The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Fallen on the Ultimo Presbyterian Church Roll of Honour

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Fallen of the Ultimo Presbyterian Church Roll of Honour

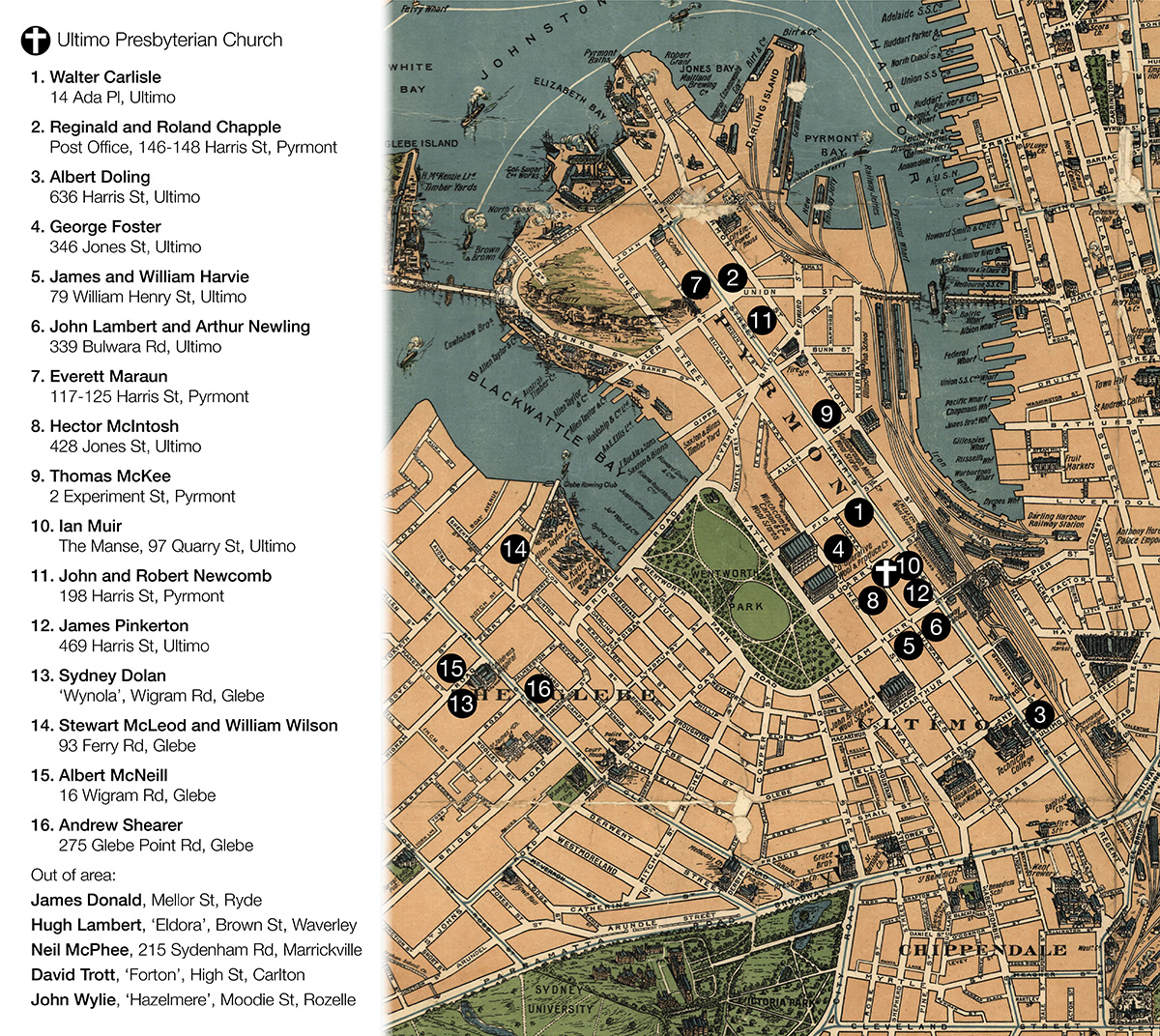

[media]The Ultimo Presbyterian Church Roll of Honour, now located in the Ultimo Community Centre in Harris Street, lists the names of 36 men with associations to the Ultimo community who enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Four of those men never returned. Their war service was recorded and their families marked their grief by advertising their loss in newspapers, writing to the authorities for acknowledgement and donating their mementoes to the Australian War Memorial. Here are their stories.

