The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Darwin's Walk, Wentworth Falls

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Darwin’s Walk, Wentworth Falls

'Walk it and you are part of it …', Iain Sinclair

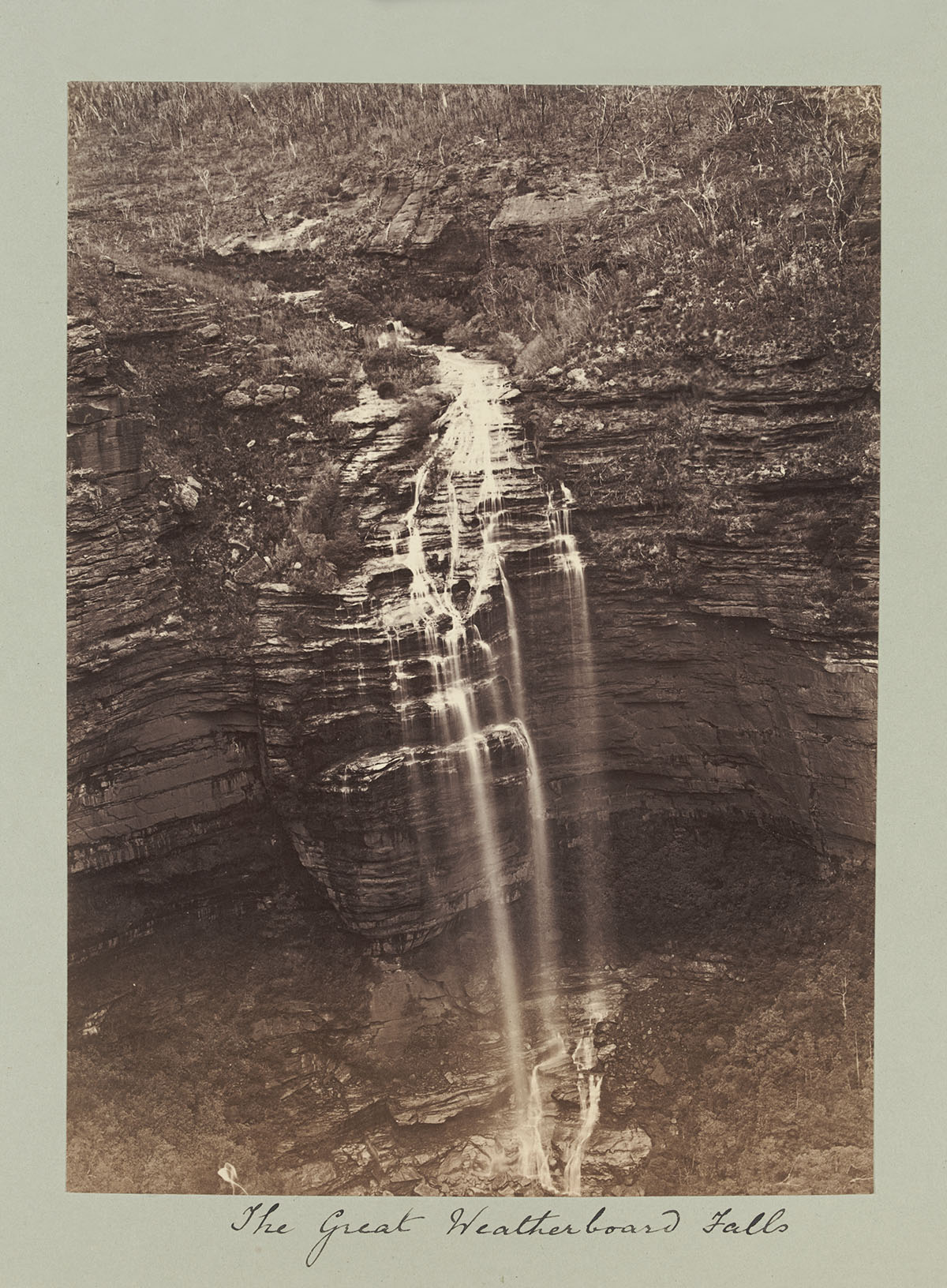

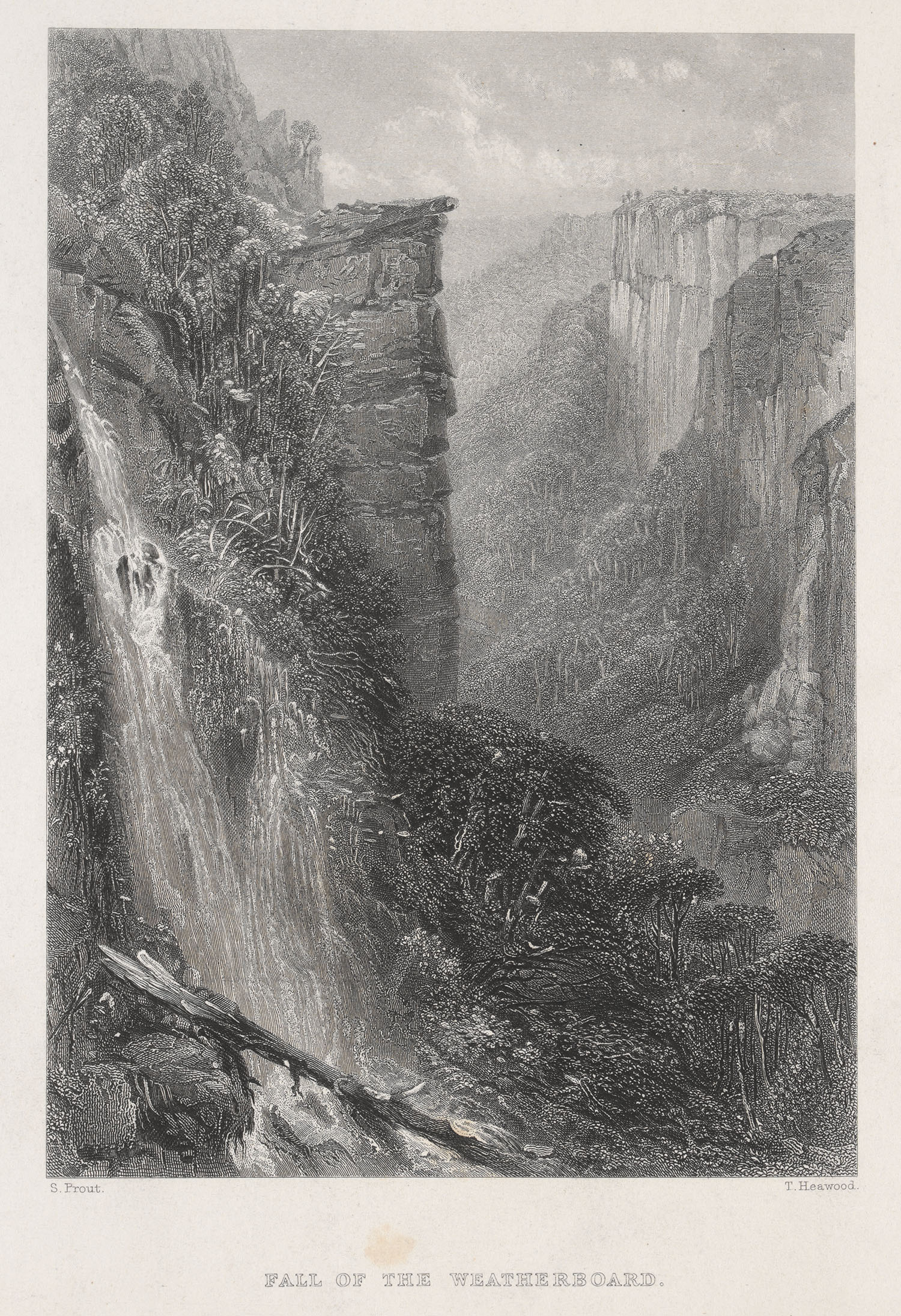

[media]In the winter of 1815, Lt William Lawson of the Royal NSW Veteran Company drove a hundred head of cattle across the Blue Mountains to Bathurst. It was cold and unusually wet and his passage along the newly opened road was hampered as much by weather as by the landscape itself. On his return, seeking shelter 'in the dead of night' in the hut at Jamison Creek (now Wentworth Falls), he burst in upon another group of sleeping travelers. Framed in the doorway, the storm howling at his back, 'with his meager face, being wet, cold and starved with a blanket over his shoulders,' he appeared to the startled Rowland Hassall, recently appointed Superintendent of Government Stock, as a ghostly apparition conjured as if from the land itself. [1]

