The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Royleston

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Royleston

Royleston, [media]a Federation house at 270 Glebe Point Road, Glebe, served as a home for school-aged boys from 1922 until 1983. It has had many names, including Royleston Depot and Royleston Home, spelt variously Roylestone Home for Wayward and Abandoned Boys and Roylstone Home for Crippled Children. Some former residents remember the name as it sounded – 'Royalston'. [1] Like the nearby girls' institution, Bidura, it was a depot or receiving home for children waiting for hearings in the Metropolitan Children's Court or for children who were moving between foster care placements and institutions. Most school-aged boys who experienced the New South Wales Government child welfare system passed through Royleston at some point in their childhoods, including members of the Stolen Generations, but no one seeing the house today would appreciate its past.

The history of the house

Glebe Point Road is Cadigal and Wangal land which was granted to the Church of England in 1789 as the Sydney Glebe and subdivided in stages after 1828. [2] The land on which 270 Glebe Point Road stands was part of the Allen Subdivision of the Toxteth Estate. The house appears to have been built in 1896 or 1897 and Sands Directory of 1897 shows that a solicitor called William TA Shorter was the first known resident and that it was then called 'Wahroonga'. [3]

In 1898 Colonel JB Taunton was living in the house and complained to the Council that there was a Chinese joss house directly behind it: [4]

…from midnight, omnibuses and cabs arrived continuously, bearing crowds of noisy Chinamen; and how, from 2 o'clock in the morning till daylight, irrepressible and presumably devout celestials kept their Christian friends awake by means of 'tom-toms, whistles, firework fusillades, and other discordant sounds,' sleep being quite out of the question.

In 1903 Wahroonga, then numbered 234 Glebe Point Road, changed hands and was occupied by Carl Carlson. [5] The following year the house was renamed 'Carlson House' but Carlson died that August. [6] The house was then occupied by Carlson's widow and Mr and Mrs JA Kerr, her son-in-law and daughter. Around 1910 the street was renumbered and the address became 270 Glebe Point Road. [7] In 1920 it seems the Kerrs were using the name 'Wahroonga' again. [8]

It is difficult to pinpoint when Royleston began operating as a Child Welfare Department home. According to the State Records Authority of New South Wales:

Although stated [by the Child Welfare Department] to have been first occupied on 13 May 1924, with conveyance to the Crown completed on 11 July 1925, Royleston is listed as having 19 residents, with 4 admissions and 3 discharges, on 5 April 1922. On 31 December 1923 there had been 229 admissions and 203 discharges, with 20 currently resident, and on 31 December 1924, there had been 392 admissions and 396 discharges, with 46 remaining in residence. [9]

Sands Directory lists Bidura as 'Depot for State Children' in 1923, and the Kerrs as residents at 270 Glebe Point Road, so it is likely that Royleston began operating in another property. [10] That explanation might also solve the riddle of why the house became known as Royleston.

Royleston at 270 Glebe Point Road was officially gazetted as a children's home in 1924 by which time the Child Welfare Act had been passed, placing the home under the management of the new Child Welfare Department. [11] Sands Directory first lists it as Royleston Home – Child Welfare Department, in 1925. [12] A married man and woman were appointed officers in charge. [13]

