The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Stained glass

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Stained glass

Sydney has a [media]distinguished share of Australia's rich heritage in stained glass, a heritage which resulted from a fortunate combination of historical factors. Having reached a peak in thirteenth-century Europe as part of Gothic architecture, stained glass declined by the seventeenth century and was virtually a lost art by the eighteenth century. Then, in the mid-nineteenth century, a revival occurred as a result of the resurgence of interest in, and renewed practice of, Gothic architecture. In England it was connected to the Anglo-Catholic religious revival, and by the 1860s England led the way in the design and manufacture of stained glass. [1] This revival coincided with a period of strong economic growth in the Australian colonies, the result of the gold rushes and continuing pastoral expansion. Prosperity brought migrating architects and stained glass artists to Australian shores. There was a building boom, particularly in churches, and stained glass became part of the boom. [2]

From as early as the 1840s, stained glass was imported into Australia, mainly from Britain, and by the later nineteenth century thousands of windows were being imported. In addition, a healthy rapport developed between architects and stained glass artists, and by the 1860s stained glass firms had opened in Melbourne and Sydney. Stained glass became an integral part of both ecclesiastical and secular architecture, and an industry thrived from 1860 to 1914.

Sydney's imported stained glass

Two [media]major British firms, John Hardman & Co of Birmingham and Clayton & Bell of London, supplied stained glass to Australia in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Some of their best work may be seen in Sydney.

The windows made by Clayton & Bell for the University of Sydney's Great Hall remain a landmark in Australian stained glass. [3] The building was designed by Edmund Blacket, who had migrated to Australia in 1843 fresh from the influence of Augustus Welby Pugin and the Gothic revival. He exemplifies the rapport between architects and stained glass artists which was to prove so fruitful, and he was a major influence on the incorporation of stained glass into the University buildings. The Great Hall windows, made between 1856 and 1858, were the first ambitious program of stained glass to come out of the nineteenth-century revival, and consequently received much publicity in London at the time; [media]royal approval was required before the windows were dispatched to the colony of New South Wales. [4] Thirty-five men of learning and invention, exclusively British, are portrayed life-size on either side of the hall. They are ranked chronologically and in groups, beginning with the Anglo-Saxon historian, the Venerable Bede, and ending with the late eighteenth-century explorer and cartographer, Captain James Cook. At [media]either end of the hall two 14-light windows represent the Universities of Cambridge (on the east) and Oxford (on the west), and a 19-light bay window, set off the dais, portrays the monarchs of Britain. In place by 1859 when the Great Hall was opened, the windows transform this architectural environment and charge it with meaning, expressing the foundations and ideals of the University.

While Clayton & Bell were pre-eminent for secular [media]stained glass, exemplified at the University of Sydney, John Hardman & Co were the leading exporters of glass for Sydney's cathedrals. Edmund Blacket designed St Andrew's Anglican Cathedral, and from 1861–68 Hardman sent out windows forming a narrative scheme on the life of Christ. The high level of their skill is everywhere apparent; panels in the choir depicting Mary Magdalene won a prize at the 1864 South Kensington Exhibition. In addition, the firm's architectonic skill in handling themes on a grand scale is evident in the east and west windows of St Andrew's. [5] For a [media]grand iconographic scheme, however, Hardman's achievement at St Mary's Catholic Cathedral is remarkable. From 1881 to 1937, the firm made all the windows for St Mary's to form a vast unified program rich in meaning: typology is incorporated throughout, and even includes historical scenes in the nave windows which tell the story of the early days of the Catholic Church in Australia. [6]

