The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Smallpox epidemic 1881

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Smallpox epidemic 1881–82

At 2.50am on 29 April 1881, the steamship Brisbane under the command of Captain J Beddell, arrived in Port Jackson from Hong Kong. The journey had taken just over three weeks. On board were 106 Chinese men in steerage, plus cargo which included oil, preserves, tea, cigars, opium and rolls of matting.

The Brisbane proceeded to North Head, the site of Sydney's quarantine station, with a case of smallpox on board. The smallpox victim and several other men were transferred to the hospital ship Faraway, while the remainder stayed on board the Brisbane until the captain was granted pratique (health clearance) by the quarantine health officer some weeks later.

Smallpox spreads

[media]On 25 May, three weeks after the Brisbane's arrival, Dr Haynes G Alleyne, chief health officer and head of Sydney's quarantine service, was notified of a possible case of smallpox. The infant daughter of On Chong, a Chinese merchant from Lower George Street, had come down with fever and a rash, prompting a call to a local doctor.

Dr Alleyne sent one of his government medical officers to examine the child. As it turned out, there was no clear diagnosis, so the decision was made for the medical officer to monitor the child on a daily basis.

Sydney newspapers soon heard of the case and began asking why the government medical officer was allowed to move freely about the city when he made daily visits to On Chong's place. If the infant's case turned out to be smallpox, the doctor could well be spreading the disease. The papers also wanted to know why the premises weren't under quarantine.

Quarantine begins

Despite the pressure, another week passed before the decision was made to place a barricade around On Chong's store and the adjacent buildings. Dr Foucart, who'd been visiting the child, was also placed under quarantine and ordered to remain with the On Chong child. A police guard was mounted outside the premises to make sure no one came or went.

In the following week there was growing unease, as fear and suspicion began to take hold. Despite the clamouring in the papers, Dr Alleyne and his medical colleagues were either unwilling or unable to say if the On Chong case was smallpox or not. Nevertheless, local doctors were on the alert for signs of a disease that few had dealt with, a disease that in its mildest form could be mistaken for chickenpox or some other infection.

Australia's distance from Europe and Asia had kept the colonies relatively free from smallpox in the preceding decades – that, plus an effective quarantine policy where ships arriving with disease on board were isolated at North Head. But as ships made the transition from sail to steam, travel times were reduced by as much as half. This meant that diseases such as smallpox, with a two- to three-week incubation period, began to slip through the quarantine net.

This is what had happened five years earlier, in 1876, when the Holden family from The Rocks was infected with smallpox from an unknown source. Once the disease was diagnosed, the authorities didn't waste any time but removed the family to the quarantine station. Several members of the family died, but the disease was effectively contained by quick diagnosis and isolation. The use of the quarantine station in this instance set a precedent: up to this point, it had only been used for passengers and crew on arrival in Sydney.

Surry Hills outbreak

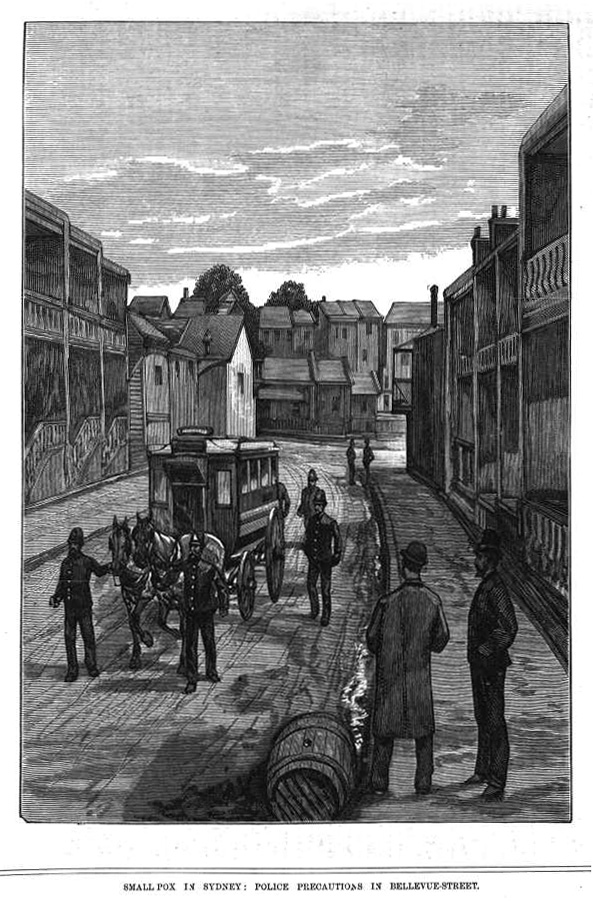

[media]Three weeks after the On Chong case was notified for investigation, Dr Michael Clune from College Street, near Hyde Park, was asked to visit Edward Rout who lived nearby in Surry Hills. From the description Clune suspected smallpox.

