The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

War Memorials for World War I

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

War Memorials for World War I

[media]More than 60,000 Australians died in World War I, but only one Australian body, that of Major-General Sir William Throsby Bridges, was brought home from the battlefields. [1] These losses were the source of the war memorial movement. Because the families of the war dead had no graves to visit, it was felt inscribing the name of someone who was buried or lost on the other side of the world, or placing a wreath in their memory, could be an acceptable substitute for visiting a grave. Thus, public memorials for groups of soldiers became the favoured means of recording and remembering the dead and, in many cases, for honouring those who had served and survived.

General Memorials

[media]The principal memorial commemorating all those from New South Wales who served is the Anzac Memorial in Hyde Park, which was dedicated in 1934. [2] Although it was first proposed during the war, delays in its construction led the state government to construct the Cenotaph in Martin Place, opposite the General Post Office colonnade, in 1927. This site had been an important venue during the war for recruiting rallies and other patriotic events and the Cenotaph quickly became the focus for the commemoration of Anzac Day and other military anniversaries. [3] Prior to this the Anzac Parade Obelisk, unveiled in 1917 when Randwick Road was widened and rebuilt as a memorial avenue, was the a major site for such observances, despite being located several kilometres from the city centre. The obelisk was fitted with hooks to hang wreaths. [4]

Hyde Park's Archibald Fountain, a [media]gift to the city in the will of JF Archibald, commemorates Australia and France fighting side by side in World War I 'for the liberties of the world'. [5]

Local Memorials

Large numbers of group memorials commemorated those lost from towns or suburbs, but remembering the dead in all the contexts of their lives also became important. The names of the fallen and returned appeared on memorials where they had worked, attended school, worshipped, and in their sporting or fraternal organisations.

Australia's [media]earliest World War I memorial is probably that unveiled in Balmain in April 1916, while the war still raged. [6] The local council erected it, and four local businessmen paid for the marble tablets that were inscribed with the names of the dead. Six months later the Manly War Memorial was unveiled, the gift of the family of Private Alan Mitchell, the first man from that district to die. [7]

Virtually all World War I memorials were erected by local effort and funding, including private philanthropy and public subscription. [8] Many decisions, some of them contentious, had to be taken. The memorial's location had to be both prominent and accessible, with preference usually given to an important street intersection or a park. Proximity to the local school was the next most frequent choice, so that the youth of the area would be constantly reminded of the sacrifices of earlier generations. Sites adjacent to the town hall or post office were also favoured, as they were likely to be visited regularly by large numbers of people.

Communities also had to decide whether their memorial should be symbolic, utilitarian or a blend of the two. The Balmain memorial was a largely symbolic obelisk but it incorporated a streetlight and four drinking fountains (later decommissioned). Some symbolic memorials included a clock. In most places people voted for monumentality over utility but a minority of communities voted for a memorial which would be of practical use. These included playing fields with memorial gates, community halls, hospitals or wards. Some communities preferred a living memorial, such as a grove or avenue of trees.

Design elements of memorials

[media]Arguments erupted about aesthetics and design. Some of the early memorials were designed and sculpted by local tradesmen, with the no-doubt laudable intention to involve locals in the design and construction processes, but they were not always artistically successful. A cement soldier, derided as a 'grotesque figure' and later removed in mysterious circumstances, surmounted the memorial at Miranda. [9] In 1919 the state government appointed a Public Monuments Advisory Board to approve the site and design of any war memorials to be erected in a public place. It issued a booklet of advice on war memorial design, which featured Miranda as an example of what to avoid. Memorials were to be in good taste, dignified, and of the highest artistic merit. [10]

