The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Italians

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Italians

In 1840 the British Government abolished the transportation of convicts to New South Wales and opened the doors to free immigration. People born on the Italian peninsula began emigrating to Sydney even before the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy on 27 March 1861.

Early Italians

Other than adventurers, explorers and sailors who 'jumped ship', missionaries and political refugees were among the first to reach Sydney. In 1843, three Italian Passionist priests were brought to Sydney by John Bede Polding, the first Catholic bishop in Australia. Their immediate impression of the colony was most enthusiastic. Father Raimondo Vaccari remarked that

this fifth part of the world … without the slightest exaggeration … can be called a terrestrial paradise.

Among the other clergy who soon after arrived in Sydney was the Sicilian Benedictine Father Emanuele Ruggero, who worked in Campbelltown, Camden and St Marys. Father Pietro Magagnotto arrived in 1847 and in 1850 became the Dean of Sydney.

In the second half of the 1840s, some 70 Lombard stonemasons were contracted by a Frenchman, Jules Joubert, to come to Sydney, where they built the village of Hunters Hill, and many of them settled. Joubert recounted that

it was possible for me, with the help of those capable Italian stonemasons, to accept other contracts of work in Sydney and district and to erect big buildings and warehouses.

Some of them were politically active. Giovanni Cuneo built and managed the Garibaldi Hotel in Hunters Hill, complete with a statue of the Italian patriot at the entrance of the inn. It became a favourite meeting place for Italians. Another political refugee was Gian Carlo Asselin, a Neapolitan who had taken part in the liberal uprising of 1848 and in Garibaldi's unsuccessful attempt to wrest Rome from the Pope in 1849. He became Italian Vice-Consul in Sydney in 1861.

However, Victoria attracted most Italian migrants, following the discovery of gold in that state and the ensuing rapid growth of Melbourne. In a note to his consul in Melbourne, dated 22 April 1859, the Foreign Minister of the Kingdom of Sardinia bluntly stated that:

Sardinian interests lie not in Sydney, but in Melbourne … that, although recently founded, is already more important than Sydney … [also], the Ministry was not able to find in Sydney a person suitable to be appointed Consul.

Hard times

In 1856, the Sardinian vessel Goffredo Mameli arrived in Sydney with a cargo of marble, bricks, wine and 84 emigrants. Its captain was Nino Bixio, who would become Garibaldi's famous second-in-command. The Sardinian Ministry of Foreign Affairs emphasised the importance of this voyage, hoping that

in Australia our emigrants will enjoy a reputation of probity and disposition to work and that the future will bear evidence of this truth.

Unfortunately, the ministry's hopes were dashed by the harsh reality of destitution and alienation that affected many migrants. Francesco Sceusa, another political refugee, who arrived in Sydney in 1877, reported that Sydney, at that time, hosted an Italian community of fewer than 500 people. Many of them lived in abysmal conditions in what the Australian press disparagingly called Macaroni Row, a cluster of 36 putrid and miserable houses in Castlereagh Street. They earned their living by selling 'hokey-pokey' (ice cream), fruit and flowers, or as street musicians and organ grinders, begging in the streets with the inevitable monkey on their shoulders. 'There are approximately 100 Sicilians here in Sydney', reported Sceusa,

eighty of whom are fruit sellers. Of the same number of Neapolitans in the colony, more than half are street musicians. Of the 40 Tuscans, 20 are figurine-makers, producing, with some effort if you wish, but without taking their pipe from their mouth, a number of Madonnas and Venuses which are useless and which Australia does not need.

However, a few Italians were able to emerge from this desolate social landscape. [media]Tommaso Sani's statues adorned the General Post Office and Achille Simonetti decorated the Colonial Secretary's building and made the statue of Governor Arthur Phillip in the Botanical Gardens.

