The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Elizabeth Agnes Miller

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Elizabeth Miller

Like so many other convicts transported to Australia's penal colonies, very little is known of Elizabeth Agnes Miller. A baker's wife and matriarch in Parramatta in the early nineteenth century, Miller's early years were far from respectable.

Early life

From later records of her life, Miller's birth year can be estimated as 1794, [1] most likely in England, where in 1812 she was convicted of larceny and incarcerated for three months in Middlesex County. [2] In 1818 she was apprehended in Lambeth by constable George Goff in possession of £3 worth of forged Bank of England paper notes. [3] At the time of this offence, Miller was a mother to a five-year-old daughter named Rebecca. For her £3 crime she received a 14-year sentence while the constable responsible for her arrest was rewarded the handsome sum of £20 from the Bank of England for his act of law enforcement. [4]

Conviction

By order of the Bank of England's Committee for Law Suits which had convened and discussed the case of Elizabeth Miller on 2 July 1818, [5] Miller was prosecuted for 'possession of forged bank notes' on 6 August 1818 at the Surrey Summer Assizes. [6] Three others were tried that day for the same offence: 18-year-old Jane Wilson, [7] 23-year-old Charles Scott, a leather draper by trade, [8] and William West. [9] Their sentences differed immensely. West had been discovered with £53 of counterfeit notes and had attempted to dispose of the parcel containing them to conceal his guilt. For this, he hanged. Had the four forgers committed their crimes 17 years earlier when possessing counterfeit notes was automatically a capital offence for all, West would not have gone to the gallows alone. [10] Miller, Wilson, and Scott accepted the newly introduced option of a plea bargain instead; admitting their guilt spared their lives but condemned them to 14 years transportation.