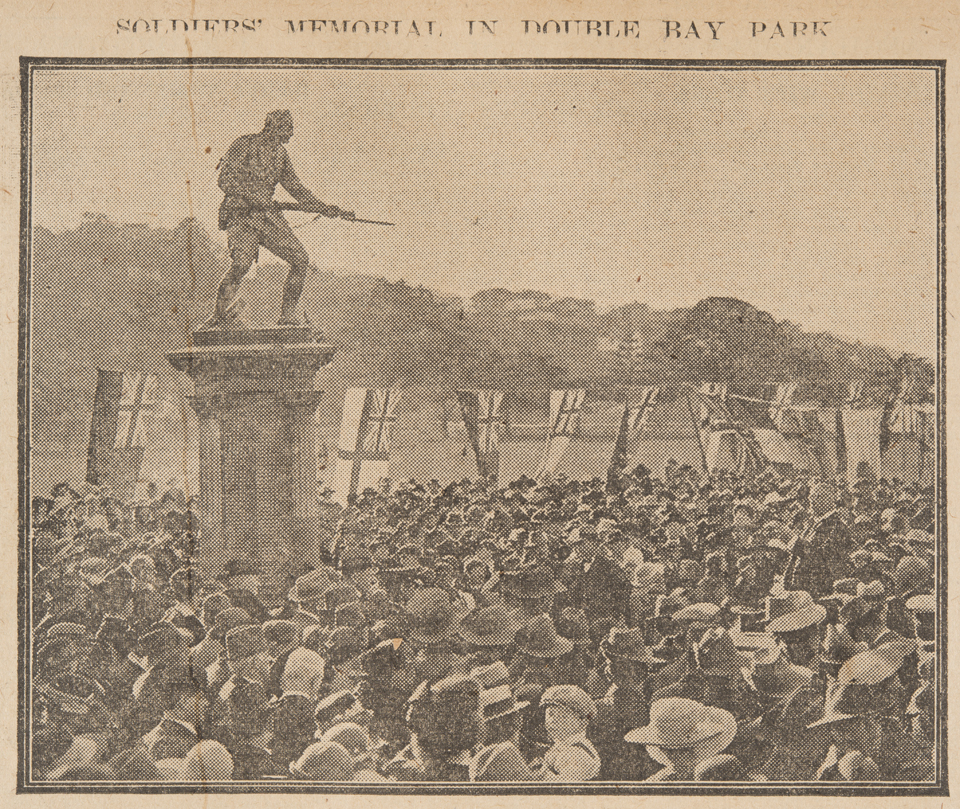

[media]A soldier on a pedestal was a popular choice, and stonemasons and sculptors quickly sensed a market. They offered many variations in uniform and attitude to communities seeking such an image. In most examples the soldier stands, with his rifle, either proudly at attention or quietly with bowed head, but the soldier on the Double Bay memorial is in fighting stance. [media]Sculpture authority Michael Hedger has said 'This aggressive work, emphasising the threatening bayonet, is in stark contrast to most memorials where moods of peace and sacrifice are invoked, and historian Ken Inglis has said this is 'the most belligerent of all Great War figures.' [11]

[media]The female 'Winged Victory' image was also popular, the most spectacular example being that sculpted by Gilbert Doble for the Marrickville War Memorial. A carved base supports a granite Corinthian column, on top of which he placed a four-metre high bronze angel holding both a wreath and a sword. It was the largest known bronze sculpture on any Australian memorial. [12] Owing to structural issues, it was removed from display between 1962 and 1988, and then again in 2008. In 2014, lacking the resources to undertake necessary restoration, Marrickville Council decided to transfer ownership of the iconic sculpture to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. There it will be conserved, and feature in the First World War Galleries. A new Winged Victory sculpture is to be commissioned for Marrickville. [13]

[media]Doble sculpted two other female figures for memorials in Sydney, at Leichhardt and at Pyrmont, that remain in situ. [14]

Guns as memorials

[media]Some World War I memorials incorporate captured enemy guns. The Commonwealth Government distributed more than 5,000 of these trophies to suburbs and towns throughout Australia. The first gun captured, and the first to be turned into a memorial, was a gun from the German raider Emden, captured by HMAS Sydney in 1914 and placed at the southeastern corner of Hyde Park in Sydney. [15] Two other artefacts of the Sydney's victory are a portion of its bow, which is now embedded in the sea wall at Milsons Point, and its mast, which stands at Bradleys Head. [16]

