The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Bray, James Samuel

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Bray, James Samuel

[media]A local character for nearly 50 years, James Samuel Bray was an amateur naturalist, prolific author and erratic entrepreneur in late-colonial Sydney. Through his ceaseless exploration of the city's hinterland, Bray captured the dwindling traces of its natural, Indigenous and early settler heritage. During the 1880s and 1890s, Bray's Museum of Curios traded in relics, specimens and information, connecting visitors to Sydney with his contacts across New South Wales. Despite representing the colony at exhibitions as far afield as Melbourne, Philadelphia and Calcutta, Bray perennially skirted the edges of scientific and social respectability. Often ostracised in life, and soon forgotten after his death, he nevertheless embodied the 'antiquarian imagination' that took root in the Australian colonies from the 1870s until World War I.[1]

Unnatural history

[media]Sydney was on the verge of transformation when Bray was born in Bent Street on 9 January 1849. His father – also James Samuel Bray – was an English 'oil and colour man' who arrived in the colony in 1840. His Pitt Street painting and decorating business proved modestly successful through the gold-fuelled expansion of the 1850s. Marrying locally born Amelia Hudson in 1845, the couple had five children and in the mid-1860s purchased Camden Villa, a solid house still standing at Milsons Point. [2]

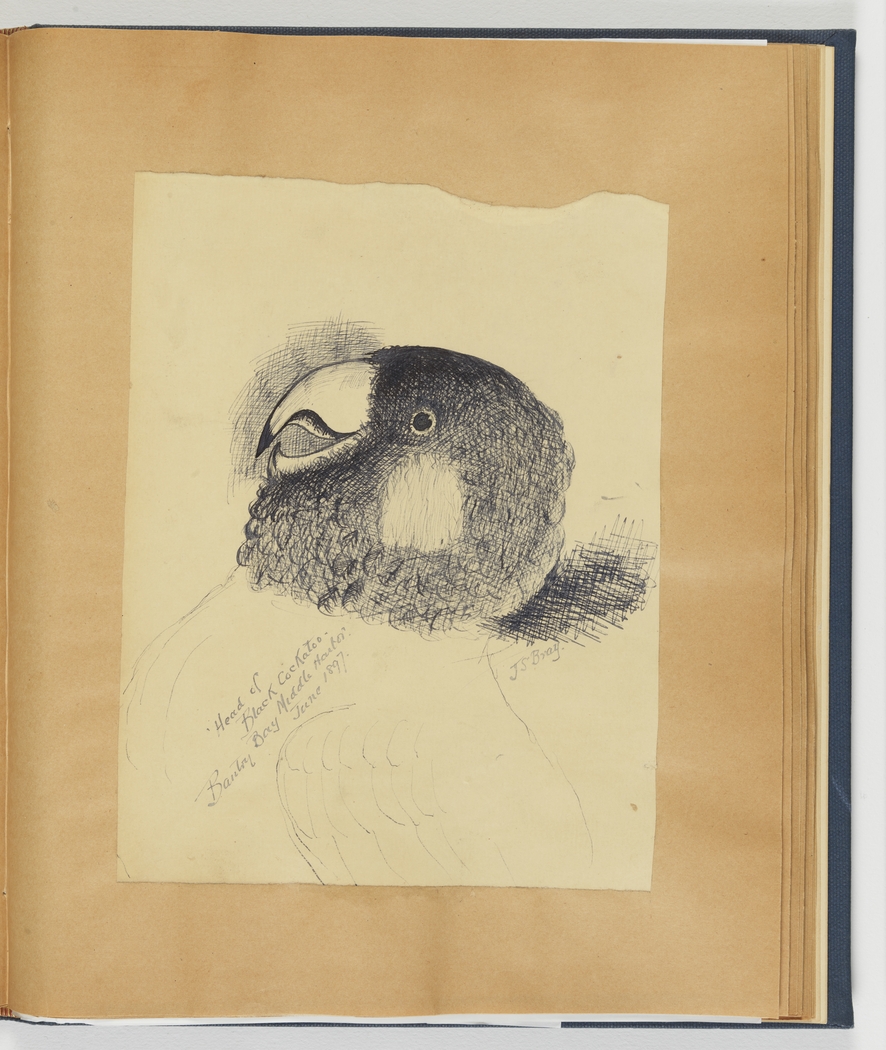

Young James clearly relished exploring the city’s north shore, which in the 1860s remained only partly developed. As documented in articles he wrote for the St Leonards Recorder, wildlife continued to flourish around Middle Harbour into the 1870s but was visibly receding before urban expansion.[3] In his typically ambiguous fashion, Bray lamented this loss of animal habitats while at the same time boasting about his destructive methods for securing interesting bird specimens.[4]