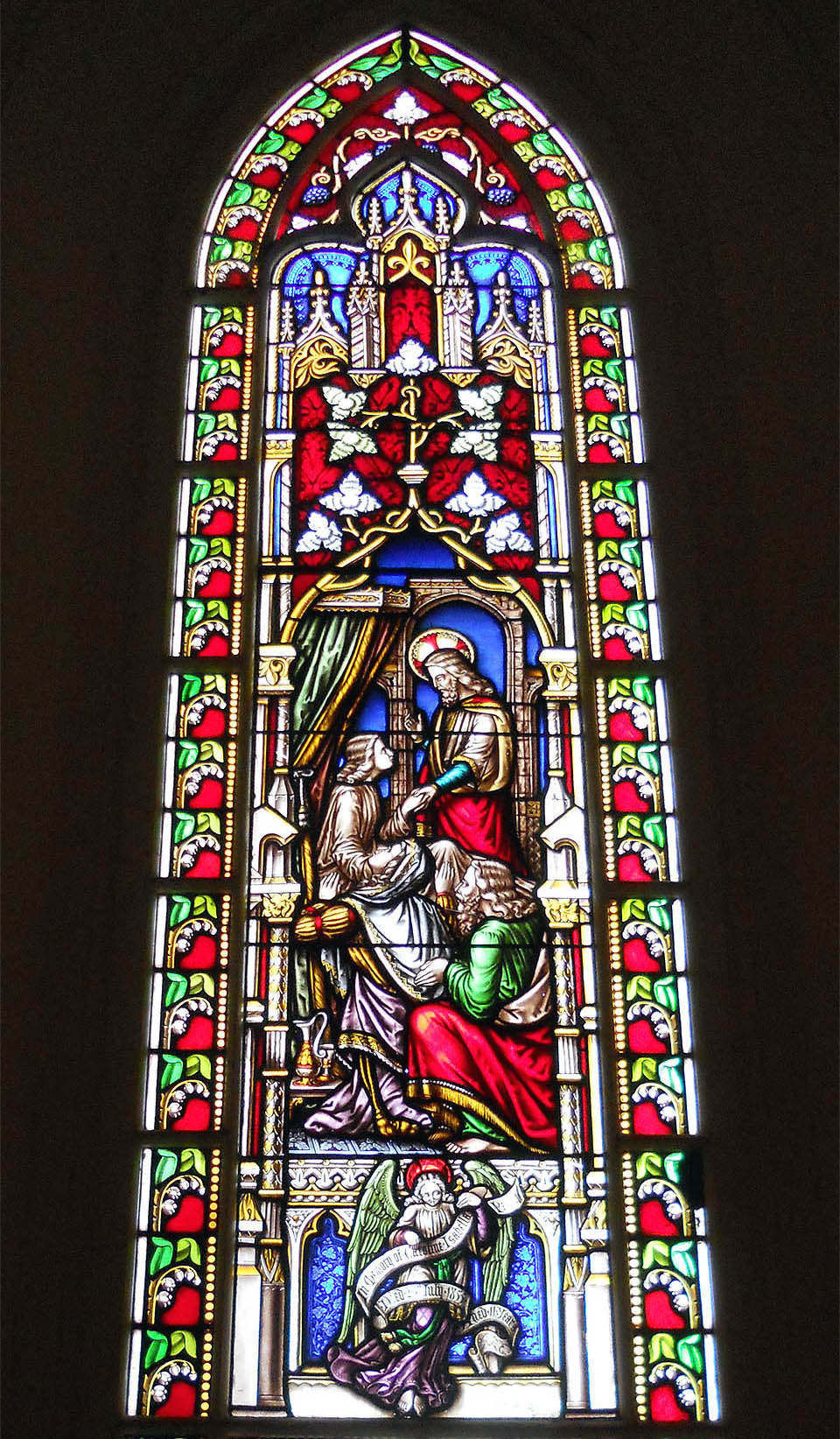

While Hardman was the leading British maker to supply glass to Sydney churches, a singular example of imported stained glass arrived in 1860 from Charles Clutterbuck of Essex – the east window of another Blacket church, Holy Trinity, Millers Point (the Garrison church). At such an early date, this dramatic window, exemplifying Clutterbuck's pictorial 'Renaissance' style, must surely have been 'one of the most famous sights in any Sydney church'. [7] Another [media]unique work, dating from 1856, is the east window at St Paul's Anglican church, Cobbitty, the memorial to Caroline Perry, a young girl who died at the age of 11. It was designed by her uncle, the London artist William Warrington (1796–1869), on the subject of the raising of Jairus's daughter. It is the only window by Warrington in Australia. [8]

The eminent English firm of Morris & Co exported principally to Adelaide, but in Sydney their work may be seen at All Saints' Anglican church at Hunters Hill, which holds two three-light Morris windows made to designs by Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), including an inspired portrayal of Christ at the Transfiguration.

