The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Defending colonial Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Defending colonial Sydney

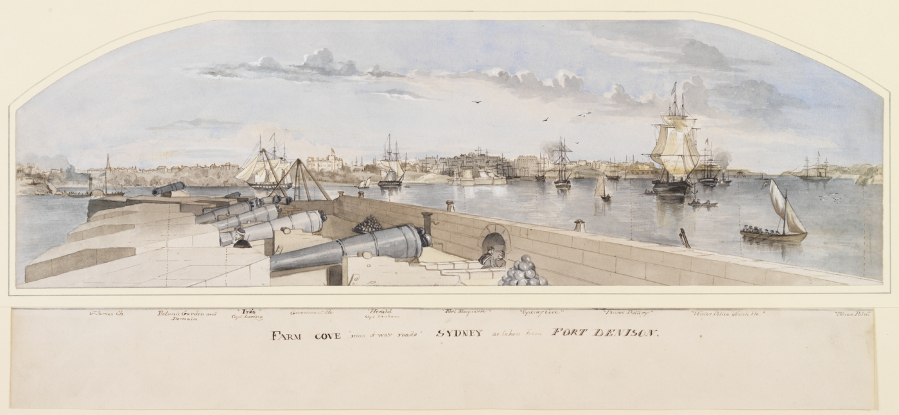

[media]Passengers on Sydney's harbour ferries might wonder, as they pass Fort Denison and old gun emplacements on the various headlands, why Sydneysiders felt so in need of fortifications in the nineteenth century. Numerous military relics are reminders that Sydney Harbour once bristled with cannon and big gun batteries, ready to deter anticipated attacks by privateers or enemy warships. For more than a century, Sydney faced recurrent and often well-founded fears of raids and even invasion. These fears were ignited as the British Empire's enemies and rivals over the century – America, France, Spain, Russia, and Germany – sent warships into the Pacific to annexe territories for themselves. Sydney was a potentially desirable conquest. Its strategically important harbour was the envy of all navies, its defending population was small, and – at mid-century – its bank vaults groaned with bullion from the gold fields. Fortress Sydney grew out of anticipated dangers that could not be ignored. Time and again, invasion scares set off anxious debate in the public, press and government. Royal commissions and defence inquiries repeatedly found Sydney vulnerable, and resulted in a flurry of fortification construction.

[media]By the early 1890s, focus had moved from the inner harbour to defending the entrance, and to Botany Bay, and particularly the city's eastern coastline, where new cliff-top forts at Vaucluse, Bondi and Clovelly housed large anti-bombardment guns to deter expected assault by powerful new iron-clad, steam-powered warships. By then, the balance of power to Australia's north had changed and the Japanese, too, were seen as a threat. These fears were not an all-consuming preoccupation – Sydneysiders got on with their everyday lives and joys – but they were always present as the city flourished. Certainly the scares at times reached fever pitch when Sydney's vulnerability was revealed. [1] In hindsight, it is easy to dismiss these recurrent scares as over-reactions to foreign events, as fantasies inflamed by alarmist speculation in the local press. There is some element of that. But a careful examination of Sydney's many periods of tension shows that the city's fears were often well-founded. The dangers were real.

The anticipated attacks never came, of course, but the potential threats were no less believable or anxiety-provoking to Sydney people at the time. From its antipodean isolation, Sydney watched Britain constantly engaged in imperial conflicts, and her enemies and rivals seeking expansion into Asia and the Pacific. As the century wore on, however, Britain's unprecedented military power appeared less invincible. By the end of 1870, Britain had withdrawn her last garrison from Sydney, and in the following decade even the supremacy of the Royal Navy, so long indisputable mistress of the seas and seen by Sydney as a protector, was under challenge.

