The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Coffee

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

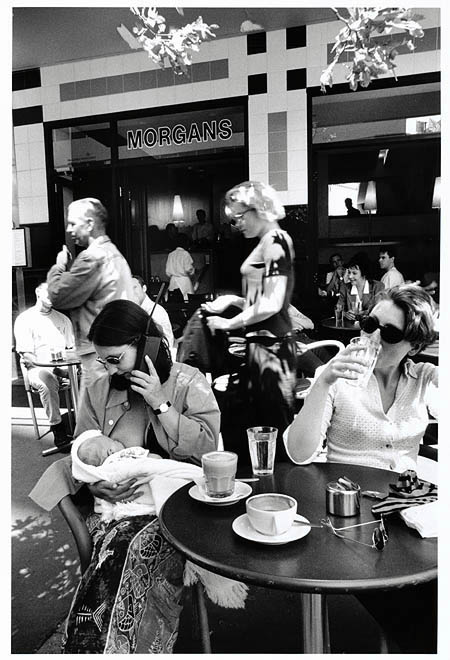

A [media]convict colony set up by the tea-drinking English was unlikely to become one of the major coffee consuming countries in the world. Even in 1901, Australia's government statistician estimated that coffee consumption was only one-tenth that of tea. But today, Australia ranks high on a world scale for per capita coffee consumption, and Sydney is sometimes derided as a city that is home to the 'latte-sipping, book-reading, chattering classes'. This transformation has been due partly to the impact of immigration from coffee-drinking cultures since World War II, and partly to changing fashions, especially among the young.

Sydney's first coffee

Yet [media]right from the city's beginnings, coffee has been around. Sydney's first coffee was unloaded in 1788 with the First Fleet. They had picked up coffee seeds and plants in Rio de Janeiro on their way to Sydney Cove, and the coffee seedlings were planted in the first garden at Government House. Unfortunately, the climate did not favour the bean, and it failed to become a commercially viable crop.

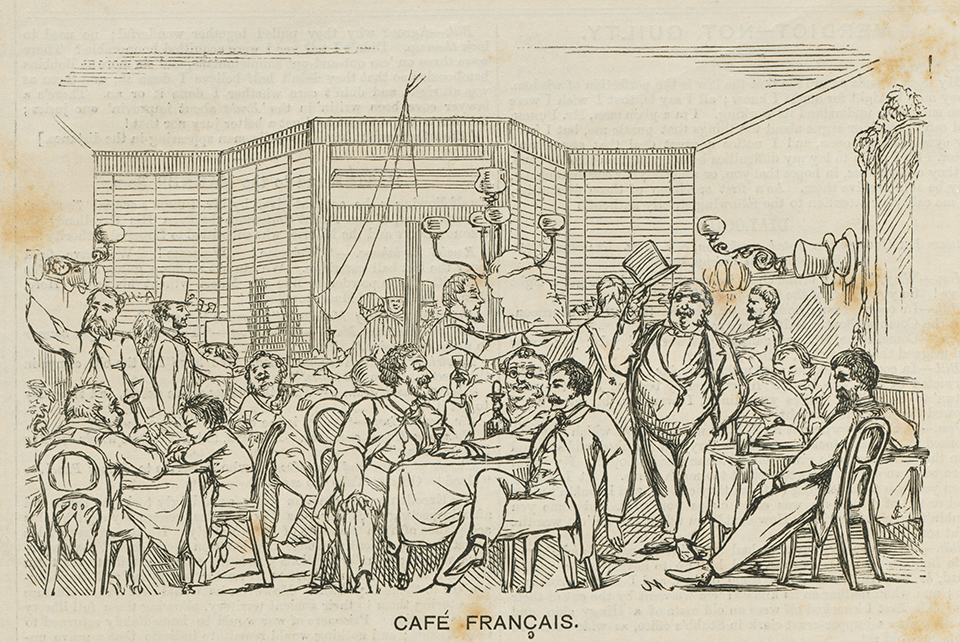

Coffee [media]was constantly imported during the nineteenth century, spurred by the influx of migrants from Europe and America during the gold rushes of the 1850s. It was the economic boom generated by the gold rushes that saw the establishment of Sydney's first Parisian-style café restaurants, serving café au lait and café noir to sophisticated Sydneysiders.

