The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Pyrmont

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Pyrmont

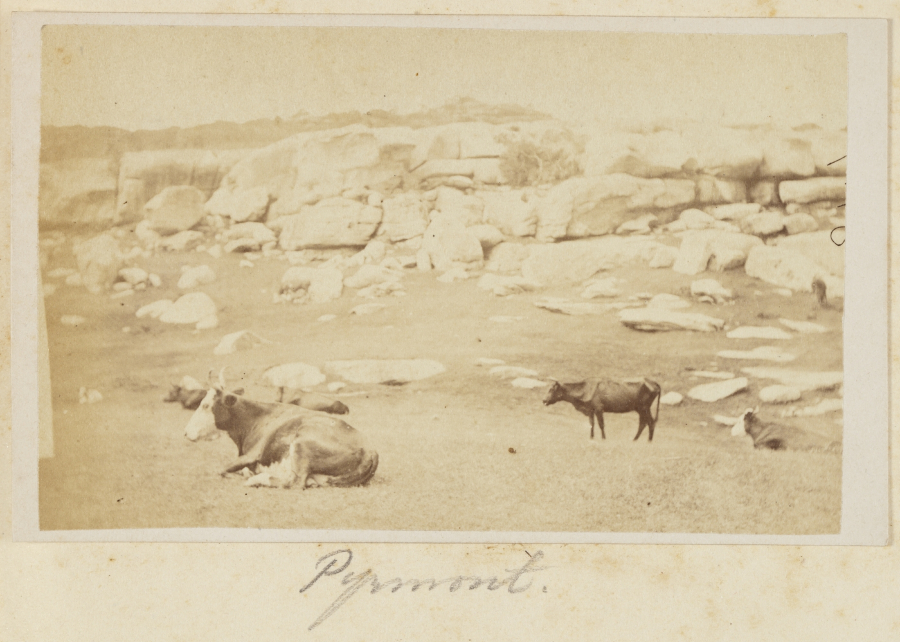

[media]Despite its proximity to the original settlement of Sydney, the development of Pyrmont was slow until the 1840s. Early artists sometimes portrayed Pyrmont as an isolated place, shrouded in mist, in the background of the city, a place where Aboriginal people gathered to keep watch over the strange ways of the new arrivals who were beginning to inhabit the area. Indeed, early European settlers recalled a distinct Aboriginal presence up to the 1830s.

Recent scholarly work suggests that the people living around Go-mo-ra (Darling Harbour) and the headwaters of the Blackwattle Creek may have formed a separate clan from the generally recognised Gadigal. Tentatively named the Gommerigal, this clan has yet to be officially recognised, but as late as 1830, Absalom West recorded the existence of a Darling Harbour 'tribe'. [1]

Europeans visiting Pyrmont in the early years were likely to do so by boat. It was famously visited by Captain John Macarthur and his entourage in December 1806, when the presence of a spring of natural water at the chosen picnic spot inspired the naming of the place 'Pyrmont', after a spa town of that name in northern Germany. The spring later became known as Tinker's Well.

Sandstone and industry

But it was the rock, rather than the spring that came to define Pyrmont and eventually the word Pyrmont became a byword for some of the best sandstone in the world.

For the first half century of European occupation, minimal industrial uses did little to alter the timeless landscape of Pyrmont. Macarthur built a windmill that ground grain for a few years, but it could not compete with the mills in the centre of the city, and it soon slipped into folklore as 'haunted'. After the land was finally subdivided in 1839, some shipbuilding and an iron works took tenuous hold of the shoreline, and a smattering of rough-hewn stone cottages appeared. But there was no [media]stampede to populate Pyrmont, and never a time when its residents did not share the space with industry and quarries.

In the [media]late 1840s, Darling Island was levelled and joined to the mainland with the hewn rock. The 'island' became home to the shipbuilding yards of the Australian Steam Navigation Company. By 1855 a patent slip was in use, repairing ships of up to 2,000 tons. Nearby, associated industries began to congregate.

[media]From the 1840s until the end of the nineteenth century, quarrymen hewed down the isolated western half of the peninsula for sandstone. Uncounted tons of Pyrmont 'yellowblock', as it was known, were carted into the city to build the great public buildings which remain the signature of Sydney's nineteenth-century built form. The quarries were known locally as 'Paradise', 'Purgatory' and 'Hellhole', in recognition of the difficulty of working the stone.

