The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Royal Botanic Gardens

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Royal Botanic Gardens

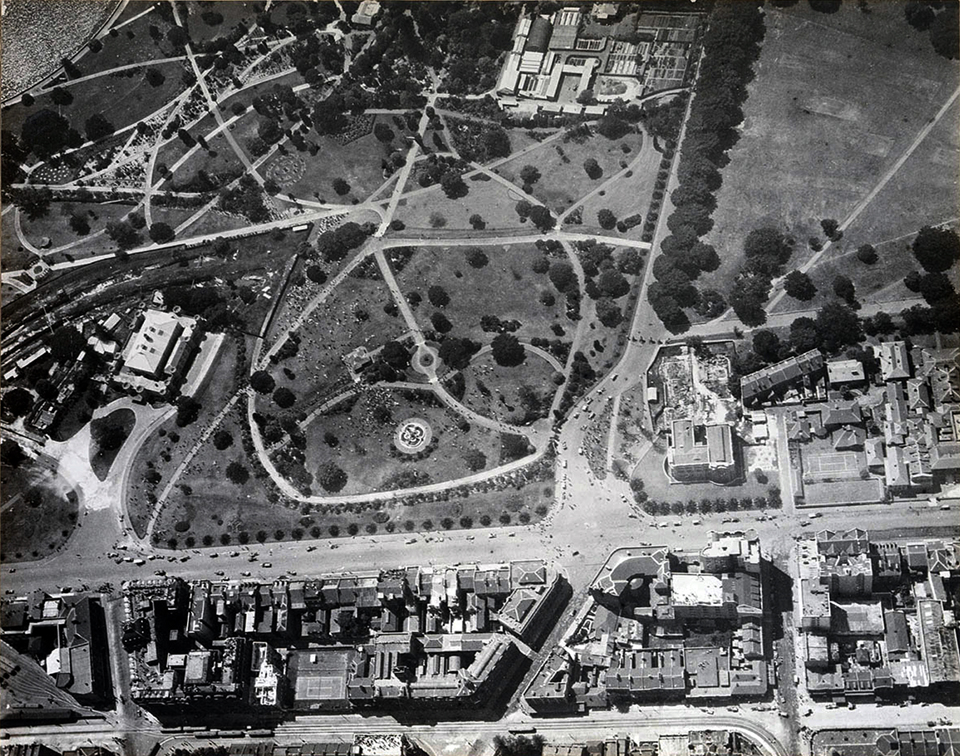

Sydney is [media]blessed with its spectacular Royal Botanic Gardens, situated on land originally set aside as the 'Governor's demesne', ensuring that such a public asset remains on the harbour shores in the heart of the ever-expanding city.

Even as early as the 1840s, visitors commented on the Garden's charm and visual impact: John Hood, from Berwickshire, arriving from the Far East, rhapsodised [media]about

the most beautiful spot I ever saw…the Botanical Gardens of Sydney. It was literally a walk through Paradise… [1]

[media]The gardens also reflect the changing styles of 'public gardens' – from the utilitarian beds that provided the necessities of life in the early years, to the emerging styles associated with new ideas about landscape gardening for visual effect, to the overwrought overkill of Victoriana, with statues, urns, terraces, ponds, plinths and obelisks at every turn, through to the contemporary acceptance of the validity of 'native' flora as a legitimate focus in a public garden.

From bush to garden

Over 200 years of white history, the area now known as the Royal Botanic Gardens has undergone various transformations. Originally, it would have been an area of native vegetation: plants and flowers and trees indigenous to the area – eucalypts, acacias, native fuchsias, cabbage tree palms, paper barks, swamp oaks, and Port Jackson figs among many other varieties. [media]However, with the encroachment of the First Fleeters, new needs arose, and old vegetation was cut down to be replaced by what the newcomers saw as the necessities for survival. [media]Thus the early years saw the development of 'kitchen garden' farmlets in the area, with plantings of everything from spinach, celery, parsley, carrots, potatoes, onions, beans and peas, to wheat, barley, rye and oats. But there was also nostalgia for 'home', which saw the planting of apple trees, English oaks, stone pines and other 'British' trees. Recently, the sites of some of the early kitchen gardens have been rediscovered, within the boundaries of today's Botanic Gardens.