[media]In fact, as young as age 11 'Master James Bray' had presented the 'Nest and egg of a wren' to the Australian Museum.[5] The museum's director, Gerard Krefft, apparently fostered Bray's early fascination with natural history, earning his enduring loyalty. After Krefft was controversially dismissed from the museum in 1874, Bray remained close to the family, later coordinating a public subscription to bolster their faltering finances. A poignant note written in 1881 by Gerard's wife, Annie, is telling: 'Dear Mr Bray, Mr Krefft is dead. Come if you can'.[6]

Unorthodox relationships

[media]Bray's own family circumstances were far from orthodox. In 1870, a year after his father's death, he married Janet Muston, daughter of a large and upright north shore family. As she was noticeably pregnant, the wedding – and the birth of their first two children, Emily and John – occurred in rural Armidale. They returned to Sydney in 1872 where two years later Bray's mother suffered an episode of 'suicidal melancholia' and hanged herself at Bay View House private asylum in Tempe.[7]

In 1875 Bray's son John also died, aged just 3. Barely two months later, Bray deserted Janet, Emily and 2-year-old Arthur. He then took up with Fanny Drake, a barmaid recently arrived from England. Janet pursued him for maintenance, leading to Bray's arrest in March 1876. A notice in the Police Gazette provides some indication of his appearance and habits:

5 feet 6 inches [168 cm] high, light brown hair, Dundreary whiskers and moustache, sallow complexion; dressed in light brown tweed suit, and black low-crowned felt hat; frequents the Theatres. He is likely to leave for Cook Town.[8]

[media]Bray indeed found it convenient to go voyaging in Venezuela in late 1876. A year later Fanny gave birth to the first of their four children, Mildred 'Desda' Drake. A second daughter, Alma, also bore Fanny's surname. It was only when she was large with their third child, Boronia, that Bray married her in 1883, by which time Janet Bray had been dead for nearly 5 years. Bray's second family was completed by James, born in 1890 and graced with the middle name Buprestis, after a colourful genus of beetles.

Insatiable curiosity

Bray's business career was similarly erratic. Until resigning after his arrest in 1876, he had been the senior-most clerk in the colony's Telegraph Department, earning £200 per annum.[9] After a period with the Australian Mutual Fire Company, Bray spasmodically traded book-keeping skills for rent, but rarely balanced his own finances.