Earliest European defences

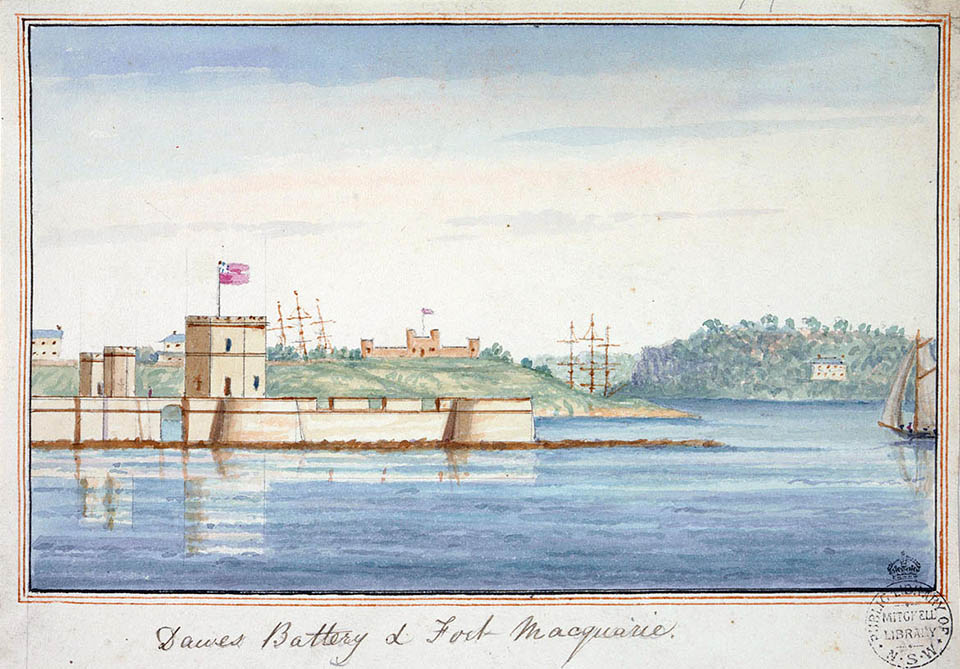

[media]The first of the defences of the convict settlement was built within weeks at Sydney Cove: an earthen redoubt on Dawes Point, with two cannon from the Sirius. (Ironically, the first defence raised at Sydney by Europeans, a stockade and two small cannon, was actually French, mounted by La Perouse at Botany Bay, reported by Philip Gidley King). [2] By 1803, during the Napoleonic wars, and as a result of warnings from Britain of the dangers posed by French warships, the first of the harbour headland batteries was constructed at Obelisk Point (just south of Middle Head), then the most forward of the defences. [3] But soon afterwards, an artillery officer complained that the Dawes Point battery 'falls to pieces when the guns are fired'. [4] And in 1819, WC Wentworth was complaining that it was in such a bad state, and the embrasures were so low, that 'a single broadside of grape would sweep off all who had the courage or temerity to defend it'. His view was that 'a vessel of ten guns might have ... [assaulted and plundered Sydney] with the greatest of ease and safety'. [5] This kind of criticism of Sydney's defences was a constant refrain for the rest of the century.

In the following year, Commissioner Bigge assigned Major James Taylor to examine the defence of Sydney. Taylor reported that the likely landing places for invaders were Bondi Beach and Botany Bay. Bigge reported to the British Government:

Taylor was adamant that the key to the defence of Sydney was the Surry Hills. If time allowed these sandhills were to be fortified by fieldworks, redoubts and entrenchments. ... If defeated on the Surry Hills, Taylor suggested that the defenders retire on the town where the streets would be barricaded and loopholes cut in the houses, gradually retiring to a citadel which it appears was to be erected somewhere on The Rocks. [6]