Killed in action

[media]The oldest Ultimo man to die in the World War I was 32-year-old Stewart Jamieson McLeod, who took part in what has become known as the worst 24 hours in Australian military history, the Battle of Fromelles, on 19 July 1916. [1] He was part of the 5th Division, which suffered 5,533 casualties in one night, with 2,000 of those declared dead or missing. [2] Private McLeod survived this battle only to be killed in action a month later at Fleurbaix on 26 August. [3] Mrs McLeod later donated a French souvenir embroidered handkerchief that her husband had sent to her to the Australian War Memorial collection. [4]

'My boy is dead'

Hobart-born George Albert Foster lived with his parents at 346 Jones Street, just around the corner from the Ultimo Presbyterian Church, when he enlisted in the AIF in March 1916. [5] An ironmoulder by trade, he undertook an apprenticeship for six years at the ironworks James Bonner and Sons Ltd at 17 McKee Street, Ultimo. [6]

Foster's war service was tragically short. After departing Sydney he disembarked at Plymouth in October 1916. He was found absent without leave (AWL) in December before he was sent to the front in Étaples. The fierce fighting of the Second Battle of Bullecourt commenced at 3:45am on 3 May 1917 and it appears Foster was part of the first assault on German lines which was intended to break through the barbed wire. [7] The men of the 5th Brigade, which included Foster's battalion, failed to get through the wire and were cut to pieces by machine gun fire. [8] The Allied Forces advanced the line about one kilometre, at a heavy cost. Foster was one of 7,000 Australian casualties. He was wounded in action on the first day of battle and then received gunshot wounds to his back and right arm. He died of his wounds on 5 May 1917.

Three weeks after his death, Foster's family, friends and neighbours posted tributes in The Sydney Morning Herald Roll of Honour pages:

FOSTER.—Died of wounds received in France, May 5, 1917, George Albert Foster, aged 26 years, dearly loved son of the late George Foster and Amy Foster, 346 Jones-street, Ultimo.

He rose responsive to his country's call

And gave for her his best, his all.

FOSTER.—Died of wounds in France, May 5, 1917,

Private G. A. Foster. He marched away so fearless, his young head proudly held. Inserted by his loving uncle, E. White.

FOSTER.—Died of wounds in France, May 5, George Albert Foster, aged 26 years. A fighter and a unionist. Inserted by his loving cousins, Oscar and Linda Nielsen.

FOSTER.—Killed in action in France, May 5, Private George Albert Foster, dearly loved cousin of Mr. and Mrs. George Whitmore, of King-street, Rockdale, aged 25 years. He died as he lived—honourably.

FOSTER.—Died of wounds received in France, May 5, 1917, G. A. Foster, aged 26 years.

A brave young life which promised well,

By the will of God a hero fell.

Inserted by his sorrowing friend, Elsie.

FOSTER.—Private G. A. Forster, died of wounds in France, May 5, 1917.

Inserted by his sincere friends, Mrs. Anderson and family, 344 Jones-street, Ultimo. [9]

Foster was a man with a wide circle of friends and relatives, and possibly a sweetheart, 'a fighter and a unionist', honourable and loved. The grief did not ease. A year after his death his mother and little brother posted a memorial tribute:

In loving memory of my dear son, Private George A. Foster, 18th Battalion, aged 26 years, died of wounds in France, May 5, 1917.

When he wrote his last fond letter

He was sure of victory.

"When the war is over mother,

I will then come back to thee."

My boy is dead, the cable tells me.

