The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Robert ‘Nosey Bob’ Howard

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Robert Rice Howard

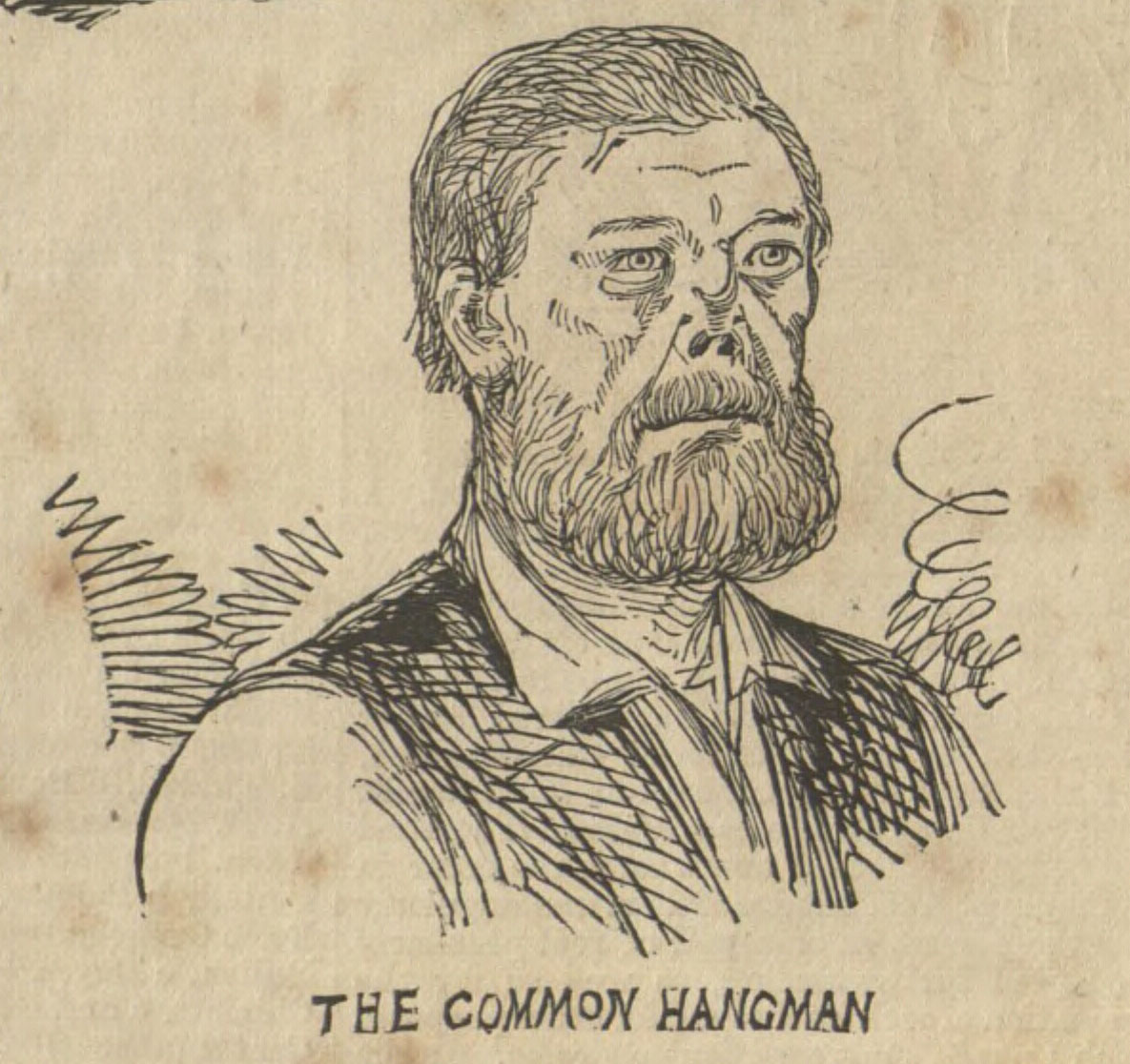

[media]Robert Rice Howard was a successful Sydney cab driver in the mid-nineteenth century. When he lost his nose in an accident, the disfigured cabbie also lost much of his business, and the man who came to be known as ‘Nosey Bob’ took on the role of hangman for New South Wales.

