The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Yemmerrawanne

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Yemmerrawanne

[media]The first mention of Yemmerrawanne in European records is in October 1790, when Captain Watkin Tench wrote about the peaceful 'coming-in' of the Eora to the English Settlement at Sydney Cove. Tench said 'Imeerawanyee', or Yemmerrawanne, was a 'slender, fine-looking youth' and a 'good tempered lively lad' who soon became 'a great favourite with us, and almost constantly lived at the governor's house.' [1]

Two years later, on 10 December 1792, Yemmerrawanne left his homeland on the banks of the Parramatta River to sail 10,000 miles to England with Governor Arthur Phillip and his Wangal kinsman Woollarawarre Bennelong, arriving at Falmouth in Cornwall on 19 May 1793.

He never returned. After a long illness, Yemmerrawanne died from a lung infection on 18 May 1794 at the home of Mr Edward Kent at South End, Eltham in the county of Kent. He was buried in the village churchyard of St John the Baptist, now part of the Royal Borough of Greenwich, southeast of London. He was only nineteen.

Naming Yemmerrawanne

Tench wrote his name as Imeerawanyee, Judge Advocate David Collins called him Yem-mer-ra-wan-nie, and Elizabeth Macarthur called him Imerewanga. His full name 'Yem-mer-ra-wan-ne – Ta-bong-en – Tan-ni' was recorded in a vocabulary kept by Governor Phillip and his aides. [2] Phillip used the spelling Yemmerawanya in letters written in England after 1793.

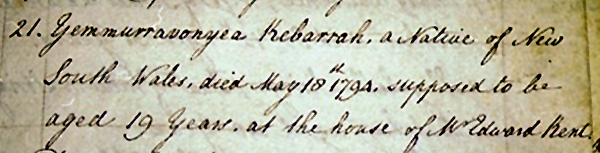

[media]The vicar of Eltham, the Reverend John Kenward Shaw Brooke MA, who conducted a Christian burial service for the Eora man, recorded his death in the Parish register on 21 May 1794, and added a significant detail.

Yemmurrvonyea Kebarrah, a Native of New

South Wales, died May 18th 1794, supposed to be

aged 19 Years, at the house of Mr Edward Kent. [3]

Kebbarah means an initiated man whose upper right front tooth had been knocked out by a stone (from keba, a stone or rock). [4] Only Bennelong and Phillip, who would have attended the funeral at Eltham, could have told Shaw Brooke that Yemmerrawanne was entitled to use that name.