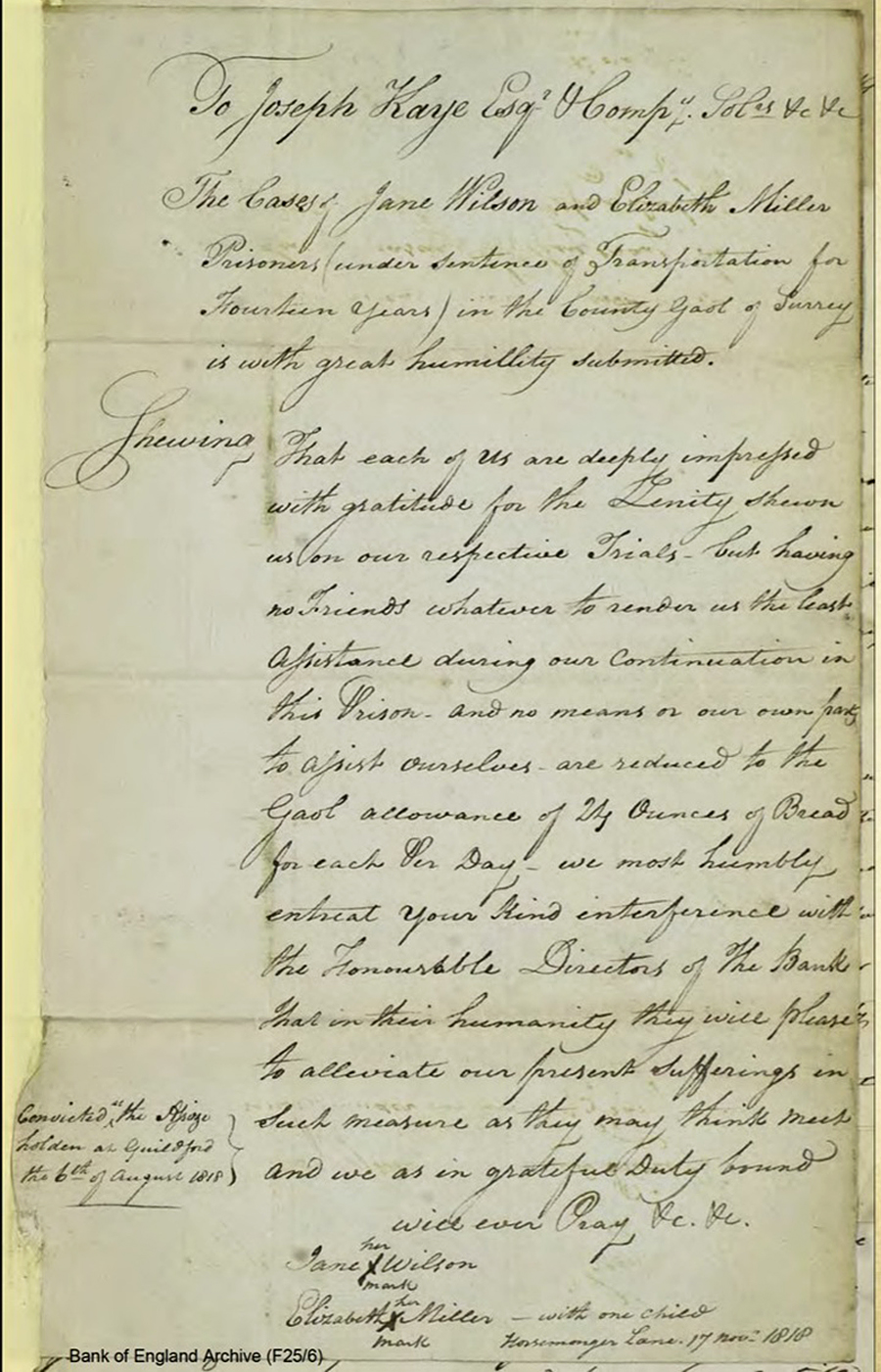

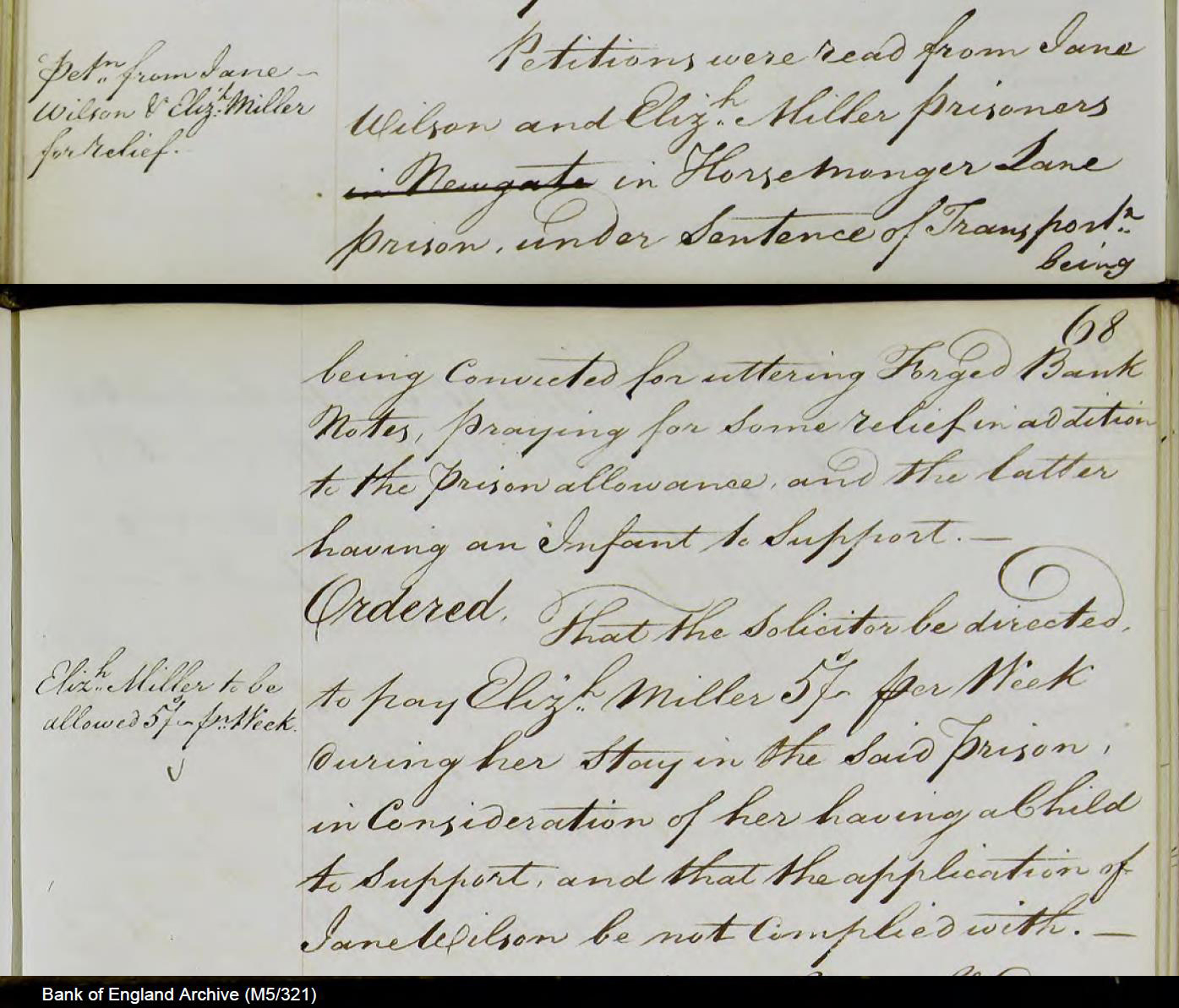

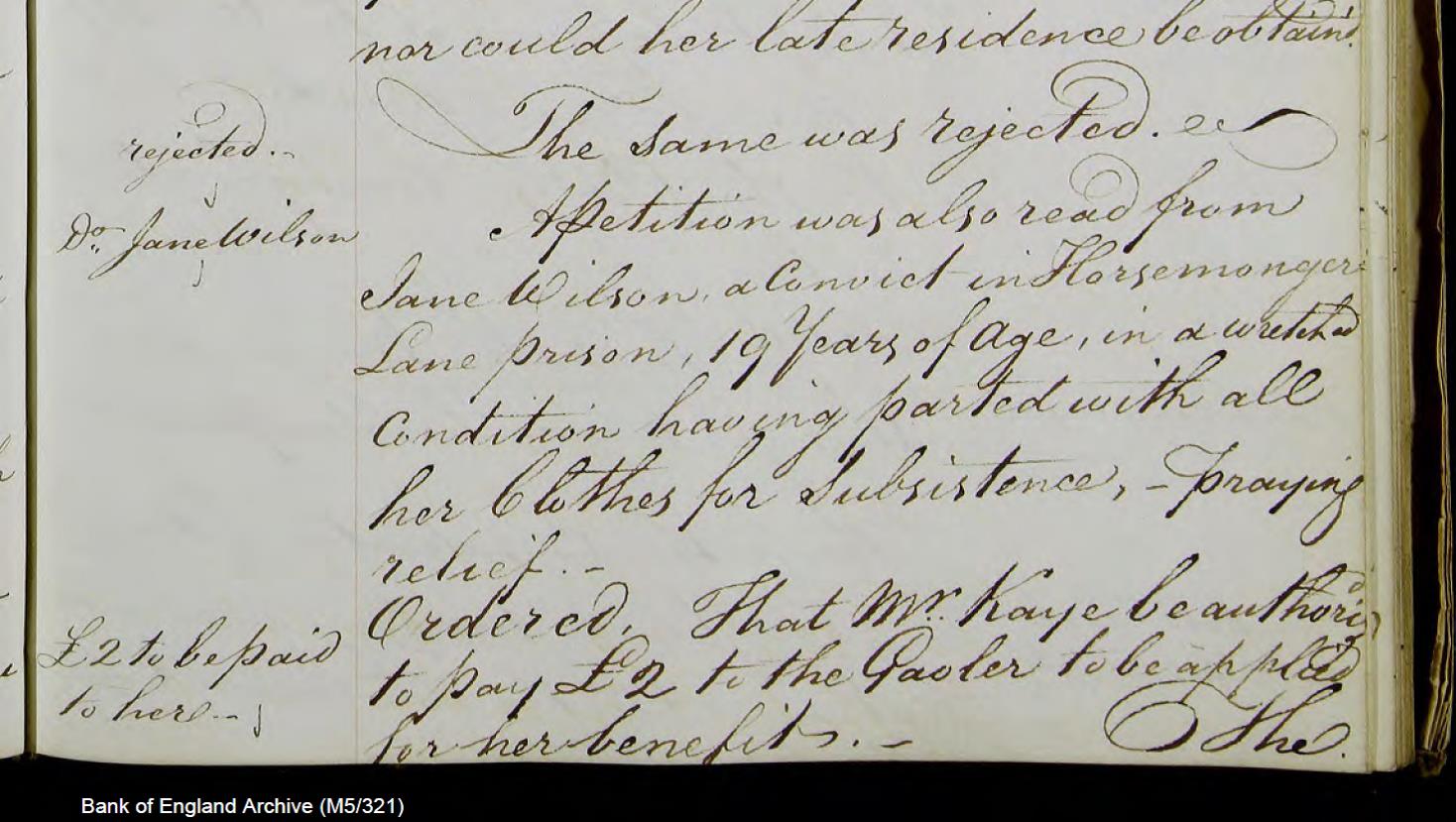

[media]While awaiting transportation, Miller and Wilson were held in the Surrey County Gaol in Horsemonger Lane, Southwark. By November 1818, the conditions of the gaol were so unbearable that an unknown person wrote a letter on behalf of Miller and Wilson to Joseph Kaye Esq, the Bank's solicitor, [11] requesting monetary assistance from the Bank's 'Honourable Directors.' [12] Many letters like this were penned between 1781 and 1827, seeking aid from the very bank the prisoners had acted feloniously against, and the Bank of England did sometimes provide such petitioners with relief, especially to women with children. [13] Elizabeth's petition for relief was granted 'in consideration of her having a child to support,' [14] however, her childless co-petitioner, Wilson, was denied. [15] [media]A few months later, [media]Wilson was transported to New South Wales on the Lord Wellington [16] while Elizabeth and her five-year old daughter Rebecca had to endure another five months in prison with charitable assistance from the Bank of England to the value of five shillings per week. [17]