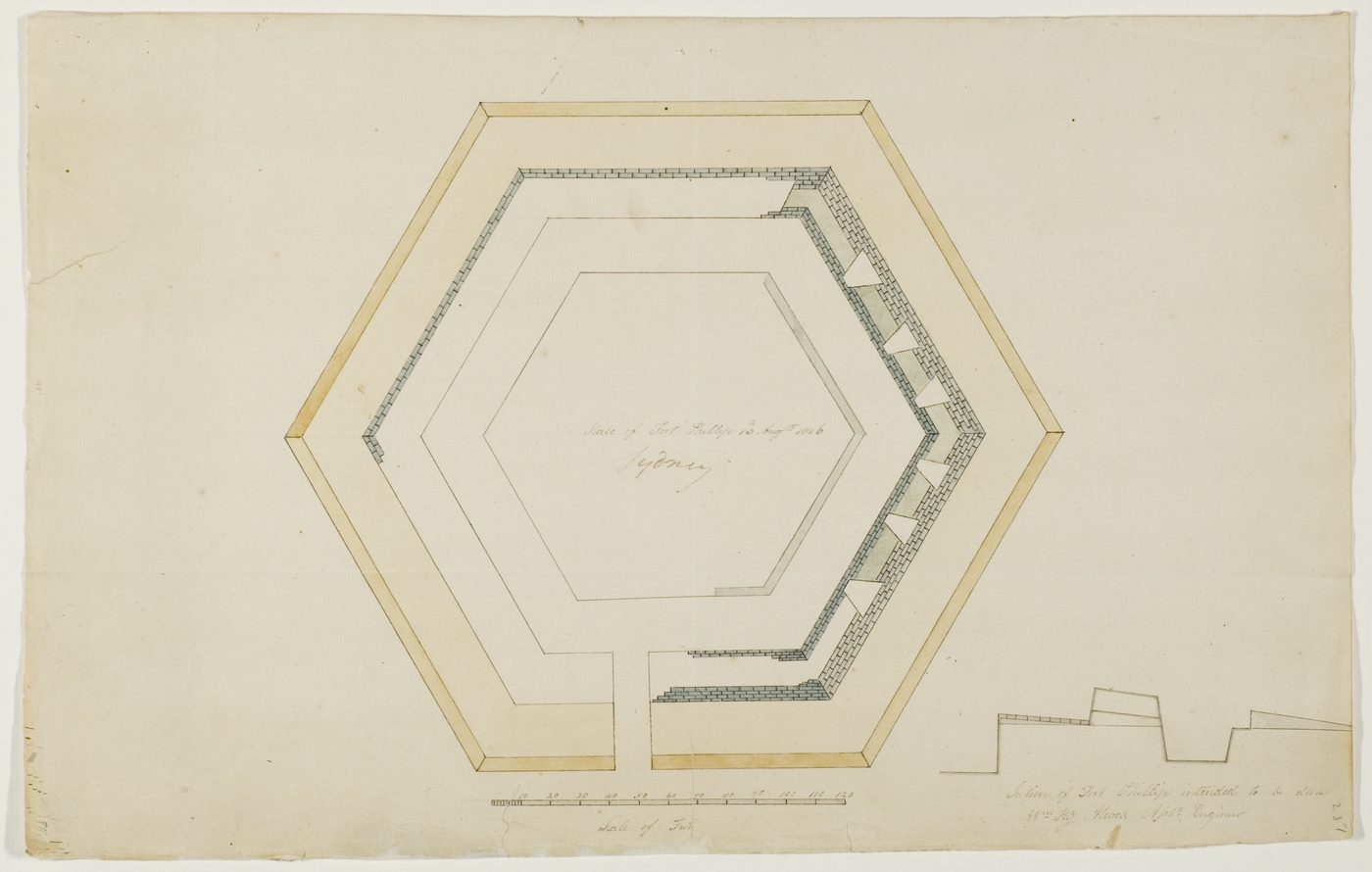

[media]The citadel of last resort is presumed to be Fort Phillip, begun in 1804 by Governor King on Windmill Hill but never completed. In Taylor's view, 'if Britain found herself at war again with the United States., the Americans would be in a good position to seize Britain's Australian colonies'. [7] Bigge also warned of the constant threat to the colony's trade in the region, and of the 'outrages of the South Seas whaling vessels'. [8] The US had by far the largest whaling fleet in the South Seas.

American ships test the defences

In December 1839, Sydney awoke to find that two American men-of-war had entered the harbour unexpectedly overnight and anchored in Sydney Cove. The fleet commander, Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, was later quoted,

If [we had been] enemies, it would have been in our power before daylight to have fired all the Shipping and store houses, laid the town under contribution and departed unhurt. [9]

The resultant outcry about the defenceless state of Sydney led to some hasty rebuilding and new harbour fortifications, on Pinchgut Island (Fort Denison) and Bradleys Head.

Even so, within only a few years calls for more effective harbour defences continued, from Britain as well as in Sydney. A correspondent to The Times in London in 1846, lamenting 'the unprotected state of our Australian possessions', pointed out that

Port Jackson (which is the finest harbour in the world) ... and the miraculous city of Sydney are left totally at the mercy of any enemy's privateers.

And what a prize Sydney offered to even an 18-gun brig holding it to ransom, 'seeing that the banks alone have at present about half a million pounds sterling in gold in their coffers'. [10] Sydney's city fathers were anxious enough to remind the Governor in 1847 that the colony, as a 'component part' of the British Empire, 'cannot but look forward to the probability of being open to attack in the first war in which the mother country may be engaged'. [11]

War in the Crimea and threats in the region

[media]Fortunately, when Britain and France declared war on Russia in 1853, no immediate attack on Sydney eventuated, but additional battery sites were ordered (later suspended) for Middle and South heads as defence against anticipated raids by the Russian Navy. [12] And not only Russia; as by now Sydney was casting an anxious eye to the near-Pacific, where France had established a colony in New Caledonia.

The outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853 – added to the perceived threat to the colony posed by the French and by American fleets in the Pacific – had rekindled more anxious government inquiries into the state of defences. Work on these had been stifled since the 1840s by more pressing concerns brought on by the Depression. A decade of European wars and forebodings of war aggravated fears of attack, because news from Europe took weeks to arrive. The colony could be at war and not know; the next ship to sail through the heads might be an enemy. Typical of the fears was the reaction to the so-called 'Trent Affair'. News of the seizure in 1861 by a US naval vessel of a British mail steamer, the Trent, took nine weeks to reach Sydney. This was a major incident which led to Britain making war preparations before the matter was resolved, but it was another month before news of the peaceful resolution reached Sydney. [13] Meanwhile, The Age, relaying to Sydney news from the steamship mail service, had declared, 'We cannot tell whether we are at peace or war with the United States'. [14]