Stained glass for [media]residences was rarely imported, but an outstanding example survives at Fairwater in Double Bay, a house built in 1881–82 for a Sydney stockbroker and his bride. [9] J Horbury Hunt was the architect and, like Blacket, Hunt was particularly knowledgeable and enthusiastic about stained glass. He sent to England for the glass which, on the basis of style, can be attributed to Nathaniel Westlake (1833–1921) of Lavers, Barraud & Westlake. Right from the front door of Fairwater, stained glass is visually and thematically compelling. The heraldic arms and mottos of husband and wife are worked in the fanlight, and in the sidelights female figures represent Hospitality and Peace. In the library, a four-light window depicts the sciences and the arts. The story of Evangeline, a favourite subject with Horbury Hunt, holds pride of place on the staircase window and represents faithful love. The range of windows at Fairwater bears witness to ideals and benefits of civilised life and, more specifically, to the Victorian taste and social values of the architect and his clients.

Sydney's locally made stained glass

[media]The first [media]professional stained glass artist in Sydney was John Falconer from Glasgow, who opened a studio in Pitt Street in 1863. By 1875 he was joined by Frederick Ashwin from Birmingham. Some of Falconer & Ashwin's earliest work may be seen in the dome of the vestibule of the Sydney Town Hall. The vestibule served as Sydney's original town hall, and the dome was installed in 1877, depicting an array of allegorical figures representing the strengths needed by the colony (Industry, Truth, Plenty, Temperance, Justice, Peace, Liberty, and Prudence). In 2011 the dome needed repair and the City of Sydney Council drew on the advice of one of Australia's experienced restorers, Kevin Little (born 1930). [10] Also in the 1870s, Falconer & Ashwin designed windows for St James's Catholic church, Forest Lodge, which were in place when the church opened in 1878. [11]

Frederick Ashwin [media]taught the first Australian-trained stained glass artist, John Radecki. A Polish immigrant, Radecki was employed by Ashwin from 1885 and eventually became the chief designer of F Ashwin & Co and subsequently of John Ashwin & Co. His work is ubiquitous in Sydney churches, and notable examples are the east window of Christ Church Saint Laurence, installed in 1906, and the chapel windows (1930s) at St Scholastica's Convent, Glebe. In the sphere of public buildings, Radecki and the firm of F Ashwin & Co contributed to the opulence of the Queen Victoria Building (1898), a showpiece in the city. Massive fanlights of stained glass – 'cartwheel' windows – were incorporated into this arched and domed building and face George and York Streets. The glass was restored as part of a major restoration project in the 1980s, and the building won a Heritage Award for restoration in 1987. [12]

Perhaps Radecki's most [media]stunning achievement, however, is the vaulted ceiling of stained glass in the Grand Hall of the Commonwealth Bank, Martin Place. Installed in 1928, the panels depict various industries – grazing, agriculture, mining, shipping, and building – as the sources of the nation's wealth. Brilliant blue skies, rosella parrots, and merino sheep express optimism and pride, confidence that was to disappear in the Depression of the 1930s. [13] After John Ashwin died in 1920, Radecki became the proprietor of John Ashwin & Co, and the firm continued, with mainly ecclesiastical commissions, until 1955.

The [media]firm of Lyon, Cottier & Co opened in Sydney in 1873. John Lamb Lyon and Daniel Cottier had worked together as apprentices in Glasgow, and although only Lyon migrated to Australia, Cottier retained a guiding hand in the business. Scotland, especially the Glasgow area, was an important centre for the revival of stained glass, and ecclesiastical and secular glass developed there side-by-side within the broader field of decoration. Lyon and Cottier's Scottish background and their association with the Pre-Raphaelites made them equally at home with ecclesiastical and secular work. [14]

Some of their best work may be seen at All Saints' Anglican church, Hunters Hill, a church designed by that known enthusiast for stained glass, Horbury Hunt. The east window (the Te Deum), installed in 1889, had been Lyon & Cottier's main exhibit in the Centennial International Exhibition of 1888 in Melbourne; it was greatly admired and the design was adapted for Grafton Cathedral (also by Hunt). The windows in the south nave portraying the Evangelists and the Apostles display Lyon & Cottier's fine draughtsmanship as well as the warm golden tones which are a hallmark of their style.