Transportation

Elizabeth and Rebecca made the arduous passage to the colony of New South Wales along with 104 other female convicts on the notorious ship the Janus, departing on 23 October 1819. [18] Whereas many convict ships were infamous for considerable loss of life due to disease and shipwreck, the cause of the Janus's infamy was quite the contrary; upon arrival in Sydney on 3 May 1820, [19] the ship's population had multiplied, owing to the number of female convicts found to be pregnant to crew members as a result of prostitution on the ship. [20] The ship's captain, Thomas Mowat, adamantly claimed to have fastened 'evening hatches' to prevent sailors and women from interacting at night, and Corporal Moore's wife, Ann, claimed never to have observed 'more between the Sailors and female Convicts, excepting seeing them walk about the Decks.' [21] Nevertheless, the high pregnancy rate indicates the Janus, like a number of other all-female convict ships, was nothing short of a floating brothel. Testimonies by two Catholic priests on board confirm that the security of the hatches and locks preventing nocturnal visits were easily and regularly bypassed and prostitution was not only well known to the superiors aboard the ship but they were the worst and most common offenders, with 'two or three women often, indeed Constantly, in the captain's Cabin.' [22]

Marriage

With a child in tow, Miller would most likely have been sent to Parramatta's first Female Factory, the 'factory above the gaol,' on arrival in the colony, rather than being assigned to a master. At the time of her arrival, construction of the second Female Factory was incomplete and the first factory was inadequate as a refuge due to the overwhelming and ever-increasing number of women requiring work and accommodation. Many women in Miller's position –even without a child to care for – were, at worst, forced to prostitute themselves to obtain funds, cohabit with men for shelter and other basic necessities or, at best, make a speedy marriage of convenience.

It is not surprising, then, to find that a mere two months after her arrival in the colony, 26-year-old Elizabeth agreed to marry fellow convict, 34-year-old William H Bennett. In July 1820, Bennett was based in Parramatta and may have already obtained his ticket of leave which, according to a later convict muster, he had by 1822. [23] The ticket of leave allowed Bennett certain freedoms including the ability to work for himself long before his certificate of freedom was received at the expiration of his sentence in October 1824. [24] Upon receiving the Governor's permission to wed, [25] Miller and Bennett married at St John's Anglican Church, Parramatta in 1820 [26] and Bennett assumed the role of stepfather and guardian to Rebecca. [27]

Servitude and childbirth

The earliest years of Elizabeth's life as an assigned convict are unclear, [28] but we know that from 1825 she served part of her 14-year sentence as a servant to Matthew 'Matt' Miller [29] a widowed constable and pardoned convict living at Windsor [30] who had two children. [31] Elizabeth’s assignment to Miller at this time would be significant for several reasons, not the least being Miller's brutal bashing of his new wife in 1828, for which he was condemned to hang. [32]

During Elizabeth's time as Miller's servant at Windsor, it seems she had a child with his friend and colleague, George Jilks. Birth records show that a child named 'William Bennett Jilks' was born at Windsor on 9 October 1826 to George Jilks, Chief Constable of Sydney, and a woman recorded only as 'Elizabeth' [33] – the name of Jilks's spouse was 'Maria,' while the name of Elizabeth's husband was 'William Bennett.' What is particularly noteworthy, however, is that William Bennett Jilks may not have been the couple's sole issue and, even more surprisingly, may not have been their first.

Years later during a court case involving his god-daughter Rebecca Miller, Jilks stated under oath that he had known Elizabeth in England, well before either of them were convicted and transported, and even claimed to have known her daughter Rebecca 'from her birth.' [34] His claims were plausible, since Jilks was tried and convicted as 'George Gilkes' in Middlesex, [35] close to where Elizabeth herself was apprehended for her crime. Jilks, rather tellingly, also protested – perhaps too much – under cross-examination,

I have been called the father of [Rebecca], but I am not; I swear I am not; she never went by any other name than Bennett in this colony; she never went by my name....Robert Miller is her father, who, I believe, is now alive in England; he married my sister, but she is not the mother of [Rebecca]; Mrs. Bennett is her mother... [36]

