The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Garden Palace

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Garden Palace

[media]If you mention fireworks at midnight on New Year's Eve, or the 2000 Olympics, most people would agree that Sydney knows how to host a party. But back in 1879, when it was decided to hold an International Exhibition, we were not quite so sure of ourselves.

The fashion for holding exhibitions, where countries could show off their industrial and manufacturing might as well as their agricultural riches and artistic skills, began in 1851 with the London Exhibition. It was housed in the purpose-built Crystal Palace. Exhibitions followed in other European cities and in Philadelphia in the United States. Paris was particularly fond of holding them. Then Sydney, a place not noted for its advanced industrial sector, and very far away from other places that were, decided to have a go.

A palace in the gardens

[media]A fine set of gates leading into the Botanical Gardens on Macquarie Street announces the venue, the Garden Palace, home of the International Exhibition. Beyond the gates, a circular garden bed recalls the former location of the dome of the Palace building. Everything about this building was flamboyant. Viewed from Farm Cove and measured against today's landmarks, the building stretched from the Conservatorium, across the Cahill Expressway and in front of the State Library. Its four towers and spectacular wooden central dome dominated the skyline, dwarfing all other buildings. One of the great attractions of the exhibition was to ascend the north tower in Sydney's first hydraulic lift, to enjoy rare elevated views of the harbour.

Part of the Gardens and most of the Domain became a vast fair ground covered with machinery halls, an art gallery, temporary buildings for livestock, bandstands, stalls and eateries. Approximately 49 acres (20 hectares) of the gardens were handed over for the exhibition, with six hectares covered in buildings. This was not what was originally intended.

Difficult beginnings

[media]When members of the Agricultural Society decided to stage an exhibition in 1877, perhaps as much because Melbourne was organising one as for any other reason, they had no idea what they were letting themselves in for. The Society's Exhibition building in Prince Alfred Park was to be the venue, and previous annual agricultural exhibitions would be the model. The colonial government agreed to the idea, provided that 'no pecuniary liability' was to be incurred by them.

But when the proposal was made public, there was far more interest than had been anticipated. The Society got cold feet. Clearly their vision had not been large enough, and neither their funds nor their building would be adequate. A rift developed between those supporting the Society's 'rural' charter and what was now being branded a 'Sydney' exhibition. Fearing bankruptcy, they cancelled the whole thing, only to have the governor, Sir Hercules Robinson, step in and insist that it must go ahead, with a public subscription to fund it. The money did not pour in, and the colonial government voted against a subsidy.

But word had gone out, and exhibitors were planning to come. According to the Sydney Morning Herald,

the world has forced upon us an unexpected expansion … We objected to this thing initially, but it has gone too far ... we must take a favoring tide on the flow. [1]

Eventually, in January 1879, the government reluctantly granted £50,000. This was considerably more than the original estimate of £18,000, but nothing like the final official figure, which came in at around £250,000. Unofficial calculations went a lot higher still.

Building the palace

By now a whole year had been lost in squabbling, and the exhibition was due to open in August. The contractor thought December might be possible. The government settled for September. Building began before plans had been finalised, and the colonial architect, James Barnet, modified his drawings on the run, as the contractor, John Young, discovered what building materials would be available, and when. No tenders were let, proper processes were ignored and as confirmation of entries came in from around the world, more and more buildings were hastily added to the complex.

At the time of building, there was high unemployment in Sydney. As soon as approval for the building was given, men began to gather around the Domain gates in the hope of finding work. There was no need to advertise for workers, although sometimes there were 2000 on site. They were employed around the clock, using electric light for night work for the first time in Sydney. In the early stages, the lighting flickered and cast shadows, and was widely considered unsafe. The unions protested at the long shifts and dangerous work, but when the carpenters struck for what amounted to danger money they were unsuccessful, with the Herald cheerfully reporting that

the firm and commendable action of the Government has completely disheartened the men, and crushed the spirit of rebellion in them. [2]

At least one man was killed on the site, and others were injured.