[media]The old weatherboard store hut, erected by William Cox a year earlier during the construction of the road, had become a refuge for travelers like Lawson and Hassall. The only substantial shelter for miles, it faced the road with an area of open ground at its back, the course grass there valuable as animal fodder and with 'a rivulet of fine spring water running through it'. [2] Two years earlier Lawson had camped there with his companions and their horses and even when later damaged by fire, the 'burnt weatherboard hut' continued to provide refuge until eventually supplanted, in the late 1820s, by a proper inn on higher ground on the other side of the creek. A pointless attempt to name the new hostelry the 'Bathurst Traveler' failed in the parliament of popular usage. It became and remained the 'Weatherboard Inn'.

Following the sound of the water

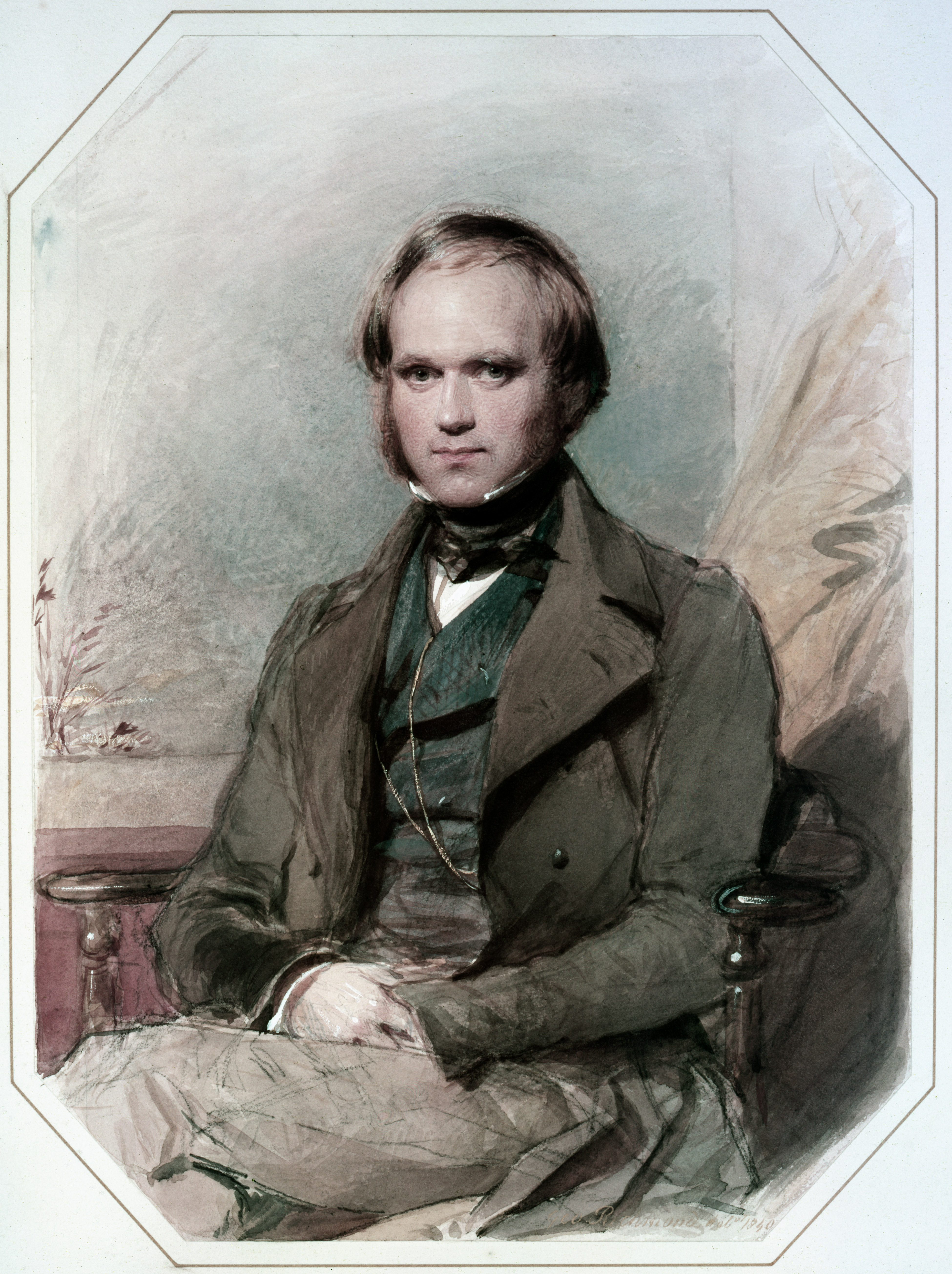

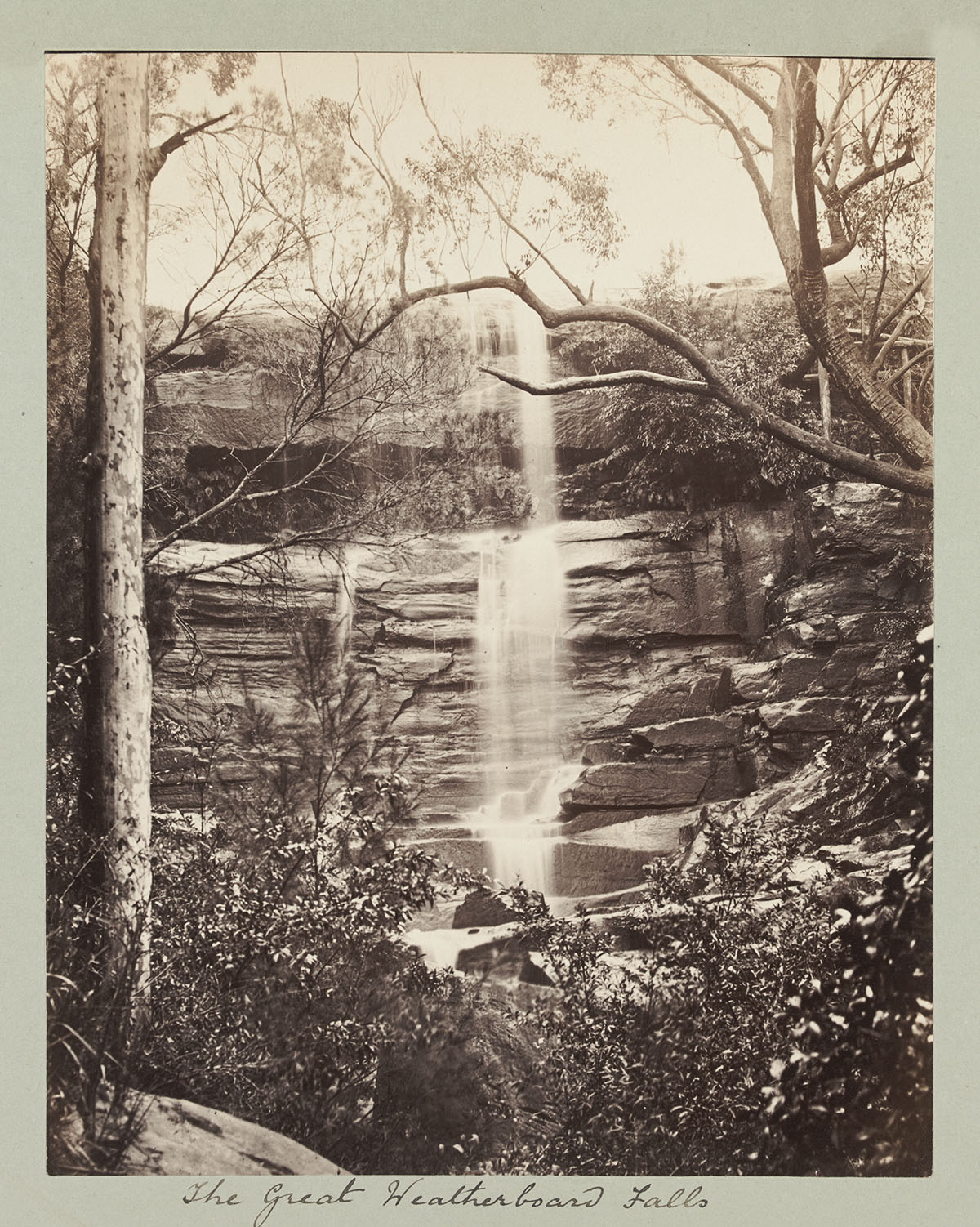

[media]As the European presence reworked the landscape, the one constant remained the sound of Jamison Creek tracing a course down the small hanging valley to its ultimate leap into space; the spot where everything else – rock, plant, flesh and mind – teeters on the edge of the great stone bowl of the Jamison Valley and time shifts into geological scale. It was here, having followed down the 'tiny rill of water', that Charles Darwin stood on a hot January day in 1836, struggling for words to describe the 'quite novel' scene before him, the 'immense gulf' and the 'absolutely vertical' sandstone cliffs where 'a person standing on the edge and throwing down a stone, can see it strike the trees in the abyss below'. [3] A fascination with 'awful heights and dreadful depths connected by falling water' [4] offered travelers another reason to break their journey at 'The Weatherboard'.