Beating the booze

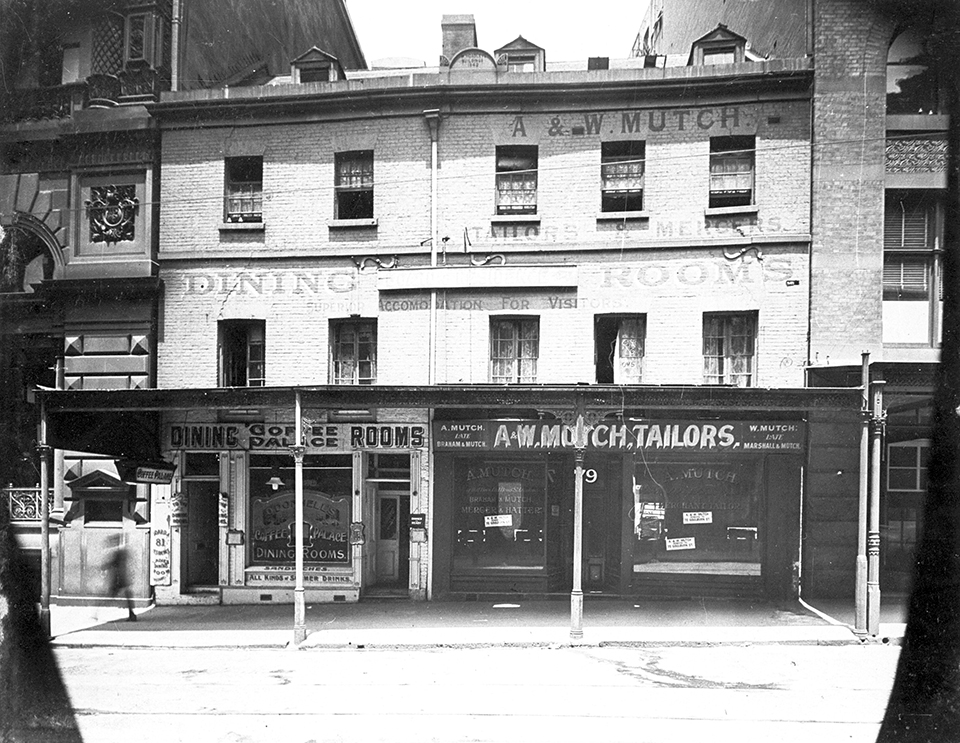

The [media]problems of another beverage – alcohol – led to a boom in coffee's attraction. The temperance movement, keen to provide alternatives to the ubiquitous pubs and associated drunkenness, gave encouragement to the establishment of Sydney's first coffee palaces. These had dining halls and accommodation, games, smoking and reading rooms, and were advertised as being family friendly, providing a congenial atmosphere for women and teetotallers.

[media]According to the Memorandum of Association of the Sydney Coffee Tavern Company, coffee palaces were 'houses, rooms, street stalls, and other places of a like nature in and around Sydney… [where] no wine, ale, or intoxicating liquors shall be sold or consumed'.

The era of coffee palaces

[media]A growing number of coffee palaces were established in Sydney from the late 1870s. [1] The No 2 Coffee Palace opened in Pitt Street in 1880, with a conservatory and marble-topped tables. It was described as giving 'the impression of a first-class Parisian café'. In the next few decades, coffee palaces appeared all around Sydney. The City of Sydney archives contain references to a large number of coffee palaces between the late 1890s and the 1930s. In them, references are made to the Crescent Coffee Palace, the Grand Central Coffee Palace, the North Sydney Coffee Palace, the Haymarket Coffee Palace, the Victoria Coffee Palace, the Exchange Coffee Palace, the Universal Coffee Palace, the Post Office Coffee Palace, the Federal Coffee Palace, Burney's Coffee Palace, the Emporium Coffee Palace, the Brighton Coffee Palace, and Ellis's Coffee Palace. They all belonged to the city's streetscape in the years prior to World War I and even Redfern had its own coffee palace.

Coffee was so popular and such a part of Sydney's culture that Australian troops in Heliopolis in Egypt during World War I set up their own coffee (and tea) shop. It was advertised in bold letters as 'SYDNEY, tea and coffee, first class'.

The coffee palaces were often driven more by reformist zeal than by good business sense, and many of them were relatively short-lived. Several of the buildings developed another life after the coffee palace fad faded. The Sydney Coffee Palace in Woolloomooloo became the Sydney Eye Hospital, and more recently, smart apartments, while the Great Western Coffee Palace, at the corner of Hay and Sussex streets, eventually became the Burlington Hotel, and then the Kien Hay Centre, still in use today.

Immigrants and servicemen – coffee comes into its own

For the [media]average Sydneysider, tea remained a more popular beverage than coffee and it was only in the 1930s that Britain overtook Australia as the leading tea-drinking nation in the world. Ironically, it was during the years of the Great Depression that coffee started to come into its own in Sydney. The city embraced the modernism of the 1930s which saw the advent of cinemas, new theatres, and watering holes for the smart set, such as the glamorous new palais de dance, the Trocadero.

[media]The Cahill family [2] and Ivan Repin [3] opened coffee-selling venues for a clientele keen to enjoy a little sophistication at a reasonable price. Cahill's restaurants seemed to attract the refined and middle classes, while Repin's cafes were patronised by

refugees from Hitler's Europe in long overcoats and carrying briefcases, champion chess players, artists with canvasses and paints … authors with manuscripts.