The role of Royleston in the child welfare system

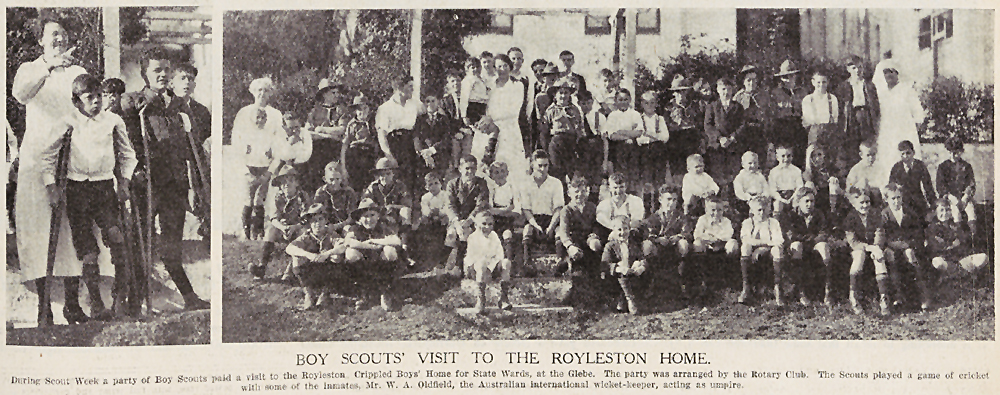

[media]Royleston was intended to ease pressure on the accommodation at the depot at Bidura and in the Metropolitan Boys' Shelter, which was a remand home attached to the Metropolitan Children's Court in Albion Street. [14] Royleston was for school-aged boys, most of whom were sent there because they had been 'charged' with neglect, rather than offences. Some newspapers of the 1920s and 1930s describe Royleston as a home for 'crippled boys' but this was possibly intended to stir the tender hearts of readers who might then offer donations. [15] The Child Welfare Department always referred to Royleston as a depot and it served the same functions as Bidura by providing temporary accommodation for children in transit between children's court hearings, foster care and institutions. [16]

Like Bidura, Royleston has strong associations with the Stolen Generations. In the early twentieth century New South Wales had a separate child welfare system for Aboriginal children run by the Aborigines Protection Board (later known as the Aborigines Welfare Board). However, the Child Welfare Department and the Protection Board worked together to remove Aboriginal children from their families by prosecuting them for neglect in children's court hearings. [17] Royleston was the main depot for children who were waiting for prosecution and was the transit point for their referral to institutions like Mittagong Farm Homes or the Protection Board's Kinchela Boys' Home. As a result, Royleston was the place many members of the Stolen Generations entered 'care'.

'Care' in Royleston

For many wards, Royleston was their first experience of the state welfare system and past residents have reported that the regimentation and dormitory-style accommodation came as quite a shock, as did being separated from their sisters, who were sent to Bidura. Christine Kenneally, writing in The Monthly in 2012, reported the memories of Geoff Meyer, who was taken into care as an infant in 1937:

Meyer stayed at Bidura until he was four, when he was sent to the Royleston Boys' Depot…the Royleston mansion is a Victorian hybrid of grand and delicate, featuring a graceful verandah and soaring windows. When the heavy iron gate first opened for Meyer, he was terrified by its squeal. Royleston housed 30 to 50 boys at a time until they were fostered, though many were repeatedly fostered, returned, and fostered again. Meyer never learned any other boys' names. "We weren't allowed to talk to each other," he said, "and the staff always said 'Hey you' or used terrible words." [18]

Like most Child Welfare Department institutions opened at this time, Royleston was chosen for its large rooms, including a ballroom and gardens, which enabled the accommodation of large numbers of children. In 1936, after Glebe residents complained about state wards from Bidura and Royleston attending local schools, a school was established on the premises with a resident teacher and a visiting manual training teacher. [19]

As the 2004 Senate Inquiry into Forgotten Australians noted, the Child Welfare Department always talked Royleston up, saying it provided very comfortable, temporary accommodation for boys in an attractive old house with many interesting features. [20] Yet boys who experienced it remembered it differently:

Royleston was a terrible place to find yourself, at any age. As a child, under care at Royleston, I felt the heavy hand of adult men, men employed to care for us. When they weren't happy, we suffered. Over time this treatment developed your sense of hopelessness, worthlessness, and aloneness. At times even the good guys had a heavy hand.

Each time you entered, you were reduced to a manageable unit, private property was removed and never seen again, Government day clothes were issued and you were given a number, this number was your tooth brush number. [21]

George Bloomfield, a member of the Stolen Generations, was born in Melbourne in 1956 and remembers only fragments of his life with his parents before he and his siblings were taken by different police to different institutions. George was six when he arrived at the 'big and scary' Royleston Depot:

It was just like a mini-army for kids…you used to feel like you were in the Army. It was always strict. There was never any affection. We didn't show any affection. You know, we grew up pretty tough. [22]

A degree of regimentation was perhaps necessary, considering the large numbers of children passing through the institution, but residents complained that the home was utterly loveless:

I was trying to get some caring or love from anyone. I remember talking to the laundry lady and trying to get some caring from her but it seemed that all the adults in the place were totally cold to the children. [23]

Another resident told the Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee:

I was sent to Royleston Receiving Depot for Boys. It makes us sound like animals doesn't it? Societ[y's] rejects. Children rounded up and herded into depots where we could be sorted, placed and hidden away and forgotten about…I was told that I was sent there for my own good and that I was going to be there for a long time so I had better get used to it. If I was sent there for my own good then why did they treat me so bad? [24]

The elaborate interior of the house made for many dark corners in which terrible things happened to children. More than a few of the submissions to the Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee described sexual abuse by staff members occurring at Royleston in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. Former residents recalled being shut in a cupboard under the stairs, as punishment, and being frightened with stories of children who had escaped and been murdered nearby. [25] Sadly, some children never left Royleston but succumbed to childhood illnesses and died there. [26]

Postwar changes to Royleston

By 1955 the majority of boys in the home were aged six to ten years but older boys passed through the home on their way to other institutions. [27] By the 1970s fostering had become less common so boys stayed longer in Royleston and it became crowded, holding up to 43 boys at one time. In 1973 a teamwork approach was introduced involving psychologists and senior staff from the Department of Community Services. From this point, the home seems to have concentrated on slightly older boys.

Morri Young, a former worker at Royleston, wrote to the staff of the Find & Connect web resource to tell them his memories of the home. He said:

I was the Departmental officer responsible for supervising the manager and staff at this institution from 1981 to 1983. Royleston was a 'home' for adolescent, male wards. I recall it as a miserable, dark and cold place, with very little good to say about it. I was pleased to have a small part in its closure. [28]

Royleston today

Royleston was sold by the NSW Government in 1993. Its new owner removed the office partitions installed by the Department of Community Services and restored it to the grandeur it might have displayed during the era of the Carlsons and Kerrs. It operated for some years as a bed and breakfast called 'Tricketts'. [29] Today, neither the inside or the outside bear much relationship to the home experienced by generations of Forgotten Australians and members of the Stolen Generations.

Further reading

Find & Connect Web Resource Project for the Commonwealth of Australia, The Find & Connect web resource, 2011, www.findandconnect.gov.au

Bringing them Home Oral History Project, National Library of Australia, http://www.nla.gov.au/oral-history/bringing-them-home-oral-history-project

Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants Oral History Project and National Library of Australia, You can't forget things like that: Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants Oral History Project, Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2012.

Mellor, Doreen and Anna Haebich, eds. Many Voices: Reflection on Indigenous Child Separation, Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2002.

Notes

[1] Kristina Olsson, 'All the lost children', The Weekend Australian Magazine, 30–31 March 2013, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/features/all-the-lost-children/story-e6frg8h6-1226607413904, viewed 30 November 2014

[2] Heritage Branch, House 'Bidura' including interiors, former ballroom and front garden, State Heritage Inventory, NSW Environment and Heritage, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2427867, viewed 30 November, 2014

[3] Sands Directory, 1897, 260. The State Heritage Register listing for the house erroneously states that it was called 'Tricketts' at this time, but that name was conferred after 1993

[4] 'A Chinese Josshouse,' Evening News, 7 December 1898, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article114042629, viewed 29 November 2014

[5] Sands Directory, 1903, 320

[6] 'Obituary', Catholic Press, 11 August 1904, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article104918030, viewed 29 November 2014

[7] Sands Directory, 1910, 336

[8] 'Women's News', Sunday Times, 21 November 1920, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article120521118, viewed 29 November 2014

[9] State Records Authority of New South Wales, 'Royleston', http://search.records.nsw.gov.au/agencies/4178; 'Royleston', Agency Detail 506, State Records NSW, http://investigator.records.nsw.gov.au/entity.aspx?path=%5Cagency%5C506

[10] Sands Directory, 1923, 384

[11] Mancuso, Diane, 'Billy Billy', in Inside: Life in Children's Homes, National Museum of Australia, Australian Government, 5 September 2011, http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/115906/20111007-0000/nma.gov.au/blogs/inside/2011/09/05/billy-billy/index.html, viewed 28 November 2014