[media]Untouched, to my knowledge, by archaeology, evidence from similar environments suggests that human feet have been treading a path along Jamison Creek since the end of the last Ice Age, when a warming climate began to turn such small watered valleys into oases in an increasingly arid landscape. [5] In more recent times, perhaps a convict or soldier stationed at Cox's depot, curious enough to steal some time to explore his surroundings, became the first European to follow the creek. The naming of the small valley and its creek after his friend Sir John Jamison and the great waterfall at the valley's extremity for his secretary John Campbell, suggests that Governor Macquarie too might have followed the sound of the water during his grand tour in 1815.

The Weatherboard Inn

[media]It was, however, primarily after the opening of the inn that word-of-mouth and the active encouragement of the early innkeepers turned the track into what local naturalist, historian and walker Jim Smith claims as the earliest 'tourist' walking track in the Blue Mountains. [6] An antipodean 'old way' infused through the years with memory and story, it is now 'Darwin's Walk' in recognition of the visitor whose 'story', more than any other, changed the way we think about the world. [media]But in January 1836 the young naturalist from the Beagle was unknown. His ideas were still forming and almost five years into a voyage that was meant to last only three, he was feeling the effects of recurrent illness (probably a hereditary mitochondrial disorder [7]) and anxious to get home. Weariness, nevertheless, did not dampen his curiosity or capacity for physical exertion for, four days after disembarking into the heat of an Australian summer, on 16 January Darwin 'hired