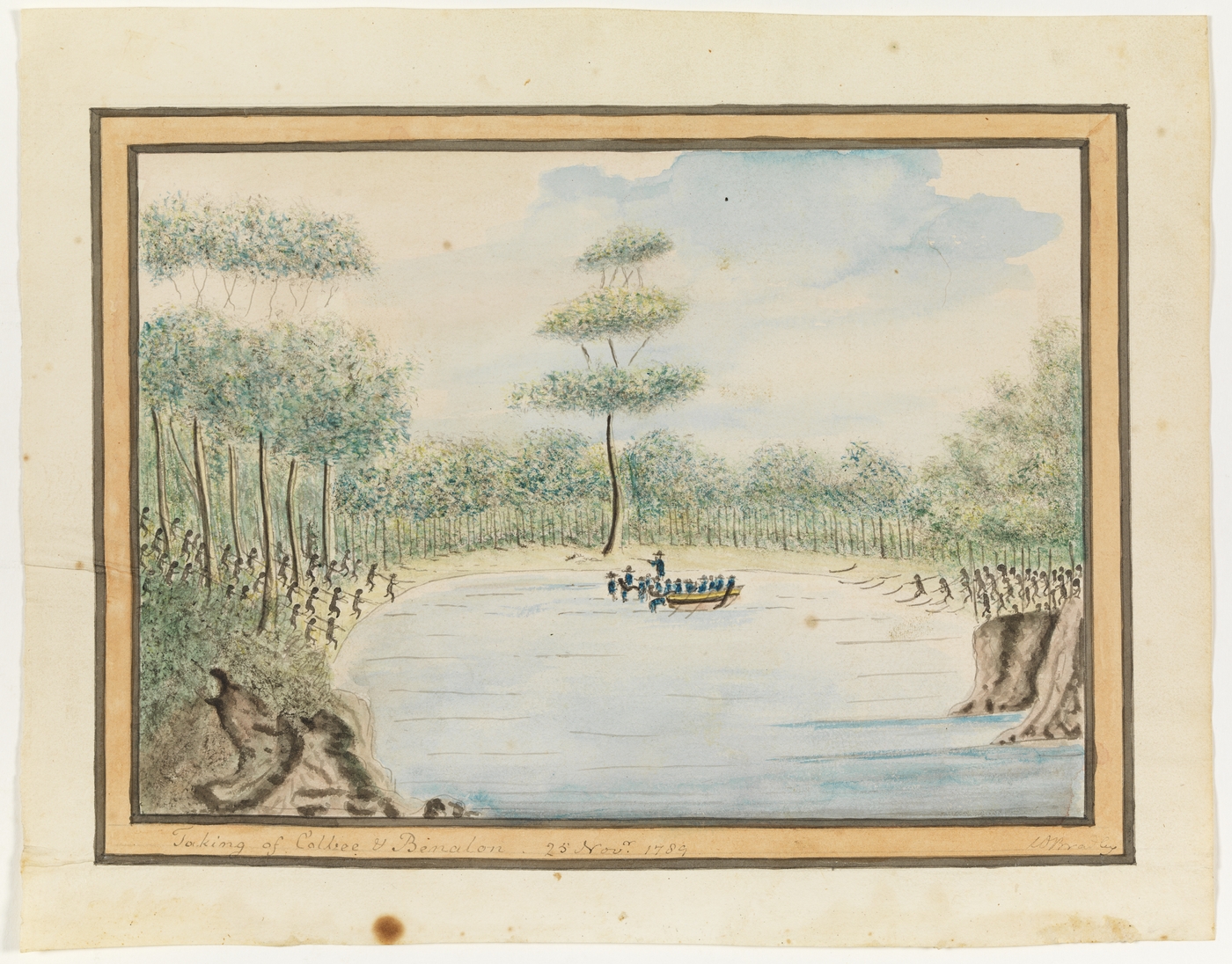

[media]By the end of that first year, 1788, Phillip still had not persuaded anyone to 'come in' to Sydney and the situation was getting increasingly urgent. He still had no idea of Eora numbers or their intentions towards the settlers and the warriors had attacked and killed a number of convicts. Phillip decided on a more ruthless strategy: kidnapping. The kidnapping was violent and distressing and the man they took from Manly Cove was the gentle, homesick Arabanoo. After he died of smallpox, caught during the smallpox epidemic that decimated the Eora from April 1789, the violent skirmishes again escalated. Phillip sent the boats out once more to Manly Cove, and two more warriors were taken – Coleby and Woolarwarree Bennelong. They were tied up and held prisoner and under guard at Government House. Coleby soon escaped but the extroverted, charismatic Bennelong remained. Bennelong seemed to be the breakthrough Phillip and the officers were hoping for. Eventually Bennelong and Phillip developed a kind of friendship, walking out together companionably. Bennelong called Phillip Beanna, father or elder, and Phillip called Bennelong Dooroow, or son. Phillip seems to have thought of these names in father-son terms: he was the wise father, teaching and guiding the son.