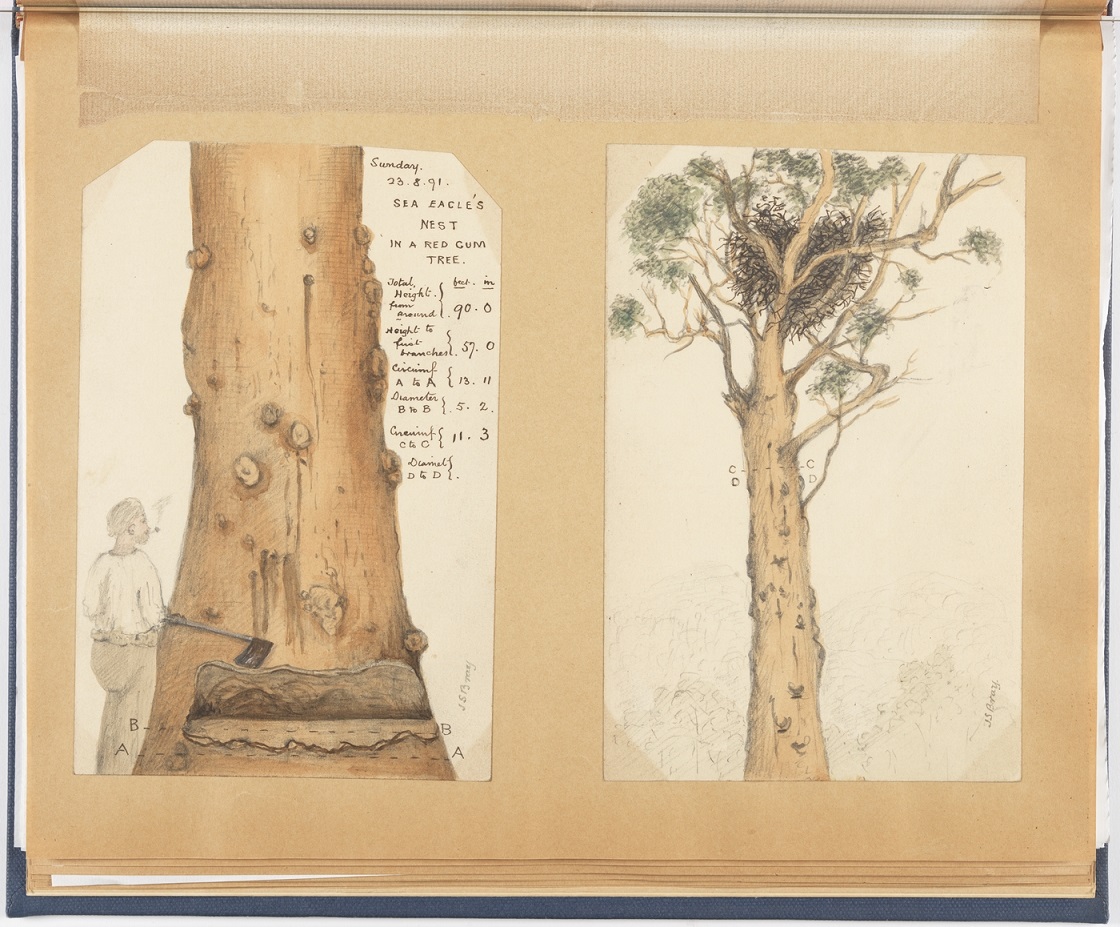

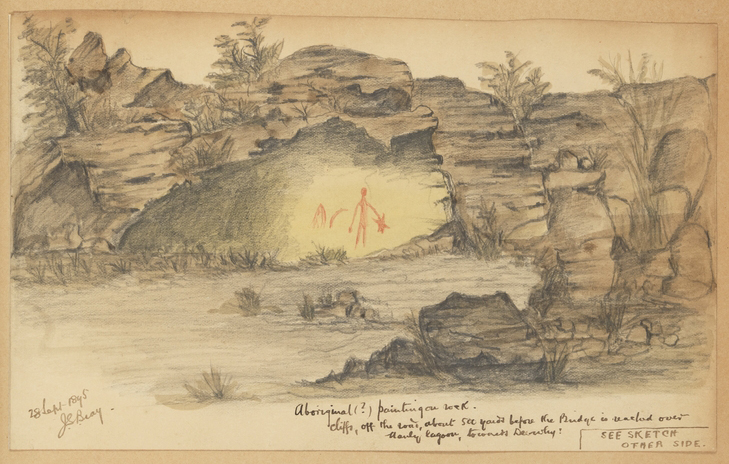

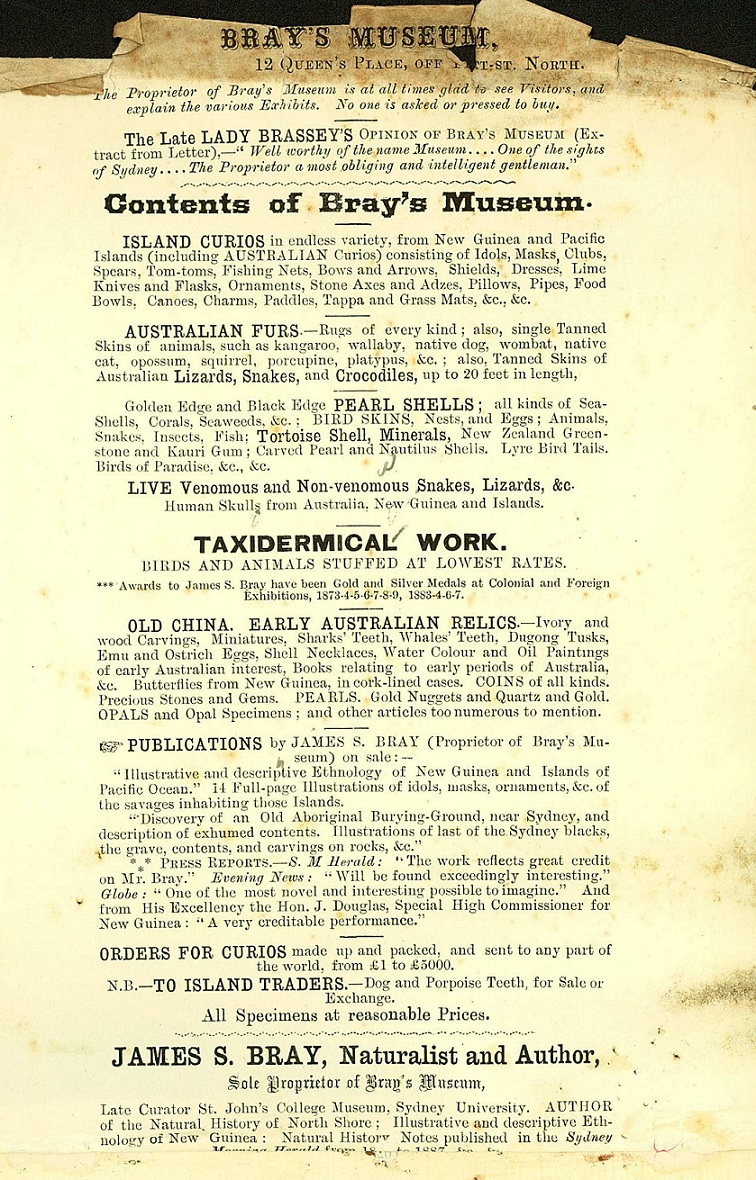

[media]Clerical work, nevertheless, was merely Bray's job. His vocation was an insatiable curiosity about the natural world and what he viewed as the 'vanishing races' of the southern Pacific. From the mid-1870s, Bray endlessly explored remnant bushland and Indigenous sites on the fringes of Sydney. Middle Harbour and Manly were his favoured locales and the colony's booming print market proved eager to publish his reports. Although he found few takers for his planned account of Aboriginal rock art and burial sites,[10] in 1887 Bray issued an illustrated booklet documenting his specimens of 'ethnology' drawn from numerous Pacific cultures.[11]

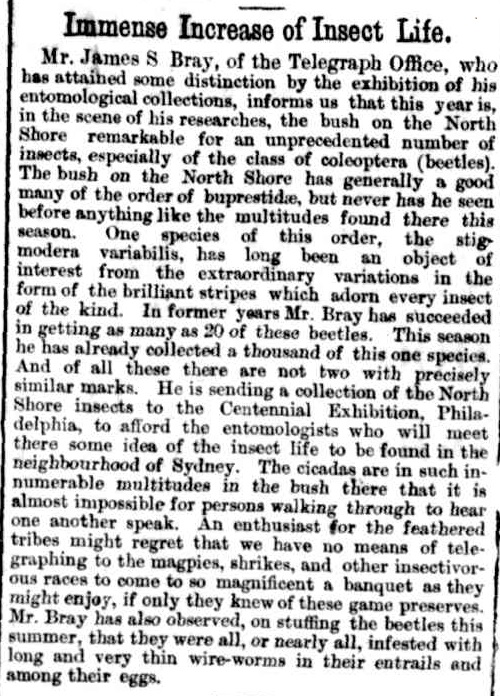

[media]He was, moreover, a talented nature writer, shaping an evocative sense of place and capturing the habits of the many creatures he pursued. Most of them, unfortunately, fell victim to his gun and specimen jar. As early as 1873 Bray had begun creating taxidermy displays for intercolonial exhibitions. Having exhibited at Sydney's Garden Palace in 1879, his extravaganza of 150 stuffed birds at the 1880 Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition rated 'special mention'.[12] Bray's work regularly won prizes, including a gold medal for timber samples gracing the New South Wales stand at the Calcutta International Exhibition of 1883–84.[13] Perhaps a high point in his quest for scientific recognition, this major event also showcased Bray's mounted birds and a dozen Australian animals, including two koalas, 'the young one just having left its mother's pouch for good'.[14]

Launching Bray's Museum of Curios

Perhaps this record of success emboldened Bray to launch his own 'museum'. Certainly, after Krefft's departure, Bray's presence, correspondence and specimens were rarely welcomed at the Australian Museum.[15] Conversely, by 1881 his Garden Palace display of 'nearly all the varieties of Australian birds' comprised the 'principal show-case' in the small museum at St John's College within the University of Sydney.[16]