Thus far, no records of Jilks's English sister or her husband Robert Miller have been located to corroborate Jilks's story. It is possible Jilks fabricated these facts to conceal the reality of Elizabeth and Rebecca's former lives in England to avoid sullying their reputation as fine upstanding citizens of Parramatta. Indeed, one newspaper reported that Rebecca 'and her family walked in the middling class of society, & enjoyed a fair fame among their numerous friends.' [37] Suspicions regarding Jilks's links to Elizabeth and Rebecca were raised further when Jilks's wife, Maria, [38] was cross-examined and she paused significantly before replying to the question of whether she had ever referred to Rebecca as Miss Jilks: 'I might, perhaps, have called her so, at my own house, when talking to the children, but never since she has grown up.' [39]

With Rebecca's birth year estimated as 1813 and Jilks's conviction in September 1814 and transportation in May of 1816 on the Mariner , [40] Jilks could have been her biological father as others had obviously insinuated. The court case revealed that the people who knew the families well not only entertained the idea that Jilks was Rebecca's father but also voiced this theory, indicating it was already common knowledge that Jilks and Elizabeth had a child together in Windsor. Evidently, the connection between the Jilks and Bennett families was always strong because a six-year-old girl named 'Margaret,' a daughter of George Jilks, was a resident at Bennett's bakery at the time the 1828 census was taken. [41]

Married life

Despite having been married since 1820, the Bennetts did not have their first child together until 1829; a daughter christened Elizabeth Ann followed by a son, William H Bennett Jnr, born circa 1831 at Bennett's Parramatta home and bakery. [42]

Elizabeth was roughly 38 years old when her 14-year sentence was due to expire in August 1832. While tickets of leave and certificates of freedom were published in the newspaper from around 1825 onwards, to date, no record of her emancipation has been recovered there or in the official records.

Two months prior to what should have been her emancipation date, Elizabeth's husband brought a court case against St John's Tavern publican Thomas Brett for leaving her daughter Rebecca a jilted bride. In addition to revealing Jilks as the likely father to Elizabeth’s daughter Rebecca, the court proceedings revealed that the Bennetts were wealthy enough in 1832 to have spent £1,000 on a wedding for Rebecca that never eventuated. [43] Clearly, Elizabeth's life had changed vastly since the day she had been apprehended for the comparatively paltry sum of £3 and had to pray and beg the Bank of England for some charity while she was incarcerated with the infant Rebecca on Horsemonger Lane.

[media]The significant change in fortune Elizabeth enjoyed was due to the success of her husband, William. In spite of his convict beginnings, by the time he was emancipated in October 1824 Bennett had already established himself as a baker and had made enough headway to set up his home and business at the three heritage-listed Georgian cottages on the corner of O'Connell and Hunter Streets, later known as the Travellers' Rest. In a few short years, he was looked upon as one of the town's eminent and respectable bakers and landowners [44] and was even master to a number of convicts, including Charles Stephens and John Davis, who were assigned to labour in his bakery. [45]

[media]In spite of the breach of marital promise committed by the 'fickle swain' [46] Thomas Brett against Rebecca, Elizabeth lived to see both her daughters married. However, on 19 October 1847, just seven months after the wedding of eighteen-year-old Elizabeth the younger to Charles Smith, commander of the Woodlark, [47] Elizabeth the elder, 'the beloved wife of Mr William Bennett' passed away in her fifties, 'leaving a disconsolate husband and family to deplore their loss.' [48] Her final resting place was St John's Cemetery, Parramatta, located on the same street as the Bennetts' home and bakery. Thirteen years after her death, her burial plot also became the final resting place for her husband. [49]

References

Ancestry.com

Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes. London: Bank of England, 1802–1908. Archive Number: M5/307–342. http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Pages/digita lcontent/archivedocs/commlawsuits/commlawsuits.aspx. Viewed 20 August 2014.

Freshfields Prison Correspondence. London: Bank of England, 1781–1840. http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Pages/digita lcontent/archivedocs/freshfields.aspx. Viewed 20 August 2014.

Freshfields Papers: Prison Correspondence. London: Bank of England, 1818–1820. Archive Number: F25/6/36.

Damousi, Joy. Depraved and Disorderly: Female Convicts, Sexuality and Gender in Colonial Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Dunn, Judith. The Parramatta Cemeteries: St. John's. Parramatta: Parramatta and District Historical Society, 1991.

Home Office. Criminal Registers, Middlesex. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK.

Home Office. Criminal Registers, England and Wales. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK.

Proceedings of the Old Bailey. London's Central Criminal Court, 1674–1913. http://www.oldbaileyonline.org. Accessed 15 August 2014.

Richards, J. The Legal Observer, Or, Journal of Jurisprudence. London: Edmund Spettigue, 1841, 21.