[media]But what did Bennelong make of all this? As a warrior enmeshed in the complex, post-smallpox, inter-tribal politics of the region, he seemed to be learning all he could about the Berewalgal, their allegiances, their fighting power, their great reserves of food, and he was doing all he could to please them and make them his allies. In April 1790 the fetter was struck from his leg, and Bennelong stripped off his clothes and escaped. Phillip and the officers were bereft. Yet another cross-cultural experiment seemed to have failed.[26]

In Aboriginal Law, justice must be done, and the world righted, through payback. If the perpetrator could not stand trial, then someone of his or her family or clan would have to stand for them. Guilt was transferrable to family and clan. Several historians, including William Stanner, Inga Clendinnen and Keith Vincent Smith, believe that before any further relations could occur, Phillip had to stand trial and be punished according to Aboriginal Law for his crimes and the crimes of his people.

[media]One day, four months after Bennelong left Sydney, Phillip was invited to a great whale feast at Manly Cove. He and some of the officers hurried over in a boat and were greeted there by Bennelong. Relations were friendly and jovial, just like old times. But Phillip suddenly found himself surrounded by warriors and was then swiftly speared in the shoulder. There was panic as the officers and men rushed him into the boat and back to Sydney. But the spear was not a death spear and the wound was not fatal. Phillip soon recovered. Most importantly, he refused to retaliate, suggesting that he sensed the purpose of the spearing.[27]

[media]Phillip's spearing was followed by a breakthrough. The Eora began inviting the Berewalgal to meetings, friendships were re-established, and there was once more dancing, feasting and fun on the shorelines. Finally, after much negotiation, Bennelong was persuaded to 'come in' to Sydney, along with his family and friends. Bennelong was like a returning king: everyone in the town came out to see him as he and his people marched up from the wharf to Government House. He asked for a British style gunyah (house) to be built for him on Tubowgully (Bennelong Point) and Phillip obliged. For Bennelong and his people, this move was very likely seen as taking possession of this country at Warrane.[28]

This was one of the happiest days for many of the early officer chroniclers – they were genuinely delighted and relieved, because they believed that the violence was now at an end, and the two groups were now friends, who would live in amity.[29] It is deeply poignant to read those words now, knowing what happened in the decades that followed.

Law

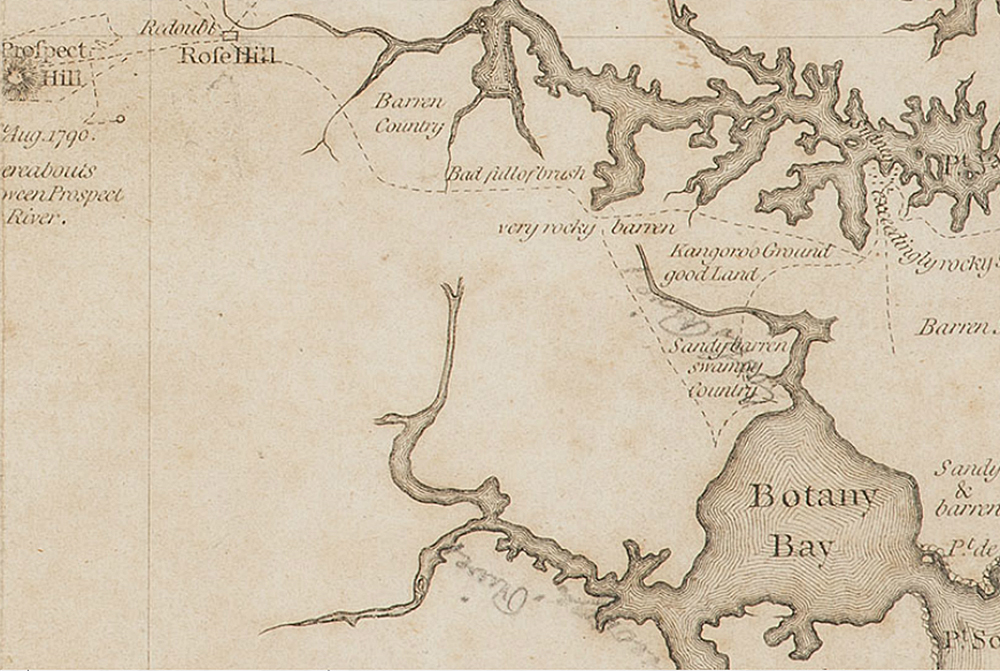

[media]Phillip and the officers expected the Eora would now obey British law, not only in town but throughout the whole colony. They were seemingly still unaware that payback was Aboriginal Law and had to be upheld. Because the Eora continued to extend their Law to white colonists, conflict was inevitable.[30] In December 1790, the warrior Pemulwuy fatally speared Phillip's own gamekeeper, John McIntyre. McIntyre had earlier wounded a warrior and probably his spearing was payback. Many believed he had committed other serious crimes as well.[31] When Phillip found out that McIntyre had been unarmed and that he had been approaching Pemulwuy in a friendly manner, he decided it was time to act. The Eora needed to be taught a terrifying lesson, once and for all. [media]He ordered a party of 50 soldiers, led by Lieutenant Watkin Tench, to march to the head of Botany Bay, capture two Eora men, and march them back to Sydney for public execution. As well, he wanted ten more men beheaded, and their heads brought back to town. Friendly relations of all kinds were suspended: 'all communication, even with those natives with whom we were in the habit of intercourse is to be avoided'.[32] Tench suggested that the number of intended victims be reduced to six: they would be arrested and brought back to Sydney where some would be force to witness the execution of their countrymen, then set free. Phillip agreed but insisted that those not executed would be exiled to the small colony at Norfolk Island. He added that if warriors could not be arrested, they were to be summarily shot. The party was provided with hatchets for the chopping and bags to carry the heads, so presumably the beheading order was still in force.[33]

