The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Scots

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Scots

Although it is [media]sometimes said of nineteenth-century Sydney that it was an English city, in contrast with the more Scottish city of Melbourne, people of Scottish origin have played important roles in the development and life of Sydney. They have been there from the very beginning: young Forby Sutherland, one of Captain Cook's crew in 1770, was the first Briton to be buried in Australia, in a district now bearing his name. Major Robert Ross of the Marines and Captain John Hunter were among several Scots on the first fleet in 1788. Scots formed a small minority of convicts transported (perhaps 5 per cent) and were among the earliest free settlers in the 1790s.

The early years

The [media]foundation of Sydney coincided not only with the expansion of the British Empire but also with the heyday of the Scottish enlightenment and the onset of agricultural, industrial and political revolutions. Scotland contributed so liberally to the military and civil service of the Empire that it is no surprise to find many Scots in the Army, the Commissariat and among the surgeons.

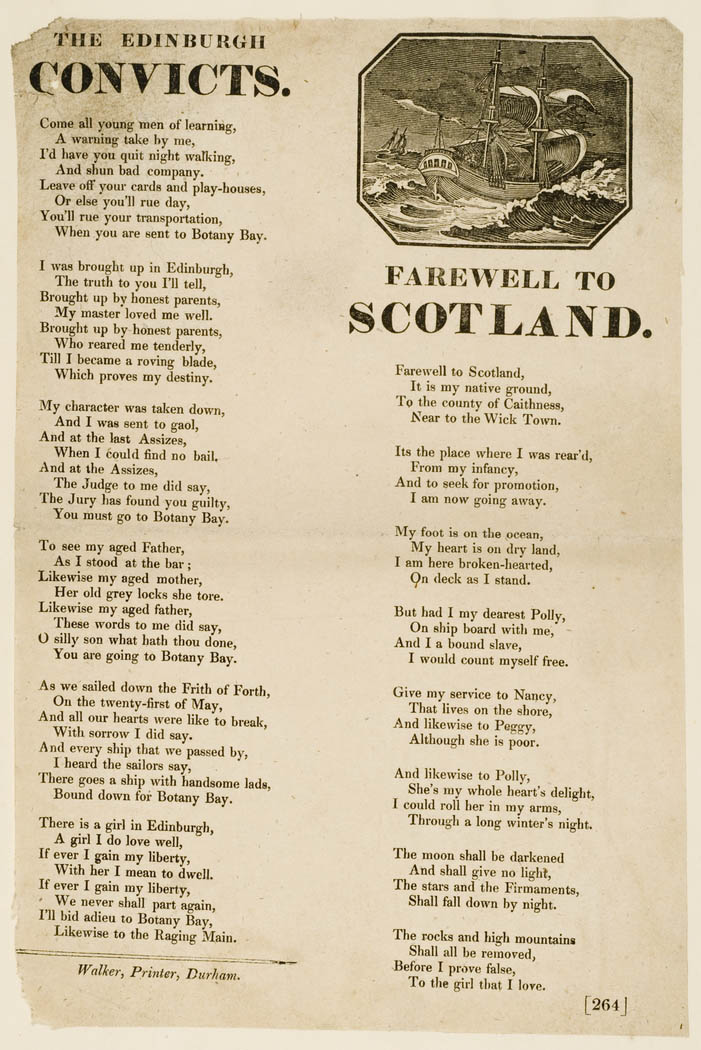

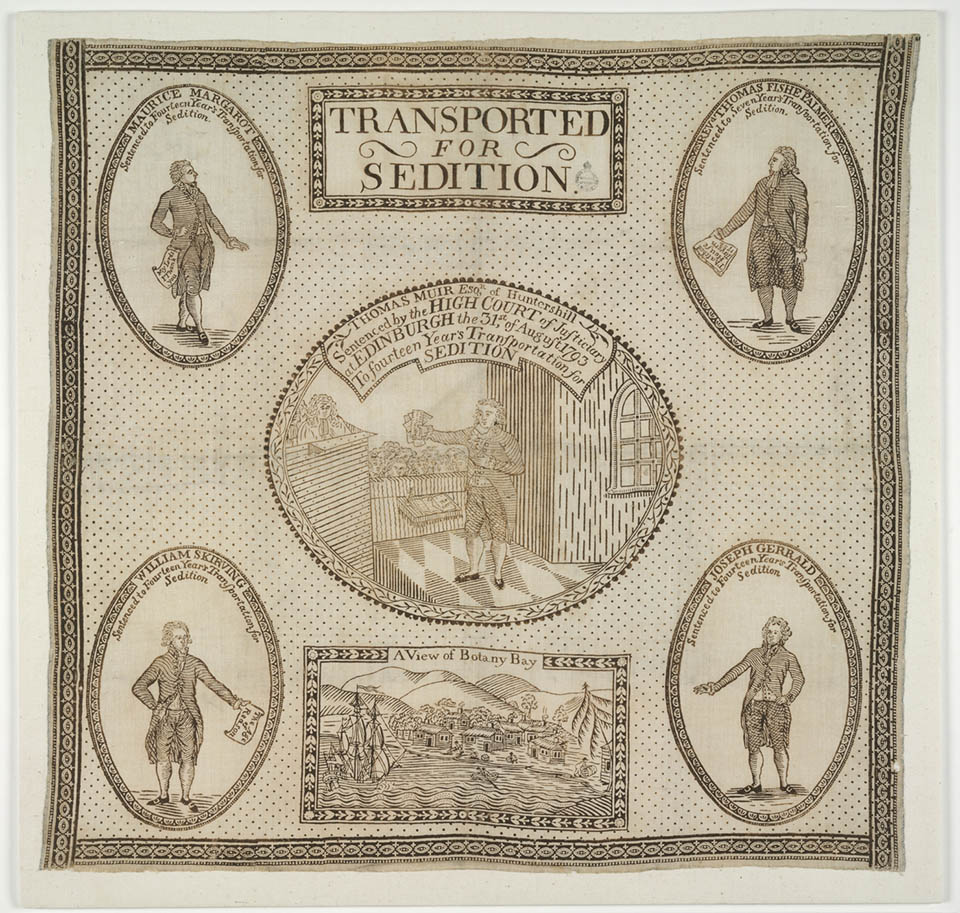

[media]Though there were few Scots convicts, they included the 'limner of Dumfries', Thomas Watling, who left a valuable artistic record of early Sydney, and the Borderer Andrew Thompson who became a wealthy landowner and magistrate. [1] The four 'Scottish Martyrs' (and one or two later) were transported from Scotland in 1794 for sedition. Radical liberals Maurice Margarot, TF Palmer, William Skirving and Thomas Muir enlivened early Sydney. [2] Muir is credited with inaugurating Presbyterian worship in Sydney. [3] The 19 Scottish Radicals who were transported in 1820 were mainly skilled tradesmen and contributed to the economic and educational life of the Sydney region. [4]

Ebenezer was the centre of a partly Scottish community on the Hawkesbury from 1802. The church was the first built in Australia by private endeavour and is now the oldest still standing. [5] Scots were also prominent among early Sydney merchants from the 1790s, such as Robert Campbell, Alexander Berry, and Archibald Mosman of whaling fame.

Governors and administrators

