The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Boatswain Maroot

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Boatswain Maroot

[media]Boatswain Maroot, who said he was born about 1793 at the Cooks River (Gumannan) near Botany, was the son of Maroot, an elder (c1773-1817) of the Kameygal (or Gameygal) people that occupied the north shore of Kamay (Botany Bay), and Grang Grang.[1]

The son would lead a very different life to that of his father. He gained the nickname 'Boatswain' or 'Bosun' as a young man, sailing on English ships in sealing and whaling voyages to Macquarie Island in the sub-Antarctic and the New Zealand 'whale fisheries'. His name was also interpreted variously as Merute, Mahroot, Maoroo, Mirout, Young Mirouth and Meroot. In 1820 the Russian artist Pavel Mikhailov sketched a portrait of 'Movat' (In Russian 'Mowat', or Maroot) with Salamander on the north shore at Kirribilli while two ships of the polar expedition commanded by Captain Fabian von Bellingshausen were in Sydney.[2]

On 8 September 1845, when he said he was about 49 years of age, Boatswain Maroot gave evidence to the NSW Legislative Council's Select Committee on the Condition of Aborigines. In the answers he gave to questions from Dr John Dunmore Lang and others, he spoke frankly about his life, his family, his Gameygal country and the impact on Indigenous people since the coming of the British.[3]

Street fights

Boatswain Maroot was twice wounded as a young man in ritual battles in the streets of Sydney, but admitted in later life that he had little knowledge of Aboriginal spirituality and had not lost a tooth, in other words, he was never initiated.[4]

In January 1805, the Sydney Gazette reported a fight over a woman in which 'young Mirouth' received a 'knock down blow from Bidgywidgy', or Bidgee Bidgee, from the Burramattagal or Parramatta people.[5] If his date of birth is correct, he would have been about 13 years old at this time.

A year later 'Young Mirout' met Musquito, another Gameygal youth[6], in battle outside the military barracks after Musquito had severely wounded young Pigeon, a boy from the Shoalhaven, with a tomahawk.

They came repeatedly to close quarters with the waddy and never separated without inflicting severe wounds on each other. The contrast that was presented in the conduct of the competitors interested the spectators in behalf of Mirout, whose cool and determined intrepidity, in exposing himself to assault, added to his generosity in declining ever species of advantage that might have been embraced to the certain overthrow of his opponent lay claim to admiration, and was followed by regret, when, from an unexpected stroke he [Boatswain] fell, and receiving another on the ground his head was laid completely open.

Maroot recovered, but that night another young Aboriginal man named Blewit from Botany Bay, speared Musquito under the heart in front of the General Hospital at The Rocks, where he died.[7]

Maroot's petition

Boatswain Maroot was one of the first Indigenous men from the Sydney area to work on the colonial sealing and whaling ships that sailed down the coast to Van Dieman's Land and Macquarie Island. In his evidence to the Select Committee in 1845, he said he 'went out whaling five or six' times, and that it was 'dirty work, and hard'.[8]

His first documented voyage began in July 1809 when Maroot left Port Jackson on the Sydney Cove, a sealing and whaling ship managed by Kable & Underwood that was setting forth for the fisheries to the south.

There he and other crew were left on Macquarie Island in the sub-Antarctic without sufficient supplies. There were no land-dwelling animals to hunt on Macquarie Island and the high cliffs made fishing difficult and the men were forced to live on a diet of seals, salty penguins and mutton birds. Even in summer the island was swept by icy winds and had a mean temperature of 4 degrees Centigrade, a cruel climate for an Aboriginal man from Botany Bay. Months after their food rations ran out, Maroot and two European sealers stowed away on the 150-ton brig Concord which had been sent to the island to re-supply work gangs stationed there, and returned to Sydney on Friday 4 October 1811.[9]

Eight days after his return 'Merute' addressed his petition to Governor Macquarie, claiming a breach of verbal contract, the first known civil case made by an Aboriginal person. In it he claimed that he had entered into a verbal agreement with James Underwood, and 'did double duty to a white man' but had not been paid anything.[10]

Underwood eventually consented to give Maroot ten pounds owed to him in wages, half to be paid in money and half in goods, on condition that he discharged his claims upon the ship.