As preparations progressed, the newspapers were full of doubts. Where would the visitors stay? What if the city's water supply gave out, as it sometimes did? What would they think of our crooked streets and our badly repaired street pavements? We didn't even have a completed Town Hall. What on earth did we think we were doing? How would people get to the site?

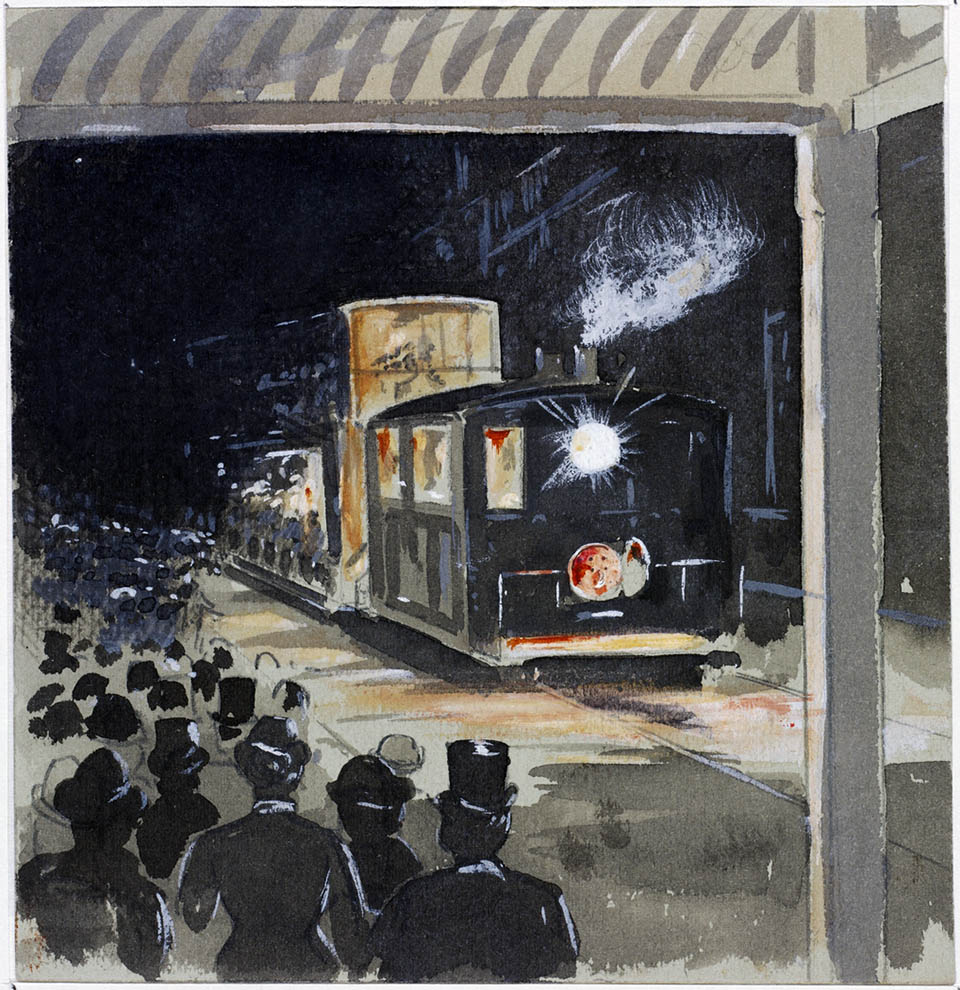

[media]This last problem was solved by fast tracking the installation of a line for a steam tram, another first for Sydney. Built in 16 weeks, it ran from the Redfern terminus, along Elizabeth Street to Hunter Street. This expedient piece of urban infrastructure turned out to be one of the main attractions of the Exhibition, with a million passengers riding the tram by the time the exhibition closed. Its construction had been approved only on the basis that it was removed after the show was over, but Sydneysiders took to it with enthusiasm, and it became the first permanent line of Sydney's ad hoc tram system.

