The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Death and dying in twentieth century Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Death and dying in twentieth century Sydney

Mortality statistics

Mortality rates declined throughout the twentieth century. The dramatic drop in infant and child deaths in the first half of the twentieth century was a significant contributing factor to this remarkable shift in mortality statistics. [1] In 1901, the infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births in New South Wales was 103.7, in other words, nearly ten per cent of infants died. Infant mortality rates dropped to 69.5 by 1911 and two decades later was 43.5. By 1950 it was 27.0. The infant mortality rate did not fall below 10 deaths per 1,000 live births in New South Wales until 1983. [2]

Improved sanitation and hygiene contributed to a decline in all deaths from infectious diseases in the first half of the twentieth century, despite flawed medical understandings of the epidemiology and treatments of bacterial infections. It wasn't until the second half of the twentieth century that immunisation, antibiotics and improved medical care impacted upon mortality rates of infectious diseases, ensuring their continued decline. [3]

The Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest regional statistics for greater Sydney in 2011. In 2008, there were 26,759 deaths registered in Sydney, with a median age of death of 81.5 years. Of these deaths, there were just 246 infant deaths. This represents an infant mortality rate of just 3.9 per 1,000 live births in Sydney, lower than the state infant mortality rate of 4.5. [4]

Cremation

The push to introduce cremation in Sydney was an indication that attitudes towards death and the commemorative landscape were changing. The subject first received attention in November 1863 when Dr John Le Gay Brereton gave a lecture on urn-burial at the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts. Brereton was a medical man with an interest in homeopathic remedies and a social conscience. He also established Sydney's first Turkish Bath in Spring Street. He was a polished lecturer and regaled a 'fashionable audience, numbering about four hundred' with graphic descriptions of the failings of Sydney's cemeteries. Cremation was, arguing, 'a method more conducive to the health of the living'. [5] But it was another ten years before cremation really became topical among medical practitioners and the general public. The catalyst was an article by the prominent British surgeon Sir Henry Thompson, 'The Treatment of the Body After Death'. This article, which appeared in the Contemporary Review in Britain in January 1874, popularised the issue and led to vigorous debate in Britain, Europe and the Australian colonies:

…scarcely a journal in the country but had its chapter on the subject of 'Cremation' when that fashionable idea of disposing of defunct humanity was broached. [6]