Marriage and children

Robert Rice Howard was born in early 1832 in Norfolk, England, to Henry Howard and Mary Ann Howard, née Rice.[1] In 1858, the 26-year-old Howard, who was working as a coachman like his father, married Jane Townsend, the daughter of a stonemason, at Saint Luke’s Church in Charlton, now a suburb in south east London.[2] Robert and Jane Howard welcomed their first three children in England: Mary Ann, Emily Jane and Edward Charles.[3] In the 1860s the Howards decided to emigrate to Australia, arriving in Moreton Bay in early 1866.[4] After the birth of Fanny, in Brisbane, the growing family moved again, leaving Queensland for New South Wales where they were soon joined by sons Sydney and William George.[5]

A successful career, ruined by an accident

Howard was apparently a tall and good-looking man, who ‘passed for an Adonis amongst the horsey crowd’[6] and was allegedly the preferred coachman for Government House.[7] Some newspaper articles even claimed Howard was called upon to drive for His Royal Highness, Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, during his visits to Sydney, but this has never been substantiated.[8]

Almost every published account of Howard’s life includes a statement that he lost his nose when he suffered a horse’s kick to the head, with his terrible disfigurement instant and irreparable. There are several different versions of this story, but there are no specifics offered. Even when Howard recounts his own transition from cab driver to executioner, there are few details:

I used to drive a cab. I was always amongst horses from a boy, but although I had a good turn-out and was always well dressed, I found that the public, ladies particularly, objected to engage me owing to this disfigurement, which I had suffered through an accident with a horse. The post of assistant-executioner became vacant and I applied for it and got it. I had no idea then of becoming the principal, but that fell to me in due course.[9]

With a wife and six children to support, a disfigured and desperate Howard may have felt he had few options. A permanent position with the colony’s Department of Justice may have brought with it the infamy of being the executioner, but it also offered financial security for himself and his family.

Howard’s debut as a hangman

Some histories start Howard's career as a hangman in 1875[10] yet when George Pitt was executed on 21 June 1876 in Mudgee, the state's principal hangman, William Tucker (or Tuckett), was followed out by his new assistant. Reports noted that Tucker’s offsider, presumably Howard, ‘was recognised as having once been in good circumstances in Sydney’.[11] Just days later Michael Connolly was hanged on 28 June 1876 in Tamworth.[12] When Daniel Boon was hanged on 19 July 1876 in Wagga Wagga, the assistant executioner was mentioned in newspaper reports as a man ‘whose naturally repulsive appearance was heightened by the absence of any nose’.[13] Thomas Newman was the next man executed in New South Wales, mounting the scaffold in Dubbo ‘with a hangman on either side’, on 29 May 1877.[14]

When Peter Murdick was hanged in Wagga Wagga on 18 December 1877, there was no mention of an assistant accompanying the senior hangman who arrived from Sydney. This senior man was very likely to have been Robert Howard.[15] Only one person was hanged in New South Wales the following year, In Chee on 28 May 1878 in Goulburn.[16] When Alfred, an Aboriginal man, was hanged on 10 June 1879 in Mudgee, it was clear that Howard held the position of senior executioner for the colony of New South Wales.[17]

Such was the stigma attached to the role of hangman however, that his employment was not published in the NSW Government Gazette until 1896 and the Public Service List until 1897, creating some confusion around the dates of his first work on a scaffold.[18] When Howard was first publicly listed as a civil servant, he had actually been the principal hangman for around two decades.

A happy family, but a horrible job

Howard once told JF Archibald, co-founder of The Bulletin, that he took the job and was ‘not ashamed of it’. He explained that he was a comfortable man who could support his children – they were all clean, well read and well mannered – and that he had ‘as good a garden as there is anywhere’.[19] Despite a happy home life, the task of the executioner took a toll.