The trophy distribution scheme led to many disputes. Some communities felt slighted when they were offered a small gun and asked for more or larger weapons so as to better reflect their contribution to the war effort. Other communities refused to accept their allocation on the grounds that they would not display objects that had been used to kill Australians. Over time some of these trophies have disappeared without trace, often when their parent memorial was being moved or refurbished. [17]

Protocols

Problems also arose in securing a suitable person to perform the unveiling ceremony. The Governor-General was in heavy demand, the state governor a close second, and senior military figures or members of parliament were called upon if vice-regal patronage could not be secured. The involvement of clergy in the dedication of a civic memorial presented a dilemma; because the fallen were of many faiths, or none, a secular ceremony was usually preferred. [18]

Unveilings were always attended by large numbers of local people and returned soldiers and bereaved families were given places of honour. One sorry exception was the Katoomba Anzac Memorial Hospital, whose committee, having installed an Honour Roll in the foyer, took advantage of the 1927 motoring tour of the Blue Mountains by the Duke and Duchess of York. Contriving an unscheduled stop for the royal car outside the hospital, the committee invited their Royal Highnesses in and asked the Duchess to unveil the Honour Roll, which she did, in the presence of the committee members and their wives. The subsequent outrage from local returned soldiers and bereaved families, who had not been told of these arrangements and were not present, erupted in the press and resulted in an angry public meeting and a letter of protest to the Duke. A judicial inquiry was held which found that although the committee's action was 'ill-conceived and unfortunate' it did not, as the protesters had claimed, amount to 'a gross insult to the relatives of the soldiers'. [19]

The gathering of the names to be listed on a memorial was a challenging process. Civic memorials were organised by local committees who did not always have access to reliable lists of local servicemen or the casualties among them. The first decision to make was whether the proposed memorial should list only those who paid the supreme sacrifice or honour all who had been patriotic enough to volunteer. Those who served and survived considered that their patriotism deserved to be recognised but others argued that the only purpose of a memorial was to honour the deceased. In some places men who had volunteered but who had been rejected for medical or other reasons argued, mostly unsuccessfully, that they should also be listed, on the grounds that they were just as patriotic as those whose enlistment had been accepted. [20]

Once the question of whose names to include was resolved, the task of collecting the names began. Advertisements in local newspapers invited returned servicemen and the families of those who had died to submit their names. But not everyone read the local paper, so clergymen were often asked to spread the word and local sporting or social or fraternal organisations were consulted. Despite every effort, large numbers of memorials had names added after their completion. [21]

As well as local civic memorials, memorials were created to honour those who served or those who died in other settings. Government departments and large employers, sporting clubs, Masonic lodges, schools and churches all created honour rolls, or designated objects like fences, gates, halls and drinking fountains as memorials to service. One prominent memorial of this type, passed every day by thousands of motorists and others who probably have no idea of its intention, is the Cricketers' Memorial drinking fountain at the intersection of Cleveland and South Dowling Streets, erected by the Moore Park Cricket Association in memory of 33 fallen comrades. [22]