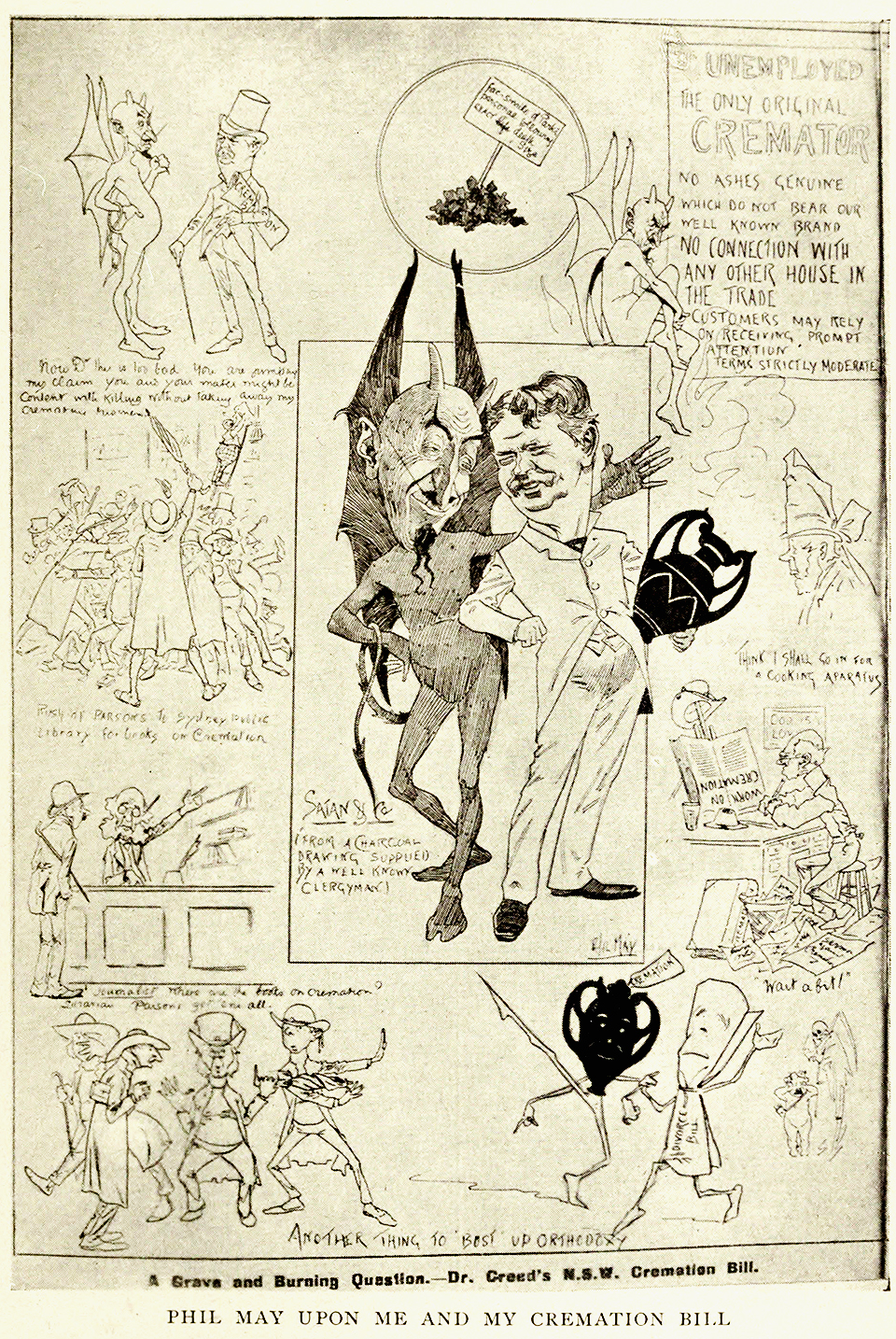

[media]The first attempt to introduce legislation to regulate cremation in NSW was by Dr John Mildred Creed in 1886. Advocates of cremation saw it as a viable alternative for disposing of the dead that would address the planning problems of cemeteries, would be an economic form of disposal that was cheaper than current practices and would be better for the health of the living. The bill faltered but the movement continued. The New South Wales Cremation Society was formed in 1890, following a meeting in the Royal Society's rooms, led by the indomitable Dr Creed. The movement attracted an impressive line-up of supporters, including parliamentarians, medical practitioners, journalists, social reformers and businessmen. The feminist, Rose Scott, was another avid supporter of the movement. [7]

Sydney inched its way slowly towards the introduction of crematoriums. The Public Health Act 1896 included a clause permitting local government authorities and cemetery managers to build and run crematoria within cemetery reserves. In 1900, an open air cremation of the remains of Frederick Farrant Cox, a theosophist, took place at Botany on government land. [8] In 1908, Dr Creed reinvigorated lobbying efforts by forming the Cremation Society of New South Wales, to replace its similarly named predecessor, which had limped along for a number of years. The Cremation Society of New South Wales waged a high-powered lobbying campaign, enlisting the support of the Board of Health, sending regular delegations to parliamentarians, circulating petitions and influencing newspaper editorials. [9] Despite efforts to get the state government to commit to financing a crematorium, the money was never forthcoming. Finally, in 1923, four acres (1.6 hectares) of land within Rookwood Necropolis was leased to the NSW Cremation Company (the commercial arm of the Society) for the purpose. The company, which had been gradually raising shareholders since 1915 and was formally registered in 1922, promptly issued its first prospectus to raise the necessary funds and build the crematorium. By September 1924 the company was ready to commence building. The first cremation took place at Rookwood Crematorium on 28 May 1925. In the first year, 122 bodies were cremated. [10]

Crematorium gardens

The introduction of cremation in the interwar period brought a new method of disposal and a new opportunity to design a commemorative landscape. While at first it may appear that cremation marked a dramatic change in the commemorative landscape, there were in fact many symbolic continuities between the cemetery and the crematorium garden. From its inception, the restful arboreal setting of Rookwood Crematorium was styled as a garden of memory and tender associations. The design intent of the crematorium landscape was exactly the same of the nineteenth century cemetery: to be a meditative aid to memory. By marketing crematoria landscapes in this way, the Cremation Society was tapping into commemorative traditions to help legitimise the new practice of cremation.