Other voyages

On 8 February 1822, a 'Claims and Demands' notice appeared in the Sydney Gazette:

BOATSWAIN, a black native, of the Brig Mercury, leaving the Colony in the said Vessel requests Claims to be presented.[11]

Included with Boatswain in the 156-ton whaling ship's muster were Bulkabra (Bolgobrough), Jem and Tommy, described as 'Black Natives inserted in Ship at an 1/160th share'.[12] The Mercury 'sailed for the sperm whale fishery' on 1 March 1822.[13]

The Mercury again left Sydney for the whale fisheries on 22 October 1822. The ship's muster of 'Black Natives — Shipped this Voyage' listed three other Aboriginal men as well as Boatswain Maroot - Bulkabra, Tommy and William (Willamannan or William Menan, Bulkabra's brother).[14]

Bulkabra and Boatswain again served on the Mercury, which sailed for Van Diemens Land and Macquarie Island in May 1823. A note in the muster under Boatswain's name reads 'Discharged ex Midas Dec 1822. Saw discharge.'[15]

In 1845, Maroot said he had earned about twenty or thirty pounds a voyage when he went whaling, and when asked by Dr Lang what he'd done with it said, he'd gone out drinking with the other sailors:

Maroot: I went along with the sailors and we threw it away all together.

Dr Lang: In the Public Houses?

Maroot: Yes, and then go for more again as soon as ever that was all out.

In a letter written in the 1850s, John Perrell Wilkie said Boatswain and another Aboriginal man named Dick had worked for him at Otago, New Zealand and had both been promoted to the position of Boatsteerer and paid 'the same as white men'.[16] Boatsteerers were trusted and skilled seamen who took up the position of harpooner when a whale was sighted.

'all this my country! pretty place Botany!'

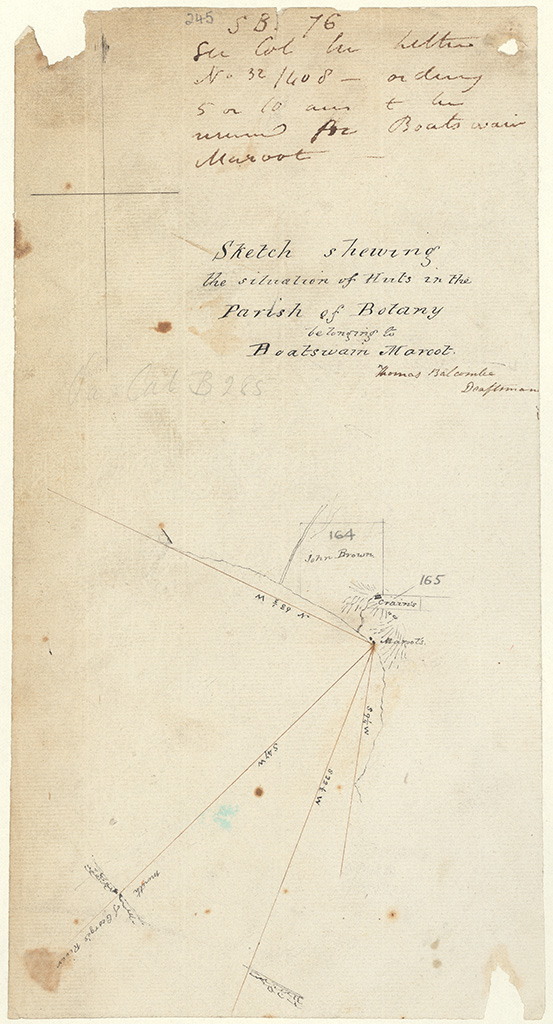

[media]Home from the sea, the enterprising Boatswain settled down once more in Gameygal country, of which he was reported to say 'all this my country! pretty place Botany'.[17]

From the success of his petition for compensation in 1811, Maroot had learned to negotiate with the English authorities who had appropriated his country. In 1832, by sheer persistence and frequent visits to the office of Governor Sir Richard Bourke, Boatswain was given a 10-acre (4.05 hectares) lease on the north shore of Kamay (Botany Bay).