No more his native land he'll see

But when the war is over

Still I dream he'll come to me. [10]

'To manhood days I brought him'

Hector McDonald McIntosh lived with his widowed mother at 428 Jones Street, Ultimo, when he enlisted in the 3rd Battalion at Liverpool in July 1915. [11] He was born in New Zealand but his attestation papers state he was born in Sydney. He was also 17 but claimed he was 18, providing a note from his mother giving him 'full permission to join the soldiers'. [12]

In Cairo in February 1916, McIntosh was hospitalised with venereal disease. He then embarked for Marseilles and joined his unit in Étaples the following month. He was admitted to hospital in Boulogne on 11 June with a gunshot wound to his abdomen and suffering complications from a gas shell. He was classified as 'dangerously ill'. Four days later he was taken off the dangerously ill list but was reported seriously ill again on 9 July and was transferred to England where he died, at Colchester, on 12 July 1916. His service record notes the cause of death was septic bronchitis and pneumothorax – illnesses caused by exposure to gas warfare.

Two days after his death a progress report published in The Sydney Morning Herald noted his condition was 'improving'. [13] The truth reached home a little later. On 24 July 1916 another notice appeared, inserted by McIntosh's mother, brother and sister:

To manhood days I brought him,

And then he heard the call.

To manhood days I brought him,

And then I gave my all. [14]

Two months later, McIntosh's sister also died. In just three years Mrs McIntosh lost a husband, a son and a daughter. [15]

Dead Man's Penny

Pyrmont resident John Alexander Newcomb[media] was also aged 17 when he enlisted in the AIF, arriving in Gallipoli on 20 December 1915. [16] He and his company of men were responsible for holding Courtney's Post before the evacuation of the Peninsula in December 1915. After training in Egypt Newcomb was sent to France in March 1916. His service record notes: 'Took part in a raid on enemy trenches on night of 26–27 June 1916'. Newcomb was one of 79 troops who raided German trenches south east of Bois-Grenier near Armentières, at around midnight. The raid was one of a series conducted by ANZAC troops as part of the Somme Offensive, during which the Germans 'met the advance at the parapet with bombs'. [17]

Newcomb fought in the battle at Poziéres from 25 July 1916. In August he received a 'severe' gunshot wound to his right forearm and spent the remainder of 1916 and early 1917 in convalescent camps in England, returning to his battalion in France in August 1917. He received a severe penetrating gunshot wound to his chest during the aftermath of the Battle of Menin Road in September 1917 and was again evacuated to England. Over the next few months, reports were sent of his recovery until a relapse forced authorities to send Newcomb home to Australia for further treatment.

Newcomb [media]arrived in Sydney in May 1918 and was treated at Randwick Military Hospital. He was formally discharged in November but appears never to have left the hospital. In July 1919 his sister wrote to the authorities asking for something to console their mother:

He was still in hospital at Randwick when he passed away on 12 April of this year. Our mother is very anxious to have some memento to hang on the wall in memory of our darling lad who suffered so much for King and Country? [18]

In the end, military authorities deemed his death was war-related and issued the family with a Next of Kin Plaque, known colloquially as a 'Dead Man's Penny', which was given to the families of those who died on active service or whose deaths could be attributed to the war.

Counting the losses

[media]The four dead on the Ultimo Presbyterian Church Roll of Honour are a reminder of the true cost of war, for the fallen and for their friends, family and community. Perhaps these more localised stories about how the war affected the soldiers, their families and the broader community can counter what Monash University Professor Bruce Scates has termed 'commemoration fatigue' and also the obsessive, jingoistic focus on what happened on the shores of Gallipoli. [19]

Further reading

Australian War Memorial. 'Second Battle of Bullecourt'. Australian War Memorial website. https://www.awm.gov.au/military-event/E73/

Charles EW Bean. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. 11th ed. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1941.