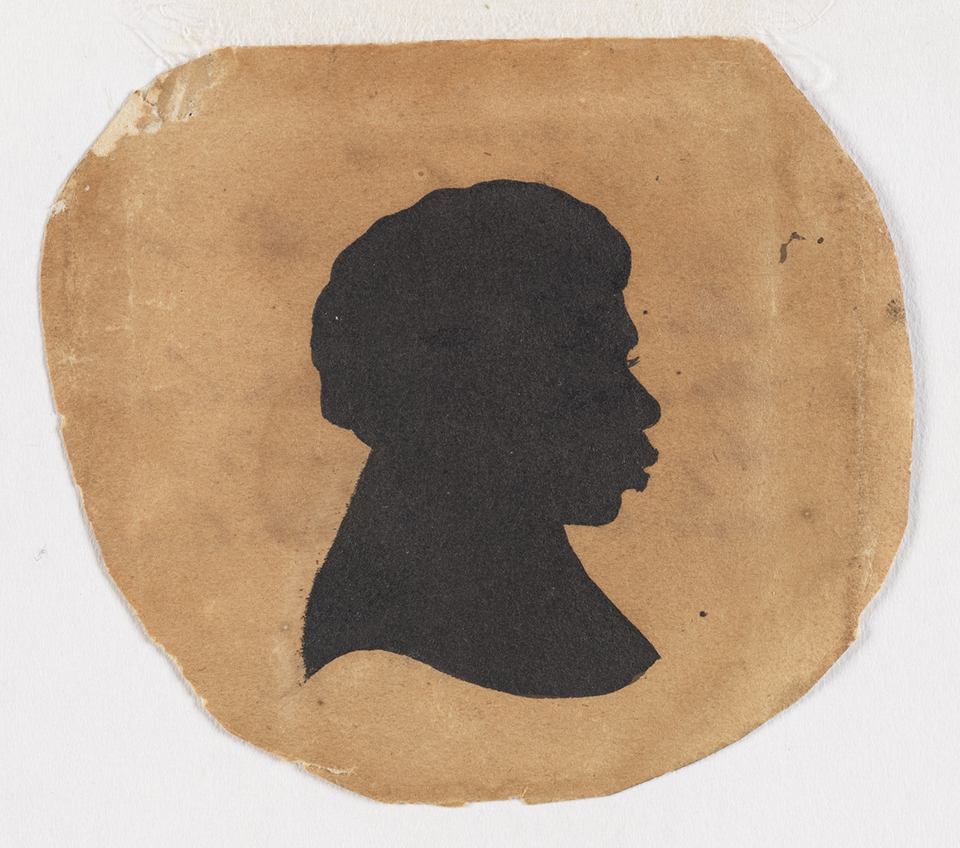

The only known likeness of Yemmerrawanne is a silhouette profile in the Sir William Dixson collection of the State Library of New South Wales. A handwritten inscription on the reverse wrongly states: 'Yuremany, one of the first natives brought from New South Wales by Governor Hunter and Captain Waterhouse.’ [5] It was Governor Phillip who took Yemmerrawanne and his Wangal kinsman Woollarawarre Bennelong from Sydney to England in December 1792 aboard the convict transport ship Atlantic.

Yemmerrawanne and the English in Sydney

Tench, Surgeon John White and John Palmer, with the Aboriginal children Nanbarry and Boorong, met Bennelong at his camp at Kirribilli on 15 September 1790. The English officers suggested he should 'provide a husband' for Boorong, someone who could come and go from the English settlement as he chose. They tried to promote a romance between Yemmerrawanne and Boorong, who then lived with Chaplain Richard Johnson and his wife Mary.

The lad, on being invited, came immediately up to her, and offered many blandishments, which proved that he had assumed the toga virilis [garment of manhood]. But Abaroo disclaimed his advances, repeating the name of another person, who we knew was her favourite. The young lover was not, however, easily repulsed, but renewed his suit, on our return in the afternoon, with such warmth of solicitation, as to cause an evident alteration in the sentiments of the lady. [6]

Boorong's favourite, the other person she named, was probably Carradah, a Gamaragal (Cameragal) from the Manly area who already had a wife.

Bennelong complained to the English officers that 'he and his countrymen' had been robbed of fishing spears and other implements. When Tench crossed the harbour again the next day to return the stolen weapons Yemmerrawanne claimed a 'wooden sword' (fighting club). Showing off to Boorong, he attacked a grass tree (Xanthorrhea species) with the weapon, shouting, gesturing and calling on everyone to look at him. Tench wrote

Having conquered his enemy, he laid aside his fighting face, and joined us with a countenance which carried in it every mark of youth and good nature.

After this performance Yemmerrawanne completely ignored Boorong. Though too young to grow a beard, he was delighted to have his hair clipped and combed. [7]

Initiation

Early in February 1791 Yemmerrawanne, then aged about sixteen, was initiated at a gathering in a bay in Gamaragal territory on the north shore of Sydney Harbour with another youth who had been staying with Governor Phillip (probably Boorong's brother Ballooderry). Bennelong officiated in this ceremony, knocking out teeth with a specially cut womera (throwing stick) and raising scars on the skin of initiates. He might also have acted as Yemmerrawanne's sponsor.

The new-made men returned to Sydney Cove crowned with split rushes, with reed bands bound around their upper arms and a broad streak painted on their chests. Their front upper incisor teeth had been knocked out and Yemmerrawanne had lost a piece of his jawbone. Despite the ordeal they were proud of their new status and bore the pain defiantly.