But the two biggest worries were 'what if the buildings were not completed on time?' and 'what if it rained?' They weren't, and it did. The official opening had to be postponed, and despite the best efforts of Charles Moore, the Director of the Gardens, the plantings drowned and the gardens of the Garden Palace were more correctly described as bogs in the opening weeks of the exhibition.

The Exhibition

But everything eventually came together. There were ongoing criticisms of exhibits not in place on time, of the entrance fee, of the quality of the food and so on. Yet Sydneysiders enjoyed the holiday atmosphere and the many supporting musical and cultural events, and, overall, they were mightily impressed with the building. Of the grand opening, in the rain, one commentator said,

Signor Giorza arranged the music, and ably assisted by a chorus of 700 voices, 50 instrumentalists and the Grand Organ, he succeeded in conducting the entire ceremony to a brilliant and most enjoyable conclusion to the plaudits of the assembled thousands.

Much of the ambivalence over the wisdom of staging the exhibition arose from the realisation that manufacture and industry was not really a local strength. The London Times understood this too, reporting that

the eyes of the world [are] centred for once on Australia, and at seeing a lively competition between American, European and British manufacturers. [3]

Although there were fine local exhibits, it was clear to many that the local role was primarily to foot the bill.

[media]There were 724 classes of goods and produce on exhibition, from huge pieces of machinery to fine porcelain. When the idea of holding an exhibition was first proposed, one Member of Parliament had complained that exhibitors would use it to foist on Sydney the wretched rubbish they could not dispose of at Paris, but in the event there was a lot of interest in the new and exciting things on show. Today, one of the most valuable pieces in the Sydney Town Hall collection is a Sevres vase, one of a pair that was exhibited in the French Court at the Exhibition. It was subsequently presented as a gift to the citizens of Sydney by the French Republic.

Because of the long distances involved, some of the exhibits had to be in the form of models, rather than the genuine article. Was there perhaps room for a little poetic licence in the models of turnips and beets sent by some London seed merchants in order to show the great size of produce grown using their stock?

Poetry was the order of the day, and from the official cantata written by Henry Kendall to the ravings of the more ecstatic scribblers to the daily newspapers, everyone expanded on the 'garden' motif for all it was worth. There may have been a cultural cringe over how Sydney as a city would stand up to the world's gaze. But as a civilisation, there was no doubt that the British way of life that Sydney symbolised was making a fine contribution in the southern land, 'the wilderness a garden made'. That this garden was British, derivative and youthful sat easily with most participants, and the fact that there were ethnological displays about the Australian Aborigines, creating the illusion that they were not present, did not seem out of place – although any visitor to the exhibition had only to walk down Macquarie Street beyond the Palace to meet some of them.