a man and two horses to take me to Bathurst, a village about one hundred and twenty miles in the interior'. Pausing at Emu Ferry (now Penrith), he crossed the Nepean River the following morning and 'in the middle of the day…baited our horses at a little inn, called the Weatherboard'. Before riding on he visited the falls and then, six days later, returning from Bathurst, 'slept at the Weatherboard, and before dark took another walk to the amphitheatre'. [8]

Today the site of the inn, a disturbed piece of ground beside a sports oval, is only a short walk up the hill from the Wentworth Falls railway station. It is marked by an Evergreen English Oak planted in January 1936 by the President of the Field Naturalists' Club of NSW during a ceremony to mark the centenary of Darwin's visit. Local council bulldozers accidentally uncovered some foundations in the 1980s and a hasty archaeological excavation unearthed the usual flotsam of brick, pottery, clay pipes, nails etc before it was all covered up again. [9] There was talk of creating a historical precinct and some years ago a protective fence was thrown around it, with an interpretive historical marker positioned to inform the curious.

Darwin's walk

[media]I have walked in Darwin's steps on numerous occasions and in all weather, in the heat of summer and on days of cold, drizzling rain. While the 'modern' walk begins through a grand entrance in Wilson Park, on the southern side of the Great Western Highway, I always start where Darwin himself did, at the site of the Weatherboard Inn. On a warm day, even with the fence, the spreading branches of the Darwin's tree create a pool of shade, a good place to reflect for a moment and adjust the mind to nature and past times. Walking as an act of sorcery, an occult summoning of spirits!