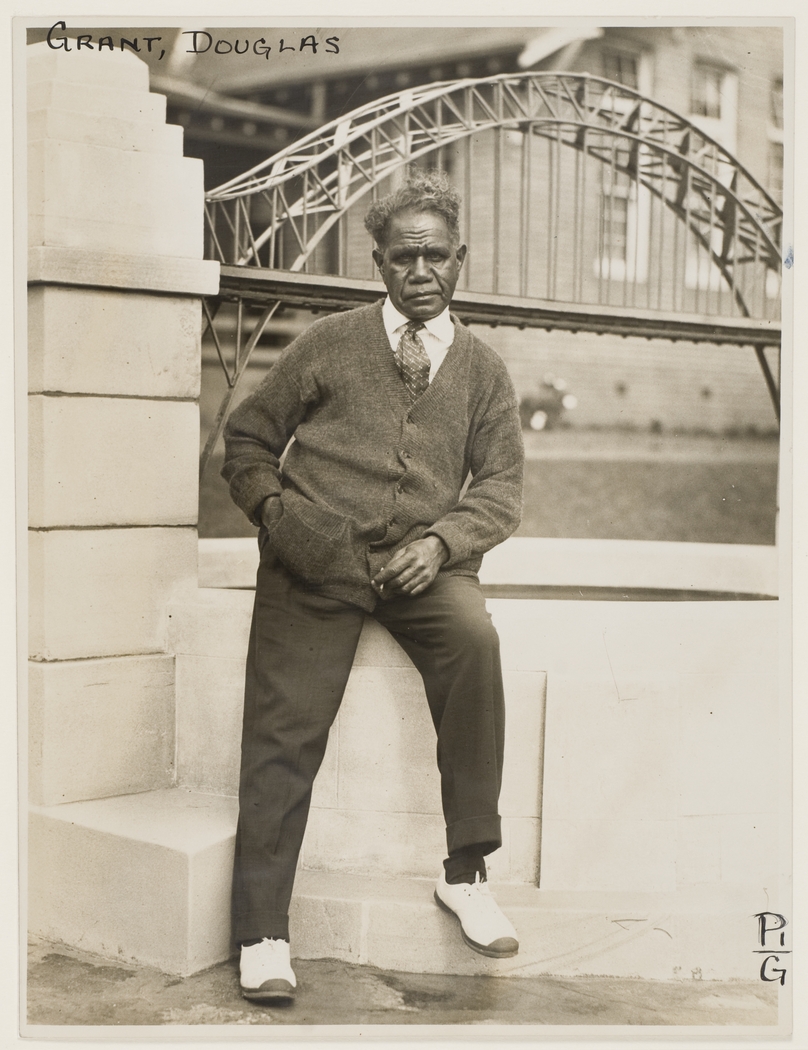

[media]The Callan Park Mental Hospital at Rozelle became home to many returned soldiers suffering from mental breakdowns as a result of their war experience. Douglas Grant, a returned soldier working as a clerk at the hospital, designed and, with hospital residents constructed, a scale model of the new Sydney Harbour Bridge, above a circular wishing well 'in proud memory of those who made the great sacrifice'. The New South Wales Governor unveiled it in 1931, seven months before he opened the real bridge. [23] Private WT Shirley, a returned soldier being treated at the Lady Davidson Convalescent Hospital in North Turramurra, noticed in nearby bushland of the Ku-Ring-Gai Chase a rock that resembled the Sphinx in Egypt. From 1925 to 1926 he carved it into a replica on a scale of about 1:8, dedicating it 'to my glorious comrades of the AIF'. [24]

The University of Sydney commemorated the 197 staff, graduates and students who died in the Great War by means of bronze panels under the central tower entrance to the main quadrangle, and by a 54-bell carillon in the tower which is played at graduations and on other ceremonial occasions and at regular public recitals. The female students of Sydney Teachers College embroidered linen panels with the names of fellow (male) students who had enlisted and these were displayed in the college library. This embroidered memorial is quite probably the only surviving one of its type in Australia. [25]

The Anzac Bridge between Rozelle and Pyrmont, the longest cable-stayed bridge in Australia, is a memorial to Australians and New Zealanders who served in World War I. Bronze statues of an Australian and a New Zealand soldier guard it, and the flags of both countries fly from its pylons.