1828 Census: Householders' Returns. Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales. Parramatta Series: NRS 1273, Reel: 2507.

Notes

[1] This backdated age is based on the age recorded in the 1828 census. It conflicts with the age recorded in her death notice in the newspaper, (56 years), which would make her approximate year of birth 1791. 1828 Census: Householders' Returns (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), 65, Parramatta Series: NRS 1273, Reel: 2507

[2] 'Elizabeth Miller,' Home Office Criminal Registers, Middlesex and Home Office: Criminal Registers, England and Wales, (Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK), 133, Series HO 26 Piece 48; Date of Trial: 28 February 1812; Place of Trial: Central Criminal Court, Middlesex England; Sentence: Imprisonment.

[3] 'Elizabeth Miller apprehended at Lambeth having 3 forged notes of £1 each in her possess.n Ordered that she be prosecuted.' Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes, 1818, Book 2 (London: Bank of England) 173, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Documents/archivedocs/commlawsuits/18161825/cls0705181827081818b2.pdf, viewed 20 August 2014

[4] For list of 'Convicts from the Summer Assizes 1818' and 'Persons for Rewards' see Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes, 1818–1819, Book 1 (London: Bank of England, 1818) 9, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Documents/archivedocs/commlawsuits/18161825/cls0309181828011819b1.pdf, viewed 20 August 2014

[5] Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes, 1818 Book 2 (London: Bank of England, 1818) 173, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Documents/archivedocs/commlawsuits/18161825/cls0705181827081818b2.pdf, viewed 20 August 2014

[6] 'Elizabeth Miller,' England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791–1892 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009), 1249, Class HO 27 Piece 16; 'Elizabeth Miller,' Australian Convict Transportation Registers – Other Fleets & Ships, 1791–1868 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007), , Class HO 11 Piece 3

[7] 'Jane Wilson: Jane Wilson for uttering 1 forged note at £1 pound at [London] and having two others taken out of her mouth. Ordered that...Jane Wilson be prosecuted, with liberty to plead guilt to the minor offence,' see Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes, 1818 Book 2 (London: Bank of England, 1818) 14–12, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Documents/archivedocs/commlawsuits/18161825/cls0705181827081818b2.pdf, viewed 20 August 2014

[8] New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806–1849 (Provo, UT: USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007), Class HO 10 Piece 43; Charles Scott, originally a leather draper of Horsely Down, Bermondsey, London England; see Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes, 1818, Book 2 (London: Bank of England, 1818), 173; for discussion of his case by the Committee for Law Suits recommending his prosecution and that he should be allowed to plead guilty to the minor offence, see Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes, 1818, Book 2 (London: Bank of England, 1818), http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Documents/archivedocs/commlawsuits/18161825/cls0705181827081818b2.pdf, viewed 20 August 2014. Scott was transported per Surrey on 29 September 1818, arrived in 1819 and was assigned to 'public works' in Tasmania. His certificate of freedom was granted 29 November 1832 and he married a convict named Mary Williams in Hobart in 1835.

[9] 'William West: Wm. West apprehended at Barnes Surry for uttering 4 forged bank notes of £1 each, and having in his possession 2 others of £5 each and 39 of £1 each were found in a parcel supposed to have been thrown away by him, as the said notes exactly corresponded with those uttered by him. Ordered to be prosecuted,' Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes, 1818, Book 2 (London: Bank of England, 1818), 182, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Documents/archivedocs/commlawsuits/18161825/cls0705181827081818b2.pdf, viewed August 2014; Regarding the outcome of his trial, see England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791–1892 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009), 1247–9, Class HO 27 Piece 16,

[10] Since the 1600s it was a capital offence to forge Bank of England paper notes and by the 1700s even the act of knowingly circulating them – a practice known as 'uttering' – carried a death sentence. Sentencing for this offence was extreme in order to quash the epidemic of counterfeit notes that had swept the country in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars. However, in May 1801, with a high number of hangings already recorded for the crime of forgery and the recent introduction in 1797 of low denomination notes valued at only one and two pounds, the Bank of England legally introduced a plea bargain to differentiate between major and minor offences. Miller, Wilson, and Scott appear to have saved themselves from the gallows pole by taking advantage of this option. Admitting their guilt though, they knew, automatically condemned them to fourteen years transportation.