In a Minute to the Colonial Secretary on 17 April 1832, Bourke noted that 'Boatswain Mahroot, an aboriginal Native has called at the office repeatedly respecting some Land at Botany, promised to him, as he says, by the Governor, and on which he has two Huts.' Bourke added: 'Let him … be informed that he may take possession, but it will not be necessary to give him a written document as care will be taken that he is not disturbed, and he would probably lose the document.'[18]

Thomas Balcombe's survey map shows Boatswain Maroot's lease, situated on the swampy Botany Bay shoreline close to Bumborah Point, just below 'Bunnerong', a parcel of land belonging to John Brown and another marked 'Crain's' [John Crane], close to a creek running into the bay.[19]

There he built slab timber huts, renting some out to tenants[20], and used his own boat to make a living through fishing and taking Europeans on fishing excursions.[21]

In 1845, Boatswain said he obtained a living from the 'white fellows' by working with his wife catching fish, which another Aboriginal man then took to Sydney by cart. At one time 'a good while ago', he made £4 to £6 per week by fishing, which he spent on clothing, meat, flour and sugar. He grew cabbages and pumpkins until cows knocked down the garden fence. He built more huts on his land but now 'hardly got four shillings a week, from rentals'.[22]

His tenants, at various times, attempted to have him evicted from his lease but were unsuccessful due to his support from the Governor.[23] Boatswain's attempts to buy the land outright however came to nothing.

Guest of honour

On Christmas Day in 1844, Charles Smith, a successful butcher and popular philanthropist in the city, held a Christmas Day feast for abour forty people of the 'Aboriginal tribes of Woolloomooloo and Shoalhaven', at his home on the corner of Market and George Streets. Boatswain, along with Tarban and a woman identified only as 'a Queen of the Tribe' were the guests of honour. Smith and his domestic staff waited on the guests, offering them traditional English Christmas fare of roast beef, mutton and plum pudding. The guests drank Smith's health in ale, porter and wine, and each man received a new shirt as a present.[24]

Language

Boatswain Maroot was a proficient English speaker when he made his petition in 1811, but he said in 1845 that he had learned English while living with Deputy Commissary General David Allan, who had been living in Sydney from 1813 to 1819.

In April 1832 Maroot told the German missionary Reverend Johann Handt that there were only four of the 'Botany Bay Tribe left. Handt wrote: 'He is now a civilized man, and by profession a Sailor … I saw him only once, and then asked him about the language of his own Tribe, but it appeared that he had forgotten much of it … I did not see him since that time, and suppose therefore that he has gone to sea again.'[25]

Maroot may have been prevaricating about his knowledge of his language as, in 1849, when blankets, bread and beef were distributed to the 'remnant of the Sydney Aborigines' on the Queen's Birthday, 24 May 1849, Boatswain gave a speech 'at some length; in his native language' and proposed a toast in bull (watered-down rum) to Queen Victoria and the Governor.[26]

Maroot told the Select Committee that the territory of the Liverpool Aborigines (Cabrogal), with whom his people had often fought, met Gameygal country at the Cooks River, and that while they spoke a different language, as did the Five Islands (Illawarra) people to the south, there were enough similarities between the languages to make themselves understood.[27]

Often reported as saying he was the only one left of his people, when asked how many people still spoke his language rather than the Liverpool language, he replied 'Only four, three women and I am the only man.'[28]

Family

Boatswain said in 1845 that he had a wife who he lived and worked with at Botany, but had never had any children. Unfortunately his wife is not named. He had no brothers, but 'three sisters by another father and the same mother'. One of his sisters, Maria, also lived at Botany.[29]

He recalled a 'tribe' that numbered about 400 people at Botany Bay when he was a child, but was recorded at various times as saying they were all gone 'All gone! only me left to walk about'[30] and was the last of his people. The other three women who spoke his language don't seem to have been included in this tally however.

