The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

From Sheas Creek to Alexandra Canal

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

From Sheas Creek to Alexandra Canal

[media]Behind a steel mesh fence, about 250 metres southeast of the Euston Road roundabout in Alexandria, lies one of Sydney's navigational relics, the Alexandra Canal, regarded by many as Australia's most polluted stretch of waterway. While most toxic industry has moved from the area, its legacy remains; contamination on land and in water has more or less ruled out remediation and adaptive re-use of any sort. To date, the best of plans and the worthiest of civic intentions have failed, including the idea of turning the precinct into the 'Venice of Sydney'. [1]

[media]Along the length of this 4.5 km artificial waterway are a number of outfalls, channeling rainwater runoff from the suburbs of Newtown, Redfern, Erskineville, Alexandria and Zetland. A rare example of late nineteenth century coastal engineering work, the canal is one of two extant navigational canals in New South Wales and the only example specifically built to provide navigational access in industrial areas.

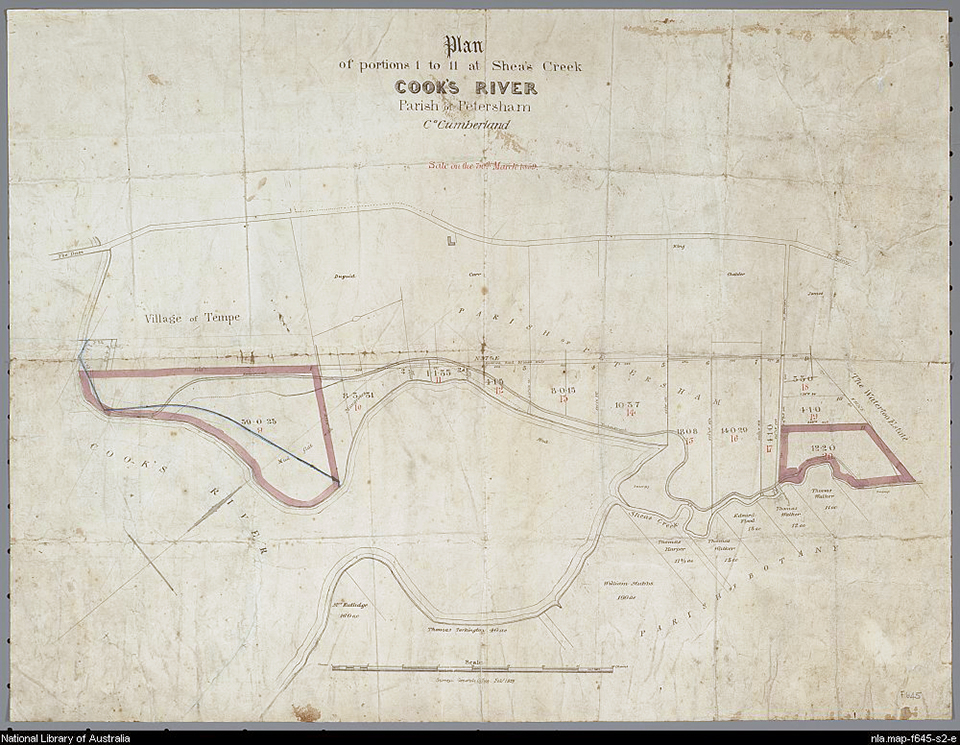

[media]Formerly known as Sheas Creek, [2] a tributary of Cooks River, the canal and its subsidiary channels flow through the suburbs of St Peters and Mascot, past Sydney Airport to the Cooks River at Tempe, before discharging into Botany Bay. The head of the canal is about 100 metres south of Huntley Street where it funnels into open concrete channels 60 metres wide, widening to about 80 metres upon reaching the Cooks River. The canal banks are formed by sloping dry sandstone starting about half a metre below water mark and capped with a sandstone coping. They are clearly visible at 1.5 metres above the high water mark. The canal's upper reaches are still very much intact, although with some localised failures of sandstone ashlar masonry. The lower reaches have been rebuilt in a variety of twentieth century materials including concrete block, shotcrete over rubble and fabricon, and range from good to poor condition. [3]

The precinct area is bounded by Burrows Road to the west, a private road to the east, Canal Road to the south and Huntley Street to the north. It also includes subsidiary channels which are part of a system radiating out to Coulson Street and Wyndham Street to the north. Four bridges span the waterway: the Shell Pipeline bridge, the Sydenham-Botany railway line, [4] Canal Road bridge (also known as Ricketty Street bridge) and a small footbridge. The canal's landmark appeal can best be viewed from the Ricketty Street bridge and Sydney Airport drive.