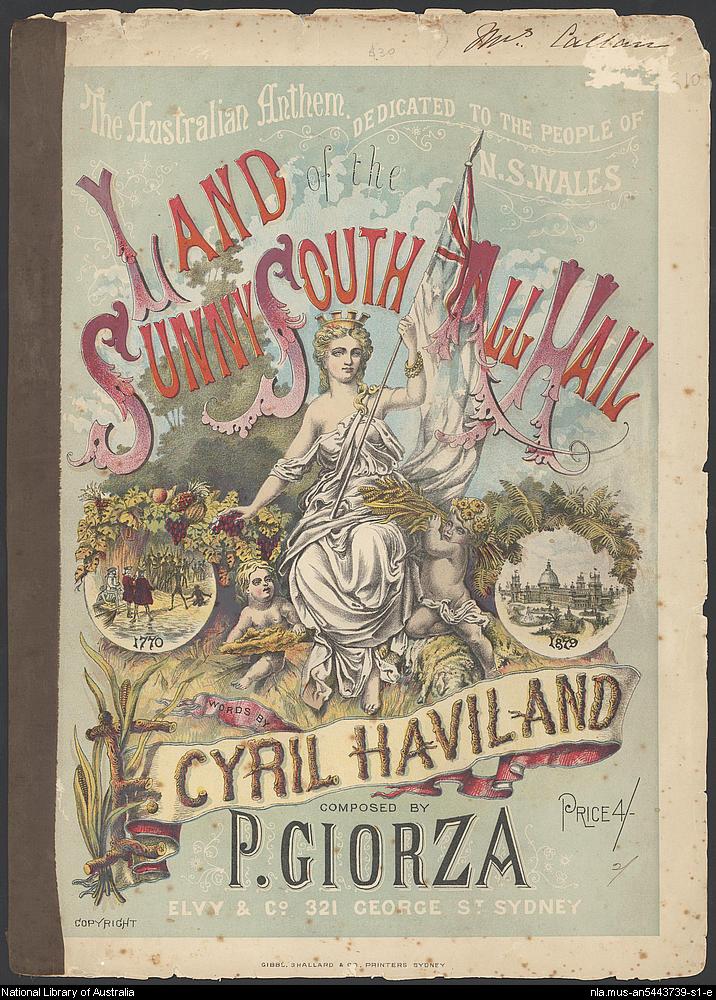

In 1879 the Great International Exhibition was held in Sydney, with the participation of 50 Italian firms. Typical products exhibited were marble statues, mosaics, straw hats, wines, liqueurs, preserved fruit and machinery for the manufacture of pasta and the production of oil. [media]The highlight of the closing ceremony of the exhibition was the performance of the hymn 'Australia', composed by Milanese maestro Paolo Giorza.

In April 1881, Sydney witnessed a remarkable gesture of human solidarity when the 217 Italian survivors of the ill-fated Marquis De Rays expedition to New Ireland arrived at Circular Quay. They were lodged in a shed in the Domain and the New South Wales government provided medical care, food and clothing, while an Italian merchant, Gianbattista Modini, brought ten boxes of spaghetti. [media]As the government did not want to create a colony within the colony, they were scattered to faraway places, where they proved to be 'industrious, hard working and honest people'. One year later, in April 1882, they got together and founded the colony of New Italy, near Woodburn in northern New South Wales.

Building a community

On 2 June 1882 Giuseppe Garibaldi died. On 17 June, Sceusa organised a commemoration of his death at the Garden Palace, attended by over 10,000 people. The Illustrated Sydney News reported

flags and other appropriate emblems were disposed about the building with great effect. In front of the platform there was a colossal bust of Garibaldi, admirably executed by Signor Sani in six days, and which occupies a prominent place in our engraving. The whole of the decorations were designed by Signor Francesco Sceusa of the Survey Department and carried out with artistic completeness.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Sceusa and a group of his socialist refugee friends were instrumental in raising the profile of Italians in Sydney. In 1882 he set up an Italian Benevolent Society and in January 1885 began publishing the first newspaper in the Italian language in Australia, the Italo-Australiano . Only six issues were printed, because in September 1885 Sceusa was transferred to Orange by his employer, the New South Wales Department of Lands. In 1891 Sceusa established an Italian Workingman's Benefit Society, of which he was President. Both societies were wound up in 1902. In 1903, Giuseppe Prampolini, who had fled Italy following the Milan bread riots of 1898, launched his weekly newspaper Uniamoci (Let's unite).