Two very different Scots occupied Government House for a decade and a half, from 1809 to 1824. Lachlan Macquarie came from a good Highland family which was poor in money and connections, whereas Sir Thomas Brisbane was a lowlander from a landed family with good connections. Macquarie's enlightened reform and planning agenda owed much to the evangelicalism and enlightenment thinking prominent in Scotland at the time. [6] Brisbane was an improver in a different but equally characteristically Scottish way, as well as a keen scientist who promoted astronomy in particular. [7] He recruited James Dunlop from Ayrshire, who worked at Parramatta Observatory from 1821 to 1847.

Macquarie and Brisbane were both able to use their influence to gain positions in the colony for their countrymen. From the 1820s, many Scots filled important military and civil administrative roles. The three Colonial Botanists of New South Wales from 1819 to 1839 were Scots, Charles Frazer, Richard and Allan Cunningham. Such Scots as these and their descendants often went on to be influential in Sydney's political, commercial and cultural life. Macquarie also contributed to the array of Scottish placenames – including Campbelltown, Appin, and Ben Buckler.[media] The important position of Colonial Secretary was held by Alexander Macleay (1825–37) and Edward Deas Thomson (1837–56). Free immigration of Scots also began to accelerate in the 1820s.

The Presbyterian church

[media]The Reverend John Dunmore Lang was the most famous (or notorious) Scot in nineteenth-century Sydney. [8] He arrived in Sydney in 1823 and set about organising the Presbyterian cause, in which he was later to cause periodical divisions and schisms. Very early, Lang clashed with a compatriot, Governor Brisbane, whose anglophile response to an application for the funding of a church of the established Church of Scotland riled Lang. Scots Church was built in 1826 and Lang was its minister until his death in 1878. (The original building was demolished to make way for the harbour bridge approaches. It was replaced by the impressive 'interwar gothic' Assembly Hall, incorporating the church, in Margaret Street.) Lang clashed with the second minister, John McGarvie, who became minister of a second Sydney Presbyterian church, St Andrew's Scots, located behind the Anglican cathedral site. [9] Lang was a man of schemes. He organised immigration, sometimes at his own expense. His 'Scotch mechanics' of 1831 were a valuable addition to Sydney's skilled workforce at the time. In politics, he was an outspoken democrat, republican and liberal. His protégé, John Robertson, became a dominant figure in New South Wales politics. In gratitude for his opposition to the poll tax, many Chinese joined Lang's huge funeral procession in 1878. A statue of this 'statesman and patriot' was erected in Wynyard Park.