The memorialisation of women

War memorials generally honour fighting men, so the contribution of Australian women to the 1914-18 war effort has been only sparingly acknowledged, although around 2,300 women of the Australian Army Nursing Service served in World War I. Of these, 21 women died of illness, but few local memorials record their names. For example, of about 30 nurses from Mosman who served, only nine are listed on the Mosman War Memorial. [26] Sydney Hospital has an Honour Board that includes 20 of its nurses who served in that war, as well as one listing World War II nurses. [27]

When men volunteered for military service their places in offices, factories and farms were often taken by women. Their contribution is acknowledged in the vestibule of the Sydney Town Hall, where a tablet sits as 'A token of gratitude to our women war workers from the returned sailors and soldiers of New South Wales.' [28]

In 1915 a Centre for Soldiers' Wives and Mothers was established in Sydney to provide emotional and material support for women left behind or bereaved by war. In 1922 the Centre erected a memorial drinking fountain facing the wharf at Woolloomooloo, where husbands and sons had 'passed through the gates opposite' to board their troopships. [media]These gates had already become a de facto site of pilgrimage and remembrance for soldiers' wives and mothers, and for several decades, on Anzac Day and other anniversaries, mothers, wives and widows would gather at this memorial to remember and commemorate their sons and husbands. Inglis writes that Miles Franklin, 'a glum observer' of this annual service, described the attendees as 'battered and ageing women present decorated with rosemary (for remembrance) who wept anew at the thin platitudes gargled by the parsons.' [29]

The horses of the Australian Light Horse

[media]The Australian Light Horse took approximately 140,000 Australian horses to the Desert Campaign in Palestine, and the only horse to return was Bridges' mount Sandy. The horses that did not return are honoured by the Horses of the Desert Mounted Corps Memorial at the southwest boundary of the Royal Botanic Gardens, opposite the Mitchell wing of the State Library. [30] The Light Horse is also honoured in the Royal NSW Lancers' Memorial Museum, Parramatta, and in several suburban commemorative plaques and structures, for example Light Horse Park, Liverpool and the Light Horse Memorial Wall, Campbelltown. [31] The Light Horse Interchange of the M4 and M7 contains a 55-metre illuminated mast and 2,000 red batons on the road approaches, to commemorate members of the Brigades. [32] 'Last Farewell', at Holsworthy, is a life-sized statue of a rider farewelling his horse, designed to capture the emotional connection between rider and horse when the riders were informed that their horses would not be returning to Australia with them. [33]

Preserving memorials

Memorials are generally regarded as sacred objects of pride and local identity, deserving of respect. They honour those who died while serving in their country's armed forces. But they have sometimes been mistaken for monuments that glorify war and have thus become the focus for anti-war protests. In particular, the conflicting feelings evoked during Australia's military involvement in Vietnam led to some memorials being vandalised by anti-war protesters, including even the Anzac Memorial in Hyde Park. Some others were vandalised or painted with protest slogans. Other forms of vandalism, without apparent political motive, have damaged other memorials over the years. The Glebe War Memorial suffered several senseless attacks in the 1980s and was restored through the initiative of a small community group and fundraising by the Glebe Society. Not far away, the soldier on the Camperdown memorial, who holds a rifle in the photograph in the War Memorials Register, has since been disarmed.

Australia's war memorials generally, most of them erected during the 1920s, are ageing and must depend on local care if they are to be protected for future generations, though it must be realised that future generations might be less interested in them as time passes. The elements have caused the deterioration of many outdoor memorials and both they and some indoor ones have suffered from neglect or lack of appropriate conservation. The embroidered Roll of Honour at the former Sydney Teachers' College, perhaps unique in its format, presents a particular challenge. After almost a century on display its blue silk embroidery is badly faded and in need of expert conservation if it is to survive.

Memorials have sometimes had to be adapted to changing circumstances. Some, placed in a prominent position such as a major intersection, have had to be moved either for their own safety or for the convenience of traffic flows. From time to time suggestions were made that the Cenotaph be moved from Martin Place because it was obstructing traffic, a problem only solved when Martin Place became a pedestrian plaza in 1968.

The World War I Soldiers' Wives and Mothers Memorial at Woolloomooloo was moved across the street in 1988 when it was in the way of a proposed car park for naval staff. The memorial is now located at approximately the place where the wharf gates were, through which the women caught the last glimpse of their menfolk as they marched onto their ships. [34] The move made a nonsense of the memorial's inscription referring to their loved ones having 'passed through the gates opposite' but perhaps this memorial had served its purpose. For several decades it was a focal point of remembrance and solace for the widows and mothers who assembled there each Anzac Day, but as the number of surviving widows and mothers diminished so did the monument's significance. Their soldier husbands and sons are remembered and honoured elsewhere.