The party duly marched out from Sydney towards the southwest of Botany Bay – probably the area around present day Lansdowne and up to the tidal limits of the Georges River around Liverpool. Despite marching around the area all day, Tench wrote that they failed to find a single person. So they headed east towards the 'south west arm' of Botany Bay – Georges River. But their guides lost their way and they found themselves on the 'sea shore…about midway between the two arms' (that is, the Georges and Cooks Rivers) where they saw and tried to surround five Aboriginal people. But these people escaped, disappearing into the bush. Tench then marched the party to a known 'village' of huts on the 'nearest point of the north arm' – most likely on the south shore of Cooks River near its mouth (present day Kyeemagh). But here again the Aboriginal people swiftly paddled to safety to 'the opposite shore'. The mosquito-bitten party returned to Sydney, exhausted and frustrated.[34]

But Phillip was determined. He sent Tench and the soldiers out again. The second expedition, on December 22, left Sydney at sunset, in the hope they would surprise, arrest or kill people while asleep in their camps (by now the British knew that the Eora were heavy sleepers). The party forded two rivers before almost drowning in quicksand in a creek. When they arrived back at the village on Cooks River, it was deserted and had been for some days. A final attempt to locate, arrest or shoot warriors was made at 1.30 in the morning – again without success. Tench says he gave up four hours later and marched the soldiers back to Sydney.[35] Oddly, he failed to specify where this last attempt was made, but John Easty, one of the privates on the expedition, noted it in his journal:

[we] Started again att 3 oclock and went to Botany Bay and halted on the North Shore untill 2 on the Morning of the 24 when we went Down the Beach for abought 3 miles whaare we Saw Sevaral of the natives by thier fires and then and Marched Back to the Place from whence we Started and halted till 7 oclock when we returned to Sidney by 9 that morning after a most teadious march as Ever men went in the time.[36]

[media]Tench's party thus appears to have combed the whole area from Cooks River to Prospect Creek and the Georges River. Contrary to Tench's account, Private Easty says they finally found a group of Aboriginal people on the beach at Botany Bay – but then returned to Sydney.[37]

This 'headhunt' has become contentious in recent years. Those who admire Phillip find it difficult to accept that the enlightened, fair-minded and humane governor gave such gruesome orders and intended the arrest and execution of innocent people rather than just the guilty man. Inga Clendinnen, taking cues from Tench's perhaps unintentionally comic account, interprets the whole incident as an elaborate piece of farcical theatre performed for the benefit of the unruly and resentful convicts. Wise Phillip knew the party would not find anyone, she says, let alone behead them. He never intended anyone to get hurt, and just to make sure, he put the sympathetic Watkin Tench in charge.[38]

Was the 'head hunt' simply a grand show with no serious intent to harm? As we have seen, guns and the threat of violence were fundamental to the settlement project from the start. Once Bennelong and his people agreed to 'come in' to Sydney in late 1790, Phillip believed he had an agreement that the attacks and killings of unarmed convicts would stop because he thought he had finally brokered peaceful relations via leaders Bennelong and Coleby. When McIntyre was speared and killed, Phillips saw it not only as a final betrayal of all his kindness and patience, but also as a breaking of the 'agreement' for peaceful relations.

The fact that Phillip sent out two expeditions, rather than just one, is significant. Had this been a piece of theatre for the benefit of the convicts and others, one would surely have sufficed. Two – the second starting out at dusk to catch people while they slept – signifies the seriousness of Phillip's intent. So does the fact that Tench scoured the country from the head of Botany Bay to the coast – thus while the intended targets may originally been Pemulwuy's Bidgigal clan, other groups were soon hunted as well. Lieutenant William Dawes, who was also sympathetic to the Eora, at first refused to take part but was then persuaded to go. Afterwards he was disgusted with the whole expedition and would not retract this opinion. He was forced to leave the colony as a result, even though he wanted to stay.[39] It is unlikely Dawes would have felt so strongly if the expeditions were make-believe.

It is also possible that someone was wounded. Tench was not entirely truthful in his account – Collins reported that the soldiers on the expedition did in fact shoot at Aboriginal people, though he insisted that they failed to hit anyone.[40] Tench also omitted the fact that the second expedition did locate Aboriginal people lying by their fires on the shores of Botany Bay in the early morning darkness of December 24 – after which they began the return journey to Sydney. But there are no more details on what happened that night.

To return to the key question: was Phillip serious in giving these orders to arrest, shoot and behead warriors? As an eighteenth century naval officer, his actions were not out of character – though grandiose play-acting would have been. Nor did his orders constitute unusual conduct, any more than for succeeding governors, including Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who despatched even larger, and fatal, military reprisal parties against Aboriginal people.[41] Phillip's harsh orders were given to demonstrate his own authority in this precarious colony, to send the unmistakable message to the Eora that 'good', 'friendly' and 'lawful' behaviour would be rewarded with kindness, friendship and indulgence, but violence and killing would result in terror.