[media]These days there is almost no pedestrian access. Surrounded along its entire length by factories and warehouses (mostly trucking companies specialising in airfreight), there is nothing to indicate how it once might have looked. The canal, however, remains a dominant geographical feature and has strongly influenced the subdivision and land use characteristics of the southern industrial precincts.

Sheas Creek

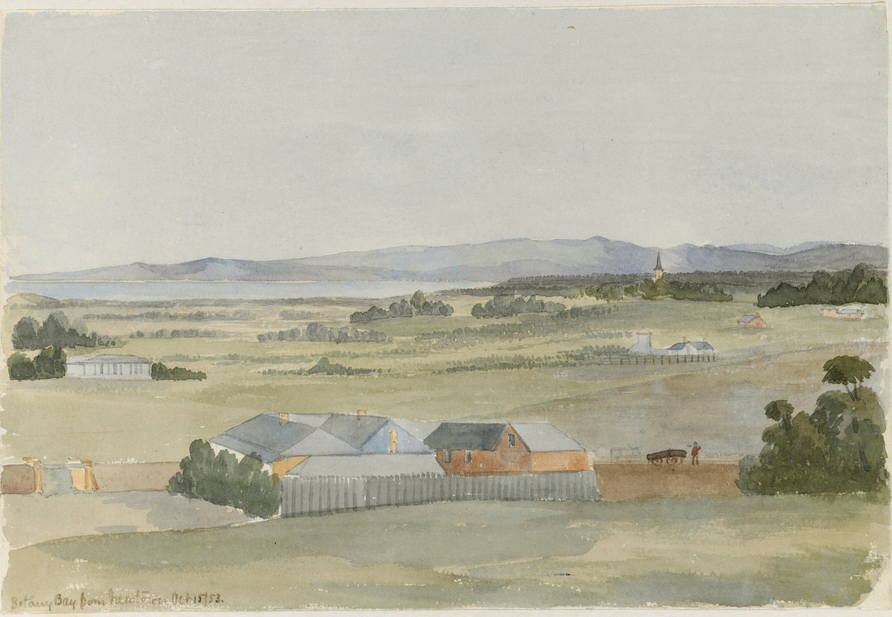

[media]In the early days of European settlement, Sheas Creek was a narrow, winding creek, part tidal, part free-flowing and fed by streams further inland. From the rise where St Peters station now stands, the view down to Sheas Creek and across Botany Bay would have been striking, but like most backwaters the creek was a breeding ground for mosquitoes. Aborigines of the time are known to have frequented this and other coastal saltwater inlets of the Cooks River and Botany Bay. Early builders fossicked through middens of discarded oyster shells which they burned to form slaked lime, a vital ingredient of mortar.

[media]In the first few decades of the nineteenth century the nearby hamlets of Newtown, St Peters, Tempe and Marrickville presented a chequered scene with gardens, grazing cattle and cultivated farms. Descriptions of the country along the Cooks River by early explorers were not optimistic about the potential for food production. Captain John Hunter and Lieutenant Bradley both mentioned the shallowness of the water and the large swamps. [5] With little hope of establishing large-scale farming close to the first settlement, the colony’s administrators were obliged to look to the rich alluvial terraces of the Parramatta and Hawkesbury rivers.

Meanwhile, in the hamlets of Newtown and St Peters competition for land intensified with the establishment of primitive clamp kilns, claypits and quarries by the brickmakers and tanneries, wool washes, chemical manufactories and other emerging industries. This was due to the Slaughter House Act of 1849 which required all noxious trades to be operated more than one mile (1.6 kilometres) from the city area. Far enough from the city not to be considered a nuisance, St Peters and its environs was close enough to supply the needs of a burgeoning metropolis. Sydney's southeast was fast becoming a thriving conurbation in its own right, with plenty of opportunities for a working family, although the stench created by industrial processes must have been truly appalling. The disposal of effluent was managed by the simple expedient of allowing waste to drain into Sheas Creek. [media]Brickmaking in particular was growing rapidly, with the establishment of dozens of small enterprises, some of which became large factories, including the Bakewell Pottery, Gentle's Bedford Brickworks and family names such as Tye, Dawes, Tuck, Standen, Speechley and Woodham, to name just a few. At the brickfields of Alexandria, Waterloo, St Peters, Newtown, Marrickville and Tempe, generations of nineteenth century brickmakers made their presence felt. Many achieved prominence as respected local citizens and representatives on municipal councils. Predictably, as the demand for housing across Sydney's eastern and inner suburbs grew, the industry boomed.

Before long, the handful of modest country homes found themselves hemmed in by rows of terrace housing, after the fashion of England's industrial towns. Eventually, the agriculturalists lost the battle, although farmyard animals were still a common sight in many of Sydney's inner city suburbs in the early twentieth century.