Peter Burness. 'The worst night in Australian military history: Fromelles'. Australian War Memorial Blog: News, 18 July 2008. https://www.awm.gov.au/blog/2008/07/18/the-worst-night-in-australian-military-history-fromelles/

John Donegan. 'Monash chair of History and Australian Studies slams 'spectacle' of World War One commemorations'. ABC News, 11 September 2015. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-09-11/historian-slams-misguided-world-war-one-commemorations/6768172

New Zealand War Graves Project. 'Hector McDonald McIntosh'. New Zealand War Graves Project. http://www.nzwargraves.org.nz/casualties/hector-mcdonald-mcintosh

Yves Le Maner. 'The two battles of Bullecourt (April and May 1917)'. Remembrance Trails - Northern France. http://www.remembrancetrails-northernfrance.com/history/battles/the-two-battles-of-bullecourt-april-and-may-1917.html

Bruce Scates. 'Annual History Lecture 2015 – Anzac Amnesia: How the Centenary Forgot the War'. 8 September 2015. History Council of New South Wales. http://www.historycouncilnsw.org.au/history/post/annual-history-lecture-2015-anzac-amnesia-how-the-centenary-forgot-the-war/

Notes

[1] Peter Burness, 'The worst night in Australian military history: Fromelles,' Australian War Memorial Blog: News, 18 July 2008, https://www.awm.gov.au/blog/2008/07/18/the-worst-night-in-australian-military-history-fromelles/, viewed 20 September 2015

[2] Peter Burness, 'The worst night in Australian military history: Fromelles,' Australian War Memorial Blog: News, 18 July 2008, https://www.awm.gov.au/blog/2008/07/18/the-worst-night-in-australian-military-history-fromelles/, viewed 20 September 2015

[3] National Archives of Australia: B2455, McLeod SJ

[4] Australian War Memorial, 'French souvenir handkerchief: Mrs Marion McLeod,' ID number REL/05593, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/REL/05593/, viewed 20 September 2015

[5] Australia, Birth Index, 1788-1922, Registration no. 1040 and National Archives of Australia: B2455, Foster GA

[6] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Foster GA

[7] 'Second Battle of Bullecourt,' Australian War Memorial https://www.awm.gov.au/military-event/E73/, viewed 20 September 2015; 'Chapter XIII – The Second Battle of Bullecourt (II),' Volume IV - The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917 in Charles EW Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, 11th edn (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1941), 545

[8] Yves Le Maner, 'The two battles of Bullecourt (April and May 1917),' Remembrance Trails - Northern France, http://www.remembrancetrails-northernfrance.com/history/battles/the-two-battles-of-bullecourt-april-and-may-1917.html, viewed 20 September 2015

[9] 'Family Notices,' The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 May 1917, 12, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15709476, viewed 20 September 2015

[10] 'Family Notices,' The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 May 1918, 11, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15777520, viewed 20 September 2015

[11] New Zealand, Birth Index, 1840–1950. Microfiche, Folio no. 1242 and National Archives of Australia: B2455, McIntosh HM

[12] National Archives of Australia: B2455, McIntosh HM

[13] 'New South Wales. Killed In Action,' The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 July 1916, 5, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15698147, viewed 20 September 2015

[14] 'Family Notices,' The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 July 1916, 8, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15702870, viewed 20 September 2015

[15] 'Hector McDonald McIntosh,' New Zealand War Graves Project, http://www.nzwargraves.org.nz/casualties/hector-mcdonald-mcintosh and 'Family Notices,' The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 September 1916, 8, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15699361, viewed 20 September 2015

[16] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Newcomb John Alexander and NSW Births Deaths and Marriages, Registration number 1898/27574

[17] 'Next of kin plaque: Private J A Newcomb, 18 Battalion, AIF,' Australian War Memorial https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/REL39378/, viewed 20 September 2015

[18] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Newcomb John Alexander

[19] John Donegan, 'Monash chair of History and Australian Studies slams 'spectacle' of World War One commemorations,' ABC News, 11 September 2015 http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-09-11/historian-slams-misguided-world-war-one-commemorations/6768172, viewed 20 September 2015

.