Howard, like many of his predecessors in the role, was known to drink, though he never appeared drunk on the job. His drinking was reported as early as the late 1870s and by the mid-1880s his problems with alcohol were widely acknowledged. It had ‘to be admitted, Robert usually gives way to drink, and may often then be seen, clad in the strictest black, helplessly clasping a lamp-post’.[20]

Howard was at this time battling public revulsion and private loneliness. His wife of almost 20 years died at home aged 42 on 22 August 1878. It was suggested that Jane died of shame, that being married to a hangman who was constantly insulted and taunted was more than she could bear.[21] Her death certificate states the cause of death less fancifully as ‘Disease of Lungs (4 months)’ and ‘Pleuritic Effusion’.[22]

It has also been suggested that his ‘three beautiful daughters were condemned to lives of lonely spinsterhood because, as the story goes, no suitor was willing to suffer the ignominy of having a hangman as father-in-law’.[23] Yet, Mary Ann married Edward Hawkins, at a registry office on 20 May 1879 and Fanny married Harry Bullenthorpe at St Peter’s Anglican Church in Darlinghurst on 4 April 1885.[24] Emily Jane died from heart disease, on 20 December 1880, when she was just 18 years old.[25] At least two of Howard’s three sons also married.[26]

Bad bungles and famous felons

Nosey Bob, during his tenure as an executioner, witnessed some scientific developments designed to improve the process of hanging. An official ‘Table of Drops’ was created in 1888 and updated in 1892. These tables, an improvement on the standard long drop of 8 feet that had been determined in 1880, took some of the guesswork out of hanging by listing how far a felon had to fall, based on their weight in pounds, to facilitate a dislocated neck as swiftly and cleanly as possible.[27] Basically, the heavier the criminal, the shorter the drop. Unfortunately mistakes were still made. At one extreme, the condemned could be strangled. When Henry Tester was hanged on 7 December 1882 in Deniliquin, it was thirty-five minutes after the bolt was drawn before he was declared dead.[28] At the other extreme, prisoners could lose their heads. When William Liddiard was hanged on 8 June 1886 in Grafton, it was declared that ‘death must have been instantaneous, for the head was almost severed from the body by the rope’.[29] When Howard set ropes for Charles Montgomery and Thomas Williams on 31 May 1894 in Darlinghurst Gaol, Montgomery’s death was instant, but Williams suffocated[30] after the men were put before ‘the wrong ropes, Montgomery being the tallest man was given a drop of 10 feet and Williams only 8 feet’.[31]

Howard claimed that he ‘had very few bungles’[32] but the newspapers disagreed, and ‘Nosey Bob’, as the press labelled him, was the subject of dozens of damning articles. When he botched the hangings of Montgomery and Williams, newspaper headlines such as ‘Our Hangman’s Horrible Blunder’, ‘A Horrible Bungle’, ‘Horrible Bungle on the Scaffold’ and ‘Another Bungle’ appeared across the country.[33]

Howard hanged felons across New South Wales, but almost half of his work was completed at the imposing Darlinghurst Gaol where he hanged some of the most famous criminals of colonial Sydney. When 11 men were tried for the rape of Mary Jane Hicks in 1886, nine were found guilty. Five had their sentences commuted but four – George Duffy, Joseph Martin, William Boyce and Robert Read – met Nosey Bob on 7 January 1887.[34] Howard also hanged Louisa Collins, accused murderer and the last woman executed in New South Wales, on 8 January 1889, and notorious baby farmer John Makin on 15 August 1893.[35] He also 'turned off' Frank Butler, Australia’s first serial killer, on 16 July 1897, as well as the last bushrangers of New South Wales, Jacky Underwood at Dubbo on 14 January 1901, and Jimmy Governor at Darlinghurst on 18 January 1901.[36]

Retirement and death

Nosey Bob’s last job was a double hanging, Digby Grand and Henry Jones, who were convicted of murder, on 7 July 1903 in Darlinghurst Gaol (Grand was slowly strangled, Jones had his neck dislocated).[37] Then, after 28 years of continuous service, Howard finally retired in May 1904. He was on the same annual salary of £156 (roughly equivalent to $150,000 in 2019) that he had been on in 1876.[38]

Though his profession was reviled, many thought of Howard ‘as a quiet, inoffensive man, who is ever ready to give his mite towards the assistance of any case of distress or to do a good deed for any of his fellow creatures’.[39] It was, however, noted upon his retirement that ‘Robert Howard’s 'work' of late years has been fairly well performed, but at times there was a recklessness about it which caused extreme pain to the public and the hanged’.[40]