Next morning, Tuesday 24 June, he went to the terrace in Bellevue Street where Rout and his wife ran a lodging house. Clune was met at the door by Mrs Rout who led him upstairs to a tiny attic. As they climbed the narrow stairs Clune was almost overcome by the fetid smell, one he recognised from his training in Dublin. He didn't go inside the attic but stood in the doorway. There by the light of a hand-held lamp he could see Edward Rout's half-naked body. It was covered with pustules. The man was clearly dying from smallpox in its most virulent form. There was little Clune could do for him.

As they made their way back down the stairs, Clune established from Mrs Rout that her husband had been working on the roof of premises opposite the On Chong place for several weeks before falling ill. In addition to Mr and Mrs Rout and their children, there were two other families in the house, a total of fourteen people in all. Half a dozen of them were children who attended three different schools.

There was no time to waste. From Bellevue Street, Dr Clune went to the city to see Dr Alleyne. Later on that afternoon a medical officer was sent with Clune to confirm that the case was smallpox and the house was placed under quarantine.

Spread in The Rocks

[media]That same day, another case was reported to Dr Alleyne. This time it was in The Rocks, several blocks from On Chong's store. The house was owned by a man named Keats and was also run as a lodging house. The patient – one of Keats's lodgers – had been moved by her husband to a draughty cellar so as not to place other residents at risk. As had happened with the On Chong child, this case also was not clear-cut, but in the circumstances the house was quarantined anyway.