Some memorials have disappeared. With the passage of time the memorial origins of some of the 'utilitarian' memorials such as community halls, libraries, and sporting facilities have been de-emphasised by shortening the name for convenience (the oval, the library, etc) and the facility survives as an amenity whose commemorative character is no longer recognised. Mosman's impressive Anzac Memorial Hall has had a varied history as, among other things, a dance hall and a cinema, and is now a clothing shop. Memorial avenues or groves of trees have been endangered both by the mortality of the trees and the need to widen the roadway. During the second half of the twentieth century many Masonic lodges closed and local government amalgamations made some town halls redundant. Their buildings demolished or repurposed, the memorials or honour rolls in them lost their context and in some cases these objects, once venerated, have vanished. Alternatively they were passed to other authorities such as local councils or local history societies for preservation but these have often not known what to do with them and they have been placed in storage without proper conservation care. Just one example of many such orphans is the World War I Honor Roll apparently from a defunct local Presbyterian church now languishing in the Ultimo Community Centre; its photograph in the official War Memorials Register shows it on the floor propped up against a cupboard. [35] More fortunate are the World War I memorial gates in Darlington. The local town hall was demolished in the 1960s as the University of Sydney expanded into this small working class suburb but the memorial remains and is now in the care of the University.

Many war memorials proclaim Kipling's words 'lest we forget' or Binyon's vow 'we will remember them', or Ecclesiastics 44:14 'their name liveth for evermore'. [36] However, with the passage of time, many memorials will need help to ensure that these promises are kept. The New South Wales Government has established a Community War Memorials Fund to help protect and restore war memorials across the state. [37] The Department of Public Works has published Caring for our War Memorials, a guide for tradespeople and those responsible for the upkeep of memorials. [38] Hopefully, with initiatives like these we will indeed continue to remember them.

References

Michael Hedger. Public Sculpture in Australia. Roseville East: Craftsman House, 1995.

KS Inglis. Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008. First published 1998.

Tom Spencer. Soldier-Teacher War Memorials, Sydney: NSW Department of Education and Training, 2001.

'Conflict', Monument Australia, http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/conflict

New South Wales Government. Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/

Notes

[1] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008)

[2] 'History,' Anzac Memorial Hyde Park Sydney, viewed 28 November 2014, http://www.anzacmemorial.nsw.gov.au/history/

[3] 'Cenotaph - Martin Place Sydney,' Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, viewed 28 November 2014, https://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/cenotaph-martin-place-sydney

[4] Anzac Parade Obelisk, Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, viewed 28 November 2014, http://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/anzac-parade-obelisk

[5] Robyn Tranter, 'Archibald Fountain,' Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, viewed 28 November 2014, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/archibald_fountain

[6] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 103-104

[7] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 106-107

[8] Australian Encyclopaedia, 6th ed., 1996, 8: 3035

[9] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 144-145

[10] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 143-144

[11] Michael Hedger, Public Sculpture in Australia, Craftsman House, 1995, 28; KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 159

[12] Sydney Mail, 5 February 1919; 'Marrickville War Memorial,' Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, viewed 26 November 2014, https://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/marrickville-war-memorial.

[13] Marrickville Council, 'Winged Victory to go to Australian War Memorial,' viewed 1 December 2014, http://www.marrickville.nsw.gov.au/en/council/newsandnotices/mediareleases/21-november-winged-victory-to-go-to-australian-war-memorial/Media Releases; Marrickville Council, 'New Winged Victory statue,' viewed 1 December 2014, http://www.marrickville.nsw.gov.au/en/council/newsandnotices/mediareleases/new-winged-victory-statue/

[14] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 141

[15] 'Destruction of the German Raider "Emden",' Monument Australia, viewed 28 November 2014, http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/conflict/ww1/display/23169-destruction-of-the-german-raider-emden

