The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The end of transportation

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The end of transportation

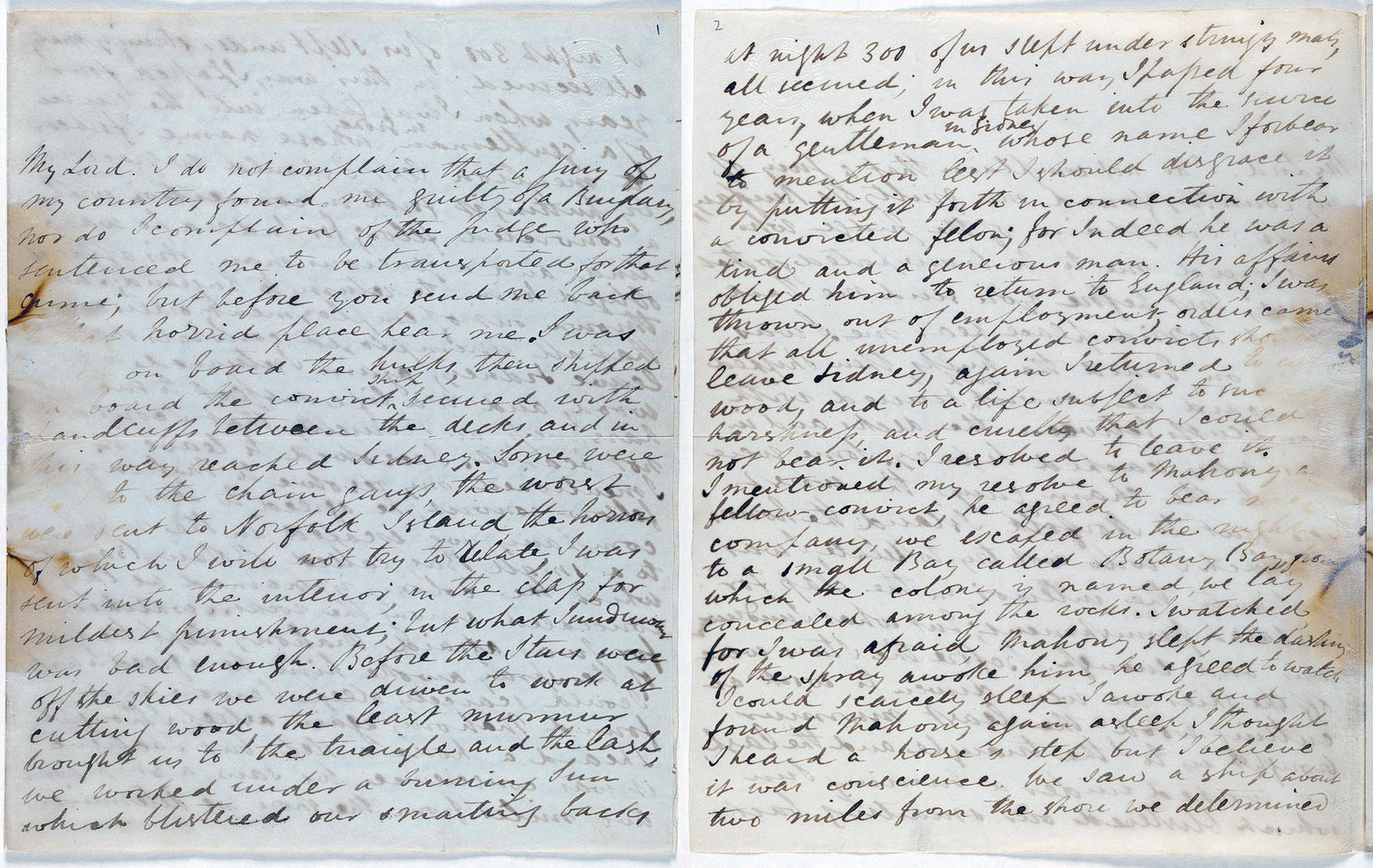

The anti-transportation movement was one of the first and strongest political movements that bound the people of Sydney. Henry (later Sir Henry) Parkes cut his political teeth in the anti-transportation speeches of the late 1840s. [media]On a wet day in 1849, between 7,000 and 8,000 Sydneysiders turned up to an anti-transportation rally held at Circular Quay to protest at the landing of the Hashemy, a convict transport. In 1851, at Barrack Square, Wynyard, there was another huge rally against transportation, to defend those in Van Diemen's Land who sought its permanent abolition. A petition was signed by 16,000 people.