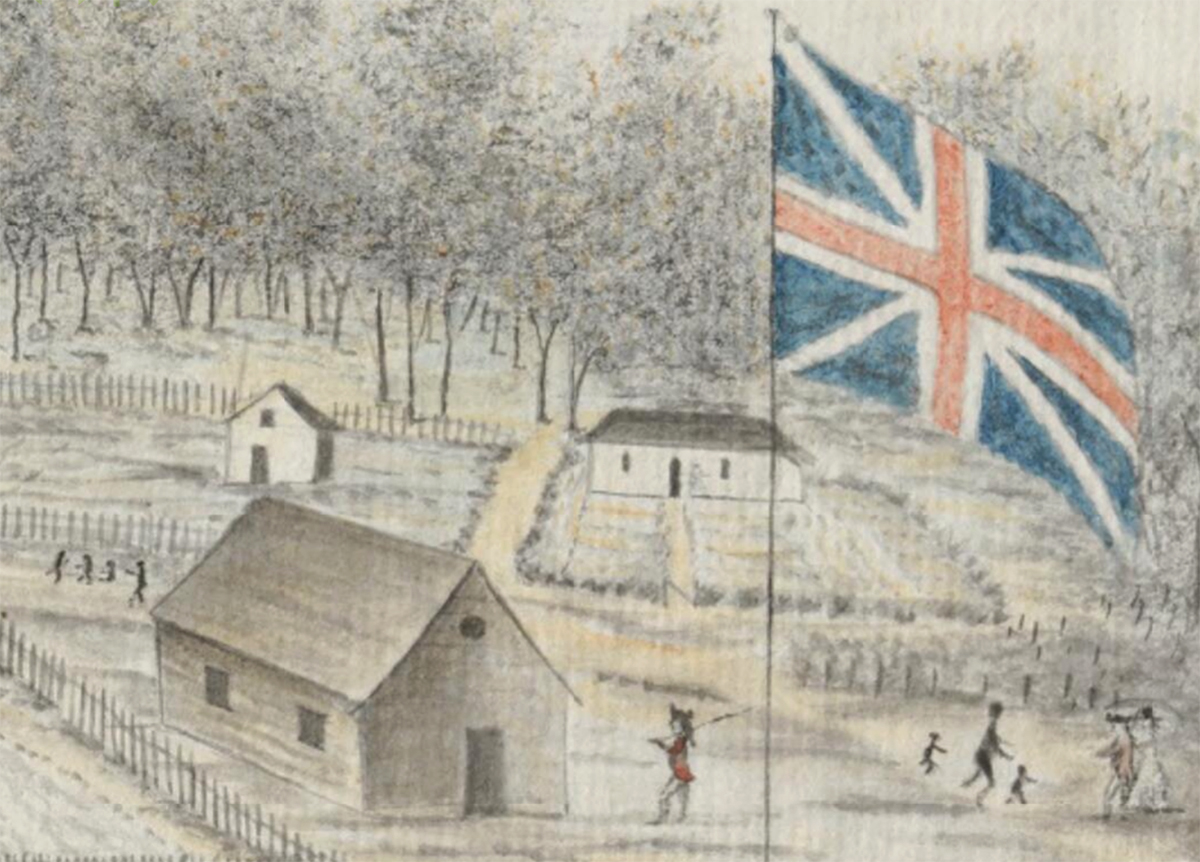

Botany Bay Project

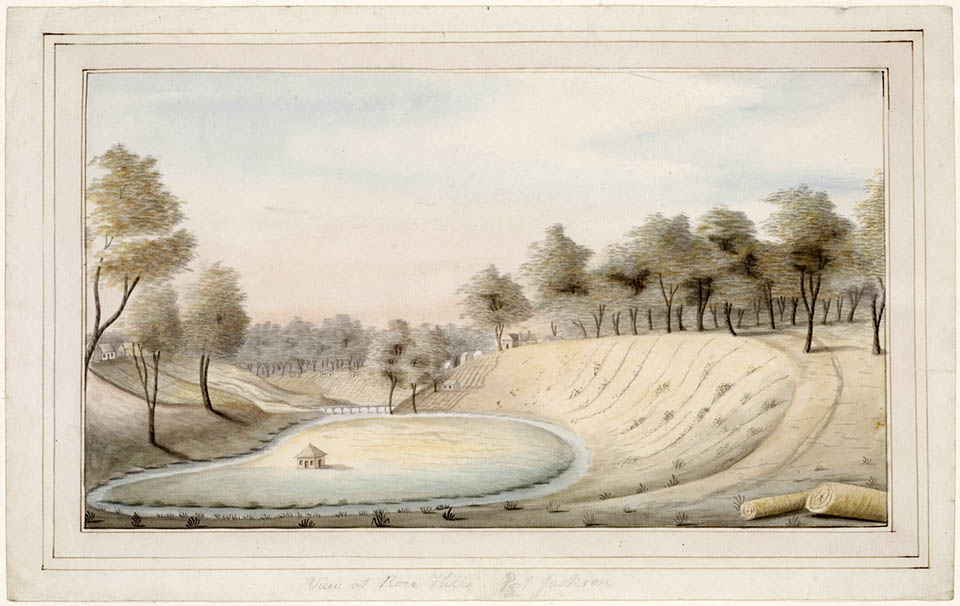

[media]Meanwhile the larger Botany Bay Project was already unfolding up the Parramatta River on the clusters of small, carefully planned farms Phillip had set out there. Here it is important to note that we cannot separate Phillip's relations with Eora and the inland Aboriginal people from his role as the founder of this colony. New South Wales was, after all, never intended as a gaol, or a dumping ground for convicts, but a colony – a rather astonishing penal experiment in making a new society from transported felons. Convicts who were pardoned or had done their time were to be given land and everything they needed to become farmers. They would thus 'cease to be enemies of society… and became proprietors and cultivators of the land'.[42] Phillip himself regarded his most important roles in the founding of this colony as 'serving my country and serving the cause of humanity'.[43] Much of his attention and efforts were devoted to implementing the plan: finding arable soil, experimenting with crops, carving those little farms out of the bush. But the lynchpin of the whole Botany Bay Project, the path to redemption for the convicts, was land, taken from Aboriginal people. And so it was on those early farms that the first signs of frontier conflict broke out in the latter months of 1790.

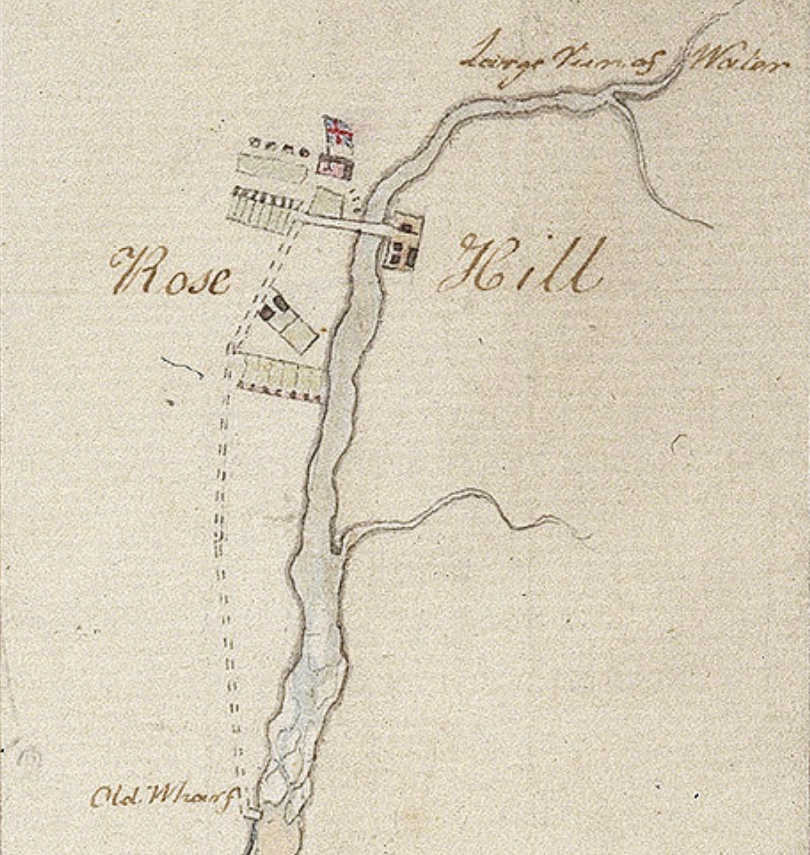

[media]Phillip's first farms were established at and around Parramatta, 23 km west of Sydney. His actions towards the Aboriginal people there were strikingly different to his relations with the Eora on the coast. At Parramatta there were no meetings, no dancing, no gifts or high hopes of 'living in amity'. This is the untold story of Phillip and the Aboriginal people: the settlement of Parramatta was a true invasion, with well-organised military defences. The new public farm there took a large swathe of land right on the river, land the Burramattegal relied upon for food and access to water.[44]