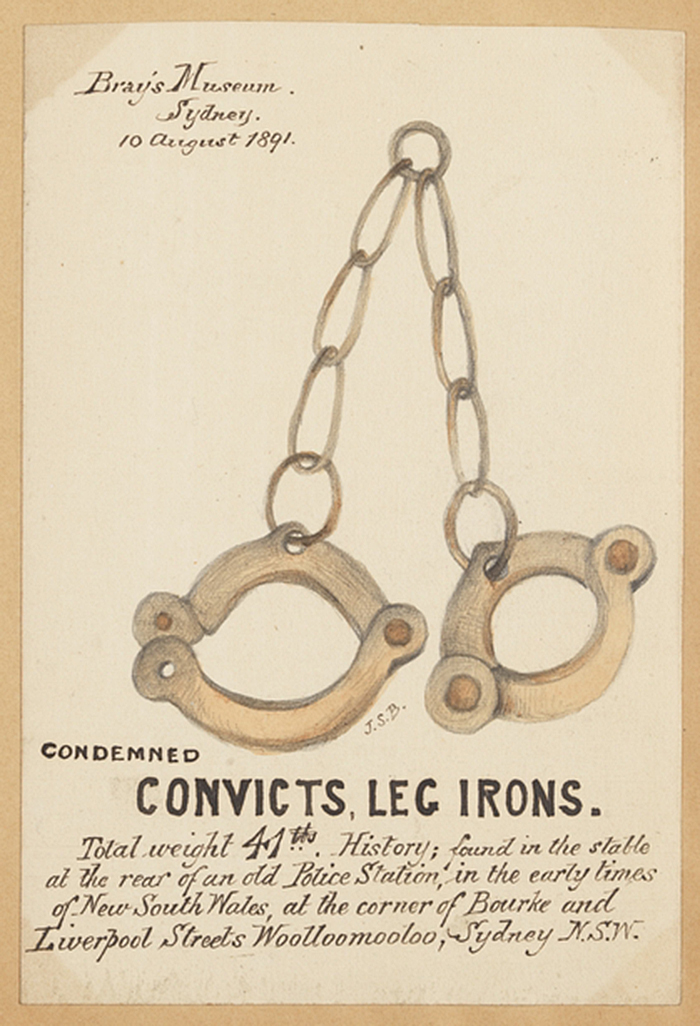

[media]In mid-1884, he transformed his home at 84 Forbes Street, Woolloomooloo, into 'Bray's Museum of Curiosities, Art Objects, Paintings, Books, Carvings, Natural History, &c'. Bray hoped not only to compete with established taxidermy businesses such as Tost & Rohu but to trade on a growing colonial fondness for relics of the early days of white settlement, from coins to convict chains.[17] Without the social or financial means of colonial antiquarians such as David Scott Mitchell, however, Bray's collection remained modest, if 'interesting'.[18] His success can be judged by the arrival of the bailiffs barely a year later. When Bray declared himself insolvent in February 1886, he valued his museum stock at £147. At auction it raised less than £34.[19]

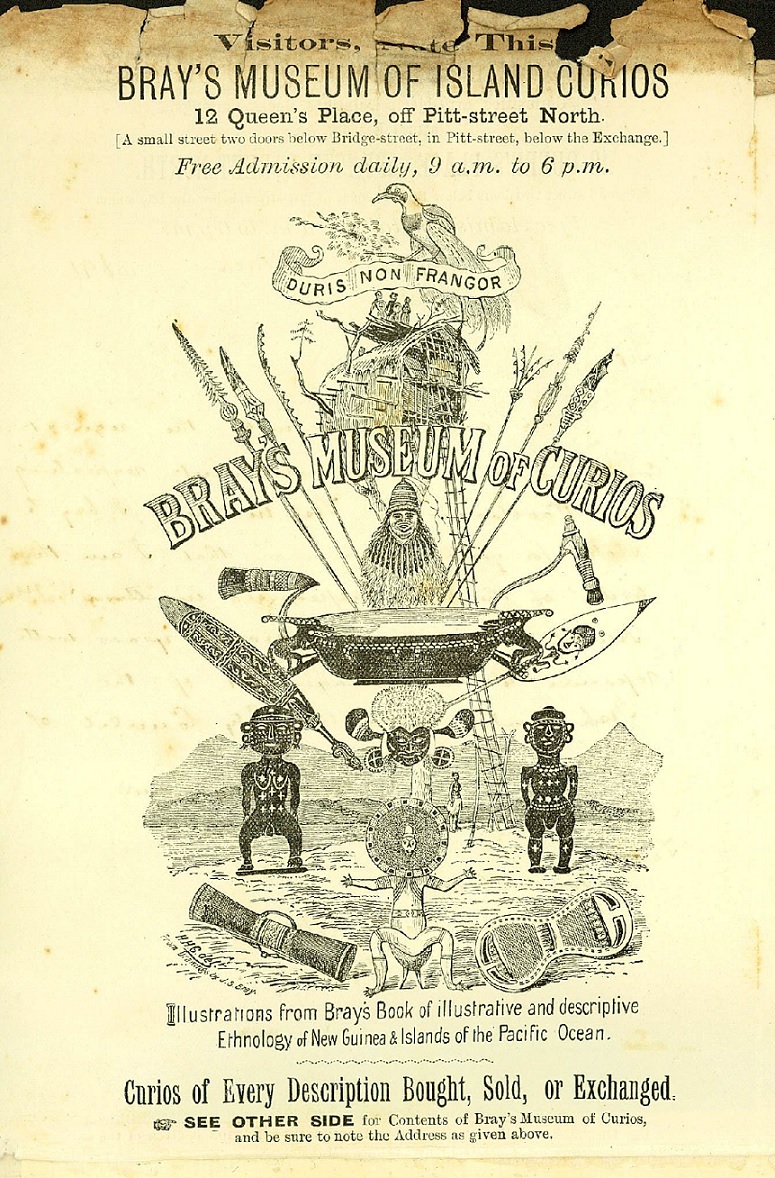

[media][media]The insolvency case was barely settled before a new 'Bray's Museum of Curios' opened in late 1886. Located at 12 Queen's Place, now Dalley Street, it comprised a three-roomed shop within a series of single-storey premises known as the Canada Buildings. Linking George and Pitt streets, and just a block back from Circular Quay, it was well placed to attract ferry passengers, passing sailors, international tourists and the neighbourhood's energetic drinkers. Here, Bray boasted, patrons could inspect – and purchase – Australian furs, shells, gems, paintings and colonial relics, plus 'island curios in endless variety' and 'human skulls from Australia, New Guinea and Islands'.[20]