The predominantly Presbyterian Scots brought their faith with them and they established churches throughout city and suburbs. The history of the Presbyterian Church in New South Wales is very complex but from the 1830s, a regional church court, called a presbytery, governed the Sydney parishes. Gradually, the Presbytery of Sydney was divided and subdivided, eventually into six suburban presbyteries governing over a hundred parishes. Within the metropolitan area, church parishes and buildings spread as settlement spread, with particularly strong surges in the 1850s, 1880s, 1920s, 1950s and 1960s. Particular areas of strength emerged, at one time the inner western suburbs (such as Ashfield), then the eastern suburbs (Woollahra), the southern suburbs (Hurstville) and later along the north shore (Wahroonga) and northern [media]lines (Epping). For many decades, the local church was an important venue for the continuation of Scottish traditions, like country dancing. It also inculcated civic values and encouraged democratic participation. Those Presbyterian churches which have names generally hark back to Scottish tradition: Knox, Chalmers and Scots Kirk being the most common, along with Saints Andrew, Columba, Giles, Margaret and Ninian. The main city church, St Stephen's (now Uniting Church) opposite Parliament House, has had Scottish ministers for much of its long history. [10] Its minister in the 1950s and 1960s, the Reverend Gordon Powell, became very well known partly through his popular mid-week services and radio broadcasts. [11] St Andrew's College at the University of Sydney housed the Theological Hall from the 1870s to the 1970s.