The 1901 census registered the presence of 5,678 Italians in Australia. Of them, 915 lived in Sydney. The Circolo Isole Eolie (Eolian Islands Club) was founded in 1903 at Circular Quay and the Società Stella d'Italia (Italian Star Society) in 1906. A new Italo-Australiano appeared in 1905 (its last issue appearing on 30 January 1909), and Oceania in 1913. A Club Italia was established in 1915 at 174 King Street.

The size of the Italian community in Sydney had remained the same: the 1911 census accounted for 940 Italians. Here, they found employment on a fairly narrow range of occupations: restaurants, fruit and vegetable growing and vending, fishing, and importing foodstuffs from Italy. From the turn of the century, Italians had used the boarding houses in Stanley Street, East Sydney, as their preferred abode. Soon, Italian food outlets began appearing in this street. In 1914, the Sydney Macaroni Manufactory was established in Stanley Street, a business that lasted for 20 years.

Growth and success

Following World War I and the restrictions on European migration imposed in 1921 by the United States of America, Italian migration to Australia increased considerably. The 1921 census registered 8,135 Italians, of whom 1,271 were residing in Sydney, while the 1933 census accounted for 26,756, of whom 3,325 were Sydneysiders. [media]Woolloomooloo, Balmain, Glebe, Annandale, Leichhardt, Kings Cross and Darlinghurst were the main inner city centres for Italians. Suburban Italian settlements were in Cabramatta, Canley Vale, Liverpool, Sutherland, Fairfield and Eastwood. There were 800 Italians living in these suburban areas by 1940. This period of demographic growth led to flourishing commercial, cultural and political activities.

[media]The Italian business elite in Sydney consisted of a small group of old-time migrants who had been financially successful, like the food importer Bartolomeo Callose; Pietro Melocco, owner of Melocco Bros, supplying terrazzo and marble works; Matteo Fiorelli, wine merchant; Antonio Despas of Cinzano (Australia), wine merchants; Luigi Gariglio, involved in import-export with Italy; and Francesco Lubrano, shipping agent and owner of the Italo-Australian (9 August 1922–8 June 1940).

Politics and celebrations

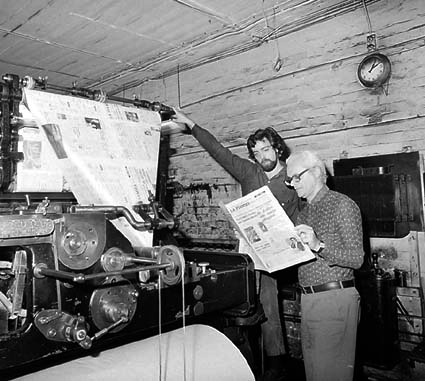

[media]From 1922, the Dante Alighieri Society became active in the cultural field by publishing its Italian Bulletin of Australia, supportive of the Italian fascist government. Conversely, anti-fascist activities were carried out by a group of militants who rallied around the newspaper Il Risveglio (The Awakening) printed in Annandale. It enjoyed only a short life, as it was banned by the Commonwealth government after representations by the Italian Consul-General. During the 1930s, the main voices of the Italian community in Sydney were Lubrano's Italo-Australian and the Giornale Italiano, which began publishing in 1932. Both sheets, strongly supportive of the Italian fascist government, were closed by the Commonwealth government in June 1940.

One of the most lavish Italian social events in Sydney took place in 1928, when Italian soprano Toti Dal Monte married her leading tenor, Enzo de Muro Lomanto in St Mary's Cathedral. A crowd estimated at 25,000 surrounded the building. Sydney had never enjoyed a more spectacular wedding, claimed the Sydney Morning Herald . Other key Italian celebrations were the arrival in Sydney from Rome, in 1925, of a twin-engined seaplane piloted by Wing Commander Francesco de Pinedo, and the visits of Italian warships Libia in 1922, Armando Diaz in 1934 and Raimondo Montecuccoli in 1938.