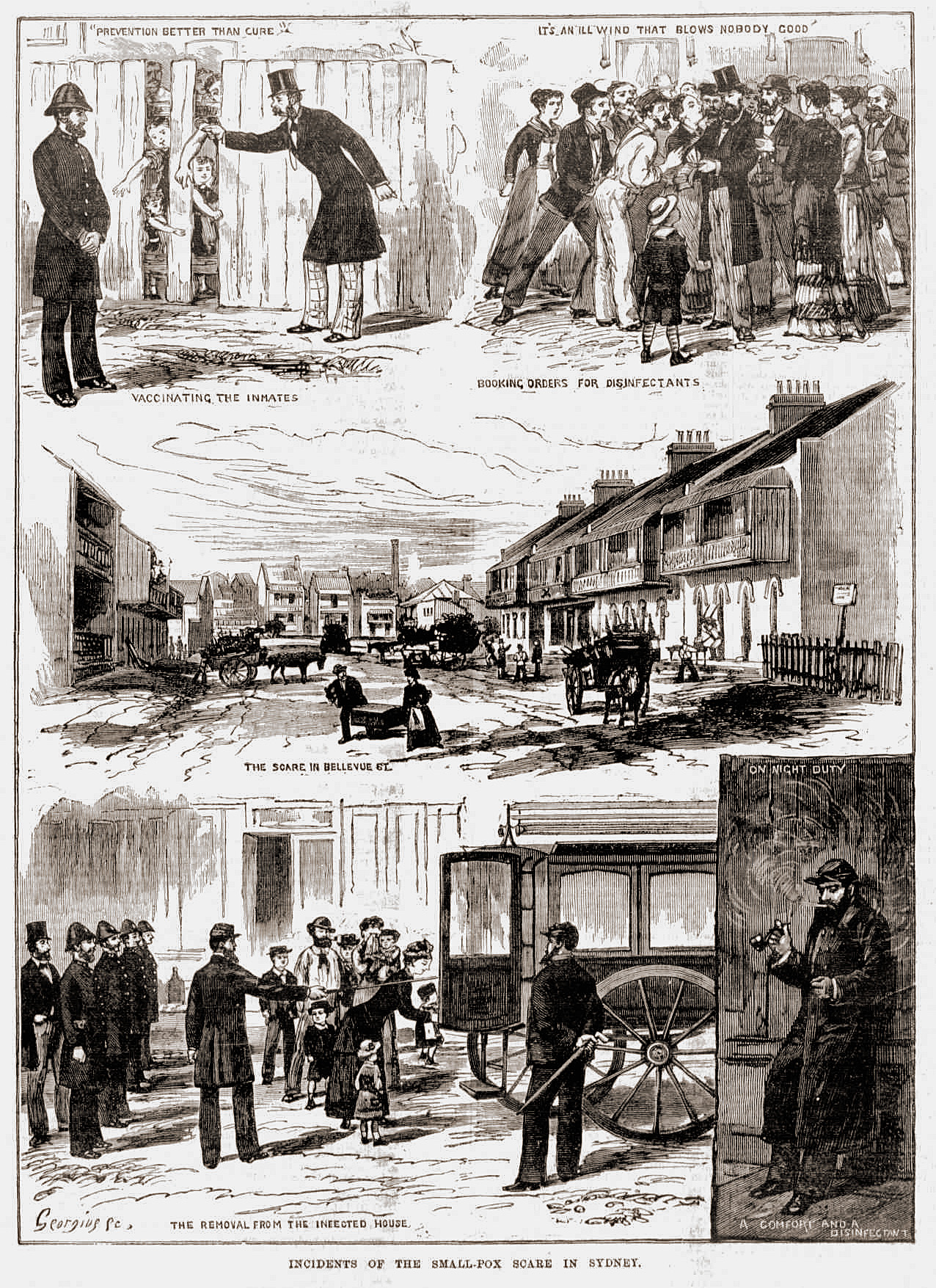

Next day, Wednesday 15 June, a medical officer was dispatched to vaccinate occupants of Edward Rout's household. Rather than go inside the house, the doctor had everyone go out the back where he would be waiting in the back lane. There, one by one, they each placed an arm through a hole in the paling fence, while the doctor who stood in the lane outside administered 'the scratch' (smallpox vaccination).

Throughout the day, Dr Clune and his colleagues were kept busy with a steady stream of patients concerned that they might be infected with smallpox. One of the men who came to see Clune was John Hughes, from Underwood Street near Circular Quay. Hughes had several large sores on his neck, but Clune was almost certain it wasn't smallpox. Nevertheless he undertook to send someone else to check on Hughes at his home later on. Hughes went home and waited for the call, but by evening still no doctor had visited. Instead, he found to his chagrin that his house had been barricaded by police, and a police guard mounted round the clock.

Throughout the day, police had received hundreds of reports from people who harboured suspicions of their neighbours or associates. One case involved several Chinese men who'd been spotted arriving at a vacant warehouse in Botany Road, Waterloo, just after dark. They were seen carrying a bundle inside which looked suspiciously like a body.

When the police went to the warehouse, they found the men had locked themselves in an upstairs room. One man was suffering from what looked like smallpox. The government medical officer was sent for and the warehouse placed under quarantine.

Into quarantine at North Head

Next day, with several cases confirmed and who knew how many people infected, the government finally swung into action. At a meeting of leading government officials held at the Treasury Department that morning, a plan was drawn up to contain the disease. Once again the decision was made to make use of the quarantine station to isolate victims and their household contacts. It was decided to purchase a horse-drawn omnibus to transport victims to Cowper's Wharf, where they would be taken by steamboat across the harbour to North Head. The small steamer Pinafore was hired for this purpose.

The first boatload left that same afternoon, made up of close contacts of known and suspected cases. They were offloaded at the quarantine station and taken to the hospital enclosure located on the hilltop above Spring Cove. There they would spend a miserable night without food or comfort of any kind. Amongst them were Edward Rout's four children, plus John Hughes's wife and their six children, as well as several other families.

Meanwhile back in Surry Hills, Mrs Rout had stayed behind with her husband. He died around three in the afternoon. For hours, she waited for a doctor to come and certify the cause of death, but no one came. Several gravediggers eventually arrived on the omnibus with a coffin in tow and took Mrs Rout and her husband's body down to Cowper's Wharf. Once there, they refused to unload the coffin until the undertaker kept his promise of a bottle of brandy to see them through. Only then did they take the coffin to the longboat which would be towed behind the Pinafore.

Among those on the wharf that night was Won Ping, the smallpox victim who'd been discovered in the Waterloo warehouse, along with three other men. John Hughes, the man who'd been to see Clune, was also there. The men were placed in the engine room of the steamer, away from other passengers.