Later in the 1840s he spoke of his sorrow at the death of his wife:

Poor gin mine tumble down, [die]. All gone! Bury her like a lady, Mitter—; all put in coffin, English fashion. I feel lump in throat when I talk about her; but,—I buried her all very genteel.[31]

Last days

According to the one author, 'old 'Boatswain'' spent the last years of his life in a 'guneah' (gunyah or gonye) bark shelter in the grounds of the Sir Joseph Banks Hotel at Banksmeadow.[32]. In October 1849 some sporting gentlemen accused Boatswain of 'walking off with our marine' (stealing their boat), while they were 'taking a view of the [hotel's] zoological collection'.[33]

Boatswain Maroot died at Botany on 31 January 1850. The Sydney Morning Herald reported:

At Botany on the 31st Jan, the well-known aboriginal “Boatswain,” whose intelligence and superior manners, coupled with the fact of his being the last of the Botany Bay tribe, rendered him a favourite with all who knew him, and especially with his white countrymen.[34]

Boatswain was buried in the garden at Botany near the beach, a long-established Aboriginal burying ground.[35]

References

Keith Vincent Smith, 'Boatswain Maroot in the sub-Antarctic', Chapter 14 in MARI NAWI: Aboriginal Odysseys, Rosenberg, Dural, 2010,146-156.

Notes:

[1] ''Meroot' was the Father and 'Grang Grang' the Mother of old 'Boson'[Boatswain Maroot] of Botany', George Thornton Papers, 'NSW Aboriginal', MS 3270, National Library of Australia, Canberra; W. Augustus Miles JP, 'How did the natives become acquainted with demigods and daemonia …?', Journal of Ethnological Society of London, Vol III, London 1854, 4-50. We can't know if this Grang Grang is Bennelong's sister Carangarang or another woman with a similar name Carangarang as there is no evidence.

[2] 'Movat 1820' [Mowat, i.e. Boatswain Maroot], Pavel Mikhailov (1786-1840), pencil and sanguine on brown paper, R29209/207, Russian State Museum, St Petersburg

[3] Mahroot, alias the Boatswain, 'Report from the Select Committee of the Condition of the Aborigines', Votes and Proceedings, New South Wales Legislative Council, Government Printer, Sydney, 1845

[4] Mahroot, alias the Boatswain, 'Report from the Select Committee of the Condition of the Aborigines', Votes and Proceedings, New South Wales Legislative Council, Government Printer, Sydney, 1845

[5] Sydney Gazette, 13 January 1805, 3a

[6] This Gameygal Musquito was not the notorious Mosquito or 'Bush Muschetta' from Broken Bay, who was sent to Norfolk Island by Governor Philip Gidley King in 1805 and in 1813 to Van Diemens Land (Tasmania) and hanged for an alleged murder in Hobart Town in 1825. See Naomi Parry, 'Musquito (1780-1825)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2005; Hobart Town Gazette, 29 October 1824

[7] Sydney Gazette,12 January 1806, 1c

[8] Mahroot, alias the Boatswain, 'Report from the Select Committee of the Condition of the Aborigines', Votes and Proceedings, New South Wales Legislative Council, Government Printer, Sydney, 1845

[9] Sydney Gazette, 3 October 1811, 2c

[10] Merute's petition, 9 October 1811, Colonial Secretary Papers Minutes and Proceedings, Bench of Magistrates, County of Cumberland, Sydney District, Reel 658; SZ773 - unpaginated, State Archives & Records NSW