While employing many traditional funerary symbols, such as roses, poplars, cypress and urns, the landscape design and crematoria buildings were the latest in architectural style. With their stone flagging, Spanish mission decorative details and mix of formal and informal layouts, the crematorium gardens were typical of many interwar domestic and public gardens. The crematoria building themselves were a major feature in the landscape. In Sydney, Rookwood Crematorium (1925) and Northern Suburbs Crematorium (1933) were designed in the Italian Renaissance (interwar Mediterranean) style, while Woronora (1934) and Eastern Suburbs (1938) were Art Deco (interwar functionalist) designs. The adoption of these modern architectural styles projected a progressive image that was well aligned with the modern and hygienic stance towards the disposal of human remains. [11]

Since then, the popularity of cremation has gradually increased so that, by 1990, it was the most common method of disposal. In the twenty-first century, cremations account for approximately 60 per cent of disposals. The rise of cremation has coincided with the increasing privatisation of commemorative practices. In 1962, approximately 87 per cent of ashes were deposited in the grounds of crematoria or placed in a grave, while only 11 per cent were taken away by families. In 2000, only 34 per cent are lodged at crematoria or cemeteries, with 65 per cent of families taking the ashes away to keep or scatter themselves. The majority of these would have no public memorial at all. [12]

War

Historians have identified World War I as a turning point in the history of death and dying in Australia. The simplest argument is that the surfeit of death during World War I led to an erosion of the traditional culture of Christian death and led to a dramatic change in mourning culture. Cultural historians have refined this by looking at how the complex interplay between demographics, the medicalisation of society (which contributed to declining mortality rates), secularisation and changing religious beliefs, and the impact of war and death helps explain the shift in mourning practices that became noticeable after World War I. [13]

In many instances, World War I accelerated changes that were already taking place such as the movement towards simpler commemorative monuments. The wrench for many families was the denial of traditional mourning rituals. War deaths were often anonymous and ugly. In World War I, 42 per cent of Australia's dead remained missing, presumed dead. The grave traditionally provided a focus for memory. Pat Jalland records how many families were concerned to discover where their sons were buried and recalls how correspondence from soldiers back to grieving families frequently stated that their loved ones were given a 'decent' burial. In the absence of a grave, some grieving parents found consolation in letters and photographs as a source of memory. [14] Others turned to the local cemetery, adding a new inscription on the family memorial to their soldier hero, or even erecting a new monument, even though they were buried somewhere else, on the other side of the world. [15]

Medicalisation of death

The impact of the medical profession on the experience of dying and death in Sydney in the twentieth century was profound. Advances in medical science led to increased intervention in the dying process. Medicine, complex instruments and trained professionals drew the dying from the home into medical institutions. Greater life expectancy, another benefit of medical science, had the corollary of an elderly life requiring ever increasing levels of community and medical care. More than ever before, dying Sydneysiders were likely to be aware of their prognosis. [16]

Pat Jalland argues that the medicalisation of death has transformed our attitudes and responses 'from the more open and emotional to the silent and stoical'. [17] Funeral customs and death practices have responded accordingly. Undertakers transformed themselves into funeral directors, following trends in America. The development of funeral parlours and funeral chapels shifted funeral ceremonies away from the home and also the church.

Motorised hearses, widely introduced from the 1920s, changed the pace of the funeral and its location. The growing secularisation of society and medicalisation of death had the similar effect of distancing death. Increasing acceptance of cremation in the twentieth century was associated with these changing values; the chapel in the crematorium provided an alternative space for the funeral service.