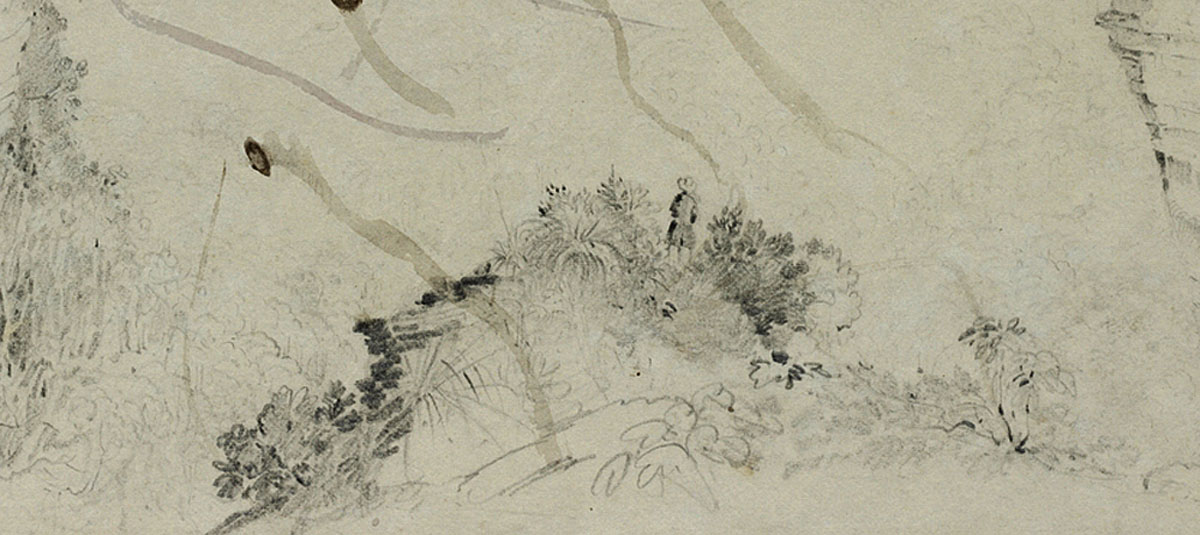

[media]Ironically, Darwin recorded little of the minutiae of his walk; it was the geology of the great 'gulf' (decoding the rocks was all the rage at home) that occupied his attention. Fortunately, this was not the case with two other contemporary naturalists, one who preceded him by two years and one who followed three years later. In June 1834 the haughtily self-reliant Austrian aristocrat and botanist, Baron Charles von Hugel, hired a gig and drove alone over the Blue Mountains to Bathurst, sleeping at the Weatherboard Inn and describing it as 'a wretched place, despite its pretensions'. It was very cold when he woke the next morning but he rose early, assembled his botany bag and seed-papers and, with one of the inn's stable-hands as a guide, set off for the falls before breakfast. He found the track neglected and the going difficult:

'Just two men', he remarked in his journal, 'could make an excellent track to the waterfall in a single day but, as things are, you can hardly get through. Only by taking considerable leaps across the stream, which has cut a deep bed in some places with over-hanging banks, is it possible to reach the falls with half-dry feet.' He noted the presence of interesting plants and concluded that it was, despite the difficulties, 'worth getting wet feet to see these falls'. [10]

[media]Artist and naturalist, Louisa Meredith, returning from Bathurst in the hot November of 1839, also walked to the falls and 'wet her feet in the creek', though she did so 'with no very great objection to a splash if one's foot slipped'. Following 'the borders of a bright brook that…gurgled and glittered over its rock bed', she joyfully embraced the experience, finding among the reeds of the creek 'the great green frogs and bright dragon-flies', discovering a delicately beautiful 'fringed violet…growing alone on a thin transparent stem' and coming upon 'a group of eight or ten splendid waratahs, straight as arrows' that she felt would have been 'sacrilege' to pick. After the heat and dust of the Western Road, she reveled in the 'moist greenness' of it all, reviving her flagging spirits through these small encounters. [11]