Snakes alive

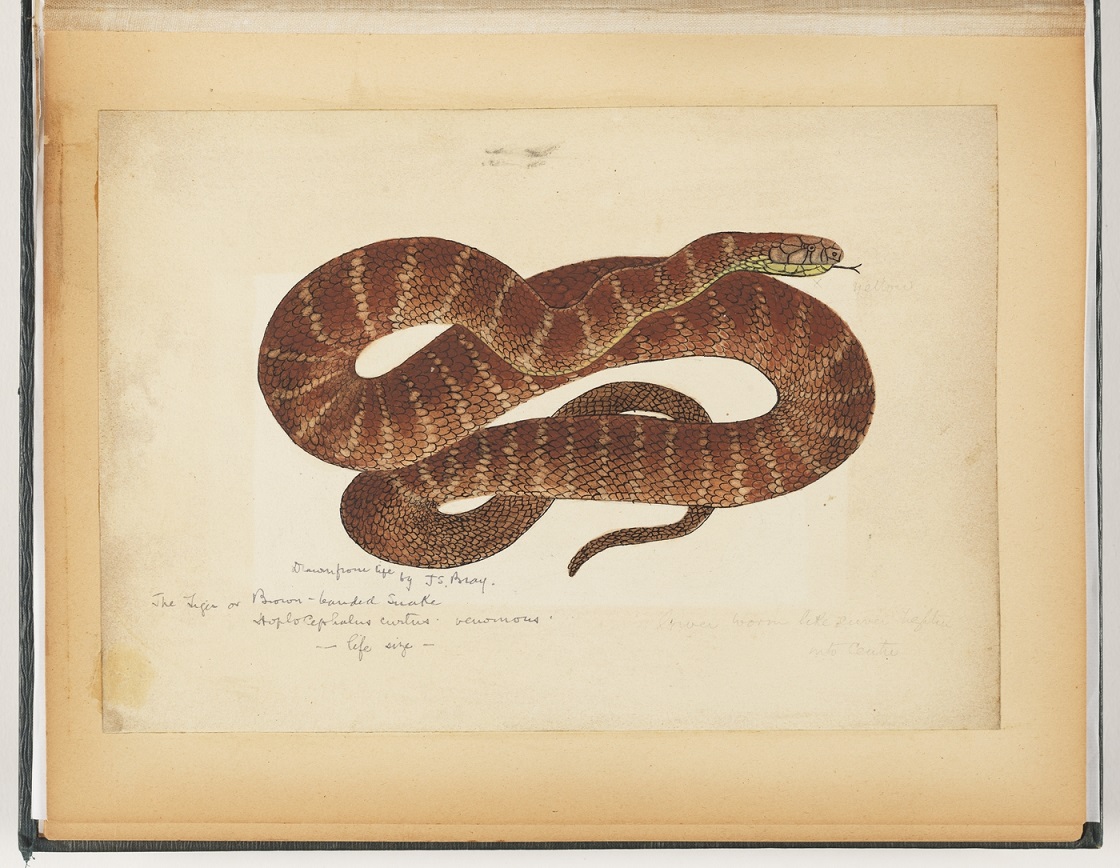

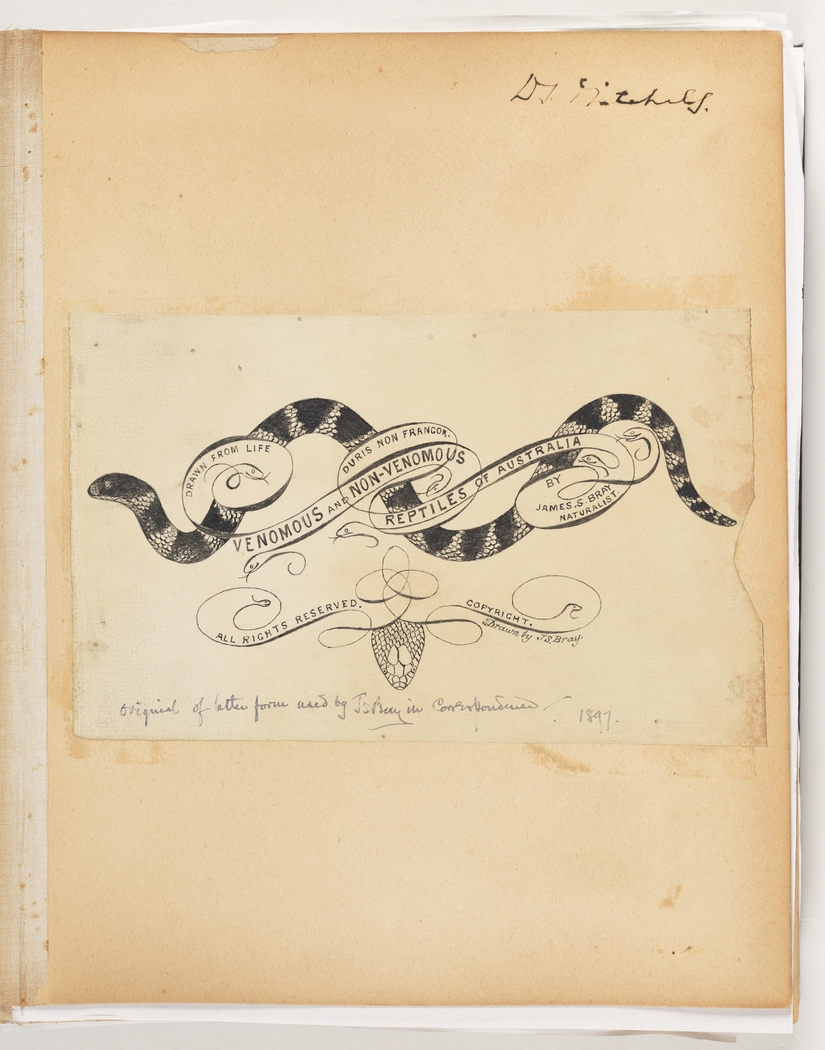

His promise of encounters with 'live venomous and non-venomous snakes' was certainly kept. Indeed, Bray displayed a decided affinity with serpents, regularly hunting, breeding and experimenting with them. His surviving notebooks and sketches abound with images of snake eggs, fangs and magnified crystals of dried venom. Like Krefft, Bray also documented the vivisections he performed – apparently in his museum – whereby snakes were induced to bite cats, rats and lizards, while he detailed their rapid expiry.[21]

[media]Bray was never short of subject matter, nor of words. In addition to another unpublished book, The Venomous and Non-Venomous Reptiles of Australia, he planned works on kangaroos, termites and a geological proof that 'Australia has risen out of the sea'.[22] His newspaper contributions proliferated, totalling hundreds of letters and articles in the Sydney press [23]. Bray furthermore corresponded with a multitude of citizens across the colony, receiving specimens and returning advice, while penning regular complaints that especially targeted the Sydney City Council.[24] It was thus no exaggeration to claim that Bray was a 'well-known naturalist' in Sydney, who continued publishing nature notes into World War I.[25]