Opposition to transportation

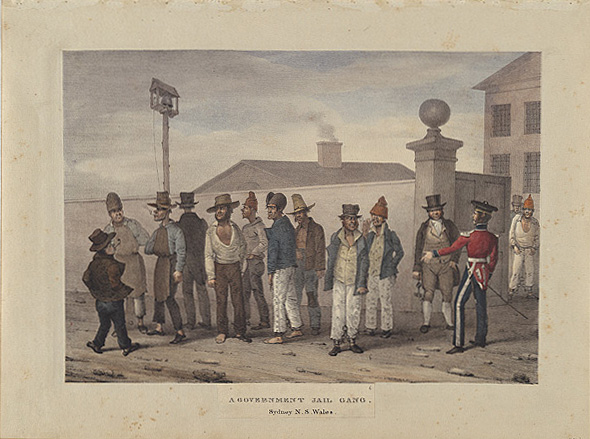

[media]Until the 1830s, not many people disagreed with the proposition that transportation was an efficient and acceptable system for criminal punishment. Through the 1830s however, newly emerging humanitarian and liberal views were gaining a foothold in British political life. As the British penal code became less harsh, it was, as a rule, only the more dangerous and hardened criminals who committed offences that were punishable by transportation. A deepening gulf developed between the newly arrived convicts and the rest of Sydney's population.