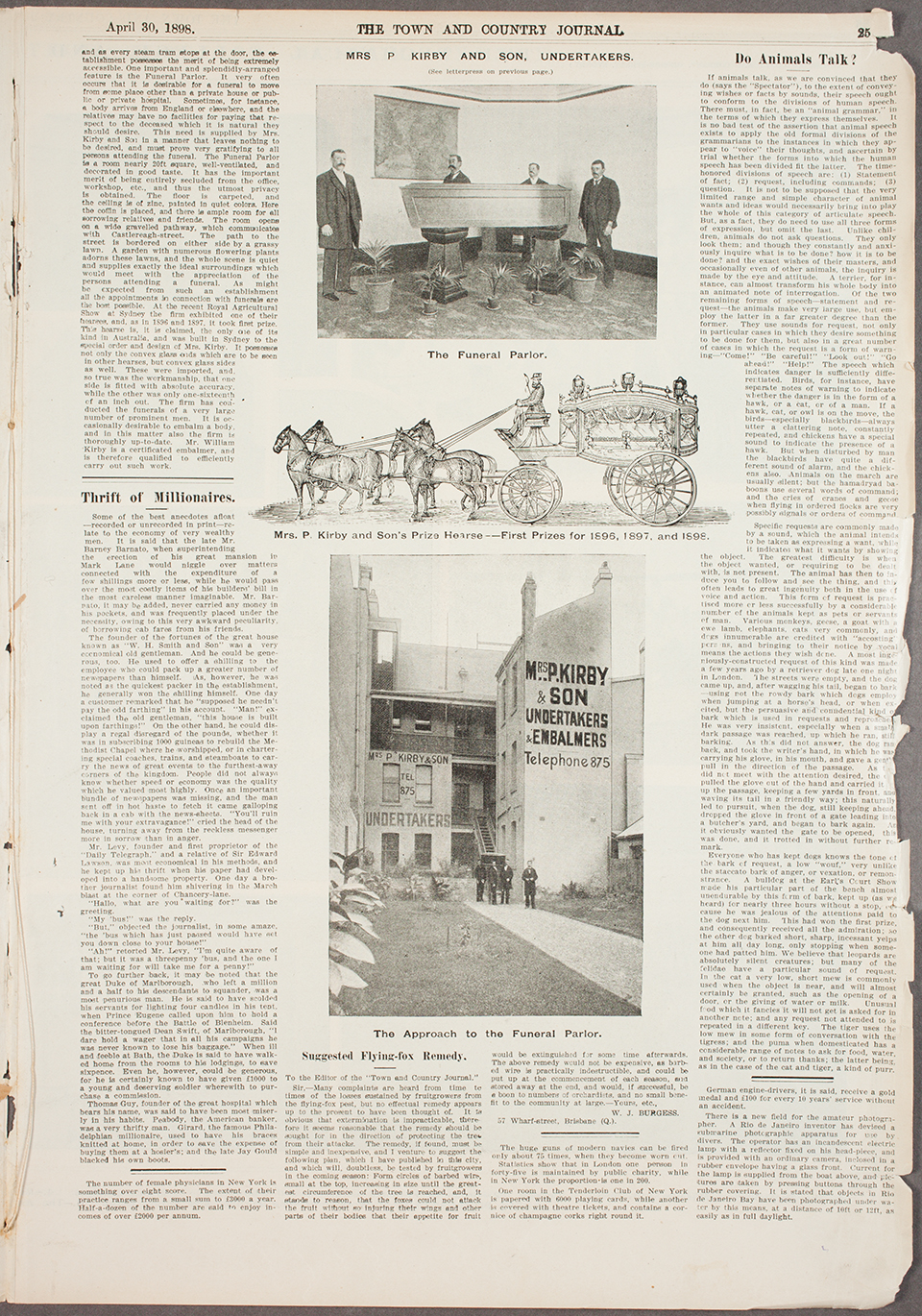

[media]Embalming and refrigeration allowed bodies to be kept for longer periods and allowed different commemorative practices to develop. Refrigeration became common from the 1920s. [18] Modern embalming practices are generally attributed to the influence of an American doctor after World War II. [19] Yet a form of embalming was introduced in Sydney as early as 1894 when another American, Professor G Hartford Rivers, established an Australian School of Embalming and, by 1900, undertakers and funeral directors were advertising their embalming techniques. [20]

Embalming made the practice of viewing the body in the funeral parlour more palatable. It also allowed above-ground tombs, crypts and mausoleums, favoured by many European migrants, to be constructed within cemeteries since the 1960s.

Migration and cultural differences

Religious observance is important to many ethnic minorities in Australia because it is a potent symbol of their cultural identity in a new society. Nowhere is this more dramatically realised than in cemeteries. As American historian Kenneth T Jackson points out, 'for immigrants, cemeteries fostered a sense of identity and stability in a new country characterized by change'. [21] Tensions between retaining cultural traditions and assimilation are demonstrated in the burial of successive generations of immigrants. The popularity of above-ground burial amongst southern European communities indicates a degree of assimilation. These communities initially wished to send deceased relatives back to their homeland for burial. The decision to bury their dead in Australia while retaining their traditional funerary practices suggests migrants gradually identified Australia as their homeland, a place for their family roots to develop.