Russian worries

Foreign ships often visited Sydney during the nineteenth century. Even when they were from a nation hostile to Britain, they were usually treated as welcome guests. That included the officers and crew of the 17-gun Russian corvette Bogatyr, which cruised quietly at midnight into Sydney Harbour in March 1863. The Russian visit created little concern until after she had gone, when it was revealed by a correspondent to the Herald that Admiral Popov, aboard the Bogatyr, had been surveying the coast. More alarmingly, it was claimed that a longboat crew from the Bogatyr had been sent down the coast to survey Botany Bay and had been picked up later when the ship sailed from Port Jackson. [15]

Another scare ensued when copies of The Times for 17 September 1864 finally arrived in Sydney. Readers learnt of an elaborate plan in the previous year for the Russian fleets on the American coast and in Japan, 'to bear down on the Australian colonies' and attack their cities. Attacking the colonies was the Russians' plan to inflict discredit on Britain if war were declared. No attacks occurred, but Russia continued to be seen as a threat. A senior officer, giving evidence before a New South Wales Legislative Assembly Select Committee, warned 'We are constantly exposed to unexpected attack through international complications involving the Mother County'. [16] He continued:

Reports [in 1863] of the contemplated descent on the Australian colonies of a Russian Fleet, bringing 200 guns and more than 3,000 men, shews us the possibility of an invading enemy's approaching our shores with the probable intention of landing troops, either to effect part of their military operations by land, or as a stratagem to lessen the resistance our forts could offer. [17]

New fortifications

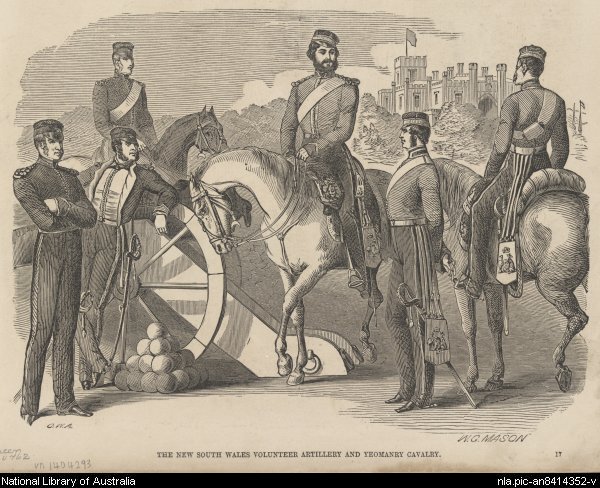

In 1870, after Britain had withdrawn the last of her Redcoat garrisons from Sydney, the government again ordered a serious re-evaluation of Sydney's harbour defences. [media]A Royal Commission decided to build batteries at Middle Head, Georges Head, South Head, Bradleys Head, and Shark Point on the harbour. These were impressive works, and as the work progressed Sydney looked proudly on its new fortifications, showing them off to important travellers. The writer Anthony Trollope commented after visiting Sydney:

I found five separate fortresses, armed, or to be armed, to the teeth with numerous guns. ... I was shown how the whole harbour and city were commanded by these guns. ... There was much martial ardour, and a very general opinion that 'they' [any attackers] would have the worst of it. [18]