I have seen a considerable degree of swelling and inflammation; following the extraction, Imeerawanyee, I remember, suffered severely. But he boasted the firmness and hardihood, with which he had endured it. It is seldom performed on those who are under sixteen years old. [8]

The Governor's house

Clothes were specially made for Yemmerrawanne and he was taught to wait at table. As an initiated man he refused to take instructions from the cheeky, uninitiated Nanbarry, as Tench relates in an anecdote about one occasion, in November 1790, when Mrs. Elizabeth Macarthur (wife of John Macarthur) dined at Governor Phillip's house.

This latter [Nanbarry], anxious that his countryman should appear to advantage in his new office, gave him many instructions, strictly charging him, among other things, to take away the lady's plate, whenever she should cross her knife and fork, and to give her a clean one. This Imeerawanyee executed, not only to Mrs. M'Arthur, but to several of the other guests. At last Nanbaree crossed his knife and fork with great gravity, casting a glance at the other, who looked for a moment with cool indifference at what he had done, and then turned his head another way. Stung at this supercilious treatment, he called in rage, to know why he was not attended to, as well as the rest of the company. But Imeerawanyee only laughed; nor could all the anger and reproaches of the other prevail upon him to do for one of his countrymen, which he cheerfully continued to perform to every other person. [9]

Marines fired their muskets at two of Bennelong's allies, Bigon and Bangai, who were robbing a potato garden at Tarra (Dawes Point) on 29 December 1790. Four days later Yemmerrawanne led Surgeon John White, Nanbarry and an Aboriginal woman to a nearby bay where they found Bangai's body. He had bled to death after a musket ball passed through his shoulder. [10]

The voyage to London

On 10 December 1792 Yemmerrawanne and Bennelong embarked from Warrane (Sydney Cove) on the convict transport ship Atlantic with Governor Arthur Phillip who was returning to England. On 21 May 1793, their first day in London, they were measured for ruffled shirts, waistcoats, breeches, frock coats with plated buttons and buckled shoes suitable for wearing in society.

On 28 May 1793 both the London Packet and the General Evening Post reported: 'Governor Phillip has brought home with him two of the natives of New Holland, a man and a boy, and brought them to town.' The English press had formed an impression of Yemmerrawanne as a youth who seemed to live in Bennelong's shadow. [11]

They lodged in Mayfair at the home of William Waterhouse, father of Lieutenant Henry Waterhouse, who broke the spear that wounded Governor Phillip at Manly Cove in September 1790.

Clad in their new finery Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne sat in a private box with Governor Phillip at the King's Theatre at the Haymarket to see the Italian comic opera Gli zingari in Fiera ('Gypsies at the Fair') on Saturday 8 June 1793. It was their first experience of English theatre. Following the Opera they watched Madame Janet Hiligsberg, wearing fetching tights, dance a 'pastoral ballet' Le Jaloux Puni ('The Jealous Punished'). [12]

Yemmerrawanne, like Bennelong, must have marvelled at the London sights. The two Wangal men swam in the Serpentine in Hyde Park and saw the illuminations in St. James's Street on 3 June, eve of the King's birthday.

Not long after their arrival in London 'Benelong, and Yam-roweny, the two Chiefs … from Botany Bay' brought their own music to Waterhouse's home, beating sticks and singing in their own language. The words and music of this 'Song of the Natives of New South Wales' were written down by Waterhouse's neighbour Edward Jones, a Welsh harpist and bard to the Prince of Wales (later George IV), who published the score in his Musical Curiosities in 1811. This was certainly the first time an Aboriginal song was performed in Europe and the printed score is the oldest known published music from Australia. [13]

Illness and death

On 29 September 1793 the London Observer reported that Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne both seemed ill and needed walking sticks to get around the Mount Street area, adding that 'one of them appears much emaciated'. This was Yemmerrawanne, who was beginning to feel the effects of a lung ailment. The Scots naturalist Robert Jameson, who saw them at Parkinson's Museum on 8 October, wrote 'One of them [Yemmerrawanne] appears much emaciated … they seem constantly dejected, and every effort to make them laugh has for many months past been ineffectual'. [14]

Yemmerrawanne somehow injured his leg the following month, further aggravating his illness. On 15 October a coach took the Aboriginal men to the house of Mr. Edward Kent in Eltham, where Dr. Gilbert Blane, a former navy surgeon and physician to the Prince of Wales, treated Yemmerrawanne. The house was owned by Governor Phillips's patron Lord Sydney, whose country seat, Frognal House, was at nearby Chislehurst.