The Chinese community put down similar roots in Australia. Traditionally, it was the desire of all Chinese to be buried in their ancestral home. If they died overseas, the body was buried for a short period of time – five to seven years – before the remains were exhumed and sent back to China for reburial. This was practised in Sydney throughout the nineteenth century. Through the twentieth century, the Chinese dead increasingly remained in Sydney. Rookwood Necropolis has been the site of Ching Ming (or 'Grave Sweeping Day') celebrations since the late nineteenth century.

[media]Cemetery trustees were fairly slow in adapting to the needs of ethnic communities. In the nineteenth century, the Jewish community was one of the few minority religious groups lucky enough to be granted their own burial space within government cemeteries. Most minority religious groups, such as the Chinese, had to be content with burying within the general or non-sectarian portion of the cemetery. It was not until the 1970s that areas were specifically designed for ethnic groups, meeting different monument and burial needs.

Cremation by the Roman Catholic Church was forbidden until 1963. Many Greeks and Italians still retain their opposition to cremation and insist upon burial. Mausolea, tombs and crypts all provide above-ground interment popular among southern European communities. Above-ground interment is now an accepted part of funerary culture in Sydney, to the extent that there is an Australian standard policy to ensure sound engineering and building practices.

Developments at Botany General Cemetery are fairly representative of the introduction of mausolea into Sydney cemeteries. The first mausoleum at Botany General Cemetery was built in 1952, two years after approval was given. Throughout the 1950s, the trustees of Botany Cemetery received one or two requests each year to build mausolea, all for non-Anglo-Saxon families. Since the 1960s, there has been increasing demand by the same communities for above-ground interment, such as crypts and tombs. [22]

In the Islamic faith, it is believed the body belongs to God. Cremation is therefore opposed due to a strong belief in the physical resurrection of the body. Burial takes place as soon as possible after death. The religious custom of direct earth burial has been a source of conflict with local authorities. In New South Wales, the Islamic Council of NSW and the Funeral and Allied Industries Union have agreed for bodies to be buried in a concrete-lined grave. The shrouded body is lowered into the grave within a specially designed coffin which can be dismantled and removed. Traditionally Islamic burials have no grave markers, however the practice is not universal and the majority of graves in Sydney are marked. [23]

Twentieth century cemeteries in particular reveal the expansion of multicultural Australia and the broadening of religious faiths. This was reflected in new burial areas, headstone design and symbolism, and inscriptions. In Rookwood Necropolis, over 80 different religions and denominational groups are represented. Many of these are accommodated within portions of the general and independent cemetery trust areas at Rookwood. In the twenty-first century, an ongoing challenge for cemetery managers and communities is to provide for the increasing demands for religious diversity and representation through separate burial areas in what are becoming increasingly crowded cemeteries.

Lawn cemeteries

By the 1950s and 1960s a generational shift in commemorative practices is apparent in the condition and visitation of cemeteries. Throughout the nineteenth century, grave owners could pay for annual or perpetual care of their grave plots. The prevailing culture of death at that time encouraged regular grave visitation and maintenance by relatives and friends. In the twentieth century, there were visible changes in the landscape. Cemeteries in metropolitan Sydney were filling up. Changing demographics meant that some areas of the cemetery became more visited than others and many graves were forgotten or neglected as relatives who once tended the graves moved away or died.

In response to these maintenance challenges, cemetery managers sought alternative designs for cemetery landscapes, such as the lawn cemetery. Lawn cemeteries were appealing to cemetery managers as they were more economical in their land use, as well as being easier to maintain. They brought with them specific regulations for memorial types and heights and usually excluded any form of enclosure or kerbing. Grave furniture was also kept to a minimum. A lawn cemetery did not need, nor did it encourage, regular grave visitation. The establishment of crematoria gardens – with their smaller commemorative plaques and neatly kept memorial gardens – may have helped smooth the way for the introduction of lawn cemeteries in Sydney after the World War II. The secularisation of society may also have made lawn cemeteries more acceptable because the grave was not a source of consolation for many; it was a reminder of loss rather than a source of consolation and faith. Nor was the cemetery as central to the memory and identity of the deceased. [24]

Woronora Cemetery in Sutherland was the first Sydney metropolitan cemetery to establish a section of lawn cemetery. It began considering the idea in 1950 and a nondenominational area was gazetted in late 1953. Northern Suburbs Cemetery (now Macquarie Park Cemetery) followed suit shortly afterwards. Pine Grove Memorial Park (a private cemetery run by a company) at Eastern Creek was established nearly ten years later in 1962. The 180 acres (73 hectares) was Sydney's first major lawn cemetery. It promised 'gently sloping lawns' and 'everlasting beauty, dignity and serenity' that would be 'maintained forever' [25]. Forest Lawn Memorial Park at Leppington was also established in the same year.