[11] 'Scotland,' Glasgow Herald, Friday, 27 July 1827, 8; J Richards, The Legal Observer, Or, Journal of Jurisprudence, Volume 21 (London: Edmund Spettigue, 1841) 394

[12] 'Petition of Jane Wilson & Eliz.th Miller, in Horsem. Gaol, for relief,' Freshfields Papers: Prison Correspondence 1818–1820 (London: Bank of England), http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Documents/archivedocs/freshfields/fpc18181820.pdf, viewed 20 August 2014

[13] Freshfields Papers: Prison Correspondence 1781–1840 (London: Bank of England), http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Pages/digitalcontent/archivedocs/freshfields.aspx, viewed 20 August 2014

[14] Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes 1818–19, Book 1 (London: Bank of England) 67–8, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Documents/archivedocs/commlawsuits/18161825/cls0309181828011819b1.pdf, viewed 20 August2014

[15] A decision which forced Wilson to part 'with all her clothes for subsistence' over the coming months until the committee acknowledged her 'wretched condition' in January 1819 and ordered Mr Kaye to authorise the payment of two pounds 'to the Gaoler to be applied for her benefit. Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes, 1818–1819, Book 1 (London: Bank of England, 21 January 1819), 120, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Pages/digitalcontent/archivedocs/commlawsuits/commlawsuits.aspx, viewed 20 August 2014

[16] 'Jane Wilson,' Australian Convict Transportation Registers – Other Fleets & Ships, 1791–1868 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007)

[17] Bank of England Committee for Law Suits Minutes 1818–1819, Book 1 (London: Bank of England) 67–8 http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Documents/archivedocs/commlawsuits/18161825/cls0309181828011819b1.pdf, viewed 20 August 2014

[18] 'Elizabeth Miller,' Australian Convict Transportation Registers–Other Fleets & Ships, 1791–1868 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007)

[19] 'Elizabeth Miller,' New South Wales, Australia, Settler and Convict Lists, 1787–1834 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007); 'Elizth Miller,' New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806–1849 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007); 'Elizabeth Miller,' New South Wales, Australia Convict Ship Muster Rolls and Related Records, 1790-–1849 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008); 'Elizabeth Miller,' New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788–1842 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2011)

[20] Joy Damousi, Depraved and Disorderly: Female Convicts, Sexuality and Gender in Colonial Australia, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 9–18

[21] Joy Damousi, Depraved and Disorderly: Female Convicts, Sexuality and Gender in Colonial Australia, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 10

[22] Joy Damousi, Depraved and Disorderly: Female Convicts, Sexuality and Gender in Colonial Australia, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 11–12.

[23] 'William Bennett,' New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806–1849 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007), Vessel: Tottenham; Year 1822. The convict muster for 1822 indicates William Bennett had a ticket of leave and his occupation as 'baker,' but since it does not indicate when he received his ticket of leave, it is possible he had it much earlier and was already setting himself up as a baker as early as 1820 when he was requesting permission from the Governor to marry Elizabeth.

[24] Bennett's certificate of freedom was issued 21 October 1824, New South Wales, Australia, Certificates of Freedom, 1810–1814, 1827–1867 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009);See also the listing of William Bennett as recipient of his certificate of freedom in 'Public Notice,' The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 28 October 1824, 1

[25] 'Elizabeth Miller,' New South Wales, Australia, Colonial Secretary's Papers, 1788–1825 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010), 107, Series NRS 937, Item 4/3502

[26] Australia Marriage Index, 1788–1950 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010), Registration Year: 1820; Registration Place: Parramatta, New South Wales, Volume Number: V A

[27] The Convict Musters for 1822 and 1825 list Rebecca as 'Rebecca Bennett' and that she is his daughter. 'Bennett: General Muster,' (1822), New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806–1849 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007); 'Rebecca Bennett: General Muster A–L,' 1825, New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806–1849 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007)

[28] In 1822, under the 'By whom or where employed' column on the convict muster, it merely states 'Wife of Wm. Bennett, Parramatta,' 'Elizabeth Miller: General Muster,' 1822, New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806–1849 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007)

[29] 'Elizabeth Miller', General Muster, 1825 in New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806–1849 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007); 'Matt Miller', New South Wales, Census and Population Books, 1811–1825 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2014), Population Book, 1814

[30] Muller was of no relation to Elizabeth as his colonial appellation was an Anglicised version of his German name, Matthias Muller. 'Mathias Miller', General Muster, 1811 in New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806–1849 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007); 'Matthias Miller,' July 1820, Memorials to the Governor 1810–1825, Colonial Secretary's Papers, 1788–1825 (New South Wales, Australia: State Records of New South Wales), Series: NRS 899, Item: 4/1824B; Number: 496, Page: 838