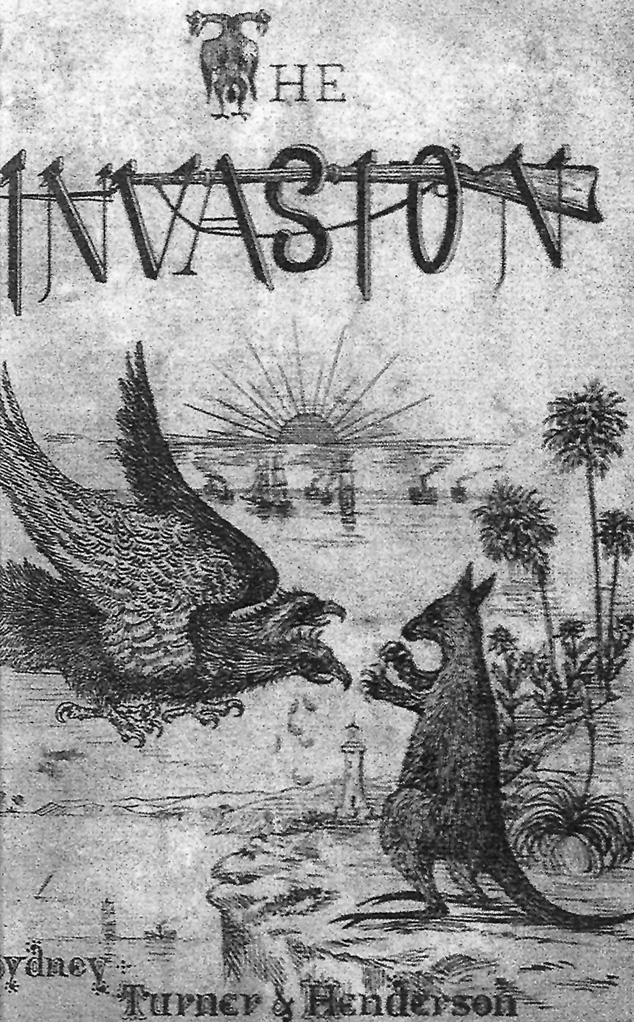

With the linking of Australia to Britain by telegraph in 1872, news of imperial brinkmanship, political manoeuvrings and war threats could reach Sydney's streets on the day it was published in London. Better communications also showed that Sydneysiders were not alone in their invasion anxieties: anxious Britons were reading a popular new literary form known as 'invasion scare novels' which usually involved the onslaught of foreign European armies taking advantage of Britain's supposed vulnerability caused by neglect of military preparedness. Soon the invasion fiction was reaching the colonies, now more than ever anxious about Britain's declining ability or willingness to come to the defence of her colonies. [media]A lively local example, The Invasion, by 'WH Walker', published in Sydney in 1877, recounted a fictional attack on Sydney by the Russians. Iron-clad Russian warships were described, standing off the heads as a diversion while a fleet of steamers debouched 6,000 troops at Botany Bay at two in the morning. Battles raged throughout the eastern suburbs and city before heroic efforts finally had the Russian invaders on the run, leaving Sydney ablaze and thousands slaughtered. [19]

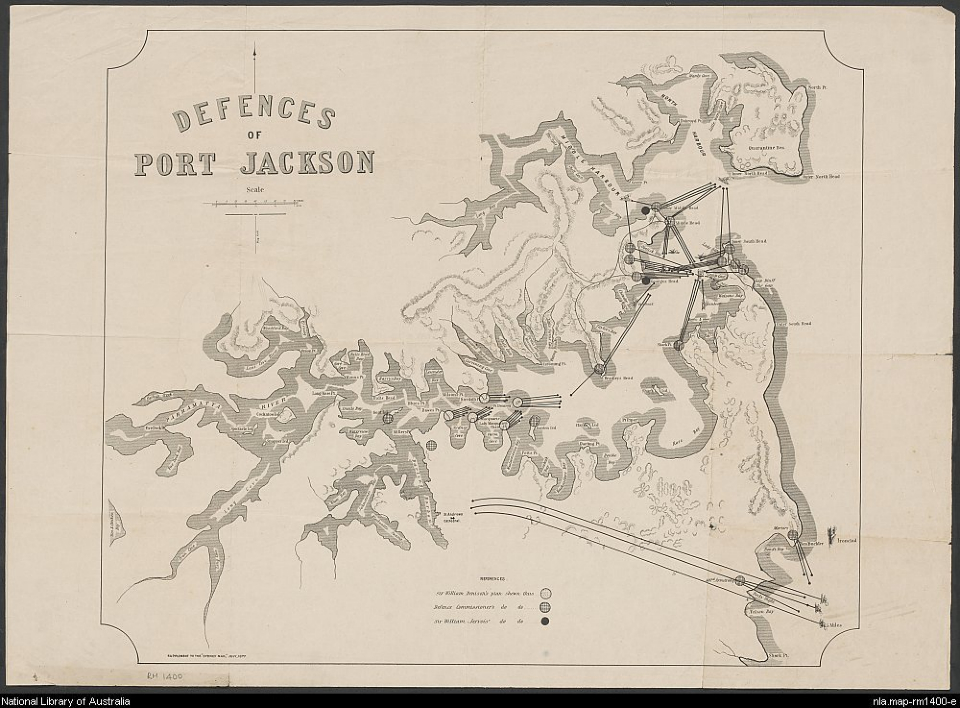

[media]Further unrest and hostilities in Europe in 1876 prompted the New South Wales government to appoint Sir William Jervois, who had been largely responsible for the reorganisation of Britain's defences, to review defences in the colony. He and Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Scratchley made far-reaching recommendations, including upgrading batteries, building new ones, modernising ordnance, and reorganising military personnel. [media]Sydney's defence was now to be based on heavy coastal guns in strong fortifications facing seaward, and the weapons guarding the entrance to the harbour were supported by minefields, gunboats and torpedo boats. Defence planners had already decided that the main defences should be positioned so as to prevent enemy ships from entering Port Jackson; the previous approach had been to allow an enemy ship into the harbour and then endeavour to destroy it. With the 'keep them out' plan, the outer defence of Port Jackson was to be centred on Middle, South and Georges Heads, with additional batteries at Bradleys Head and Steel Point. [20] On Jervois and Scratchley's advice, these batteries were improved, and larger, longer-range weapons were installed. Smooth-bore guns were replaced with rifled, muzzle-loading guns. These were able to fire elongated projectiles which could reach greater distances, with improved accuracy and penetration. Guns on the headlands could bring 'plunging fire' down on enemy ships attempting to pass into the harbour. The enemy ships would have difficulty raising their guns' elevation to fire on the headland batteries. [21]