Education

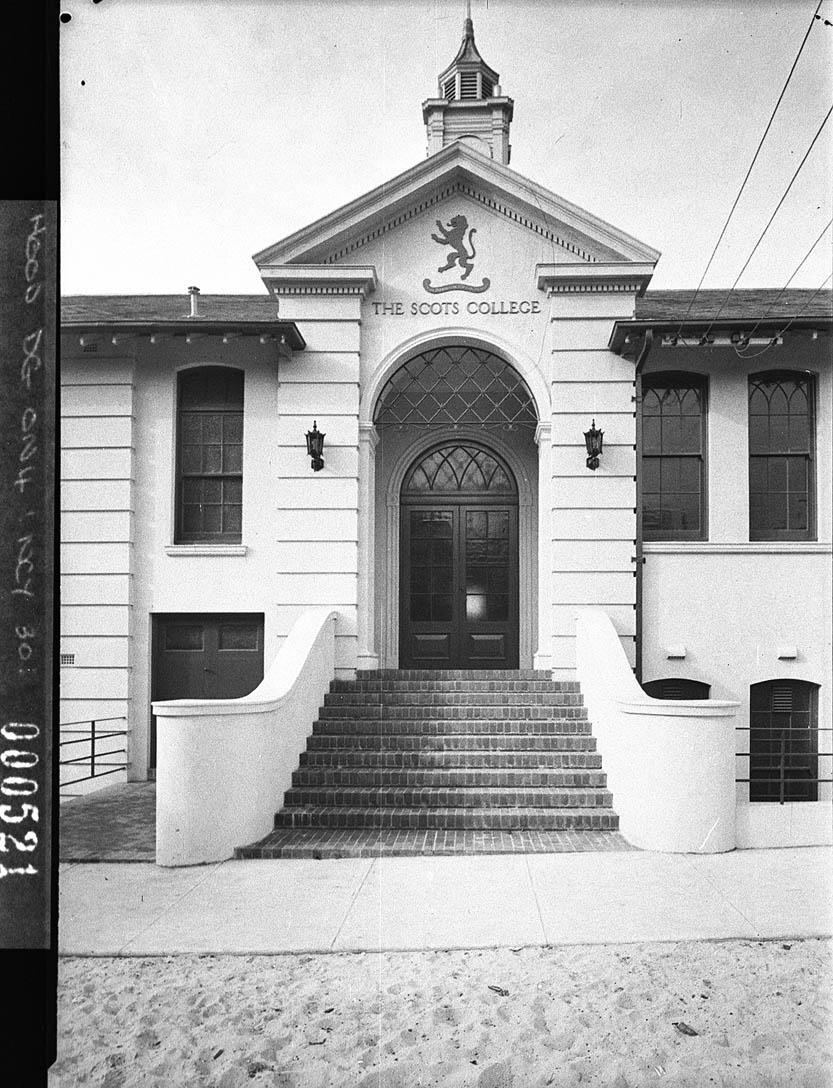

Scots had a proud tradition of education and took it to the Empire. JD Lang started many schools, including the first post-secondary institution, the Australian College. Presbyterian schools had been numerous before the 1860s but were swallowed up by the state system. In the 1880s, the Church began again with secondary schools: Presbyterian Ladies College (1888, later at Croydon) and Scots (1893, later at Bellevue Hill). In the early 1900s, there was a private Knox College in North Sydney and St Andrew's School at Manly in the 1940s. After the Great War, Presbyterian Ladies College Pymble (1916) and Knox Grammar School (1924) followed, but a proposed St Columba's Grammar School at North Parramatta was aborted in the 1930s. These schools all exhibited Scottish trappings such as pipe bands, badges containing Scottish symbolism, uniforms featuring Black Watch tartan and kilted army cadets. [media]The Scots College motto was devised by one of the Scottish founders and refers to his heritage: Utinam Patribus Nostris Digni Simus (O that we may be worthy of our forefathers). [12]

In 1901, Scots and Scottish-Australians were disproportionately represented among teachers in Sydney and suburbs. Around the turn of the century, the modernisation of New South Wales schooling had much to do with the advocacy and work of three Scottish Australians: Peter Board, Francis Anderson and Alexander Mackie. [13] One of the most famous schoolmasters of the era was AJ Kilgour of Fort Street, 1905–26. [14] Peter Dodds McCormick (1833–1916) emigrated from Glasgow in 1855 and became a teacher, an elder and precentor in the Presbyterian Church and a prominent member of a number of Scottish societies. He conducted church and school choirs. In 1874, coming home from a concert on a horse-drawn bus, he scribbled down a first draft of 'Advance Australia Fair', much later to become Australia's national anthem. [15]

The University of Sydney was organised largely along Scottish lines, even though the trappings were English in inspiration. Aberdonian John Smith was Professor of Chemistry and Physics at the university from 1852 to his death in 1885. He was on the boards of many companies and charities. The first professors of medicine, geology, philosophy, modern literature, education, economics, zoology, veterinary science and agriculture, as well as the second but more important Professor of Philosophy, were Scots. The importance of philosophy in the Scottish university model is perhaps reflected in the fact that three Scots held the philosophy chair for 66 years between 1890 and 1963. HS Carslaw was Professor of Mathematics for 32 years and had a building named after him. Scots have been vice-chancellors for a total of 58 years, including Sir Robert Wallace (1928–47) and Gavin Brown (1996–2008). [16]

Medicine and public health

Considering the reputation of Scottish medical education, it is not surprising that the founders of the medical school at the University of Sydney were Edinburgh graduates, Sir Thomas P Anderson Stuart and TS Dixson. They were followed by many other Scots, such as Robert Scot Skirving, Alexander McCormack and JT Wilson. Scots have filled the chair of anatomy for half the time since it was created in 1890. Belfast-born but Scottish-educated Francis Campbell was the first medical superintendent of Sydney's Tarban Creek Asylum from 1848 to 1867. Scottish doctors have continued to be common in Sydney, particularly as specialists.

During and after the plague outbreak in 1900, two Scots were very involved with affected areas. James Mathers was Sydney City Missionary in The Rocks and Millers Point and continued working there throughout. [17] Architect–engineer George McCredie was in charge of the quarantine and cleansing operation. Both men were devout Presbyterians and no doubt saw their different duties as equally vocational.

Business life

Scots were quite prominent in Sydney business life, especially trade, finance and manufacturing. [media]Place names like Ashfield, Campbells Cove, Campsie, Berrys Bay, Hunters Hill and Mosman Bay indicate the involvement in Sydney life and maritime trade, of such Scots as Robert Campbell, Alexander Berry and Archibald Mosman. Scots were later also prominent in stevedoring and shipping firms, such as Burns Philp, Patrick's and Gilchrist & Watt.

The first bank in Australia, the Bank of New South Wales, was founded in 1817 with the encouragement of Macquarie and its first chief executive was an Ulster-Scot, JT Campbell. The Commercial Banking Company of Sydney was founded in 1834 on an explicitly Scottish basis by Lesslie Duguid. Especially in its early years, directors and executives were disproportionately Scottish, including long-time general manager, TA Dibbs, brother of future Premier, Sir George. Scots have been plentiful in Sydney's finance industry ever since.

Most of the actuaries who were important to Sydney's early insurance companies were either Scottish-born or educated. Robert Thomson, a Scottish-educated Ulsterman was with the AMP for nearly 15 years, later founding Colonial Mutual Life in 1873. His successors at the AMP included MA Black (1868 to 1890) and David Carment. Andrew Sneddon, the son of a Scottish blacksmith, combined the roles of general manager and actuary for the AMP up to the 1940s.