[media]In October 1790, about the same time as Bennelong's triumphant entry into Sydney, one of the Burramattegal elders, Maugoran, came down to protest to Phillip. This was the first recorded formal Aboriginal protest in Australia. Maugoran told Phillip that the people at Parramatta were very angry at the invasion of their country. Phillip noted it all down, but observed bluntly that 'wherever our colonists fix themselves, the natives are obliged to leave that country'. Instead of attempts at compromise or amelioration one might expect from a governor so committed to peaceful relations, Phillip immediately reinforced the detachment at Parramatta with more soldiers.[45]

And when his first ex-convict settlers were placed on the small farms from August 1790 Phillip armed them with muskets. In October a nervy settler at Prospect began indiscriminately shooting into a group of Aboriginal people. They responded by burning down his hut. After that, Phillip posted soldiers on every farm until all the land was clear of trees. Without trees, Aboriginal people would have nowhere to hide.[46]

In subsequent years some Aboriginal people and settlers befriended one another and worked out ways to co-exist. But from the start the Australian frontier was also an edgy place, and guns were the backbone of colonisation. Maize raids, constant attacks on unarmed settlers on the lonely roads, bloody military reprisals, corpses strung up in trees, terrible paybacks on both sides, and massacres were still in the future. But before all that, an ailing Phillip had decided to leave. He never returned.