Enemy aliens interned

The outbreak of the war, and Italy's declaration of war on Britain and France in June 1940, meant that Sydney's Italians were considered enemy aliens and therefore subject to internment. By March 1944, out of an Italian population in New South Wales of 12,348, 1,536 were interned. Of the 1,647 Italians residing in Sydney's metropolitan area (316 of whom lived within the city area), many were interned, although no final figure is available. The main New South Wales internment camps were situated at Liverpool, Hay, Cowra and Orange. To many Italian internees, Australia meant almost five of the best years of their life spent in captivity, far away from their homes, families and friends. The psychological, mental and physical stress of long years of confinement and isolation left enduring marks on their characters.

Postwar migration

The postwar period saw the greatest [media]influx of Italians in Australia's history. The 1947 census registered 33,632 first-generation Italians residing in Australia, while that of 1971 accounted for a peak number of 289,476. Sydney's Italian population increased accordingly, to the point that by 1961 over 6,000 Italians [media]resided in the City of Sydney local government area.

Italians in Sydney 1881–2006

| Year | Italians in metropolitan Sydney | Year | Italians in metropolitan Sydney |

| 1881 | 211 | 1961 | 43,788 |

| 1901 | 915 | 1966 | 56,304 |

| 1911 | 940 | 1971 | 64,380 |

| 1921 | 1,271 | 1976 | 66,657 |

| 1933 | 3,325 | 1981 | 62,682 |

| 1947 | 4,279 | 1986 | 59,581 |

| 1954 | 18,976 | 2006 | 44,517 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics figures and Graeme Hugo, Atlas of the Australian People. New South Wales, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1992, p 83

[media]The exponential growth of the Italian community in Sydney stimulated social, economic, political and community life. In 1944 the anti-fascist sheet Il Nuovo Risveglio began publication and in 1947 the Catholic newspaper La Fiamm a was launched to counteract left-wing influence, followed by the appearance in 1962 of Settegiorni, a right-wing weekly. By 1958, the twice-weekly La Fiamma had a print run of 28,000, and by 1967 the newspaper had a readership of 44,000.

Italian clubs and restaurants mushroomed all over the city. The Italo-Australian Club in George Street was a place where, in the 1950s and 1960s, migrants could have a meal, buy Italian newspapers and attend social events and dancing nights. [media]In Stanley Street, the restaurants La Veneziana opened in 1952 and No Name in 1959. Nearby, in Yurong Street, Giuseppe Polese opened his famous Beppi's Restaurant in 1956. In 1992, he would also establish the restaurant Mezzaluna in Potts Point.

Leichhardt became a Little Italy, an established business area for Italian real estate and travel agents, taxation agents, driving schools, law firms, pastry shops, bridal and gift shops, butchers and delicatessens, furniture and clothing shops, as well as restaurants and cafes. Between 1858 and 1933, 259 Italian-run shops and businesses had been established in this area, although this number never operated at the same time. In 1976, there were 176 Italian businesses in Leichhardt.

In 1954 the Associazione Polisportiva Italo-Australiana, the APIA Club, opened in Norton Street, Leichhardt, and moved to Fraser Street in 1962. By 1970, the club had more than 13,000 members, 49 per cent of whom were not Italian. In Bossley Park, the Marconi Club was established in 1956. Other iconic meeting places for Italians were the Atlanta Club, Mario Abbiezzi's Garibaldi Bar in Riley Street, the Bar Coluzzi in Darlinghurst, and the Café Sport in Leichhardt.

Welfare and employment

In the postwar period, Italian welfare organisations were set up to cater for the newly arrived. During the 1950s, Lena Gustin, who became affectionately known as Mamma Lena, began broadcasting a radio program called Arrivederci Roma , lobbying politicians and bureaucrats for assistance to needy Italians. Also from the early 1950s, the Italo-Australian Welfare Association operated from the Casa d'Italia in Surry Hills helping the Italian community. In 1968, the association merged with the newly formed Italian Welfare Committee (CoAsIt). This organisation has been integral to the provision of services related to education, health, child care and the care of the ageing. Another organisation important for the cultural development of the community was FILEF, which in 1975 opened its centre in Parramatta Road, Leichhardt.