It was Ivan Repin who started [media]the practice of roasting coffee at the entrance to his coffee shop, so that the enticing aroma would attract passers-by. [4]

The war years also had an impact on Sydney's awareness of coffee. The massive influx of American servicemen gave a further stimulus to coffee consumption and appreciation, not only in Sydney's commercial venues, but also among those Sydneysiders who wanted to get on more intimate terms with the Americans.

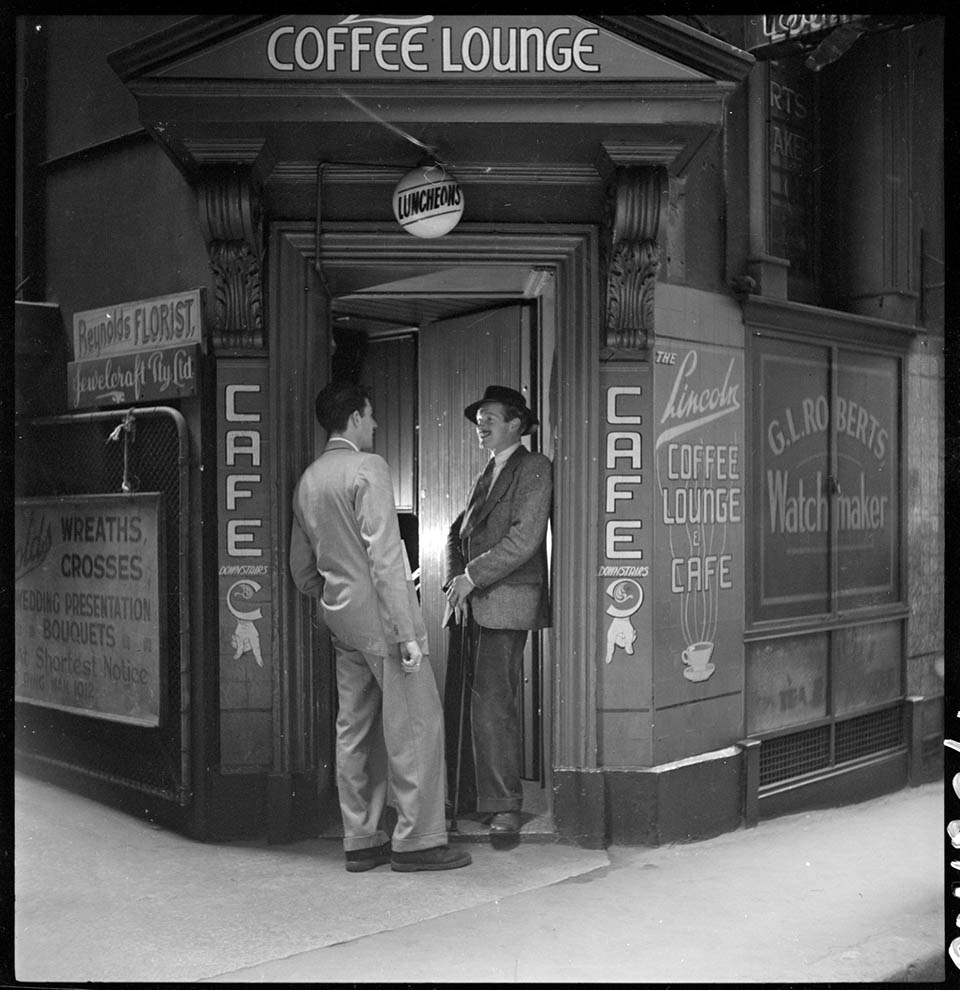

[media]The lifting of government controls on the import of coffee in the 1950s coincided with the arrival of hordes of coffee-loving immigrants, and by the early 1960s coffee 'lounges' were appearing in Sydney's suburbs, heralding the beginning of Sydney's current love affair with its coffee.

References

Nicola Teffer, Coffee Customs, Exhibition Catalogue, Customs House, City of Sydney archives, nd

City of Sydney Archives

'Aussie cafe culture accounts for 'biggest growth in coffee', Australian Food News website, http://www.ausfoodnews.com.au/2010/03/04/aussie-cafe-culture-accounts-for-biggest-growth-in-coffee.html, viewed 20 July 2011

Notes

[1] Searching the City of Sydney Archives for the term 'coffee palace' brings up a long list of documents, covering the council's interactions with the proprietors of many coffee establishments.

[2] Kerry Regan, 'Cahill, Teresa Gertrude (1896–1979)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, HYPERLINK "http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/cahill-teresa-gertrude-12831" http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/cahill-teresa-gertrude-12831, viewed 20 July 2011; Object 91/1068 'Placemat, restaurant, Cahill's Tudor Hall', Powerhouse Museum Collection website, HYPERLINK "http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/?irn=111445" http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/?irn=111445, viewed 20 July 2011

[3] IJ Bersten, 'Repin, Ivan Dmitrievitch (1888–1949)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/repin-ivan-dmitrievitch-11509, viewed 20 July 2011

[4] Nicola Teffer, Coffee Customs, Exhibition Catalogue, Customs House, City of Sydney archives, nd

.