The deep 1890s depression, however, sunk Bray's fortunes for good. In September 1892 he again declared himself bankrupt, forcing the closure of the Queen's Place museum. For the remainder of the decade Bray traded out of his new home at 100 Forbes Street, Woolloomooloo, where he continued breeding snakes. By now, however, his observational studies were being surpassed by Australian Museum zoologist Edgar Waite who in 1898 published A Popular Account of Australian Snakes.[26] Concurrently, at the University of Sydney, doctors Charles Martin and Frank Tidswell earned international acclaim for their laboratory studies of Australian venoms.[27]

Fading heyday

By the mid-1890s Bray's heyday had passed. Early in the new century he ceased trading and moved to Manly, unsuccessfully standing for election as an alderman before returning to Woolloomooloo around 1907. By this time, Mitchell had purchased Bray's papers, possibly because they included manuscripts from important colonial naturalists such as Krefft and Tasmanian botanist John Gunn.[28] Dying in a Marrickville private hospital in 1918, aged 69, Bray's funeral at Rookwood Necropolis was attended only by close family. No grave marker survives.

Although he never earned the scientific acclaim he craved, and soon lay forgotten, James Samuel Bray nevertheless embodied a sense of aspiration common to many late-Victorian colonists. If he failed to capitalise on their curiosity, his Museum of Curios captured something of the growing concern that sprawling modernity entailed irredeemable losses of Australia's natural and cultural heritage.

References

Bishop, Catherine. Minding Her Own Business: Colonial Businesswomen in Sydney. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2015.