Several Sydney-based businesses were started by or managed by Scots. They were strongly represented in Colonial Sugar Refineries. Archibald Forsyth was a leading rope manufacturer, Hugh Dixson was the leading nineteenth-century tobacco manufacturer and Andrew Reid was effective founder of James Hardie & Company.

John Busby, a Scottish engineer, constructed 'Busby's Bore' in the 1830s to supply Sydney with water. Sir Peter Nicol Russell in the late nineteenth century was Sydney's leading iron founder and engineer: he richly endowed the school of engineering at the University of Sydney. Stonemasons recruited from Aberdeenshire worked on the pylons of the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Sport

Scots have participated widely in Sydney's sporting life. Golf was pioneered by Scots, and the first course and club in Sydney was founded in 1855 near Concord by solicitor John Dunsmore who brought his equipment out from St Andrews itself. Though lawn bowls was played all over the United Kingdom, Australia tended to follow the Scottish style. After a false start in the 1840s, bowls also got under way in New South Wales in the 1860s, when a Scottish tailor, Alexander Johnstone, introduced the game under modern club conditions.

Australian soccer started in Sydney and the first cup final was held at Botany in September 1885. Caledonians went down to Granville (where Clyde engineering employed many Scots); 19 of the 22 players on the pitch that day were Scots. Soccer was sustained in pre-1945 Sydney predominantly by Scots and northern English immigrants. Though there were old clubs with Scottish associations, like Arncliffe Scots, the postwar Scots footballers played for clubs of any ethnic label providing the money was good. Indeed, Australian soccer clubs recruited more soccer players from Scotland between 1965 and 1985 than from any other country, and many of them came to Sydney clubs.

Culture

In the 1850s and 1860s, Scottish lawyer Nicol Drysdale Stenhouse (1806–73) of Balmain was a great promoter of literary culture in Sydney. He was involved in the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts from 1855 to his death, a committee member at the Australian Library and Literary Institution 1857–69, trustee of the Free Public Library 1869–73, a trustee of the Sydney Grammar School in 1866, a member of the University Senate in 1869 and an alderman of Balmain Municipal Council. He was a devout Presbyterian. [18] Encouraged by two other Scottish-Australians, George Robertson the bookseller and HCL Anderson the librarian, David Scott Mitchell left to Sydney and the country the greatest library of Australiana in the world. Angus & Robertson, bookseller and publisher, was a firm that was thoroughly both Scottish and Australian.

Dundee-born Charles Moore was director of the Sydney Botanic Gardens from 1848 to 1896. Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art from 1999 has been Scot Elizabeth Ann Macgregor, who has a penchant for tartan.

Sydney's place in the history of Australian rock music was enhanced by Scots immigrants in the 1960s and 1970s. The Young family from Glasgow contributed George to the Easybeats and Angus and Malcolm to AC/DC. John Paul Young (no relation) was another musical Scot, as was jazz singer Vince Jones.

Scots culture and traditions

As early as the 1820s, there was a St Andrew's Club in Sydney. According to John Dunmore Lang, it failed because of its 'purely convivial character', devoid of any benevolent intent. In 1836 and 1837, balls were held on St Andrew's Day (30 November), attended by 300 guests including the Governor, the dancing lasting until three in the morning. [19] In 1839 in Sydney a more organised Caledonian Society began but it faltered in the depression of the early 1840s. The St Andrew's Society of New South Wales struggled on for several years.