After his retirement Howard continued to live in his modest timber cottage at north Bondi on Brighton Boulevard, just off modern-day Campbell Parade, where he had moved in the 1880s.[41] He still liked a drink, and he famously trained a horse to carry a billy and make the return trip from his home to a local establishment. The billy carried a sixpence there and beer on the way back.[42] His short retirement was quiet. He spent time with his family, he looked after his animals and he tended his garden. Howard also spent time fishing, having developed a reputation for being very good at catching sharks.[43]

Robert Rice Howard died of endocarditis and senile decay on 3 February 1906 at the age of 74, less than two years after retiring.[44] All of his surviving children received blocks of land on his death.[45]

A popular character

Nosey Bob remained a firm feature of popular culture in New South Wales long after his passing. Like the famous English hangmen ‘Bull’ and ‘Jack Ketch’, ‘Nosey Bob’ became a byword for an executioner in Australian cultural references for many years.

Shortly before Howard died, one author quipped: ‘I’m that thirsty I’d drink with Nosey Bob’, a phrase that became an Australian colloquialism.[46] When it was rumoured that the judge William Charles Windeyer – a man who generated quite a bit of business for the executioner during his career – was writing a book of poetry, it was suggested that the volume should 'open with an apostrophe to the gallows, and to conclude with a sonnet to 'Nosey Bob', the N.S.W. hangman’.[47]

References

Beck, D, Hope in Hell: A History of the Darlinghurst Gaol and National Art School, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2005.

Family History, Sydney: Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages NSW, various years.

Haughton, S, ‘On hanging considered from a mechanical and physiological point of view’, London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, Vol.32, No.213, 1866, pp.23–34.

‘Howard, Robert [vertical file]: “Nosey Bob” the Hangman’, Waverley Library Local Studies Collection, Waverley, 1832–1902, call no. VF HOWA.

Public Service List, Sydney: New South Wales Government Printing Office, 1897 and 1903.

Report of the Committee Appointed to Inquire into the Existing Practice as to carrying out Sentences of Death [Aberdare Report], London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1888.

The Earl of Kimberley, Secretary of State for the Colonies (Downing Street, London), Circulars on Capital Punishment, Queensland State Archives, Brisbane, 27 June–28 December 1880, call no. ITM17282.

Sydney, Suburban and Country Commercial Directory, Sydney: John Sands Ltd, various years.

Ward, Ross, The Office of the Sheriff: A Millennium of Tradition, Sydney: Department of Courts Administration, 1992.

Notes

[1] The Parish Register of Holy Trinity Church in the County of Norfolk lists Robert Howard’s baptism as 14 March 1832, Line No. 525. The same register, 16 pages later with baptisms for 1837, lists Howard’s baptism again. In the second entry, the baptism takes place two days earlier on 12 March 1832. An asterisk points readers to a note at the base of the page: ‘This child was privately baptized during my absence, and the Parents, neglected to give notice or to see it registered at the time. Arthur Browne, Vicar of Marham. Witness Mary Anne Howard, the mother of the child, her X mark’, Line No. 653.

[2] 'Robert Rice Howard and Jane Townsend: Certified copy of an entry of marriage’, General Register Office, England and Wales, 26 October 1858, Ref. No. MHX 826435.

[3] 'Mary Ann Howard: Baptism’, Parish Register of Christ Church Bermondsey in the County of Surrey, 19 February 1860 [date of birth, 19 November 1859, listed in margin], Line No. 203; ‘Emily Jane Howard: Birth’, Superintendent Registrar’s District Tetbury, Counties of Gloucester and Wells, 20 May 1862, Line No. 282; ‘Edward Charles Howard: Birth’, Superintendent Registrar’s District Hendon, County of Middlesex, 29 November 1864, Line No. 451.

[4] Robert and Jane Howard – with children Mary Ann, Emily Jane and Edward Charles – arrived in Moreton Bay on 27 February 1866 on the Legion of Honour. All Queensland, Australia, Passenger Lists, 1848–1912.

[5] ‘Fanny Howard: Birth’, Register of Births in the District of Brisbane, Brisbane, 13 June 1867, Line No. 7155; ‘Sydney Howard: Birth’, New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, Sydney, 5 November 1869, Reg. No. 16207/1869; ‘William George Howard: Birth’, New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, Sydney, 30 June 1872, Reg. No. 1660/1872. The Howards had another baby with one ‘male deceased’ listed on the birth registrations of the three children they had in Australia. It is not clear when this baby was born or what happened to him.