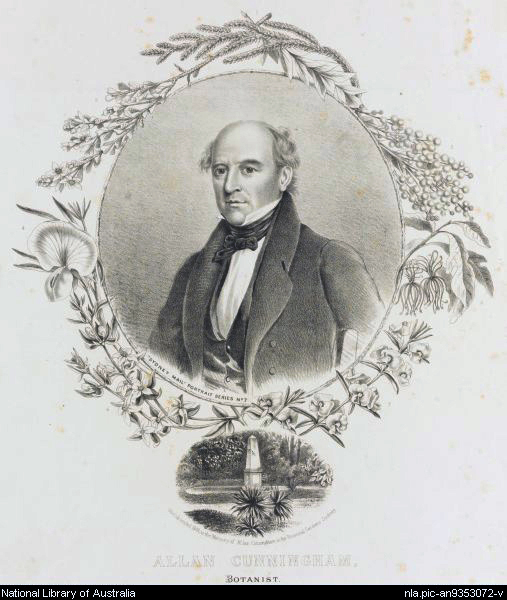

But the early settlers also brought with them a range of 'exotics' – such as coffee and cocoa seeds, sugar cane, quinces, rice and figs, among others – all collected from stop-over ports on their way to the new colony, and seen as useful additions to the basics for survival in a new land. Such was the perceived value of this endeavour that, by 1821, the duties of [media]the Colonial Botanist were principally

the culture of such Exotics as are from time to time introduced into the Garden from various parts of the Globe...the propagating of all Sorts of Fruits and Grasses that are interesting...And the forming of a General Collection and arrangement of Plants. [2]

That such a garden had a practical bent is also evident from the comments in 1823 of Commissioner Bigge, who commended the establishment of a 'botanic' garden in the convict colony, noting that

the value of such an establishment, both in affording means of collection and experiment, and more particularly of diffusing throughout the colony the most valuable specimens of foreign grasses, plants and trees, is unquestionable. [3]

In the same year that the term Jardin Botanique first appears, in a map of Sydney by the French explorer Louis de Freycinet. [4] These guiding principles have been influential ever since.

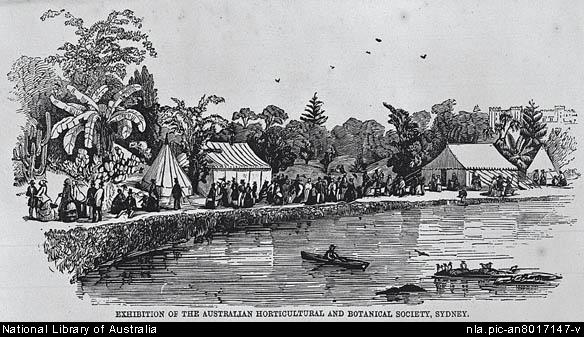

[media]The nineteenth century's world-wide exploration gave added impetus to the growing collection, and exotics from newly 'discovered' or explored areas were constant additions to the Gardens' collection.

[media]The Botanic Gardens were also the site of the ill-fated Garden Palace, a grandiose building that was designed by one of Sydney's most prominent architects, James Barnet. Opened in September 1879, it stretched from the site of today's State Library to the Government House stables (now the Sydney Conservatorium), but burned down in a spectacular fire in the early hours of 22 September 1882.

Victorian and modern gardens

[media]Because the bulk of the Gardens' landscaping – especially the lower Garden and Palace Garden – were laid out in the second half of the nineteenth century, the place retains a distinctive Victorian character even today, although new ideas – such as the so-called 'Parks and Gardens Movement' – have made an impact.

[media]In 1958 the Trustees of the Gardens recommended, in view of their long history and association with Royal visits since 1868, that the Gardens should be granted the Royal epithet, and this was done the following year.