After the opening of the Glebe Island abattoirs in 1860, dusty streets were host to herds of cattle being driven to slaughter. When the killing was on, the sound of their bellows filled the air, and the waters of the harbour ran blood red. At the end of the day, hard men drank to ease the stress of it all at the Quarrymen's Arms, the Butchers' Arms, The Greentree, or at Kennedy's.

Eventually much of the trade of the colony passed through the wharves that lined the peninsula – the wheat and timber and coal that came in on the coastal ships, and went out again to make bread, construct buildings and heat the houses of the city and beyond.

At the northern end of the peninsula, the Colonial Sugar Refinery took in raw material from the Pacific, and turned it into sugar, rum, chemicals and building materials. For many decades, the company's Clydesdale horses hauled its products through the local streets and out to the rest of Sydney. A jumble of foundries, workshops and factories, with their attendant smells, smoke, dust and noise, were distributed across the landscape, with lorries and timber jinkers hauling heavy loads through residential streets.

Local residents give way to industry

By the end of the nineteenth century the population had peaked. Then it began to decline, as the land was taken up for expanding industrial activities. A great powerhouse smokestack signalled the arrival of the new power of electricity, which lit up the land but covered Pyrmont in a fine coating of coal dust. Even the much-loved harbour pool gave way to maritime industrial expansion, leaving only memories of a lost sandy beach, of catching yabbies and fish, a place of local romance and of fearless swimming competitions which the locals always recalled winning. Though the working rhythms of the wharves were relentless, the people of Pyrmont were also deeply committed to their sporting teams, especially their swimming, sailing and sculling clubs.

Industry abandons Pyrmont

Then these same industries began to disappear and people drifted away. For those who could afford it, the newer leafier suburbs beckoned, while others who remained watched their schools close and their amenities shrink. They read in the newspapers that the place they lived in was only a slum, ripe for bulldozing. Indeed, for the rest of Sydney, Pyrmont was a 'nowhere' place, somewhere to drive through to get to somewhere else, a bottleneck between the city and the suburbs. Eventually huge freeways were built that sliced through the centre of the peninsula, cutting Pyrmont off from neighbouring Ultimo.

By the 1980s, the area was full of derelict sites, abandoned workplaces and a small population of old-timers who were in shock over the brutal manner in which the fabric of the place was being torn down. They were grieving for the loss of meaning in their lives, and sceptical of the assurances of planners and developers who foretold a shiny, bright new future.

Pyrmont's reinvention and legacy

Today the peninsula has been more or less reinvented as a pleasant place of residences and high-tech industries. The feet that walk the pavements are more likely to wear shiny fashionable shoes than work-boots, and none of the children could imagine a time when others went barefoot to school. The stench of the sugar company boiling molasses has long gone. The dirt of the coal-fired powerhouse is but a distant memory, replaced by a glittering casino. Mean narrow terraces that housed large families have disappeared, along with the backyard chooks and the billycarts. The women who once worked over hot stoves creating a family tea from meagre ingredients are just as likely to say 'let's eat out tonight'. Chic dining and upmarket shops are dotted across a landscape once the home of cheap cafes, rough pubs and shops that stocked the most basic of everyday requirements.

It is a different place. And yet it is not. Just scratch the surface and the marks of past ways remain. Tarted-up wharves still echo past labours and art installations utilising bits of industrial machinery whisper of past work. The evidence of old quarries is all around, and the sandstone that underpins it all will always define the peninsula, and indeed, many other sites of the city. That sandstone, embedded in the Sydney psyche, means that many other places too are Pyrmont. The Sydney Town Hall in George Street, the fine old public buildings in Bridge and Macquarie streets, the great sandstone University of Sydney, respectable banks and formidable school facades – all of them are Pyrmont.

It is possible to live in Sydney and never visit the peninsula, but historically it has not been possible to live in Sydney without the labours of the people who lived and worked in Pyrmont.

References

Shirley Fitzgerald and Hilary Golder, Pyrmont and Ultimo Under Siege, Hale & Iremonger, 1994

Gary Deirmendjian, Sydney Sandstone, Craftsman House, Sydney, 2002

Michael R Matthews, Pyrmont and Ultimo A history, the author, Sydney, 1982

Notes

[1] Keith Vincent Smith, 'Eora Clans: A History of Indigenous Social Organisation in Coastal Sydney, 1770–1890', MA thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, 2004, pp 70–72

.