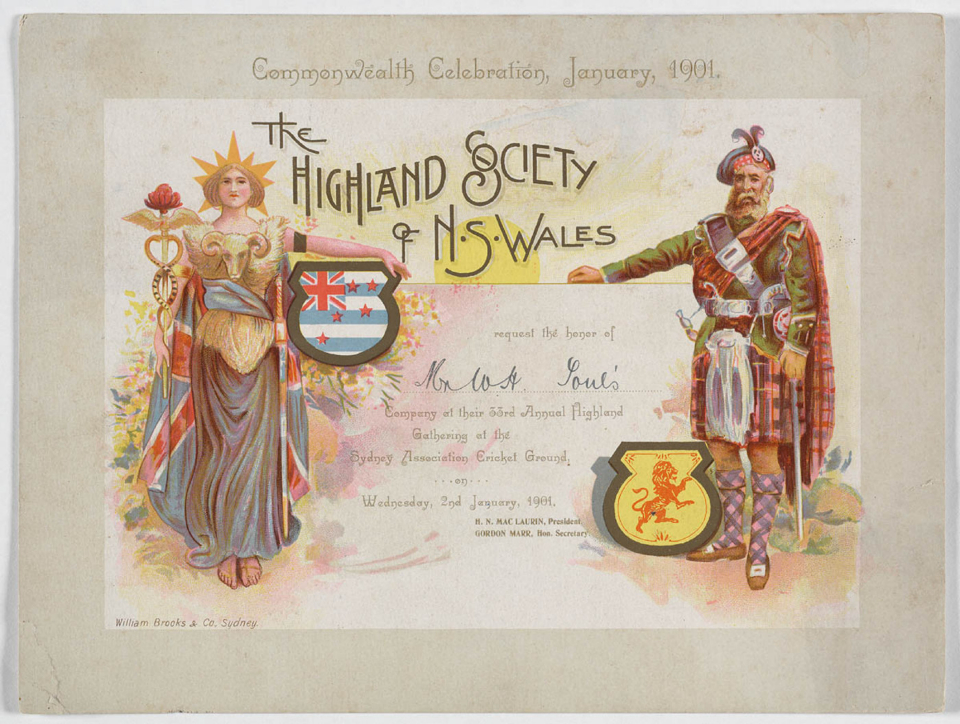

Another [media]Caledonian Society was formed in 1874 but, by 1876, this society and the Gaelic Society were both struggling and began to discuss amalgamation. The Highland Society of New South Wales was established in 1877 by this merger. Its founding office-bearers included Sir John Hay, the President of the Legislative Council and five other MPs. Also a member was the Chinese restaurateur Quong Tart, well-known for singing Scottish songs while in highland dress – earning him the soubriquet 'Quong Tartan'. [20] The Society organised an annual gathering and games on New Year's Day for many years.

Scots and Scottish Australians in Sydney have maintained traditional celebrations such as Hogmanay (New Year), Burns Night (25 January), Halloween (31 October) and St Andrew's Day (30 November). The Presbyterian suspicion of saints had lessened the importance of the latter two; ironically the pagan Hogmanay continued more strongly, but the most popular and widespread has been Burns Night. These celebrations are relatively more important to Scots in Australia than in Scotland, except for Hogmanay.