[6] Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative, 25 February 1915, p6 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156867175 viewed 25 October 2020.

[7] Truth (Brisbane), 20 January 1901, p5 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article200509793 viewed 6 December 2020.

[8] An article in Truth (Sydney), 27 June 1897, p1 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article169748152, viewed 6 December 2020, is one of the earliest accounts of Howard’s rumoured royal connections. Several more articles connecting Robert Howard to the Duke of Edinburgh appear in the Truth from the late 1890s, with similar stories appearing in newspapers well into the 20th century, including Kiama Reporter and Illawarra Journal, 23 February 1901, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article102777549, viewed 2 January 2021; Freeman’s Journal, 17 February 1906, p.16 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article119939668, viewed 3 January 2021; Voice, 2 May 1936, p1 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article219395063, viewed 2 January 2021.

[9] Sunday Times, 12 January 1896, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article130406278 viewed 25 October 2020.

[10] Several accounts of Robert Howard's career suggest that he first assisted with the hanging of Johnny McGrath on 14 September 1875 at Darlinghurst Gaol, with at least one report stating that the unfortunately named George Rope, hanged on 7 December 1875 in Mudgee, was Howard’s first effort as an executioner. Truth (Sydney), 3 October 1897, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article169751632 viewed 6 December 2020; Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative, 25 February 1915, p6 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156867175 viewed 25 October 2020.

[11] Australian Town and Country Journal, 24 June 1876, p9 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article70592485 viewed 20 September 2020.

[12] Herald, 8 July 1876, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article244274936 viewed 30 December 2020.

[13] Burrangong Argus, 26 July 1876, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article247274021 viewed 20 October 2020.

[14] Glen Innes Examiner and General Advertiser, 13 June 1877, p5 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217809203 viewed 30 December 2020.

[15] Australian Town and Country Journal, 22 December 1877, p40, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article70611590, viewed 6 December 2020.

[16] Queanbeyan Age, 1 June 1878, p1 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article30673461 viewed 30 December 2020.

[17] Evening News, 10 June 1879, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article107148311 viewed 30 December 2020.

[18] NSW Government Gazette, 17 June 1896, p4182; Public Service List, Sydney: New South Wales Government Printing Office, 1897, p80.

[19] Bulletin, 31 January 1880, pp4–6.

[20] Daily Telegraph, 8 July 1879, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article239284269 viewed 3 October 2020; North Australian, 18 July 1884, p5 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article47992256 viewed 29 October 2020.

[21] ‘Robert “Nosey Bob” Howard (1832–1906)’, Waverley Library, Sydney, 2009, p2.

[22] ‘Jane Howard: Death’, New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, Sydney, 22 August 1878, Reg. No. 3220/1878.

[23] ‘Robert “Nosey Bob” Howard (1832–1906)’, Waverley Library, Sydney, 2009, p2.

[24] ‘Edward Hawkins and Mary Ann Howard: Marriage’, New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, Sydney, 20 May 1879, Reg. No. 1847/1879; ‘Harry Bullenthorpe and Fanny Howard: Marriage’, Parish Register of the Church of Saint Peter in the County of Cumberland, 4 April 1885, Line No. 570.

[25] ‘Emily Jane Howard: Death’, New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, Sydney, 20 December 1880, Reg. No. 3998/1880.

[26] ‘Edward Charles Howard and Mary Stevens: Marriage’, Parish Register of Church of Saint Matthias in the County of Cumberland, 20 September 1893, Line No. 20; ‘Sidney Howard and Elizabeth Donohue: Marriage’, NSW Births, Deaths and Marriages, Sydney, 3 February 1896, Reg. No. 332/1896.