Phillip’s legacy

How do we interpret Phillip in the light of his actions towards Aboriginal people? Was he a hero or a villain, a good guy or a bad guy? Do we keep him on his pedestal or knock him off? Or, do the twin lenses reveal something else: a pragmatic man in a real and difficult situation? At least two scenarios are possible: one is that Phillip considered the good relations he had established with the Eora of Sydney could and should stand in for his good relations with all Aboriginal people. He had conciliated them, as instructed, and he had done his job.

[media]The second scenario is this: by the time the first farms were being carved out of the bush, Phillip well-knew the fighting power and determination of the Eora warriors, particularly their animosity towards unarmed convicts trespassing in Country. He knew that they were not cowardly, weak people who could simply be moved on, as Cook and Banks had described them. Although plenty of Sydney people now had Eora friends, Phillip's earlier policy of kindness and gifts could not completely stop Eora violence, any more than he could stop settler transgressions. The new farms made the situation still more complex and dangerous. They were spread over a much greater area than the town of Sydney, they were isolated, and they would disrupt many different Aboriginal groups. How would it even be possible to use the policy of patient kindness with all of them?

[media]Phillip knew that farms meant dispossession and dispossession meant violence. But his mission was to found an agricultural colony and he followed his orders to the letter. He armed the convict farmers because he knew that otherwise they probably would not stand a chance out there, either through their own wrongdoing, or because of Aboriginal anger, payback and resistance to the invasion of their lands. Phillip did not want any disasters. The two aspects of Phillip's humane policies we most celebrate contradicted one another: his greatest service to 'the cause of humanity', this extraordinary convict colony, had at its heart not amity, but the inhumanity of dispossession.

[media]But the outcomes of policies and actions can be unexpected. Phillip sailed away in December 1792. One of his legacies was that Sydney was and remained a town of both settlers and Aboriginal people. They shared urban spaces, harbour places, houses, conversations, hunting trips, popular culture. Aboriginal Law continued to be imposed among Aboriginal people in Sydney well in the 1820s and throughout the colony for much longer. The presence of Eora and other Aboriginal people in Sydney town was normal and accepted. This is not a story of instant culture loss and degradation either, for Aboriginal people combined their own dynamic culture with the strands and rhythms of pre-industrial Sydney. Perhaps this explains why Sydney's history of early race relations is so different to Melbourne's, where the local Aboriginal people were evidently subjected to harsh regulation, forced out and banished. Governor Macquarie tried hard to persuade 'the Sydney Tribe' to leave, but they never did. Phillip had invited them in to Sydney, and they were here to stay.[47]

This essay is based on a paper originally presented at The first governor – A bicentenary symposium on Arthur Phillip, held at the Museum of Sydney on the site of first Government House on 5 September 2014 by Sydney Living Museums to commemorate the bicentenary of Arthur Phillip’s death

Notes

[1] This article is based on a paper delivered at 'The First Governor: A symposium in Honour of Arthur Phillip', Museum of Sydney, 5 September 2014.

[2] I use the word 'Eora' in its first recorded sense, meaning 'people', that is, the people of the coastal region around Sydney.

[3] Early accounts about Arthur Phillip and the Aboriginal people include Arthur Wilberforce Jose's 1915 study, in which Phillip was portrayed as kind but embattled, while Aboriginal people were inexplicably savage, just another obstacle in his way (Arthur W. Jose, History of Australasia From the Earliest Times To The Present Day With A Chapter on Australian Literature, Angus and Robertson Ltd, Sydney, 1914, p. 23). Historian Ernest Scott began his 1916 history with the statement: 'This Short History of Australia begins with a blank space on the map and ends with the record of a new name on the map, that of Anzac'. Aboriginal people are not mentioned in his account of the First Fleet’s arrival (Ernest Scott, A Short History of Australia, Humphrey Milford/Oxford University Press, London, 1916, p. v). C.M.H. Clark was acutely conscious of culture clash and the British agenda of dispossession, but his dominant theme was that for Aboriginal people, contact was instant disaster – so the problem was inevitable; there was nothing Phillip could have done about it (C.M.H. Clark, A History of Australia Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Age of Macquarie, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1962, p. 110.). This critical stance swelled in the 1960s and 1970s with the rise of Aboriginal history and the Aboriginal rights movement. The arrival of the First Fleet was now seen as an invasion, not peaceful colonisation, Phillip was no longer kind or wise; and the ‘natives’ were no longer just restless and troublesome – they were resisting the invasion. Anthropologist William Stanner painted Phillip as initially well-meaning but soon disillusioned, but also a fool for failing to recognise Eora protocols (William Stanner, 'The History of Indifference Thus Begins', Aboriginal History, vol. 1, no. 1, 1977, 2-26). A breakthrough in thinking about early race relations in Sydney came via a major archaeological project at the site of Sydney’s First Government House in 1982–83. Archaeologist Isabel McBryde explored the actual relationships between Phillip and the Eora, highlighting the fact that the Eora did not disappear, but were present in early Sydney, inside the yard and walls of the first Government House (Isabel McBryde, Guests of the Governor: Aboriginal Residents of the First Government House, Friends of First Government House Site, Sydney, 1989). Another pioneer of the history of Aboriginal people in Sydney is historian Keith Vincent Smith (Keith Vincent Smith, King Bungaree: A Sydney Aborigine meets the great South Pacific Explorers, 1799-1830, Kangaroo Press, Sydney,1992; Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora Sydney Cove 1788-1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001). Phillip was rehabilitated in Inga Clendinnen’s Dancing with Strangers, which argues that he and the officers were not racist killers but men of the enlightenment who truly saw Aboriginal people as fellow human beings (Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, pp. 5, 286).