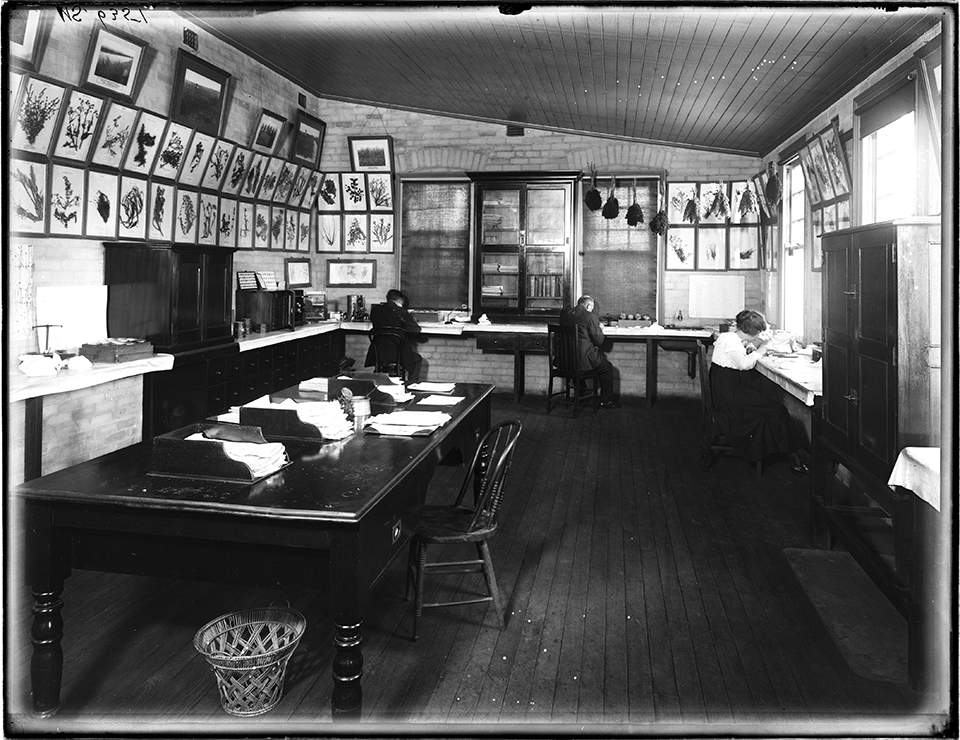

[media]But the Gardens are not merely a thing of beauty: they are also a centre for ongoing scientific research, with herbarium collections, library, and laboratories with electron microscopes and microcomputers. While some of its earlier features – like the Aviary and Zoo – have disappeared, some older features such as the Lion's Gate, the Museum and Lecture Hall have been joined by some important late twentieth-century additions, including the Rose Garden (1988), the Fernery (1993), the Herb Garden (1994), and the Oriental Garden (1997) and the Rare and Threatened Species Garden (1998).

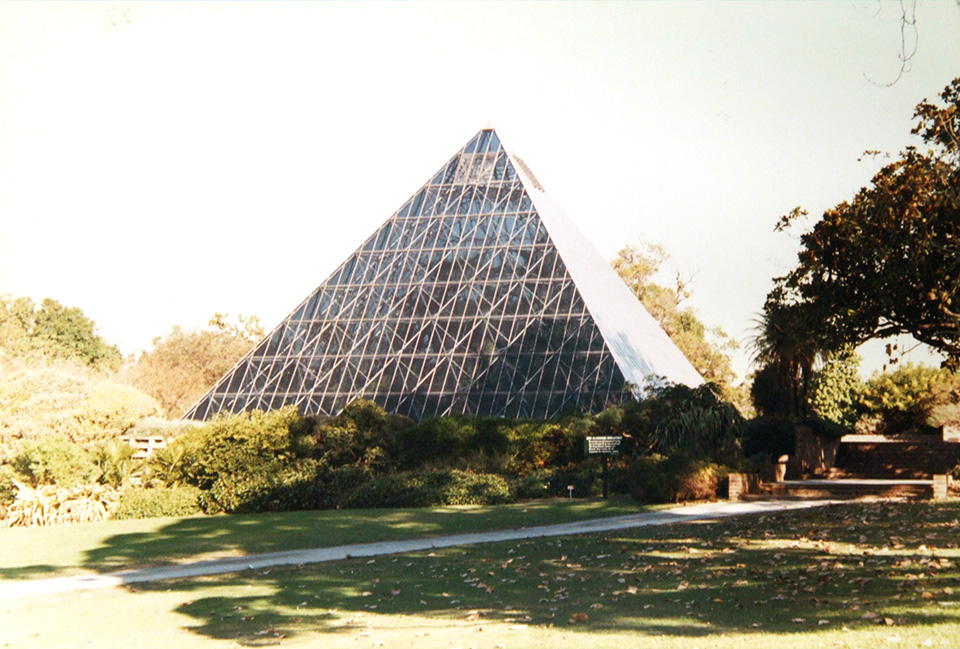

Probably the most visited areas of the Gardens today are the Arc Glasshouse (Tropical Centre), the [media]Pyramid, and the Wollemi pine: several of the species Wollemia nobilis, once thought to be extinct, were discovered in 1994 in sandstone gorges near Sydney, and one was replanted in the Gardens.

References

Edwin Wilson, Poetry of Place: Royal Botanic Gardens, Botanic Gardens Trust, Sydney, 2004

Lionel Gilbert, The Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney: A History 1816–1985, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1986

Margaret Hendry, 'The Profession of Landscape Architecture in Australia – Some Historical Influences on Theory and Practice', at Australian Institute of Landscape Architects website, http://www.aila.org.au/LApapers/papers/historyhendry/history-hendry.htm, viewed 18 February 2009

Notes

[1] John Hood, Australia and the East, John Murray, London, 1843, pp 103–4

[2] Returns of the Colony for 1822, Colonial Secretary's Office, Sydney, p 69

[3] J T Bigge to Earl Bathurst, Report of the Commissioner of inquiry on the state of agriculture and trade in the Colony of New South Wales, London, 1823, pp 93–4

[4] Peter Bridges, Foundations of Identity, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1995

.