Palliative care and HIV / AIDS

Palliative care has a long history in Sydney through the Sisters of Charity. Whist the modern hospice movement in this country dates from the 1970s, the Sacred Heart Hospice, founded by the Sisters of Charity in Darlinghurst in 1890, was the first hospice in Australia. [26] Associated with St Vincent's Hospital, the Sisters of Charity have continued to lead the way in palliative care, particularly since the 1980s in the care of AIDS sufferers.

The first cases of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were reported in the 1980s. Patterns of infection differ around the world. In Sydney the most vulnerable groups have been men who have sex with men and intravenous drug users, both socially marginalised groups. Difficult to treat, the appearance of HIV led to dramatic public health campaigns aimed at changing social behaviours. Consequently, the disease became stigmatised and the experience of living with HIV and dying from AIDS could not be removed from this social context. [27]

Due to the relative young age of many AIDS victims, this new disease challenged modern concepts of life expectancy and the right to die. The devastating impact of the disease in the gay and lesbian community has left few untouched by the slow, anguished deaths. The artistic community in particular responded with their art as a form of public grief and mourning.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt is an important form of grieving for many gay and lesbians in Sydney and around Australia. Andrew Carter and Richard Johnson, inspired by the American NAMES project, established the quilt in September 1988.

Since the mid-1980s, the annual Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade has incorporated elements of commemoration and thanksgiving of AIDS support groups within the celebration. Ted Gott sees the annual parade's fusion of remembrance as central to the gay community's identity in the 21st century:

The Mardi Gras Parade has become, in one sense, the equivalent of Anzac Day for Australia's gays and lesbians, as they remember their dead, celebrate their communities' survival, and express their fierce will to rise stronger out of the fires of tragedy. [28]

Burial crisis in the 21st century

In the twenty-first century, Sydney is experiencing a burial crisis. The government has not planned new cemeteries since the mid-twentieth century and Sydney's cemeteries are once again reaching capacity. In 2008, a discussion paper on sustainable burial practices was released by the state government, floating the idea of the introduction of renewable tenure within the greater Sydney metropolitan area to deal with the imminent crisis. Although opposed by some groups on religious grounds, most notably the Muslim community, the adoption of such practices would be another catalyst for major changes in the cultural practices of death in Sydney.

References

Pat Jalland, Australian Ways of Death: A Social and Cultural History 1840–1918, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2002

Pat Jalland, Changing Ways of Death in Twentieth Century Australia: War, Medicine and the Funeral Business, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2006

Allan Kellehear (ed), Death and Dying in Australia, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2000

Allan Kellehear, A Social History of Dying, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007

Robert Nicol, This Grave and Burning Question: A Centenary History of Cremation in Australia, Adelaide Cemeteries Authority, Adelaide, 2003

Notes

[1] Jake M Najman, 'The Demography of Death: Patterns of Australian Mortality' in Allan Kellehear (ed), Death and Dying in Australia, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2000, p 32

[2] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 'Table 6.4: Infant Mortality Rates, States and Territories, 1901 onwards', 3105.0.65.001 – Australian Historical Population Statistics, 2008, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3105.0.65.001/, accessed 10 June 2013

[3] Jake M Najman, 'The Demography of Death: Patterns of Australian Mortality' in Allan Kellehear (ed), Death and Dying in Australia, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2000, p 32

[4] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 'Table 10: Deaths by Region, NSW – 2008', 1338.1 – NSW State and Regional Indicators, 2010, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1338.1, accessed 10 June 2013

[5] Simon Cooke, 'Death, Body and Soul: The Cremation Debate in New South Wales, 1863–1925', Australian Historical Studies, no 97, October 1991, pp 324–5; Robert Nicol, This Grave and Burning Question: A Centenary History of Cremation in Australia, Adelaide Cemeteries Authority, Adelaide, 2003, pp 11–17