[4] See Emma Dortins, 'The many truths of Bennelong's tragedy', Aboriginal History, vol. 33, 2009, pp 53-75. Bennelong has been long depicted as a drunkard who ‘fell between two cultures’ and was rejected by both communities. Yet recent research reveals he married, had at least one son, was a leader among his people and much lamented when he died, see Keith Vincent Smith, Wallumedegal: An Aboriginal History of Ryde, Ryde City Council, Sydney, 2005, pp. 12-13, 25-7; James L. Kohen, The Darug and their Neighbours: the traditional Aboriginal owners of the Sydney region, Darug Link and Blacktown and District Historical Society, Sydney, 1993, p. 55; Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, pp. 422-3.

[5] Greg Dening, Readings/Writings, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1998, pp. 48, 205-18.

[6] Governor Phillip's Instructions,17 April 1787, Historical Records of Australia, series 1, vol. I, pp. 13-14.

[7] Kate Fullagar, 'Bennelong in Britain', Aboriginal History, vol. 33, 2009, p 32.

[8] Arthur Phillip, Memorandum, October 1786, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol. 1, p. 52.

[9] Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003.

[10] See Tiffany Shellam, Shaking Hands on the Fringe: Negotiating the Aboriginal World at King George's Sound, University of Western Australia Press, Crawley, Western Australia, 2009; Stephen J. Kunitz cited in Tom Griffiths, 'Empire and Ecology: Towards an Australian history of the world', in Tom Griffiths and Libby Robin (eds), Empire and Ecology: Environmental History of Settler Societies, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1997, p. 3. Paul Irish's research reveals that Aboriginal people occupied the coastal parts of Sydney continuously throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, see Paul Irish, Hidden in Plain View: The Aboriginal People of Coastal Sydney, NewSouth Books, Sydney, 2017.

[11] Grace Karskens, The Colony, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, p. 48; Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005, pp. 10-15.

[12] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, p. 3; John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, Angus and Robertson, Sydney,1968, (f.p. 1793), pp. 37, 38; George Bouchier Worgan, letter written to his brother Richard Worgan, 12–18 June 1788, includes journal fragment kept by George on a voyage to New South Wales with the First Fleet on board HMS Sirius, 20 January 1788–11, July 1788, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, ML Safe 1/114, p. 10; Pauline Curby, Seven Miles from Sydney: A History of Manly, Headland Press/Manly Council, Manly, 2001, pp 9-10; William Dawes, Vocabulary of the Language of N.S. Wales, in the neighbourhood of Sydney, (Native and English), 1790–9, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Marsden Manuscript Collection, 41645A, 41645b, FM4/343.

[13] Philip Gidley King, Private Journal, vol. 1, 24 October 1786 - 12 January 1789, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW ML Safe 1/16, transcript online at http://image.sl.nsw.gov.au/Ebind/safe1_16/a1296/a1296242.html, entry for 20 January 1788; William Bradley, Journal: A Voyage to New South Wales, December 1786 - May 1792, compiled 1803, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW ML Safe 1/14, p. 60; Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigation the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, pp. 57-60, 29.

[14] Joseph Banks, The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks 1768-1771, 2 volumes, edited by J. C. Beaglehole, Trustees of the Public Library of New South Wales and Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1962, pp. 54-5; Glyndwr Williams, 'Far happier than we Europeans: reactions to the Australian Aborigines on Cook’s voyage', Australian Historical Studies, vol. 19, no 77, 1981, 511; Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005, pp. 11-13.

[15] Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, p. 165.

[16] Grace Karskens, The Colony, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, pp. 55-60.

[17] Grace Karskens, The Colony, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, pp. 49-52; Watkin Tench, A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay, published as Sydney's First Four Years, edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1789), p. 37.

[18] Grace Karskens, The Colony, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, p. 51.

[19] Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora Sydney Cove 1788-1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001, p. 17; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, pp. 15, 17, 45, 81; Watkin Tench, A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay, published as Sydney's First Four Years, edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1789) p. 55; William Bradley, Journal: A Voyage to New South Wales, December 1786 - May 1792, compiled 1803, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW ML Safe 1/14, pp. 85, 119-120, 177.

[20] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, p.16.

[21] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, p16; Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora Sydney Cove 1788-1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001, pp. 23-5.

[22] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, p. 58.

[23] Phillip cited in William Stanner, 'The History of Indifference Thus Begins', Aboriginal History, vol. 1, no. 1, 1977, 3; Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, pp. 29-30, 36.