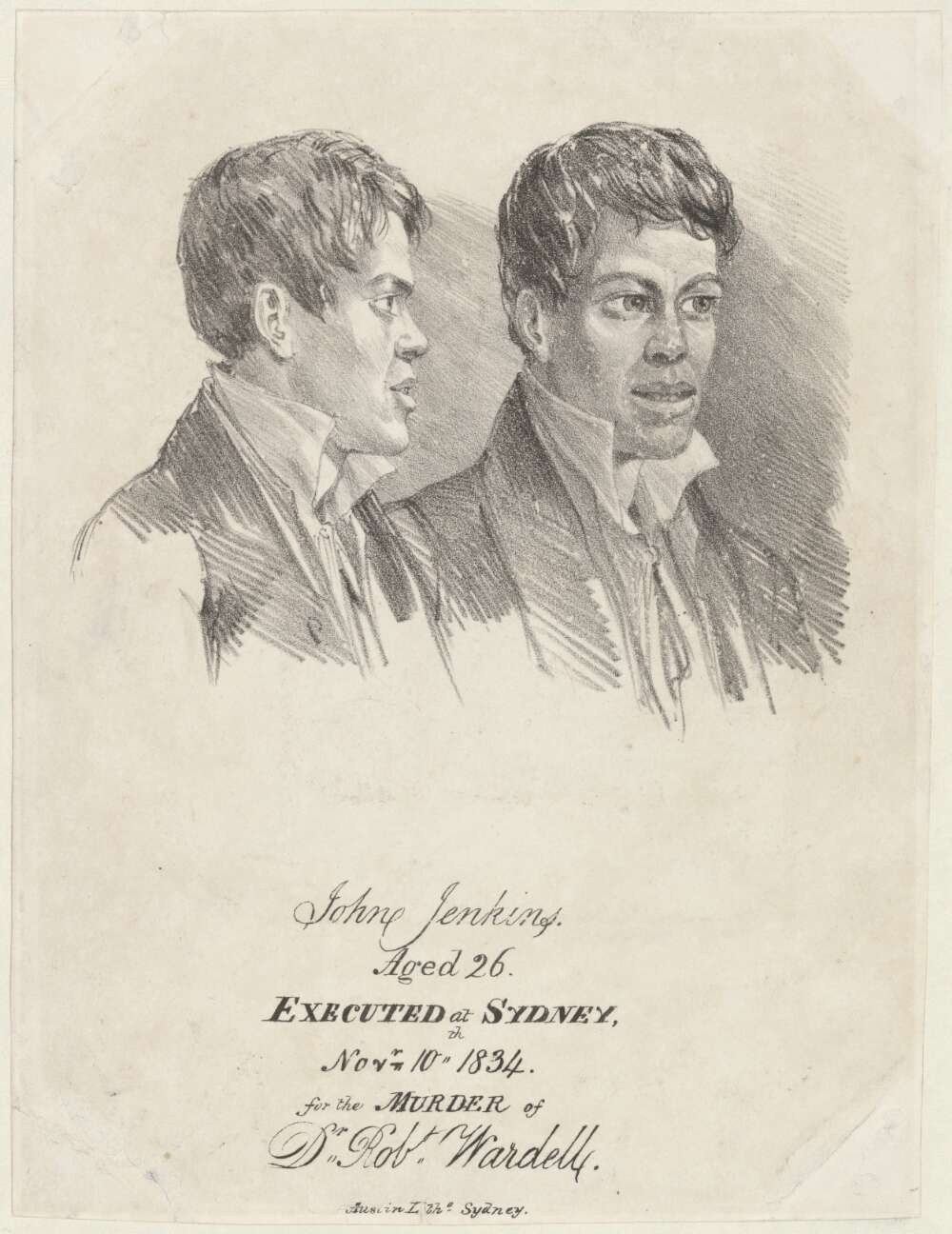

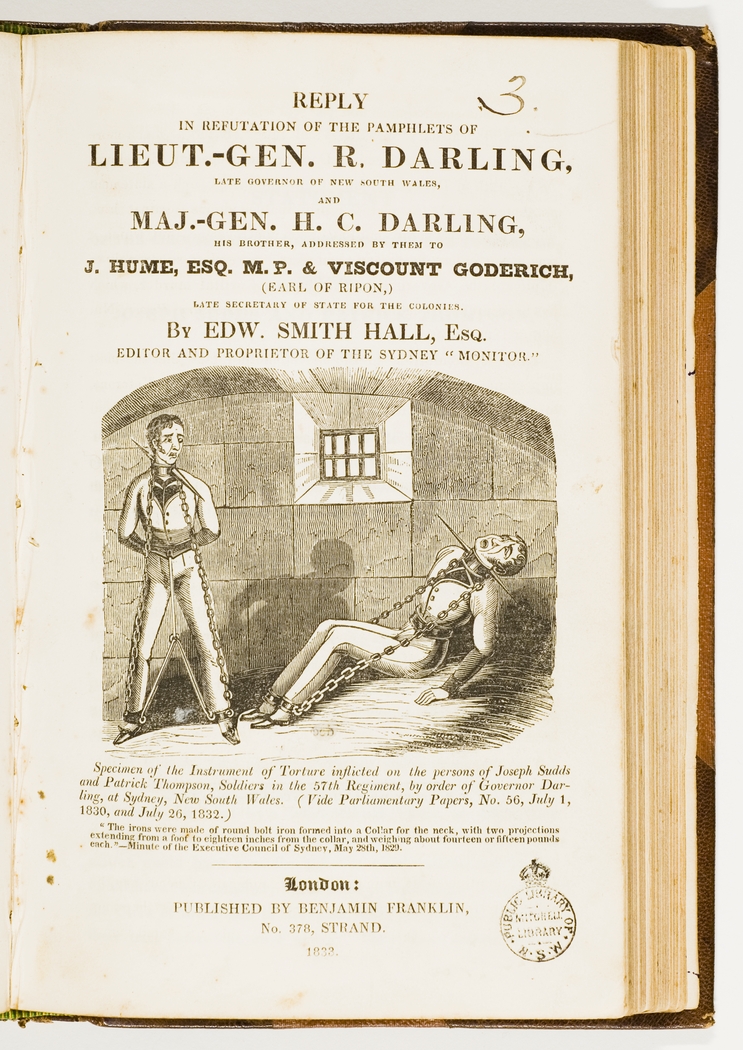

[media]Crimes committed by escaped convicts roaming the countryside, such as the murder of Robert Wardell, the friend and business partner of WC Wentworth, on the Cooks River in 1834, led many to believe that transportation was neither desirable nor necessary. Assigned convicts, it was argued, were lazy, unreliable and dangerous. There was now also a readily available supply of voluntary immigrant labour. Newspapers wrote of a growing crime wave (not for the first or last time) fed by disgruntled and desperate convicts who threatened the fabric of colonial society.