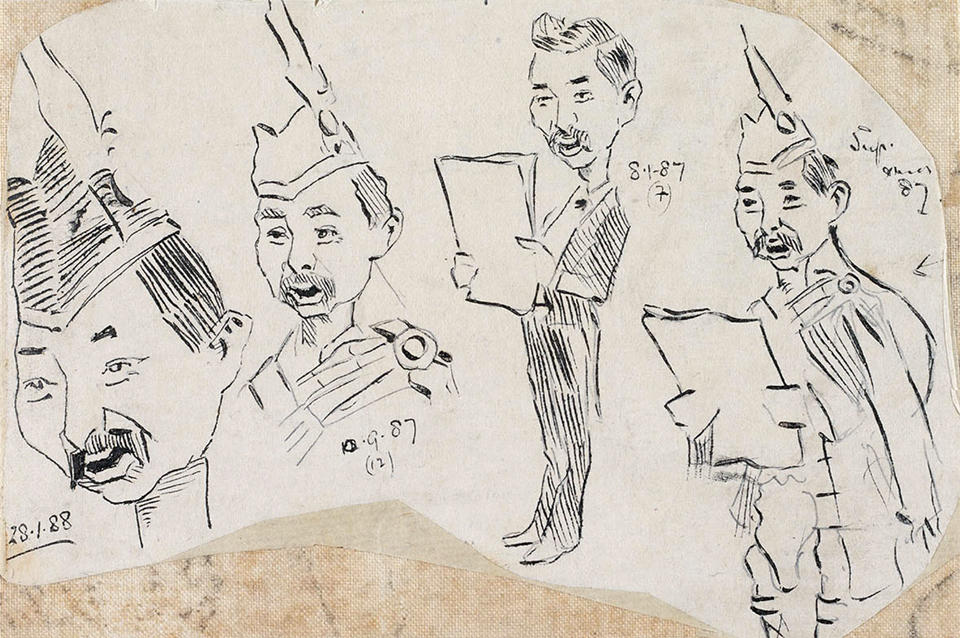

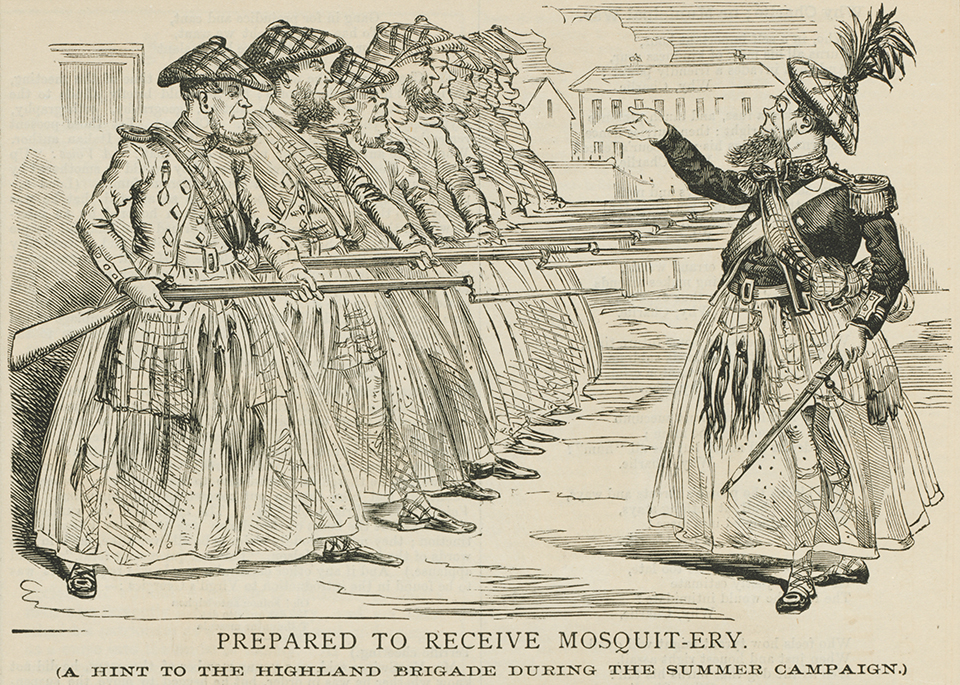

In the [media]aftermath of the attempted assassination of Queen Victoria's son, Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, in 1868, the Duke of Edinburgh's Highlanders was raised in Sydney, but only lasted 10 years. The Sudan crisis in 1885 seems to have prompted the formation of the Sydney Reserve Corps of Scottish Rifles at a public meeting chaired by Sir Normand MacLaurin. [media]In 1889 the Sydney Scottish Rifles first appeared in full-dress uniform, with kilt. [21]

Over the years, many pipe bands have been established. In the 1910s and 1920s, with strong Scottish immigration to industrial areas, the Scottish population of Sydney, especially in the western suburbs, increased. This is reflected in the spread of suburban Caledonian societies and pipe bands in the interwar years. Presently, there are about 20 bands based in the Sydney metropolitan area, connected with schools, the Army, RSL clubs and districts. Anzac Day celebrations would not be the same without the skirl of the pipes.

Gaelic language and culture

The tiny minority of Scots in Sydney who were Gaelic-speaking Highlanders had an uphill battle to preserve their language and culture. For many years, Gaelic preaching could be heard at St George's 'Free Church', Castlereagh Street.[media] The Gaelic Society in Sydney met first in November 1875, with the aim of preserving the Gaelic language and literature, especially poetry, and the history and romance of the Scottish Highlands. Though very active in its first year, the society's attendance dropped and the group had to merge with the lowlanders in the diplomatically named Highland Society of New South Wales.

Another Gaelic Society had a fleeting existence in Sydney in the 1940s but organised promotion of Gaelic lapsed again. With more enthusiasm about Celtic cultures in the 1970s, Gaelic classes started in Sydney. Comhairle Gaidhlig Albannach (The Council for Scottish Gaelic) sought to promote Gaelic language and culture and revived the newspaper An Teachdaire Gaidhealach after 124 years (1981–90). A Scottish Gaelic programme commenced on radio station 2EA in 1982. In the same year, Còisir Ghàidhlig Astrailianach (the Australian Gaelic Singers) began in Sydney. A Sydney branch of An Comunn Gaidhealach (The Gaelic Society, founded in Scotland in 1891) began in 1984 and revived An Teachdaire Gaidhealach again in 1998.

The 1980s [media]saw a surge of Caledonian enthusiasm on the part of Scottish-Australians and the bicentennial in 1988 saw the erection of a commemorative Scottish-Australian cairn at Mosman, overlooking the harbour. It contains a stone from every parish in Scotland. Scottish Week has been held in Sydney since the 1980s, generally around the time of St Andrew's Day, 30 November. The 'Kirking of the Tartan', a newly invented tradition, has been celebrated in a few Sydney churches in recent years.

Invisible contributors

Though in 2006 there were 242,022 people in Sydney claiming Scottish ancestry, the Scots are sometimes dubbed 'invisible immigrants' because they have not generally been conspicuous as a group. They have never formed anything resembling a ghetto and have been very dispersed socially and geographically, usually adapting speedily. The presence of the Scots only becomes obvious through specifically Scottish events, such as highland games, although it must be admitted that participants in such activities are more likely to be locally-born Scots descendants rather than more recent immigrants. To the extent that food is a marker of ethnic identity, Scots are again almost invisible, though they become more visible occasionally when eating haggis on Robbie Burns's birthday. Individually, of course, many thousands of Scots have made contributions to the life of Sydney over its entire history, in every conceivable location and in every way possible.