Most postwar migrants found employment in the construction industry. 1966 census data noted that Italians predominated in plaster, concrete, bricklaying and terrazzo work. The main suppliers of labour were Sydney's Italian companies. Pioneer Concrete, Australia's biggest concrete company, was formed in 1950 by Vicenza-born Tristan Antico (who arrived in Australia in 1930, aged seven). Other Italian-founded companies included Electric Power Transmission, established in 1951, Transfield, set up in 1956, Multicon, founded in 1973, Sabemo, created in 1958, and Melocco Brothers, the terrazzo business that began operating in Sydney in 1908.

However, in the 1960s some Italians still laboured on the land, even in metropolitan Sydney, where they owned orchards, poultry farms and market gardens in Brookvale, Ryde and Marsfield. The site where Macquarie University now stands accommodated 109 farms, 59 of which belonged to Italians.

Among the many Italians who distinguished themselves during this period, must be mentioned Claudio Alcorso, chairman of the Australian Opera, Evasio Costanzo, editor of La Fiamma, Paolo Totaro, chairman of the Ethnic Affairs Commission, Franca Arena, Member of the Legislative Council of New South Wales, painter Salvatore Zofrea, industrialists Franco Belgiorno-Nettis and Carlo Salteri, biotechnologist Alessandra Pucci, architect Dino Burattini and fashion designer Carla Zampatti.

Demographic decline, cultural renewal

From 1971, the Italian community in Sydney suffered a steady decline in numbers and a progressive cultural loss by reason of the end of Italian immigration. For instance, Leichhardt had 5,000 Italians in 1971, 3,922 in 1976 and 1,872 in 1991. The 2006 Census registered 44,517 Italian-born people living in metropolitan Sydney, while 71,639 declared that they spoke Italian at home. Out of a Sydney population of 4.1 million, 173,332 people stated that they had Italian ancestry, with second-generation Italians (one or both parents born overseas) numbering 131,477, and third-generation Italians (both parents born in Australia) 41,855.

Despite its demographic decline, the importance to Italy of its community in Australia is evidenced by the official visits paid by three presidents of the Italian Republic: Giuseppe Saragat in 1967, Francesco Cossiga in 1988 and Oscar Luigi Scalfaro in 1998. Italian influence on Sydney's life remains strong. Italian feste, like the Blessing of the Fleet, held at Darling Harbour by Sicilian and Calabrian fishermen, and the religious Brookvale processione, are still attracting a wide Australian audience. The Italian Film Festival, at Norton Street, Leichhardt, remains a key cultural event. Activities promoted by the Italian Cultural Institute, by CoAsIt and by the Dante Alighieri Society influence Sydney's cultural scene. [media]Together with the contribution made by Italian immigrants to the city's development, the innovative additions to Sydney's cityscape made by Italian architects, such as Renzo Piano's Aurora Place in Macquarie Street and the Italian Forum in Leichhardt, designed by Romaldo Giurgola, also designer of Parliament House in Canberra, are a clear sign that Italy is alive and well in Sydney.

References

Gianfranco Cresciani, Fascism, Anti-Fascism and Italians in Australia 1922–1945, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1980

Gianfranco Cresciani, The Italians in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2003

Gianfranco Cresciani, 'Lo Spettro Della Quinta Colonna Italiana In Australia: 1939–1942', Affari Sociali Internazionali, Year XIII, no 4, 1985, pp 45–61

Gianfranco Cresciani, 'Peasant Immigration in Australia. 1920–1940', Spunti E Ricerche, vol 2, 1986

Gianfranco Cresciani, 'The Making of a New Society: Francesco Sceusa and the Italian Intellectual Reformers', in John Hardy (ed), Stories of Australian Migration, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, New South Wales, 1988

Gianfranco Cresciani, 'The Bogey of the Italian Fifth Column', in Gaetano Rando and Michael Arrighi (eds), Italians in Australia: Historical and Social Perspectives, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales,1993, pp 67–83

Gianfranco Cresciani, 'Refractory Migrants. Fascist Surveillance on Italians in Australia. 1922–1943', Italian Historical Society Journal, vol 15, 2007, pp 9–58

Gianfranco Cresciani, 'A Not So Brutal Friendship. Italian Responses to National Socialism in Australia', Altreitalie, 34, January–June 2007, pp 4–38