[12] Sands Directory, 1925, 346

[13] 'Local Event', Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 27 May 1925, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article137830380, viewed 29 November 2014

[14] Naomi Parry, 'Metropolitan Boys' Shelter (1911–1983)', Find and Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/nsw/NE00424, viewed 28 November 2014

[15] 'Mr. Walter Bethel', Sydney Morning Herald, 7 March 1929, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page1196755, viewed 28 November 2014; 'They'll All Enjoy Christmas Parties', Australian Women's Weekly, 9 December 1933, at http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/51188778, viewed 28 November 2014

[16] Naomi Parry, '"Such a Longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in NSW and Tasmania, 1880–1940', PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales, 2007, http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/4033481, viewed 25 November 2014; Peter Read, The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal Children in NSW 1883–1969 (Sydney: New South Wales Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs and Aboriginal Children's Research Project, NSW Family and Children's Services Agency, 1981)

[17] Naomi Parry, '"Such a Longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in NSW and Tasmania, 1880–1940.' PhD Thesis, UNSW, 2007, http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/4033481, viewed 25 November 2014; Peter Read, The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal Children in NSW 1883–1969 (Sydney: New South Wales Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs and Aboriginal Children's Research Project, NSW Family and Children's Services Agency, 1981)

[18] Christine Kenneally, 'The Forgotten Ones: half a million lost childhoods', The Monthly, 81 (August) 2012, http://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2012/august/1354057131/christine-kenneally/forgotten-ones, viewed 14 November 2014

[19] New South Wales Child Welfare Department, Report of the Minister of Public Instruction on the work of the Child Welfare Department, (Sydney: Department of Education, 1936)

[20] Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee, Forgotten Australians: A report on Australians who experienced institutional or out-of-home care as children, (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2004), 53, http://www.aph.gov.au/~/media/wopapub/senate/committee/clac_ctte/completed_inquiries/2004_07/inst_care/report/report_pdf.ashx, viewed 28 November 2014

[21] Submission 321, in Senate Community Affairs Committee, Inquiry into Children in Institutional Care – Submissions received by the committee as at March 17, 2005 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2005), http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/inst_care/submissions/sublist, viewed 14 November 2014

[22] George Bloomfield interviewed by John Maynard in the Bringing them home oral history project (2001), http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn887596, cited in Lorena Allam, 'Memories of Home', in Mellor, Doreen and Anna Haebich, eds. Many Voices: Reflection on Indigenous Child Separation, (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2002), 31

[23] Submission 150, in Senate Community Affairs Committee, Inquiry into Children in Institutional Care – Submissions received by the committee as at March 17, 2005 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2005), http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/inst_care/submissions/sublist, viewed 14 November 2014

[24] Submission 94, in Senate Community Affairs Committee, Inquiry into Children in Institutional Care – Submissions received by the committee as at March 17, 2005 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2005), http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/inst_care/submissions/sublist, viewed 14 November 2014

[25] Submission 94, 'Submission 150', 'Submission 321', in Inquiry into Children in Institutional Care – Submissions received by the committee as at March 17, 2005, (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2005), http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/inst_care/submissions/sublist, viewed 14 November 2014

[26] 'Meningitis Case Suspected At Welfare Home', Canberra Times 21 June 1957, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91591593, viewed 30 November 2014; Mancuso, Diane, 'Billy Billy', in Inside: Life in Children's Homes, National Museum of Australia, Australian Government, 5 September 2011, http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/115906/20111007-0000/nma.gov.au/blogs/inside/2011/09/05/billy-billy/index.html, viewed 28 November 2014

[27] Donald McLean, Children In Need: An account of the administration and functions of the Child Welfare Department, New South Wales, Australia: with an examination of the principles involved in helping deprived and wayward children (Sydney: Government Printer, 1955)

[28] Morri Young, email to the Find & Connect web resource, cited in Naomi Parry, 'Royleston', Find & Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE00432b.htm, viewed 21 November 2014

[29] Personal communication with owner, cited in Naomi Parry, 'Royleston', Find & Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE00432b.htm, viewed 21 November 2014