Political prisoners

[media]One exception to the rule that the convicts who arrived in the 1830s were more hardened than those that had been transported earlier were political prisoners, such as the Swing Rioters. These people were part of a relatively widespread revolt by farm labourers opposed to the high price of grain in Britain. They took out their fury by burning the stores of grain they could not afford to buy. They also protested against the mechanisation of agriculture by vandalising their new enemy – the machines. It was considered a fitting punishment to remove these people from society. Canadian political prisoners were sent out in the late 1830s as well. Like the Swing Rioters, many of these men were skilled tradesmen whose talents were quickly put to use at [media]Victoria Barracks and elsewhere. The suburb of Canada Bay on the Parramatta River is named after them.

Opposition to transportation grew during the 1830s. The main opponents to it were the urban-dwelling, immigrant middle and working classes. Those who most strongly favoured transportation were wealthy squatters and landowners who were heavily dependent on cheap convict labour.

The Molesworth Committee

In 1837, the Molesworth Committee was convened in England to report on transportation and its future. Evidence about the lawlessness in the colony and the unpredictable nature of the system of assignment was well received by committee members, who were already well disposed to the idea of abolition. The committee's recommendations were that transportation should cease as soon as was practicable; that a punishment of hard labour be substituted for transportation; that any gaols established abroad should be built far away from free settlement; that early release of convicts should become more administratively orderly and consistent; and that once they had served their terms, convicts should be encouraged to go back home to enjoy the freedom they had temporarily forfeited.

Reaction to the recommendations of the Molesworth Report was quick. [media]One of Governor Gipps's first administrative tasks when he took up his appointment in 1838 was to prohibit the assignment of convicts for domestic service in towns. They could only be assigned to work in remote areas. The last convicts were assigned in 1841. From 1840 to 1843 the number of assigned convicts shrank from 22,000 to slightly more than 4,000.

The last convict ship

In August 1840, an Order in Council[media] prohibiting transportation to the east coast of Australia became effective. The last convict ship to arrive in Sydney as part of the old transportation system was the Eden, which arrived in late 1840. The idea of convict transportation was not, however, entirely dead. There were further attempts to revive it over the following ten years, but the existence of the system, as such, soon passed into history, and Sydney started to work at erasing the legacy of its penal origins.

The bogeyman of transportation lingered on, heavily promoted by WC Wentworth, among others. The Secretary of State for the Colonies, (later Prime Minister) William Gladstone suggested in a letter to the governor of New South Wales that transportation could be resumed if the Legislative Council so wished. A committee of the Legislative Council, chaired by Wentworth, endorsed the reintroduction of assignment. He and other wealthy landowners wanted the supply of labour for the wool runs to be increased. After all, not many free immigrants wanted to start their new lives in New South Wales as shepherds on remote squatting runs. There was a popular backlash against the proposal, because of the effect this might have on both the price of labour (reduce it) and the crime rate (increase it). Despite the committee's recommendation, the Legislative Council recommended against the resumption of transportation but only by a narrow majority. Although defeated in this instance, the squatting lobby still had political clout throughout the 1840s.

Another round of pressure was put on the Legislative Council two years later, and this time it relented. [media]It agreed to the transportation of 236 'high-class' convicts. The broader population of Sydney greeted the news with a loud and resounding protest. Some colonists were fearful that such an unjust act, so repugnant to the people, might threaten their loyalty to the Crown. [media]Eventually another 1,400 men were received unwillingly by the city and the colony, and the last convicts arrived in New South Wales in 1850.

References

Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: Biography of a City, Random House Australia, Milsons Point NSW, 1999