The last two passengers to arrive at the wharf late that night in the pouring rain were doctors Clune and Caffyn (the latter a government medical officer). Both had been in contact with smallpox victims, and had been ordered into quarantine by Dr Alleyne. The circumstances of their incarceration were not made clear, but they were needed to take care of the smallpox victims. Alleyne knew how difficult it was to get doctors to work at the quarantine station, such was its reputation.

Dr Caffyn was on the government payroll and no doubt understood he'd be paid, but for Clune it was a different matter. He relied on his general practice to support his wife and six-year-old daughter. Nothing had been said to him about any form of recompense. Not surprisingly he objected and tried to speak to Dr Alleyne but the chief health officer refused to see him, instead threatening Clune with arrest if he continued to refuse to go. Clune packed his trunks and went to the wharf, after vowing to his wife that he'd soon be back.

As the Pinafore was prepared for departure, the doctors were shown to the tiny cabin where they were seated alongside Mrs Rout. In the longboat the gravediggers sat astride the coffin, passing a bottle of brandy between them as they set off into the cold wet night.

It was well after midnight by the time the Pinafore arrived at Spring Cove. Since no one was waiting at the jetty, the passengers had to wait on board while one of the crew went to fetch the superintendent, a man named Carroll. When he arrived a half hour later, he took the doctors and Mrs Rout up the steep pathway to the hospital grounds. There he showed Mrs Rout to the pavilion where she was reunited with her children and the others who'd arrived that afternoon.

Carroll then took Clune and Caffyn to a cottage used by medical staff, before taking them back down to fetch some bedding. By the time they got back to the cottage, the blankets were wet so they slept fully clothed.

Meanwhile the captain of the Pinafore took Hughes, Won Ping and the others to the Faraway, anchored in Spring Cove. There they would be kept in isolation under the care of a man named Walsh.

As for the body of Edward Rout, which was supposed to be buried without delay, the gravediggers had passed out on the beach. It was just before daylight when the two men were kicked awake by the superintendent who sent them up to the burial ground. There they used a broken shovel to dig the grave and dispose of the body.

Public outrage

So began a terrible saga for those who were sent to the quarantine station that night and in the months that followed. The smallpox victims and their families, as well as the doctors sent to attend them, were treated with the utmost contempt by the superintendent of the quarantine station. They and the dozens of others who joined them were denied such basics as clean towels, linen and medical supplies, by a man who was totally unprepared for the task of managing such a situation.

Such was the level of public outrage, when eventually the stories began to leak out, that a Royal Commission was set up to enquire into the management of the quarantine station. Carroll was suspended and never reinstated, but, as the Royal Commission revealed, the fault really lay with Dr Alleyne, who left the superintendent in charge knowing he was ill-equipped for the task.

The result was that those in quarantine – especially those on the Faraway and Dr Clune in the hospital enclosure – suffered terribly over the next few months. For Hughes the irony was that he may not even have been infected with smallpox. Sadly, he lost his youngest daughter who contracted smallpox from inoculation which took place at the quarantine station using lymph from one of Rout's children. As for Clune, he continued to believe he would be returned to Sydney. Eventually despite his constant appeals by telegram to anyone he could think of in Sydney, he suffered a physical and mental breakdown and had to be replaced.

What went wrong?

On the surface, the plan of action to contain the epidemic was fairly sound and did achieve the desired result in preventing the spread of the disease in Sydney. The plan relied chiefly on swift isolation of smallpox victims and their contacts, and vaccination of those exposed to the victims. But there were several major flaws in the planning.

The first was the lack of adequate management of the quarantine station. What was really needed was a medical superintendent with an understanding of infection control, and basic necessities for treating the sick. Instead clean sheets and towels were withheld, as was soap and medical supplies. This transpired despite a government edict that those affected should have everything they needed by way of food, clothing and medical care.

The next problem was a lack of cowpox lymph needed for vaccination. This wouldn't have been so much of a problem had more Sydney residents been vaccinated before the disease broke out. As it turned out, only one in five had any kind of vaccination. In the event, the shortfall in lymph meant many were inoculated arm-to-arm, a procedure which involved some risk. Not only could the recipient be infected with smallpox but other diseases could be passed on as well. It was by no means the most desirable method.