Despite repeated doses of laxative mixes, bark decoctions, embrocations (liniment), anodyne draughts (painkillers, possibly opium) and blister dressings (hot plasters) dispensed by apothecary George John Vivers, poor Yemmerrawanne's health continued to decline. On 30 November Dr. Blane was called to see him at Eltham and was paid three guineas, while the apothecary's bill for medicines was four guineas. A further account for £1.3.1 emphasises how badly Yemmerrawanne was suffering: 'Two Beds, coverings and furniture (all rendered totally useless) and extra attendance Fires and lights during Yemmerawanya's sickness.' In December 1793 Dr. Blane claimed £4.14.6 for 'Attendance, bleeding, dressings for Yemmerrawanne'.

Winter set in and on 30 January 1794 Waterhouse purchased a warm blue greatcoat for Yemmerrawanne and a 'Jacket for Mr. Bennalong' from Jonathan West, a Pall Mall tailor, at a cost of £1.5.0.

Yemmerrawanne, now being dosed with Dr. Fothergill's pills at five shillings per box, somehow managed to find the strength to visit the Houses of Parliament at Westminster with Bennelong on Wednesday 16 April 1794.

John Briggs cared for the two Aboriginal men in Kent's house for more than three months during 1794 but was not paid for this service. 'I did everything for them in my power', he claimed in a letter to Phillip on 17 October 1794, months after Yemmerrawanne's death, asking for payment for 'the attention I have paid, and the time I have given up to the Natives'. Briggs, who seems to have been a Quaker, said he could not pay board and lodging 'while staying at my Brother's house' but instead had been 'an expence to my friends'.

Phillip wrote to Charles Long, Secretary to the Treasury, from Millbrook, near Southampton, on 20 October 1794 enclosing Briggs's claim. Phillip wrote

I know the greatest care and attention was paid to them, & particularly to Yemmerawanya, who during his illness required more than one person to attend him.

Soon afterwards Briggs received a payment of nineteen guineas. Briggs had also given reading and writing lessons to both Aboriginal visitors, although his claim for £1.9.0 for that service was crossed out on the account sent to the Treasury.

Yemmerrawanne's death was reported in the Morning Post (29 May 1794) and other London newspapers. 'One of the two natives of Botany Bay, who came over with Governor Phillip, is dead: his Companion pines much for his loss.' [15]

An empty grave

[media]Bills in the Treasury Board Papers at The National Archives in Kew indicate that Yemmerrawanne's grave was covered with turf by a gravedigger, who charged one shilling and sixpence for his services. The granite headstone cost £6.16.0. [16] The inscription reads:

In Memory of

YEMMERAWANYEA

a Native of

NEW SOUTH WALES

who died the 18th of May, 1794

In the 19th Year of his

AGE [17]

Today Yemmerrawanne's tombstone has been restored, but rests against a wall facing Well Hall Road, Eltham's High Street. Margaret Taylor, an archivist at Eltham Parish Church, stated in 1991 that it had been moved several times and that an elderly resident had told her it once stood on the other side of the path. [18] Until recently it was believed that Yemmerrawanne's gravestone had been separated from his burial plot after German bombs rained on Eltham during World War II.

There is another version of why the location of the grave is unknown. Seeking to exhume Yemmerrawanne's remains, Geoffrey Robertson QC discovered, as he told television journalist Liam Bartlett, that 'when the space was needed they just threw his remains out…he was disposed of'. [19] The Australian-born barrister and human rights lawyer later named his source as the Bishop of South London. [20]

Robertson retold the story in Dreaming too Loud.