[11] Sydney Gazette, 8 February 1822, 4b

[12] Colonial Secretary, Ships Musters, 4/4773, COD/419 No. 13, State Archives & Records NSW

[13] Ship News, Sydney Gazette, 1 November 1822, 3

[14] Colonial Secretary, Ships Musters, 4471, No 688, Brig Mercury, 22 October 1822, Reel 561:456, State Archives & Records NSW

[15] Colonial Secretary, Ships Musters, 4/4773, COD/419, State Archives & Records NSW

[16] John Perrell Wilkie, ALS to Henry Hughes, 25 October 1852, DL DOC 14, Dixson Library, State Library of NSW

[17] Joseph Phipps Townsend, Rambles and Observations in New South Wales, London, 1849, 120

[18] Governor's Minutes, Minute No. 1836, 17 April 1832, Col. Sec. Archives, Governor's Minutes 1832, 4/996, State Archives & Records NSW

[19] Cumberland County Botany – Sketch showing the situation of Huts in the Parish of Botany belonging to Boatswain Maroot 1830, draftsman Thomas Balcombe [Sketch book 1, folio 76], NRS13886 [X751]_a110_000245, State Archives & Records NSW; John Crane, who owned 10 acres adjoining Boatswain Maroot, was an ex-convict, pardoned in 1826, who became a shoemaker and leather seller in Prince Street, Sydney. John Neathway Brown, an army veteran, was granted 100 acres with a northern boundary bordered by the Cooks River and Sheas Creek. The New South Wales Calendar and General Post Office Directory in 1832 said the Sydney to Botany Road (a former Aboriginal muru or pathway) crossed 'at about six miles [from Sydney], a fine running brook of water, near MR. BROWN'S farm'. This was later named Bunnerong Road and the 'brook' Bunnerong Creek. Samuel Bennett, The History of Australian Discovery and Colonisation, Sydney 1865, 84

[20] Mahroot, alias the Boatswain, 'Report from the Select Committee of the Condition of the Aborigines', Votes and Proceedings, New South Wales Legislative Council, Government Printer, Sydney, 1845; Joseph Phipps Townsend, Rambles and Observations in New South Wales, London, 1849, 120

[21] Botany Bay, Sydney Morning Herald, 28 January 1861, 5

[22] Mahroot, alias the Boatswain, 'Report from the Select Committee of the Condition of the Aborigines', Votes and Proceedings, New South Wales Legislative Council, Government Printer, Sydney, 1845

[23] Paul Irish, Hidden in Plain View: The Aboriginal People of Coastal Sydney, New South Books, Sydney, 2018, 46-47

[24] Aboriginal Christmas festivities, The Australian, Sydney, 27 December 1844, 3; THE LATE MR. CHARLES SMITH, Bell's Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 20 December 1845, 2

[25] Reverend J. S. Handt, Bonwick Transcripts, BT Box 54, p. 1855, Mitchell Library, Sydney

[26] Sydney Morning Herald, 26 May 1849, 2

[27] Mahroot, alias the Boatswain, 'Report from the Select Committee of the Condition of the Aborigines', Votes and Proceedings, New South Wales Legislative Council, Government Printer, Sydney, 1845

[28] Mahroot, alias the Boatswain, 'Report from the Select Committee of the Condition of the Aborigines', Votes and Proceedings, New South Wales Legislative Council, Government Printer, Sydney, 1845

[29] Maria Maroot in Paul Irish, Hidden in Plain View: The Aboriginal People of Coastal Sydney, New South Books, 2018, 46

[30] Journal of the Ethnological Society, London, 1854, vol. 111, 1-50

[31] Joseph Phipps Townsend, Rambles and Observations in New South Wales, London, 1849, 120

[32] GC Mundy, Our Antipodes, London, 1855, 31

[33] Bell's Life in Sydney, 13 October 1849, 2

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday, 2 February 1850, 5

[35] Evening News, Sydney, 12 June 1913, 7; The Sun, Sydney, 27 November 1913, 7