Depression scheme

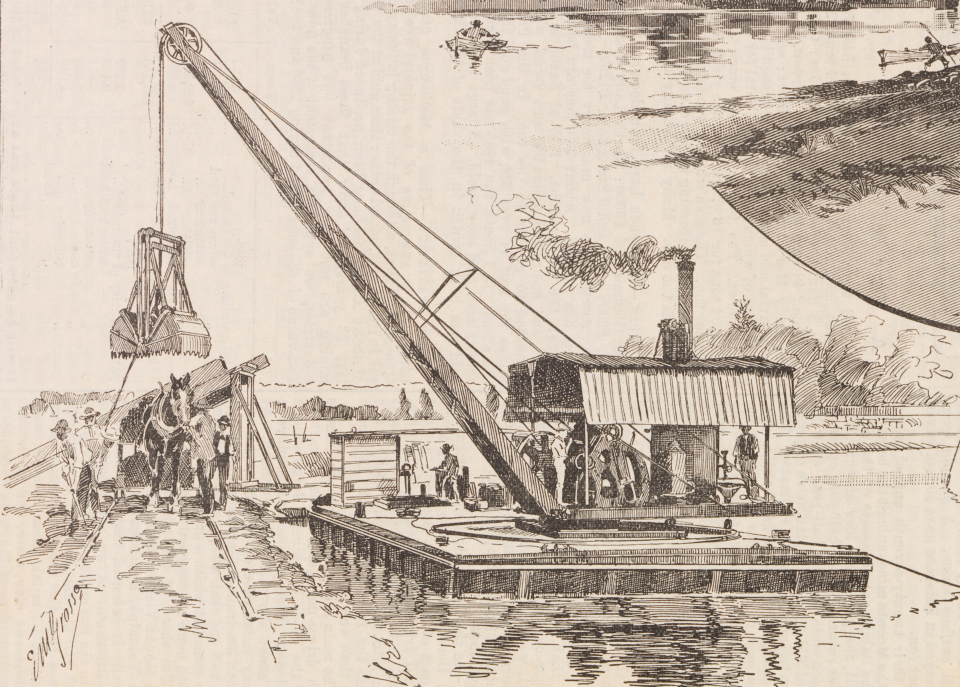

[media]With the building of the Alexandra Canal came the total reconstruction of Sheas Creek. The designer and builder was the New South Wales Department of Public Works, responsible for carrying out government plans to service industry located in the area. An impressive achievement, it was named in honour of Princess Alexandra who had married Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) in 1863. The suburb of Alexandria is also named after Princess Alexandra. The original proposal was to dig a canal from Botany Bay to Sydney Harbour large enough for barges to transport goods to boats waiting at the wharves. The ambition was to transport coal, blue metal and building materials more cheaply than could be done by rail. It would also drain swamp areas which were proving a hindrance to the extension of commercial activity in the area. Interestingly, the land on which the canal has been constructed is known to have been associated with Chinese market gardeners.

Dredging commenced in 1887 at the junction of Sheas Creek and Cooks River, southwest of the existing Sydenham-Botany railway bridge. Work continued until just after 1900, much of it performed by unemployed workers put to relief work during the 1890s depression. As often happens, the scheme was considerably reduced in scale and the canal never fully used for water carriage.

[media]Excavation work was still under way in 1896 when dugong bones, aboriginal axes and the remains of an ancient forest were discovered in the estuarine clay below the low tide level. Close examination by the then curator of the Australian Museum, Robert Etheridge, revealed the animal had been butchered by a blunt-edged cutting or chopping instrument. Two stone hatchet heads were found nearby, the artefacts providing evidence of the Aborigines who lived in the area prior to European settlement. [6] These findings have helped scientific understanding of sea level changes along the eastern seaboard and the antiquity of Aboriginal presence in the Sydney area. Almost certainly the canal bed would have contained examples of extinct flora and fauna species.

White elephant

Unfortunately, [media]the canal had more than its fair share of drownings, such as one reported in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1903:

The body of a man was discovered yesterday morning in Shea's [sic] Creek between the entrance and Ricketty Street Bridge. The discovery was reported to the Newtown police, and Constables Pigott and Andrews conveyed the body to the morgue, where it was identified as that of Stephen Anderson Briggs, aged 23, a plumber, lately residing with his wife at Alexandria. The body had apparently been in the water a couple of days.

[media]Work on the canal was finally completed during 1905 and, despite a tender being let (unsuccessfully) in the same year to extend the waterway, there was no response. In 1912, development work ceased altogether. So what went wrong? Soon after its completion in 1900, the canal began to silt up, which required continuous dredging. It also needed to be kept in a constant state of repair. [media]More significant, perhaps, was the shallow draft of the canal which rendered it useless to larger vessels. Tidal flows also meant that careful timing was needed to avoid being stranded. These factors all contributed to poor patronage by industry, so that with little income being generated the canal soon became a 'white elephant'. [media]During World War II, 250 wool sheds were constructed along the eastern side of the canal, built as temporary storage for the stockpiled wool. [7] At the same time, the wharves were demolished. Some of these sheds still exist today, although they are in poor condition.