[24] Their actual legal status remained ambiguous for decades, since they could not give evidence in British courts because they were considered incapable of taking the Christian oath and of understanding the proceedings. See Bruce Kercher, An Unruly Child: A History of Law in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1995, pp. 4-5.

[25] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1793), p. 145; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, pp. 57-8; Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Stranger, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, pp.189, 222.

[26] Grace Karskens, The Colony, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, pp. 371-83; Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003pp. 94-109; Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora Sydney Cove 1788-1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001, pp. 31-7, 39-51.

[27] William Stanner, 'The History of Indifference Thus Begins', Aboriginal History, vol. 1, no. 1, 1977,, 20; Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora Sydney Cove 1788-1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001, pp. 57-9; Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, pp. 110-32; John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, Angus and Robertson, 1968, Sydney, (f.p. 1793), pp. 139, 141; Arthur Phillip, Journal (in John Hunter, Historical Journal), pp. 305-8; Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1793), pp. 176-80; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, pp. 132-4; William Bradley, Journal: A Voyage to New South Wales, December 1786 - May 1792, compiled 1803, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, ML Safe 1/14, p. 229.

[28] Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, pp. 133-9; Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora Sydney Cove 1788-1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001, chapter 9; Grace Karskens, The Colony, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, pp. 386-9; re Bennelong's gunya see Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1793), p. 200; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, p.137.

[29] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1793), pp.183, 200; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, pp. 133, 135.

[30] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, pp. 329, 587; Karskens, The Colony, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2010, p. 358. See also Lisa Ford, Settler Sovereignty: Jurisdiction and Indigenous people in America and Australia 1788-1836, Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass., 2010, pp. 43-4.

[31] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1793), pp. 205-6;

[32] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1793), p. 207-8

[33] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1793), p. 209. As Keith Vincent Smith points out, Phillip also appears to have been under pressure to provide Aboriginal skulls for Sir Joseph Banks, who had promised them to medical professor Johann Fredrich Blumenbach at the University of Göttingen. This may explain the 'headhunt'. Blumenbach did in fact acquire two skulls of initiated men from the Sydney region in the 1790s, but their identities are unknown. Certainly later outlawed warriors were beheaded, including Pemulwuy himself in 1802 and two warriors and a woman killed during the Appin massacre of 1816. See Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora Sydney Cove 1788-1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001, pp. 156-7; Grace Karskens, The Colony, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, pp. 474, 513-14.

[34] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1793), pp. 209-11.

[35] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979 (f.p. 1793), pp. 212-15.

[36] Private John Easty, Book. A Memarandom of the Transa…of a Voiage from England to Botany Bay in the Scarborough Transport Gaptn Marshall Commander kept by me your humble Servan, Nov 1786-May1793, Dixson Library, State Library of NSW Safe/DLSpencer 374, transcript online at http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/_transcript/2014/D31314/a1145.html , p. 122; compare with Phillip, 'they did not see a single inhabitant during the two days which they remained out', Journal, in John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, Angus and Robertson, Sydney,1968 (f.p. 1793),), p. 329.

[37] Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora Sydney Cove 1788-1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001, p. 90.

[38] Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, pp.172-81.

[39] Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora Sydney Cove 1788-1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001pp. 86-7; Phyllis Mander-Jones, 'Dawes, William (1762-1836)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol.1, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne,1966, pp. 297-8.

[40] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, 144; Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora Sydney Cove 1788-1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001, p. 89.

[41] Grace Karskens, The Colony, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, pp. 466, 507-14; John Connor, The Australian Frontier Wars 1788-1838, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2000, p. 38ff.

[42] Alan Atkinson, The Europeans in Australia: A History Volume One The Beginning, Oxford University Press, 1997, Melbourne, pp. 64-72; quote Johan Reinhold Forster p. 68

[43] Arthur Phillip to Lord Sydney, 10 July 1788, cited in Michael Pembroke, Arthur Phillip: Sailor, Mercenary, Governor, Spy, Hardie Grant Books, Melbourne, 2013, p. 156.

[44] John Connor, The Australian Frontier Wars 1788-1838, UNSW Press, Sydney, p. 26; compare with Arthur Phillip, Journal, (in John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1968 (f.p. 1793), p. 299; James L. Kohen, A. Knight and Keith Vincent Smith, 'Uninvited Guests: An Aboriginal Perspective on Government House and Parramatta Park', report prepared for the National Trust of Australia (NSW), August 1999, p. 16.

[45] Arthur Phillip, Journal (in John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1968 (f.p. 1793), p. 312; Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years edited by L. F. Fitzhardinge, Library of Australian History, 1979, Sydney (f.p. 1793), p.181.

[46] Arthur Phillip, Journal (in John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1968 (f.p. 1793), pp. 299, 355-6; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, facs. ed. Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971 (f.p. T. Cadell and W Davies, London, 1798), vol. 1, p. 450; Governor John Hunter to Portland, 3 Mar 1796, Historical Records of Australia vol. 1, p. 55.

[47] See Penelope Edmonds, Urbanizing Frontiers: Indigenous Peoples and Settlers in 19th Century Pacific Rim Cities, University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, 2010; Grace Karskens, The Colony, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, Chapters 12, 14; Paul Irish, Hidden in Plain View, NewSouth Books, Sydney, 2017.