New Russophobia

In 1885, some 200,000 people of a total Sydney population of 300,000 turned out to farewell a contingent of volunteers departing to support Britain's imperial war in the Sudan. Soon afterwards, Britain moved troops urgently to protect India's north-west frontier 'against the designs of the "Unspeakable Russian Bear"' in Afghanistan. [22] With 'Russophobia' rampant again, rumours circulated in Sydney that a Russian fleet intent of invading the colony was on its way. Under the blunt heading 'War', the Town and Country Journal explained that '[Russia's] tactics, it is believed, includes sending a flood of privateers, backed by a squadron, to loot the colonies'. But it added comfortingly, 'Britain is ready and willing, all the world over, to give her [Russia] the chastisement which her encroachments and sneaking policy so richly deserve.' [23]

'Sir Galahad', in the same newspaper, warned that 'before we are a month older [we] may possibly hear the unwelcome roar of Russian cannon along our coast'. And, looking at what he saw as the defenceless state of Sydney, he continued:

although the harbor of Port Jackson is probably amply defended with its double line of batteries and sunken torpedos, yet on the coast side, save at the South Head and La Perouse, not a solitary gun could be brought to bear against a fleet. Consequently a hostile fleet could lay at its leisure, and bombard Sydney from the safe shelter of Bondi or Maroubra bays, holding the city to ransom, or destroying it, as suited the sovereign will of its commander. Or again, a force could be landed at Coogee under cover of the ships, and seizing the water works, starve the city into submission. [24]

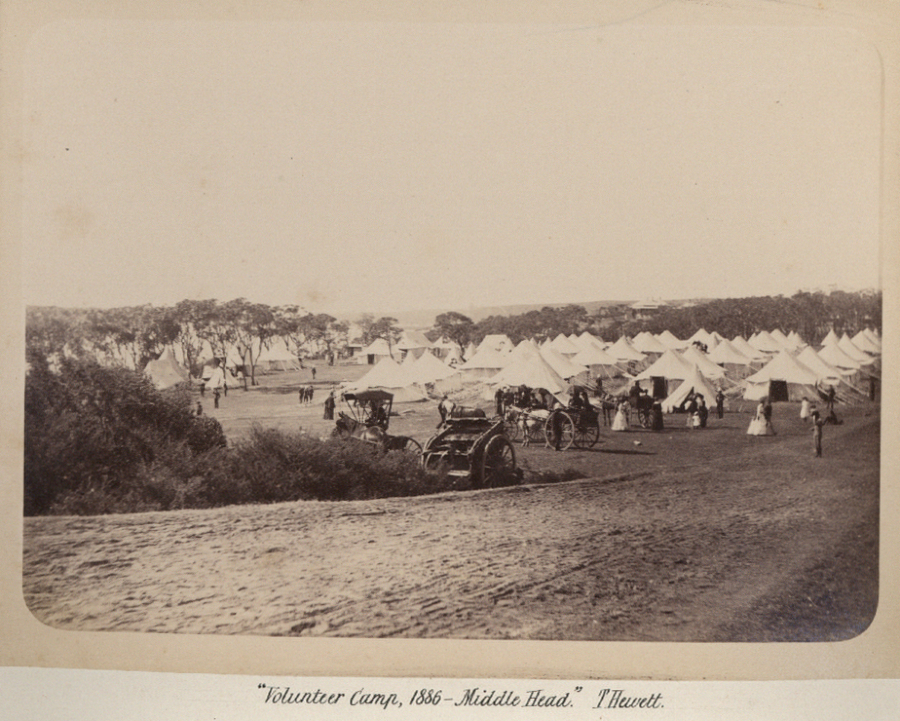

The [media]threat was taken seriously by the colonial government in Sydney. Cabinet ministers met with military and naval advisers, in what was described as a 'council of war' from 31 March 1885, and continued to meet almost daily to prepare a complete plan of defence for the coast and chief harbours. [25]

Cliff defences in difficult times

The 1890s marked a major change in Sydney's defence. Larger, heavily armoured iron-clad warships, with longer-range guns, were coming into service and needed to be taken into account. Different tactics were applied, with the introduction of larger breech-loading guns. These guns could be installed on the eastern suburbs' ocean cliffs to provide counter-bombardment fire. [26] Thus the 9.2-inch (234 mm) calibre breech-loading guns on hydro-pneumatic mountings – so-called 'disappearing' guns because they could be raised to fire and lowered to reload in their fortified pits – were commissioned in new fortresses at Ben Buckler (Bondi), Signal Hill (Vaucluse) and Shark Point (Little Coogee/Clovelly). These guns had a range of more than 16 kilometres. They could counter-attack ships approaching the harbour or attempting to bombard Sydney offshore from Bondi or Coogee bays. [27] Further defences, at Bare Island and Henry Head, protected Botany Bay – thought to be a target for invasion since 1820. [28]