Bray, James Samuel. Illustrations of Ethnology: with Description of Specimens from New Guinea (British & German Portions), Admiralty Islands, New Ireland, Duke of York Island, New Britain, Solomon Islands, New Hebrides, Samoan Islands, New Caledonia, Fiji, Northern Australia &c.,. Sydney: s.n., 1887.

Griffiths, Tom. Hunters and Collectors: the Antiquarian Imagination in Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Hobbins, Peter. Venomous Encounters: Snakes, Vivisection and Scientific Medicine in Colonial Australia. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017.

Souter, Gavin. Times & Tides: a Middle Harbour Memoir. Pymble: Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Notes

[1] Tom Griffiths, Hunters and Collectors: the Antiquarian Imagination in Australia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996, 121–75

[2] Geoff Huntington, 'Camden Villa – Built on the Rock, the Rock That Ever Stands', North Shore Historical Society Bulletin, June 2015, 4

[3] For example, James S Bray, 'The Natural History of North Shore: Snakes', n.d. [c1876], State Library of New South Wales, ML A 199

[4] Gavin Souter, Times & Tides: a Middle Harbour Memoir, Pymble: Simon & Schuster, 2004, 82–7

[5] 'List of Donations to the Australian Museum, During November, 1860', Sydney Morning Herald, 13 December 1860, 3

[6] A Krefft to James Samuel Bray, n.d. [c19 February 1881], Letters to James Samuel Bray, 1876-1984. (Inserted in Bray, J.S. - Natural history of North Shore, 1874), James Samuel Bray papers and sketches, ca. 1830-1896, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, ML A 199

[7] Bay View House – registers of patients and admission books 1865–1945, State Archives and Records New South Wales, Series 5162 item 5/5883, admission 128

[8] 'Deserting Wives and Families, Service, &C.', New South Wales Police Gazette, 29 March 1876, 95

[9] New South Wales. Blue Book for the Year 1875. Compiled from Official Returns in the Registrar General's Office, Sydney: Thomas Richards, 1876, 104

[10] The prospectus survives as James S Bray, A Narrative of the Discovery and Description of Contents of a Very Old Aboriginal Burying-ground, at Middle Harbour, 1888, State Library of New South Wales, DSM/572.991/B

[11] James Samuel Bray, Illustrations of Ethnology: with Description of Specimens from New Guinea (British & German Portions), Admiralty Islands, New Ireland, Duke of York Island, New Britain, Solomon Islands, New Hebrides, Samoan Islands, New Caledonia, Fiji, Northern Australia &c., Sydney: s.n., 1887

[12] New South Wales at the Melbourne International Exhibition, Sydney: Thomas Richards, 1880, 7

[13] Official Record of the New South Wales Commission for the Calcutta International Exhibition, 1883–1884, Sydney: Thomas Richards, 1885, 147

[14] New South Wales, Its Progress and Resources; and Official Catalogue of Exhibits from the Colony Forwarded to the International Exhibition of 1883–84 at Calcutta, Sydney: Thomas Richards, 1883, 162

[15] See for example R Etheridge to JS Bray, 6 August 1895, Australian Museum archives, AMS 19, volume 18

[16] A Handbook to St. John's College within the University of Sydney, Sydney: F. Cunninghame and Co, 1881, 41. I am grateful to Anne Coote and Perry McIntyre for supplying a copy of this rare booklet.

[17] For the enduring success of Tost & Rohu, see Catherine Bishop, Minding Her Own Business: Colonial Businesswomen in Sydney, Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2015, 231–4

[18] For example, WF Webb to Mr Bray, 19 October 1892, State Library of New South Wales, ML A 199

[19] Bray, James Samuel, Insolvency files, 1886, State Archives and Records New South Wales, Series 13654 item 20,487

[20] Bray's Museum of Curios letterhead, c 1888, in State Library of New South Wales, ML A 198

[21] See for example, State Library of New South Wales, ML A 195 and PXA 189

[22] Respectively, State Library of New South Wales, PXA 192, ML A 184, ML A 196 and ML A 198

[23] Trove, items tagged: James Samuel Bray http://trove.nla.gov.au/result?l-publictag=James%20Samuel%20Bray, viewed 2 August 2017

[24] For instance, Letters received, 1891, City of Sydney Archives, Item 26/248/408

[25] 'The Late Mr. J.S. Bray', Sydney Morning Herald, 4 April 1918, 7

[26] Edgar R Waite, A Popular Account of Australian Snakes with a Complete List of the Species and an Introduction to Their Habits and Organisation, Sydney: Thomas Shine, 1898

[27] Peter Hobbins, Venomous Encounters: Snakes, Vivisection and Scientific Medicine in Colonial Australia, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017, 137–163

[28] Margot Riley, 'An Exact Observer', SL, Autumn 2016, 29–31