[16] 'HMAS Sydney 1 Memorial - Milson's Point,' Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, viewed 28 November 2014, http://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/hmas-sydney-1-memorial-milsons-point; 'HMAS Sydney I Memorial Mast,' Monument Australia, viewed 28 November 2014, http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/conflict/multiple/display/94736-h.m.a.s.-sydney-i-memorial-mast

[17] '19 September 2014: Sydney’s War Trophies,' Scratching Sydney's Surface, viewed 28 November 2014, https://scratchingsydneyssurface.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/19-sept-2014-sydneys-war-trophies/

[18] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 436-437

[19] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 192-193; Evening News, 29 April 1927, 30 April 1927, 15 June 1927.

[20] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008). 112-113; 76-177

[21] On the procedures and problems of compiling lists of names see, for example, Angela Phippen, The War Memorials of St Peters Municipality Sydney, New South Wales (incorporating the suburbs of St Peters, Sydenham, Tempe), (Marrickville, Marrickville Heritage Society Inc., 2002)

[22] 'Cricketers Memorial,' Monument Australia, viewed 28 November 2014, http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/conflict/ww1/display/22168-cricketers-memorial

[23] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 233; 'Callan Park (Rozelle Hospital) War Memorial,' Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, http://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/callan-park-rozelle-hospital-war-memorial

[24] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 233; 'Sphinx Memorial - Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park,' Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, viewed 26 November 2014, http://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/sphinx-memorial-ku-ring-gai-chase-national-park

[25] Tom Spencer, Soldier-Teacher War Memorials (Sydney: NSW Department of Education & Training, 2001), 52-53

[26] 'Mosman Nurses at War,' Doing Our Bit, Mosman 1914-1918, viewed 28 November 2014, http://mosman1914-1918.net/project/blog/mosman-nurses-at-war

[27] 'Sydney Hospital World War 1 Roll of Honor,' Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, viewed 1 December 2014, http://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/sydney-hospital-world-war-1-roll-honor; 'Sydney Hospital World War 2 Roll of Honor,' Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, viewed 1 December 2014, http://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/sydney-hospital-world-war-1-roll-honorhttp://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/sydney-hospital-world-war-2-honour-board

[28] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 126

[29] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd ed., (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 218

[30] 'Horses of the Desert Mounted Corps Memorial,' Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, viewed 26 November 2014, https://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/horses-desert-mounted-corps-memorial

[31] 'Australian Light Horse Memorial,' Monument Australia, viewed 1 December 2014, 'Light Horse Memorial Wall,' Monument Australia, viewed 1 December 2014, http://monumentaustralia.org.au//search/display/20681-light-horse-memorial-wall

[32] 'Light Horse Interchange,' Monument Australia, viewed 1 December 2014, http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/conflict/multiple/display/90207-light-horse-interchange/

[33] 'Last Farewell,' Monument Australia, viewed 1 December 2014, http://monumentaustralia.org.au//search/display/21588-last-farewell

[34] 'Woolloomooloo Bay Mothers and Wives Memorial to Soldiers,' Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, viewed 26 November 2014, https://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/woolloomooloo-bay-mothers-and-wives-memorial-soldiers

[35] 'Ultimo Community Centre World War 1 Honour Roll,' Register of War Memorials in New South Wales, viewed 26 November 2014, http://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/content/ultimo-community-centre-world-war-1-honour-roll

[36] Rudyard Kipling, Recessional (1897); Laurence Binyon, For the Fallen (1914)

[37] New South Wales Government, Community War Memorials Fund, viewed 26 November 2014, http://veterans.nsw.gov.au/community-war-memorials-fund/

[38] New South Wales Government, Department of Public Works, Caring for our War Memorials (Sydney: Department of Public Works, 2013), viewed 26 November 2014, http://www.publicworks.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/pdf/Caring%20for%20our%20War%20Memorials.pdf; New South Wales Government, Department of Public Works, Minister's Stonework Program, viewed 26 November 2014, http://publicworks.nsw.gov.au/architecture-heritage/ministers-stonework

.