References

MJ Buckley, Scarlet and Tartan: The Story of the Regiments and Regimental Bands of the New South Wales Scottish Rifles, The Red Hackle Association, Sydney, 1986

GW Hardy, Living Stones: the story of St Stephen's, Anzea, Sydney, c1985

M Hutchinson, Iron In Our Blood. A History of the Presbyterian Church in New South Wales, 1788–2001, Ferguson Publications and the Centre for the Study of Australian Christianity, Sydney, 2001

ME and AD MacFarlane, The Scottish Radicals: Tried and Transported to Australia for Treason in 1820, Wentworth Books, Sydney, 1975

MD Prentis, The Scots in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2008

The Scottish Australasian, 1910–52, published in Sydney by the Highland Society of New South Wales

Notes

[1] MD Prentis, 'What do we know about the Scottish convicts?' Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, 90, 1, June 2004, pp 36–52

[2] F Clune, The Scottish martyrs; their trials and transportation to Botany Bay, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1969, esp 144, 161–62; John Earnshaw, 'Muir, Thomas (1765–1799)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 2, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1967, pp 266–267

[3] CA White, The Challenge of the Years: A History of the Presbyterian Church of Australia in the State of New South Wales, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1951, pp 1–2, quoting JG Lockhart, 'A skeleton in the cupboard', Blackwood's Magazine, 268, July 1950, pp 43ff

[4] ME and AD MacFarlane, The Scottish Radicals: Tried and Transported to Australia for Treason in 1820, Wentworth Books, Sydney, 1975

[5] GRS Reid, The Story of Ebenezer, Australia's Oldest Church, Portland Head, Hawkesbury River, near Windsor, Presbyterian Church of Australia, Sydney, 1938

[6] JD Ritchie, Lachlan Macquarie: A Biography, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986. See L Coltheart and P Bridges, 'The elephant's bed? Scottish Enlightenment ideas and the foundations of New South Wales', in W Prest and G Tulloch (eds), Scatterlings of Empire, Journal of Australian Studies, 68 2001, pp 19–33, 220–23

[7] C Liston, 'Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane – a background study', Descent, 11, March 1981, pp 4–16

[8] DWA Baker, Days of Wrath: A Life of John Dunmore Lang, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1985

[9] BJ Bridges, 'The Rev Dr John McGarvie', parts 1 and 2, Church Heritage, 4, 4, September 1986, pp 230–44 and 5, 1, March 1987, pp 1–17

[10] M Hutchinson, Iron In Our Blood A History of the Presbyterian Church in New South Wales, 1788–2001, Ferguson Publications and the Centre for the Study of Australian Christianity, Sydney, 2001

[11] GG Powell with John Bodycomb, Gordon Powell Reflects, Spectrum Publications, Melbourne, 2006

[12] GE Sherington and MD Prentis, Scots to the Fore: A History of The Scots College Sydney 1893–1993, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1993

[13] AR Crane and WG Walker, Peter Board: His Contribution to the Development of Education in New South Wales, Australian Council for Educational Research, Sydney, 1957

[14] DL Webster, 'Kilgour of Fort Street: The English headmaster ideal in Australian state secondary education', in S Murray-Smith (ed), Melbourne Studies in Education 1981, Melbourne University Press 1981, pp 184–200; and AR Chisholm, Men Were my Milestones, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1958, pp 24–32

[15] MD Prentis, The Scots in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2008, chapter 15

[16] C Turney, U Bygott and P Chippendale, Australia's first: a history of the University of Sydney, The University of Sydney in association with Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991

[17] MD Prentis, 'City of Man, City of God: Images of a Slum, 1897–1911,' in L Finch and C McConville (eds), Gritty Cities: Images of the Urban, Pluto Press, Sydney, 1999, pp 97–115

[18] A-M Jordens, The Stenhouse Circle: Literary Life in Mid-Nineteenth Century Sydney, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1979

[19] G Abbott and G Little (eds), The respectable Sydney merchant, AB Spark of Tempe, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1976

[20] The Life of Quong Tart, or, How a foreigner succeeded in a British community , compiled and edited by Mrs Quong Tart, WM Maclardy, Sydney, 1911

[21] MJ Buckley, Scarlet and Tartan: The Story of the Regiments and Regimental Bands of the New South Wales Scottish Rifles, The Red Hackle Association, Sydney, 1986, pp 3–8, 228, 284–86

.