With the coming of the railway in the late 1860s and the construction of a carriage road to the falls to accommodate the visit in 1868 of Queen Victoria's son, Prince Alfred, the creek-side track entered a long period of neglect. Despite some interest in the 1920s that flagged in the face of private property rights, it took another half century and the approach of the 150th anniversary of Darwin's visit to rouse enough community concern to initiate a successful project to re-establish the track as an accessible public walk. [12]

In mid-January 1986, I was one of a large crowd who, accepting an invitation from the local artist Renis Zusters and his friend Dr Peter Stanbury of the Macleay Museum, set out to retrace the naturalist's steps in a colourful little drama of remembrance. At one of the many turns in the track, Darwin himself, in the guise of actor Tim Elliot, was suddenly among us and remained our companion for the rest of the walk, humbly assisting in the unveiling of a commemorative plaque attached above the path just before the 'immense gulf unexpectedly opens through the trees'. The aging plaque, now easily missed, is still there and reads: 'Charles Darwin passed this way in 1836, remembered by his friends in 1986.' [13]

The 'new' Darwin's Walk opened at the end of the 1980s and when the 170th anniversary arrived in January 2006 my young daughter and I walked a much improved path. Steps, sections of raised boardwalks, bridges and hopping-stone creek crossings had all enhanced the rough track of earlier years. Though Louisa might have been disappointed, the Baron's feet would now have remained dry!

Memory-mapping

Much has changed since Darwin's time with exotic weed invasion and encroachment of residential properties but the creek still wanders through a rich variety of vegetation and plant communities, from the immediate riparian environment to hanging swamps and areas of open forest, all of which we human drifters share with a host of non-human creatures. The Giant Dragonfly and the Blue Mountains Water Skink, both endangered, find refuge here. Honeyeaters are drawn to the nectar-rich banksias found along the track, the thin rasp of Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoos haunt the high tops and perhaps, during the breeding season, a male Satin Bowerbird will arrange love tokens in a secluded bower. They 'think about blue like words' [14] wrote the poet David Campbell. So many worlds that are not ours, but somehow made familiar by walking!

[media]There are pools and shadowed retreats along the creek and in several places the water tumbles over small waterfalls and cascades that become more pronounced the closer one gets to the falls. For many people certain of these spots have taken on special meaning, their memory remaining with them and even shared with others. At one time, Weeping Rock, with its veil of water, clear pool and proximity to the 'immense gulf' was one of the most popular picnic spots in the Blue Mountains, its image on thousands of postcards sent all over the world. It was better known and remarked upon than the now ubiquitous Three Sisters.

The thrill of a summer splash in 'wild' water! Ever since Louisa Meredith sought relief from the heat in a morning walk to the falls, that thrill has been shared by many; its popularity as the nineteenth century drew to a close prompting a partial domestication of the experience. Money was raised to construct a small 'bath' on Jamison Creek and today, about half way along its course, the path climbs down past evidence of dressing shed foundations and crosses the creek via a dam wall at the base of a 'gurgling and glittering' cascade, the bath's memory etched into the landscape.

Emphatic rules governed bathing, establishing times 'for ladies only' and imposing an interesting regulation that 'all using the bath after 8am shall wear a bathing dress' [15], begging the question of what, indeed, was required for an earlier swim! In later years the ranger Wilson Alcorn recalled the property of a religious sect bordering the track and walkers encountering 'naked bodies meditating in the stream'. [16] Immersion and meditation! They took no chances in their bid to commune with Nature.

While for many the track is largely a communal experience, for others it is much more personal. Just prior to reaching the Weeping Rock the creek flows beneath a large sandstone overhang. Opposite is a wooden seat offering rest and reflection to walkers, placed there almost thirty years ago in memory of a young woman who died prematurely. This is 'Effie's Seat', though most who pass would not know. They are not likely to look behind the seat at its base where, almost buried in the earth, a tiny plaque whispers in ghostly text: 'In Memory of Effie 25-8-86 A Loved Place'. There is a peace here and while the quiet modesty of her memorial stakes no claim over the ground she loved, she continues to share it with others.