Redevelopment proposals

[media]Community interest in the canal encouraged South Sydney Council to publish a refurbishment plan in July 1997. In part this was due to the gradual transformation of large parts of Sydney's industrial southeast into a residential quarter. The council determined that any development adjacent to or on the canal itself should involve the least possible physical intervention to its fabric and take into account the heritage significance of the canal. The following year Sydney Water, the owner of the canal, launched a $4 million plan to clean and restore the condition of the water; this plan was subsequently abandoned. In June 1998 the state’s Minister for Urban Affairs and Planning announced that architecture students from the University of New South Wales would be commissioned to create designs that would transform Alexandra Canal into a 'stunning water and green recreation corridor between Sydney Harbour and Botany Bay'. The students were given a $5,000 grant, funded by the South Sydney Development Corporation, [8] an authority owned by the state government to oversee the redevelopment of the Green Square precinct.

By August 1999, a $300 million plan was announced by the South Sydney Development Corporation that would feature housing for 25,000 residents, cafes, restaurants and boating facilities on the Alexandra Canal. In 2001 the Deputy Premier, Planning Minister and Member for Marrickville, proposed an Alexandra Canal Masterplan, intended to transform the canal into the 'Venice of Sydney'. [9] A grand cycleway was planned for the canal banks. Unfortunately, by 2008 it had all become too much, due to the cost of remediating the waterway and land sites.

[media]It was perhaps just as well, because a report published by the New South Wales Environment Protection Authority (EPA) on 26 April 2008 described the canal as 'the most severely contaminated canal in the southern hemisphere', warning that 'the sediments are toxic’. The 'do-not-disturb' action was justified because any dredging would have increased the risk; deeper sediments are generally more contaminated than upper layers.

In recent years there have been further setbacks. In 2011 a plan came to light for coal seam gas exploration and mining adjacent to the canal on vacant industrial land, the first such scheme within Sydney metropolitan area since the 1890s coal mining proposal at Taronga Park and the mining of coal from Balmain.

One day the dream of remediating and extending the Alexandra Canal to form a major recreational, ecological and visual water asset within a regional green corridor system might be realised, but for the time being it remains precisely that: a dream.

Notes

[1] 'Promise of Little Venice washed away', The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 April 2008

[2] Sheas Creek was named after Captain John Shea of the First Fleet. He is credited with being the first white man to shoot a kangaroo; he died of tuberculosis on 2 February 1789, making him the first officer to die in the colony. Alexandria Council's book, 1868–1943 Alexandria: The Birmingham of Australia, 15 Years of Progress, Sydney, 1944, pp 52–55, has a chapter 'Alexandra or Shea's Creek Canal' and includes a striking drawing of the canal in the 1940s

[3] The south-western walling of the canal beyond the Shell bridge is rendered rubble walling. The south-eastern face is rendered rubble walling almost to the railway bridge. These alterations to original fabric reflect alterations to the course of the canal near its junction with the Cooks River during the three phases of airport expansion. 'Heritage item, Number 4571712, Current name: Alexandra Canal 89AZ', SydneyWater website, http://www.sydneywater.com.au/SW/water-the-environment/what-we-re-doing/Heritage-search/heritage-detail/index.htm?heritageid=4571712&FromPage=searchresults, viewed 8 February 2013

[4] The Sydenham to Botany railway bridge over the canal had the first lifting span used in a railway bridge in Australia, 'Heritage item, Number 4571712, Current name: Alexandra Canal 89AZ', SydneyWater website, http://www.sydneywater.com.au/SW/water-the-environment/what-we-re-doing/Heritage-search/heritage-detail/index.htm?heritageid=4571712&FromPage=searchresults, viewed 8 February 2013

[5] 'Cooks River', Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cooks_River, viewed 8 February 2013

[6] 'A submerged forest', Singleton Argus, Saturday, 8 August 1896

[7] One of the old wool storage sheds (no 67) housed government records from 1954 to 1984. This was prior to the opening of the records centre at Kingswood. Richard Blair, President of Marrickville Heritage Society, recalls records being deposited there early in his career as a state public servant. Interview with Richard Blair, President of Marrickville Heritage Society Inc, 8 February 2013, Sydney

[8] Paola Totaro, 'Fetid drain to become a clean, green corridor', The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 June 1998, p 8

[9] 'Promise of Little Venice washed away', The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 April 2008

.