Ben Buckler's disappearing gun

The first of the big coastal counter-bombardment guns was delivered to Ben Buckler, on the cliffs north of Bondi, in April 1893. It was no easy task. A Sydney Mail report said that, owing to the steepness and bad condition of the tracks, 35 horses were needed to drag the 20-tonne gun barrel, and when the wheels of the trolley sank deep into the ground a crane had to be employed. [29] The gun was taken along the Old South Head Road towards the lighthouse and then back in a zig-zag route towards Ben Buckler. The operation took almost four weeks from Victoria Barracks.

'When in position, the gun will be able to pay considerable attention to any man-of-war attempting to bombard the city off Bondi,' was the opinion of a correspondent to the Sydney Illustrated News , but the danger was that it would take too many troops to guard it. [30] The same year, the two other coastal batteries, Coogee (or Shark Point) Fort at Clovelly, and Signal Hill Fort at Vaucluse, were completed with the same guns.

These deadly sentinels, cast in 1891, remained in their steel and concrete casements cut into the sandstone of the eastern seaboard cliff-tops for at least 65 years. They were manned at the outbreak of World War I in 1914, and mobilised briefly again in 1918 in response to suspected activities by two German raiders on the coast. [31] Although obsolete by the outbreak of World War II, the guns remained listed, probably in reserve, as part of the encompassing Sydney Fortress scheme. [32] The Ben Buckler gun, with its hydro-pneumatic mechanism, is believed to be still buried in its concrete fortress, a valuable relic of nineteenth-century defence technologies preserved under a playing field. [33]

With the Depression of the 1890s and a large cut in military expenditure, there was continual outrage in the Sydney press about the state of defence and reduction in artillery forces. Typical was a letter to the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, in which 'Cassandra' prophesied alarmingly,

We are at the mercy of a raiding force of Russians, Chinese, and Japs, who [could] seize, say, one of these half-manned batteries and turn the guns on to Sydney. [34]

A Royal Commission appointed to inquire into the military service in 1892 had reported that Sydney was particularly liable to surprise attack. It warned that Sydney's land forces amounted to just 1,370 infantry, available 'to prevent surprise landings destroying the new coast batteries near Bondi, or a disembarkation in force in Botany Bay'. [35]

The end of Fortress Sydney

Sydney struggled with spiralling public debt and austerity budgets at the end of the century, still concerned with forebodings of vulnerability and a growing danger to the north. Federation of the Australian colonies was on the horizon, and with it came hopes of a sound mutual defence system. But Sydney was about to enter a new century in which, for the first time, it would actually be attacked – from inside the harbour and offshore from Bondi – and its defences put to the test when Japanese submarines attacked in 1942. And after the two world wars, and finally peace, Sydney's big guns and forts would become redundant, overtaken by proven new technologies of bombers, missiles and nuclear weapons. [media]What was left was sold as scrap or now gently moulders in parklands that became available because there was no military reason to continue maintaining Fortress Sydney.

References

Dean Boyce, Invasion: Colonial Sydney's Fear of Attack, the author, Waverley NSW, 2008

Frank Doak and Jeff Isaacs, Australian Defence Heritage: The buildings, establishments and sites of our military history that have become part of the national estate, Fairfax Library, Sydney, 1988

Norman Ferris, The Trent Affair: A diplomatic crisis, University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, 1997

Jeffrey Grey, A Military History of Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999

Roy Harvey (ed), The Guns of Middle Head, George's Head and George's Heights, Royal Australian Artillery Historical Society, Manly NSW, 1985

Roy Harvey, North Head Battery: A brief history, Royal Australian Artillery Historical Society, Manly NSW, 1991

Roy Harvey, Sydney Harbour Fortifications Archival Study, Part Two (final report), NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Sydney, 1985

John Mordike, An Army for a Nation: A history of Australian military developments 1880–1914, Allen & Unwin with Directorate of Army Studies, Department of Defence, Canberra, 1992

Bob Nicholls, Colonial Guns, Australian Military History Publications, Loftus NSW, 1998

Bob Nicholls, The Colonial Volunteers: The defence forces of the Australian colonies 1836–1901, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1988

Peter Oppenheim, The Fragile Forts: The fixed defences of Sydney Harbour 1788–1963, Australian Military History Publications, Loftus NSW, 2005

Clem Sargent, The Colonial Garrison 1817–1824, TCS Publications, Canberra, 1996

Luke Trainor, British Imperialism and Australian Nationalism: Manipulation, conflict and compromise in the late nineteenth century, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1994