[27] The origin of the long drop is unclear. Samuel Haughton, an Irish scholar, promoted the long drop in 1866 and William Marwood, an English hangman, used the long drop from 1874. A drop of around 8 feet was formally recommended in 1880. A ‘Table of Drops’ was then developed, but this changed over the years. The first official version of the ‘Table of Drops’ came out with the Aberdare Report in 1888. James Berry, another English hangman, also worked on tailoring drops, though his table is harder to follow as drops are given in feet only; the other tables noted here offer drops in feet and inches. In 1892, the ‘Table of Drops’ was updated, with drops to be ‘calculated by dividing 840 foot pounds by the weight of the culprit and his clothing in pounds, which will give the length for the drop in feet’. In a reflection of older practices, it was specified that ‘no drop should exceed 8 feet’. The table insisted that criminals 105 pounds and under should fall 8 feet, while those weighing 210 pounds should fall just 4 feet. Samuel Haughton, ‘On hanging considered from a mechanical and physiological point of view’, London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, Vol.32, No.213, 1866, pp.23–34; James Berry, My Experiences as an Executioner, edited by H Snowden Ward, Percy Lund & Co, London, 1892; The Earl of Kimberley, Secretary of State for the Colonies (Downing Street, London), Circulars on Capital Punishment, Queensland State Archives, Brisbane, 27 June–28 December 1880, call no. ITM17282; Report of the Committee Appointed to Inquire into the Existing Practice as to carrying out Sentences of Death [Aberdare Report], London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1888; ‘Executions – Table of Drops (April, 1892)’, reproduced in Ross Ward, The Office of the Sheriff: A Millennium of Tradition, Sydney: Department of Courts Administration, 1992.

[28] Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser, 15 December 1882, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article192857334 viewed 19 October 2020.

[29] Northern Star, 16 June 1886, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71719386 viewed 7 November 2020.

[30] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 June 1894, p5 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13953641 viewed 6 December 2020.

[31] Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, 31 May 1894, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article62962703 viewed 2 December 2020.

[32] Truth(Sydney), 8 January 1899, p8 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article168082557 viewed 29 December 2020.

[33] Bird O’Freedom, 2 June 1894, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article207806542 viewed 29 December 2020; Maryborough Chronicle, 1 June 1894, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article146978561 viewed 29 December 2020; Narracoorte Herald, 1 June 1894, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article147002098 viewed 29 December 2020; Age, 1 June 1894, p5 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197474629 viewed 29 December 2020.

[34] Kate Gleeson, ‘From Centenary to the Olympics, Gang Rape in Sydney’, Current Issues in Criminal Justice, Vol. 16 No. 2, 2004, pp183–201.

[35] Rachel Franks, ‘A Woman’s Place: Constructing Women within True Crime Narratives’, TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Courses, special issue 34, 2016, pp1–15; Weekly Times, 19 August 1893, p15 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article221782695 viewed 29 December 2020.

[36] Truth (Sydney), 8 January 1899, p8 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article168082557 viewed 29 December 2020; Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 26 January 1901, p202 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article165294990 viewed 29 December 2020.

[37] Australian Star, 7 July 1903, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article228620932 viewed 6 December 2020.

[38] Public Service List, Sydney: New South Wales Government Printing Office, 1897, p80; Public Service List, Sydney: New South Wales Government Printing Office, 1903, p64; Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of Australian Amounts, 1828 to the Present, MeasuringWorth.com website https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/australiacompare/ viewed 4 January 2021.

[39] Sunday Times, 12 January 1896, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article130406278 viewed 25 October 2020.

[40] Truth (Brisbane), 5 June 1904, p7 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article199303253 viewed 6 December 2020.

[41] ‘In this cottage at North Bondi, Sydney, lived Nosey Bob [caption on photograph]’, Melbourne: State Library of Victoria, ca.1914–ca.1941, call no: H22729.

[42] Table Talk, 20 August 1897, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article145930978 viewed 4 October 2020.

[43] Cobargo Chronicle, 20 January 1899, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106443138 viewed 29 December 2020.

[44] ‘Robert Howard: Death’, New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, Sydney, 3 February 1906, Reg. No. 3518/1906.

[45] Howard, Robert: Probate Packet, State Archives & Records NSW, Sydney, 1880–1939, Call No. NRS-13660-5-SC001531-Series 4_36697.

[46] Randolph Bedford, The Snare of Strength, London: William Heinemann, 1905, p294; GA Wilkes, A Dictionary of Australian Colloquialisms, Sydney: Sydney UP, in association with Oxford UP, 1990, p129.

[47] Truth (Sydney), 6 December 1896, p1 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article169755601 viewed 22 December 2020.