The issue of vaccination itself was as hotly debated then as now. There were those who believed that vaccination led to all kinds of terrible ills. Yet there was plenty of evidence from Britain and elsewhere that effective smallpox vaccination protected those who were exposed. Even if they contracted the disease it inevitably took a milder course, and fatalities from the disease were prevented.

Another hotly debated issue was the question of Chinese immigration. The fact that the first case was a Chinese child gave the anti-immigration lobby the fuel they need to push through legislation restricting Chinese immigration. Local Chinese were vilified from day one of the epidemic – they were spat on and abused in the streets and on public transport, their dwellings were inspected on a regular basis, and they underwent enforced vaccination. This was despite the fact that smallpox was also rife in England and Europe at the time, and could just as easily have come from there.

In fact by the end of the epidemic there were only three Chinese smallpox victims – the On Chong child and two men.

Public health

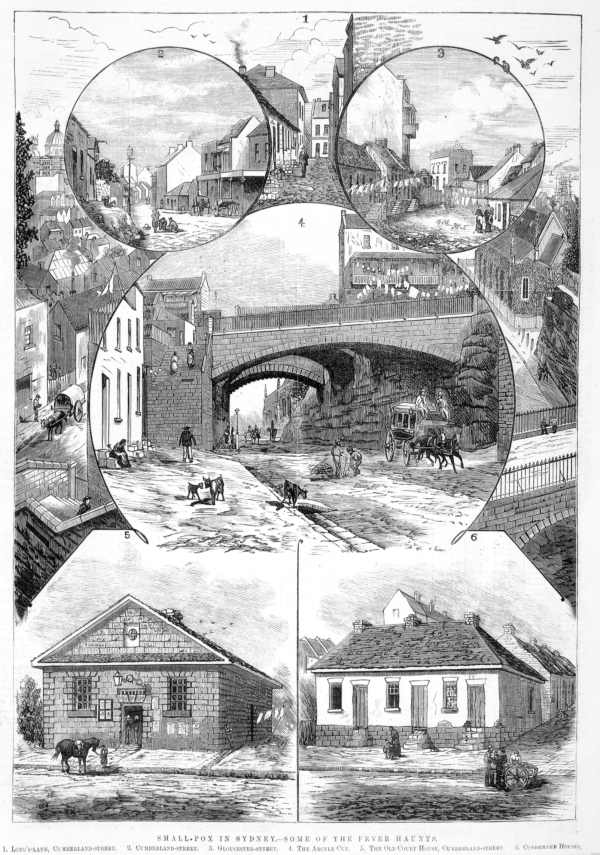

[media]On the positive side, the epidemic led to major changes in health administration. The first board of health – with representatives of local government, health, police and treasury –was set up in response to the epidemic. The board had powers to handle matters affecting public health including sanitation and living conditions. Its mandate was to administer the Infectious Diseases Supervision Act of 1881, which introduced compulsory notification of smallpox and other infectious diseases.

Another much-needed development was the establishment of a dedicated ambulance service, with personnel trained in infection control.

A hospital for infectious diseases was set up at Little Bay, in Sydney's south, even as the epidemic progressed. The first smallpox patients were admitted to the rudimentary hospital in early 1882 at the tail end of the epidemic. Known eventually as the Coast Hospital, and later as Prince Henry Hospital, it would serve Sydney residents for more than a century until its closure in 1988.

As a result of the Royal Commission into the management of the quarantine station, the facility underwent a revamp and a medical superintendent was appointed. The hospital ship Faraway was taken to Morts Works in Balmain and fully refitted as a hospital, with two wards catering for 100 patients.

In terms of the number of people infected, the smallpox outbreak of 1881 was by no means a major epidemic. In the nine months from May 1881 to February 1882, 154 cases were notified to the authorities. Of these there were 40 deaths. Yet the way that the epidemic unfolded and the impact it had on the lives of those who were caught up in the early days of the outbreak lent it greater significance than the numbers suggest. It would have been difficult at the time to find someone in Sydney who was unaffected by fear of contagion and the resulting upheaval.

The case which sparked the epidemic in the first place was never discovered, though several theories have since been proposed. The strongest is that the young nursemaid who was employed to care for the On Chong child had a mild case of smallpox which she passed on. But the question of how the nurse was infected remains unanswered to this day.

References

Raelene Allen , 'Smallpox in Sydney', MA thesis, UTS, 2006