WH Walker, The Invasion, Turner and Henderson, Sydney, 1877

Notes

[1] Peter Oppenheim, The Fragile Forts: The Fixed Defences of Sydney Harbour 1788–1963, Australian Military History Publications, Loftus, NSW, 2005, p xv

[2] M Austin, 'The Early Defences of Australia', in Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 49, part 3, November 1963, p 190; Jonathan King, Philip King: A Biography of the Third Governor of NSW, Methuen Australia, Sydney, 1981, p 34

[3] Frank Doak & Jeff Isaacs, Australian Defence Heritage, Fairfax Library, Sydney, 1988, p 15

[4] Captain JH Watson, 'Sydney's Defences', Daily Telegraph, 19 May 1914

[5] WC Wentworth, A Statistical, Historical and Political Description of the Colony of NSW, Second edition, London, 1820, p 46

[6] Commissioner JT Bigge, 'Memo of information [on] the mode of defending the Capital of the Colony of NSW from outward attack', March 1820, Bigge Report Appendix, p 10

[7] Commissioner JT Bigge, 'Memo of information [on] the mode of defending the Capital of the Colony of NSW from outward attack', March 1820, Bigge Report Appendix, Bigge on Taylor's evidence, p 5

[8] JT Bigge, Report of the Commissioner of Inquiry, on the State of Agriculture and Trade in the Colony of New South Wales, Australiana Facsimile Edition No 70, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1966, p 60

[9] William Morgan et al (eds), Autobiography of Rear Admiral Charles Wilkes, US Navy 1798–1877, Naval History Division, Dept of the Navy, Washington, 1978, pp 437, 445

[10] The Times, 25 June 1846, p 6

[11] Memorial to the Governor from the Mayor, Aldermen and Councillors of the City of Sydney, 4 November 1847, Colonial Secretary Special Bundle: Defence Reports 1840–55 State Records NSW, 4/11552

[12] GC Wilson, 'Sydney Harbour Fortifications Archival Study', part 1, unpublished report to NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, 1985, p 1.4

[13] The Times, 28 November 1861, p 9

[14] The Age, 17 January 1862, p 4

[15] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 April 1863, p 8

[16] NSW Legislative Assembly, Minutes of Evidence, Select Committee on Harbour Defences, Appendix to evidence by Gustave Morell, 19 May 1865, p 2, Colonial Secretary NSW Defence Papers 1858–91, State Records NSW, 4/7054 A

[17] NSW Legislative Assembly, Minutes of Evidence, Select Committee on Harbour Defences, Appendix to evidence by Gustave Morell, 19 May 1865, p 2, Colonial Secretary NSW Defence Papers 1858–91, State Records NSW, 4/7054 A

[18] Anthony Trollope, Australia, first published 1873; PD Edwards & RB Joyce, eds, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Qld, p 232

[19] WH Walker, The Invasion, Turner and Henderson, Sydney, 1877

[20] Roy Harvey, The Guns of Middle Head, Georges Head and Georges Heights, Royal Australian Artillery Historical Society, Manly NSW, 1985, p 5

[21] Roy Harvey, The Guns of Middle Head, Georges Head and Georges Heights, Royal Australian Artillery Historical Society, Manly NSW, 1985, p 5

[22] Verity Fitzhardinge, 'Russian Naval Visitors to Australia, 1862–1888', in Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 52, part 2, June 1966, p 154

[23] Town and Country Journal, 11 April 1885, p 746

[24] Town and Country Journal, 4 April 1885, p 691

[25] Town and Country Journal, 18 April 1885, p 798

[26] Roy Harvey, The Guns of Middle Head, Georges Head and Georges Heights, Royal Australian Artillery Historical Society, Manly NSW, 1985, p 5

[27] Roy Harvey, The Guns of Middle Head, Georges Head and Georges Heights, Royal Australian Artillery Historical Society, Manly NSW, 1985, p 5

[28] GP Walsh and DM Horner, 'The Defence of Sydney in 1820', in Army Journal, no 240, May 1969, p 14

[29] The Sydney Mail, 22 April 1893, p 813

[30] Illustrated Sydney News, 15 April 1893, p 14

[31] Peter Oppenheim, The Fragile Forts: The Fixed Defences of Sydney Harbour 1788–1963, Australian Military History Publications, Loftus, NSW, 2005, p 199

[32] Peter Oppenheim, The Fragile Forts: The Fixed Defences of Sydney Harbour 1788–1963, Australian Military History Publications, Loftus, NSW, 2005, p 287

[33] NSW Heritage Council report 'Ben Buckler Gun Battery 1893', database 5056455, file H05/00100/1

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, 12 March 1892, p 4

[35] Report of the Royal Commission appointed to Inquire into the Military Service of New South Wales, appointed June 10, 1892, p 17, in NSW Legislative Assembly Votes and Proceedings, 1892/1893

.