Fire

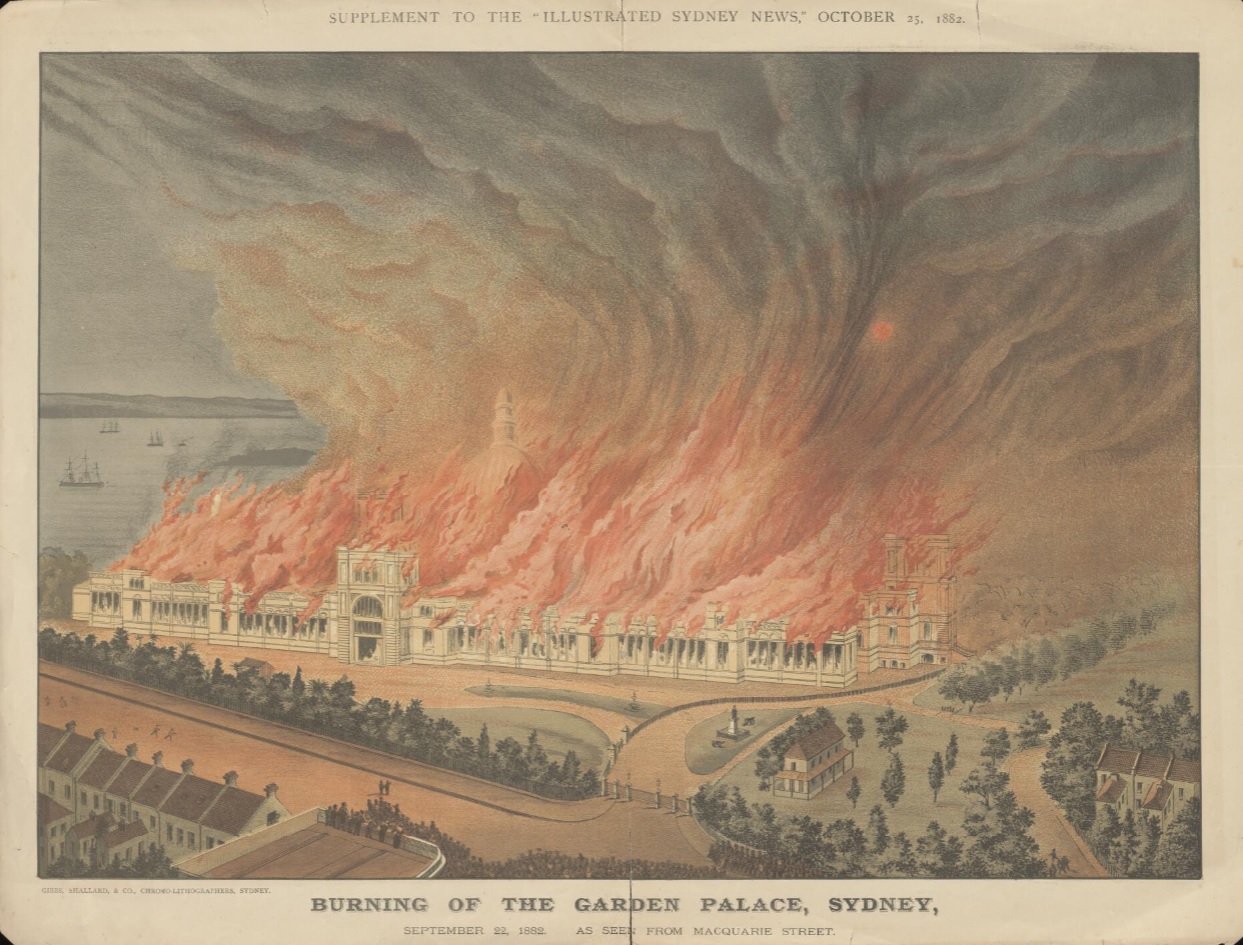

[media]When one enthusiast penned the hope that the exhibition would 'lead to universal brotherhood, to universal commerce, to better times, and better men, and things' he was going further than most, but few anticipated that the end would be quite as deflating as it was. [4] At dawn on 22 September 1882, the Garden Palace spectacularly burnt down, with reports of blackened iron pieces landing as far away as Rushcutters Bay.

[media]By this time the building was being used for occasional events and as office space for various government departments. Records, including those of land occupations, the 1881 Census details, and railway surveys, all went up in flames. So too did 300 uninsured canvasses from the Art Society's annual exhibition, the grand organ and the foundation collection of the Technological and Mining Museum (now the Powerhouse Museum).

No-one was ever charged, although arson was generally suspected. Many mourned the loss of the building, and a fresh outpouring of eulogistic poems appeared in the press, along with a new round of self criticism over the waste of it all. And more than a few people expressed some satisfaction that at least the people of Sydney now had their Botanical Gardens back.

References

Shirley Fitzgerald, 'The Garden Palace and Sydney's International Exhibition of 1879', in Lenore Coltheart, (ed), Significant Sites: History of Public Works in New South Wales, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1989, pp 67–95

Notes

.