[31] 'Matthew Miller; Alice Maurice,' 1814, Australia Marriage Index, 1788–1950 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010), Marriage Place: New South Wales; Registration Place: Windsor, New South Wales, Volume Number: VA; 'Joseph Miller,' 1815, Australia Birth Index, 1788–1922 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010), Registration Place: Windsor, New South Wales; Volume Number: V18153710 1B; 'Jane Miller,' 1817, Australia Birth Index, 1788–1922 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010), Registration Place: Sydney, New South Wales; Volume Number: V18174498 1B; 'Alice Miller,' 1823, Australia Death Index, 1787–1985 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010), Death Place: New South Wales; Registration Place: Sydney, New South Wales; Volume Number: V18235798 2B

[32] 'Criminal Court,' Sydney Monitor, Saturday 29 November 1828, 1; 'Supreme Criminal Court,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Monday 1 December 1828, 2; 'Criminal Court,' The Australian, Tuesday 2 December 1828, 3; 'Postscript,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Monday 1 December 1828, 2

[33] William Bennett Jilks, full birth record transcript, Early Church Record Baptisms (NSW: NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages), Number: 372 V11, Volume Number: V18268128 1C; Australia Birth Index, 1788–1922 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010); Note, William Bennett Jilks was baptised on the 19 August 1827 by minister John Cross in the parish of Windsor.

[34] 'Supreme Court: Breach of Promise of Marriage: Miller V. Brett,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 21 June 1832, 3; 'Supreme Court: Civil Side,' Sydney Monitor, Saturday 23 June 1832, 2

[35] 'Geo Gilkes,' Date of Trial: 16 September 1814; England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791–1892 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009), Location of Trial: Middlesex, England; Crime: Larceny; Sentence: Transportation; 'George Gilkes, John Radley, Theft,' 14 September 1814, Proceedings of the Old Bailey, London's Central Criminal Court, 1674–1913, http://www.oldbaileyonline.org, viewed 15 August 2014

[36] 'Supreme Court: Breach of Promise of Marriage: Miller V. Brett,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 21 June 1832, 3

[37] Sydney Monitor, Saturday 23 June 1832, 2

[38] Maria Jilks née Jones, also a former convict. Maria had a life sentence but received a pardon.

[39] 'Supreme Court: Breach of Promise of Marriage: Miller V. Brett,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 21 June 1832, 3

[40] 'George Jilks,' Vessel: Mariner, New South Wales, Australia, Settler and Convict Lists, 1787–1834 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007).

[41] 1828 Census: Householders' Returns (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales) 65, Parramatta Series NRS 1273, Reel 2507

[42] Elizabeth A Bennett, Australia Birth Index, 1788–1922 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010), Volume Number: V182996 13; William H. Bennett, Australia Birth Index, 1788–1922 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010), Volume Number: V183161 15; 'An Old Parramatta Native,' Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 31 March 1906, 8

[43] 'Supreme Court: Breach of Promise of Marriage: Miller V. Brett,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 21 June 1832, 3; 'Breach of Promise of Marriage: Supreme Court,' The Australian, Friday 22 June 1832, 3; 'Supreme Court: Civil Side,' Sydney Monitor, Saturday 23 June 1832, 2

[44] In her choice of colonial mate, Elizabeth appears to have fared much better than her old friend Jane Wilson, who married a convict with a life sentence named William Quinland (arrived per Tyne). Quinland was employed to 'split posts' while Jane was either employed to work at the Parramatta Female Factory or was incarcerated there as she appears as a resident of the Factory in the 1828 census. The census also reveals Jane had begun to use an alias: 'Charlotte Quinland.' With this alias, Jane attempted to marry a second man while still married to Quinland, but after seeking permission from the Governor to marry, she was denied on the basis that there was no record of a 'Charlotte Quinland' on the Lord Wellington's list of convict passengers; see 1828 Census: Householders' Returns (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), Series NRS 1273 Reel 2552

[45] According to the 1828 Census, Charles Stephens was then 18 years old and had been transported with a 7-year sentence on the convict ship Prince Regent in 1827 while John Davis was 28 years old with a 14-year sentence and came to Australia per Florentia in 1828; 1828 Census: Householders' Returns (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), Series NRS 1273 Reel 2552

[46] fickle swain: a capricious admirer or suitor, willing to trifle with a young woman's affections

[47] 'Married,' Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 4 March 1847, 3

[48] 'Died,' Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 20 October, 1847, 3; 'Died,' The Australian, 22 October 1847, 3; 'Deaths,' Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, Saturday 23 October 1847, 3

[49] Buried in Section 2, Row F of St John's Cemetery, Parramatta. Judith Dunn, The Parramatta Cemeteries: St. John's (Parramatta: Parramatta and District Historical Society, 1991), 109; Michael Brookhouse, Photograph of Bennett and Bennett's sandstone altar with inscription, Australian Cemeteries Index, http://austcemindex.com/inscription.php?id=8629750, viewed 18 August 2014