It seemed a simple matter to uplift Yemmerrawannie, whose headstone stood in Eltham. But then, to his almighty embarrassment, the bishop discovered that the grave was empty: the plot had been needed for more important white parishioners and the Aborigine's bones had been thrown away.

Of course, the bishop confided, if it was bones we wanted, there were some lying around...I resisted the temptation. [21]

Three Aboriginal men, Michael Bungapidju and Murphy Dhulparippa from Yirrkala in the Gove Peninsula, Arnhem Land, and Ralph Nichols from Melbourne, made a pilgrimage to the grave of 'Yemmerawanyea' at Eltham in March 1982 but were not aware that his body had been removed. [22] Nor was Harry Penrith, the Aboriginal activist, actor and writer better known as Burnum Burnum, who saw the headstone in January 1988 and hoped to retrieve Yemmerrawanne's remains and return them to Australia. [23]

References

Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions, G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793

Notes

[1] Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793)

[2] University of London School of Oriental and African Studies, Marsden Collection, Anon, Vocabulary of the language of NS Wales in the neighbourhood of Sydney, Marsden Collection, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, London, Notebook C, MS 41645, c1791, 4.11

[3] Reverend JK Shaw-Brooke, Parish Register, St. John’s, Eltham.

[4] 'Stone or rock' - - - keba', Anon, Vocabulary of the language of NS Wales in the neighbourhood of Sydney… University of London School of Oriental and African Studies, Marsden Collection, Notebook C, MS 41645, c1791, Marsden Collection, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, London, Notebook C, MS 41645, c1791 p 26.15

[5] ‘Yuremany’ [Yemmerrawanne], Inscription on reverse of silhouette portrait, B10 f14, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW

[6] Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793); Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions, G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793, 86n (Footnote)

[7] Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions, (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793), 64-65

[8] Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions, G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793 64-66

[9] Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions, G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793, 86n (Footnote)

[10] Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, including an accurate description of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions, G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793, 102

[11] London Packet, 28 May 1793; General Evening Post, 28 May 1793

[12] Morning Post, London, 10 June 1793

[13] 'A Song of the Natives of New South Wales', Edward Jones, Musical Curiosities … London, 1811,British Library, London, R.M.RM 13.f.f5, f. f15; Steve Meacham, Right back at us: Bennelong's song for 1793 London, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 September 2010; Keith Vincent Smith, '1793: A song of the Natives of New South Wales', Electronic British Journal, Article 14, 2011, http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2011articles/article14.html, viewed 11 February 2015

[14] Robert Jameson, 'Journey of a Voyage from Leith to London 1793', quoted in Jessie M Sweet, 'Robert Jameson in London 1793', Annals of Science, no 23, London, 1963, p, 102. Information from Richard Neville, Mitchell Librarian, State Library of New South Wales

[15] Morning Post, 29 May 1974

[16] National Archives Kew, Treasury Board Papers, T1Series, 1783-1840, 'Paid the Grave diger [sic] for turfing &c', 6 June 1794

[17] National Archives Kew, Treasury Board Papers, T1Series, 1783-1840, 'Tomb stone for Yemmerawanyea [£] 6 16 6', May 1794

[18] 'A campaign to bring home Australia's first 'ambassador', The Canberra Times, 9 February, 1991

[19] Liam Bartlett, Howard Sacre, Glenda Galtz, 'Lost the Plot', 60 Minutes, Channel Nine, 22 April 2007, http://sixtyminutes.ninemsn.com.au/stories/liambartlett/262243/lost-the-plot, viewed 11 February 2015

[20] Geoffrey Robertson, 'Losing the Plot', The Bulletin, 26 April 2007

[21] Geoffrey Robertson, Dreaming too Loud: Reflections on a Race Apart (North Sydney: Random House, 2013)

[22] 'Pilgrims from a world away', The Times, 1 February 1982

[23] 'Aborigines want remains returned', The Canberra Times, 30 January 1988

.