[6] Illustrated Sydney News, 17 October 1874, p 2; Simon Cooke, 'Death, Body and Soul: The Cremation Debate in New South Wales, 1863–1925', Australian Historical Studies, no 97, October 1991, p 324; Robert Nicol, This Grave and Burning Question: A Centenary History of Cremation in Australia, Adelaide Cemeteries Authority, Adelaide, 2003, pp 171–175

[7] Robert Nicol, This Grave and Burning Question: A Centenary History of Cremation in Australia, Adelaide Cemeteries Authority, Adelaide, 2003, pp 50–57, 151–153; ADB

[8] Robert Nicol, This Grave and Burning Question: A Centenary History of Cremation in Australia, Adelaide Cemeteries Authority, Adelaide, 2003, 75

[9] Robert Nicol, This Grave and Burning Question: A Centenary History of Cremation in Australia, Adelaide Cemeteries Authority, Adelaide, 2003, ch11

[10] Robert Nicol, This Grave and Burning Question: A Centenary History of Cremation in Australia, Adelaide Cemeteries Authority, Adelaide, 2003, ch 14

[11] Lisa Murray, 'Monumental Changes: Headstone Designs and Commemorative Landscapes in New South Wales, 1870–19701', in Stephen Gregory (ed), Shop Til You Drop: Essays on Consuming and Dying in Australia, Southern Highlands Publishers, Sydney, 2008, p 95–96

[12] These statistics are primarily based on crematoria in NSW. Sharon Losik, 'History in Ashes – The Popularisation of Cremation in Australia 1925–2000', BA Hons thesis, University of Sydney, 2003, p 70

[13] See in particular Pat Jalland, Changing Ways of Death in Twentieth Century Australia: War, Medicine and the Funeral Business, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2006

[14] Pat Jalland, Australian Ways of Death: A Social and Cultural History 1840–1918, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2002, ch 16 and Changing Ways of Death in Twentieth Century Australia, part 2

[15] Lisa Murray, 'Monumental Changes: Headstone Designs and Commemorative Landscapes in New South Wales, 1870–19701', in Stephen Gregory (ed), Shop Til You Drop: Essays on Consuming and Dying in Australia, Southern Highlands Publishers, Sydney, 2008, p 92

[16] Jake M Najman, 'The Demography of Death: Patterns of Australian Mortality' in Allan Kellehear (ed), Death and Dying in Australia, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2000, p 33; Pat Jalland, Changing Ways of Death in Twentieth Century Australia: War, Medicine and the Funeral Business, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2006, pp 193–207

[17] Pat Jalland, Changing Ways of Death in Twentieth Century Australia: War, Medicine and the Funeral Business, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2006, p 194

[18] Pat Jalland, Changing Ways of Death in Twentieth Century Australia: War, Medicine and the Funeral Business, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2006 p 284

[19] Sue Zelinkda, Tender Sympathies: A Social History of Botany Cemetery and the Eastern Suburbs Crematorium, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, pp 82–3

[20] Pat Jalland, Changing Ways of Death in Twentieth Century Australia: War, Medicine and the Funeral Business, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2006, pp 283–284

[21] Kenneth T Jackson, Silent Cities: The Evolution of the American City, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1989, p 60

[22] Sue Zelinka, Tender Sympathies: A Social History of Botany Cemetery, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, p 87

[23] James Selby, 'Appendix 2: Report on Particular Thenic Background and Funerary Needs', Rookwood Necropolis Plan of Management, NSW Department of Public Works, 1993, pp 6–7

[24] Lisa Murray, 'Monumental Changes: Headstone Designs and Commemorative Landscapes in New South Wales, 1870–19701', in Stephen Gregory (ed), Shop Til You Drop: Essays on Consuming and Dying in Australia, Southern Highlands Publishers, Sydney, 2008

[25] ?

[26] Sanchia Aranda, 'Palliative Nursing in Australia' in Allan Kellehear (ed), Death & Dying in Australia, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2000, pp 255–258

[27] Brian Kelly, 'HIV/AIDS' in Allan Kellehear (ed), Death & Dying in Australia, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2000, , pp 145–162; Allan Kellehear, A Social History of Dying, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007, pp 213–215

[28] Ted Gott, 'Agony Down Under: Australian Artists Addressing AIDS' in Ted Gott (ed), Don't Leave Me This Way: Art in the Age of AIDS, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2004, p 27

.