Though I never knew Effie she is here every time I pass for, indeed, you could say the track has claimed her as it has Darwin himself, Louisa Meredith, the Baron and all the other wanderers (including us now living), both named and nameless, who have followed the sound of the water. Shadows in the trees, voices awakened in the rhythms of walking! 'Tread softly', advised the poet Edward Thomas in another hemisphere, 'because your way is over men's dreams…[and] there is no going so sweet as upon the old dreams of men'. [17]

Further reading

Darwin, Charles. 'A Journey to Bathurst in January, 1836' in George Mackaness, editor Fourteen Journeys over the Blue Mountains of New South Wales 1813–1841. Sydney: Horwitz-Grahame, 1965.

Meredith, Mrs Charles. Notes and Sketches of New South Wales, During a Residence in the Colony from 1839 to 1844. Sydney: Ure Smith, 1973.

Von Hugel, Baron Charles. 'Alone in a Hired Gig over the Blue Mountains to Bathurst.' New Holland Journal: November 1833–October 1834. Translated & edited by Dymphna Clark. Melbourne: MUP/Miegunyah Press, 1994.

Notes

[1] Rowland Hassall, 'Letter to Governor Macquarie', dated 18 August 1815, quoted in Hazel Magann, Ironbark and His Branches (Blacktown, NSW: The Author, nd), 44

[2] William Cox, 'Journal Kept by Mr W. Cox in Making a Road Across the Blue Mountains…', in George Mackaness, editor, Fourteen Journeys Over the Blue Mountains of New South Wales 1813–1841 (Sydney: Horwitz-Grahame, 1965), 42

[3] Charles Darwin, 'Journey Across the Blue Mountains to Bathurst in January 1836', in George Mackaness, editor, Fourteen Journeys Over the Blue Mountains of New South Wales 1813–1841 (Sydney: Horwitz-Grahame, 1965), 232

[4] Martin Thomas, The Artificial Horizon: Imagining the Blue Mountains (Melbourne: MUP, 2003), 228

[5] Eugene Stockton, editor, Blue Mountains Dreaming: The Aboriginal Heritage (Winmalee, NSW: Three Sisters, 1993), 42

[6] Jim Smith, 'History of Darwin's Walk Part 1', Blue Mountains Conservation Society Newsletter, no 79 (April 1990): 8

[7] John Hayman, 'Charles Darwin's Mitochondria,' Genetics 194 (May 2013): 21–25

[8] Charles Darwin, 'Journey Across the Blue Mountains to Bathurst in January 1836', in George Mackaness, ed. Fourteen Journeys Over the Blue Mountains of New South Wales 1813–1841 (Sydney: Horwitz-Grahame, 1965), 227–236

[9] Wendy Thorp, Archaeological Investigation, the Weatherboard Inn Site, Wentworth Fall (unpublished reported prepared for Blue Mountains City Council, April 1985). Copy held Blue Mountains Historical Society, Wentworth Falls

[10] Baron Charles Von Hugel, New Holland Journal: November 1833–October 1834, translated and edited by Dymphna Clark (Melbourne: MUP/Miegunyah Press, 1994), 332–336

[11] Mrs Charles (Louisa) Meredith, Notes and Sketches of New South Wales During a Residence in that Colony from 1839 to 1844 (Sydney: Ure Smith, 1973), 120–122

[12] Jim Smith, 'History of Darwin's Walk Part 2', Blue Mountains Conservation Society Newsletter, no 80 (July 1990): 9–10

[13] 'Charles Darwin's Visit Commemorated,' Blue Mountains Gazette, 22 January 1986, 10

[14] David Campbell, 'Devil's Rock and Other Carvings – Bower-birds' in Collected Poems (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1989), 157

[15] 'Regulations for the Management of Water Reserve No 114 at Wentworth Falls,' c1889, photocopy of public notice signed by JH Caruthers, Minister for Lands (1894–1899), in accordance with Public Trust Act of 1987; copy held by Blue Mountains Historical Society archive

[16] Quoted in 'Darwin's Walk Day', Hut News: Newsletter of the Blue Mountains Conservation Society, no 222 (February 2006): 5

[17] Edward Thomas, The South Country (London: Everyman/JM Dent, 1993), 47

.