These [media]strengths are also evident in Lyon & Cottier's designs for St Andrew's College, University of Sydney, made between 1876 and 1889. In the library, on the staircases, and at the front entrance, stained glass illuminates the meaning of St Andrew's as an educational institution, while at the same time expressing the college's, and the artists', Scottish heritage. Thus, while Dante, Homer, and Chaucer figure prominently, St Andrew's also displays a virtual portrait gallery in stained glass of famous Scots. [15]

Besides their [media]work for churches and institutional buildings, Lyon & Cottier made much glass for houses. [16] A favourite theme was Cottier's design of the Seasons, which he used also for residences in Scotland. [17] Strongly Pre-Raphaelite in style, the Seasons were made for different houses, with some variation in execution. Examples survive at Booloominbah in Armidale, New South Wales, and in the following Sydney residences: Arlington in Croydon; Gladswood House, Double Bay; 4a Fernleigh Gardens, Rose Bay; Lyndcote, Hunters Hill; and as a painted ceiling decoration at Government House. The Gladswood House series (c1875) is distinguished by the warm tones characteristic of Lyon & Cottier, and the statuesque figures of Flora and Pomona at the entrance are also Cottier's own designs.

A remarkable piece of [media]work supplied by Lyon & Cottier is the Captain Cook window at Cranbrook, Bellevue Hill (now Cranbrook School). James White, a Member of the Legislative Council, bought Cranbrook in 1873 and the architect Horbury Hunt remodelled it for him, which included the installation of the Captain Cook window. Another Captain Cook window was exhibited by Lyon & Cottier at the Melbourne Exhibition of 1875, as well as a Captain Cook window at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876, the only stained glass from Australia. [18] These windows were no doubt part of the centenary celebrations for Cook's voyages of the 1770s. While Lyon & Cottier are known to have supplied the window at Cranbrook, the artists who worked on it remain unidentified. However, Cottier's international contacts make it likely that the artist was commissioned by him. The subject is treated with great technical skill as well as imaginative and enthusiastic attention to detail. There are nine panels: Captain Cook is portrayed in five, in various nautical settings; two other panels show Cook's ships; another depicts Sir Joseph Banks and Dr Solander conferring over an exotic plant, while the central panel portrays two officers looking mystified and startled at the sight of a kangaroo. History is recorded in these panels with authentic nautical details, physical movement, and human reactions. It is a work of dynamic realism – no wonder it is referred to affectionately at Cranbrook as 'our magic window'.

In the [media]late 1880s, at the height of the building boom, Lyon & Cottier employed 30 to 40 people, and until John Lyon's death in 1916, they were one of Australia's leading stained glass firms. Artists who trained with them – WB Marshall, David McColl Little (grandfather of Kevin Little mentioned above) and Alfred Handel – went on to establish their own studios. Alfred Handel is best remembered for a unique window he designed for St Bede's Anglican church, Drummoyne. The architect Emil Sodersten was appalled but Handel took the ancient form of a rose window and treated it imaginatively, with Australian wild flowers, waratahs dominating, forming the design. In the 1940s Norman Carter likewise designed a bold series of windows for the clerestory of St Andrew's Cathedral which depict events in Australian history, including missionaries preaching to the Aborigines. [19]

The Sydney [media]firm of Goodlet & Smith, first established in 1855 as timber merchants, diversified into stained glass in the 1880s. They executed some of the designs of the French artist Lucien Henry, who became a leading influence in Sydney's art world and was a bold designer of stained glass. [20]

His work is best seen in the Sydney Town Hall, built to celebrate the centenary in 1888. The stained glass dome of the vestibule (the earlier Town Hall, referred to above), is tame compared with the work of Henry in the main (Centennial) hall. The glass was installed in the clerestory of the auditorium and on the staircases leading to the galleries. Henry's belief in the expressive power of the decorative arts to build national character finds full-blown expression in these designs. In the clerestory almost every variety of Australian fruit, crop, and flower is depicted, with recurring motifs of a plough and the rising sun, while the staircase windows are heady manifestos of national pride.

A larger than life-size Captain Cook dominates the window of the northern staircase: he stands on the deck of a ship, telescope in hand, every inch the great navigator, while the stars of the Southern Cross are placed around him. His ships Endeavour and Discovery are represented in stylised form in the border, together with floral emblems of the British Isles. The figure of Cook is drawn with great clarity, and a three-dimensional effect, rare in stained glass, has been achieved. The window is enhanced by its setting on a grand staircase which is lit by a gasolier decorated with waratahs shaped in metal. Most of all, the colours in the glass – blue dominating, combined with red and gold – contribute to a boldness which is very much part of the meaning of the window.

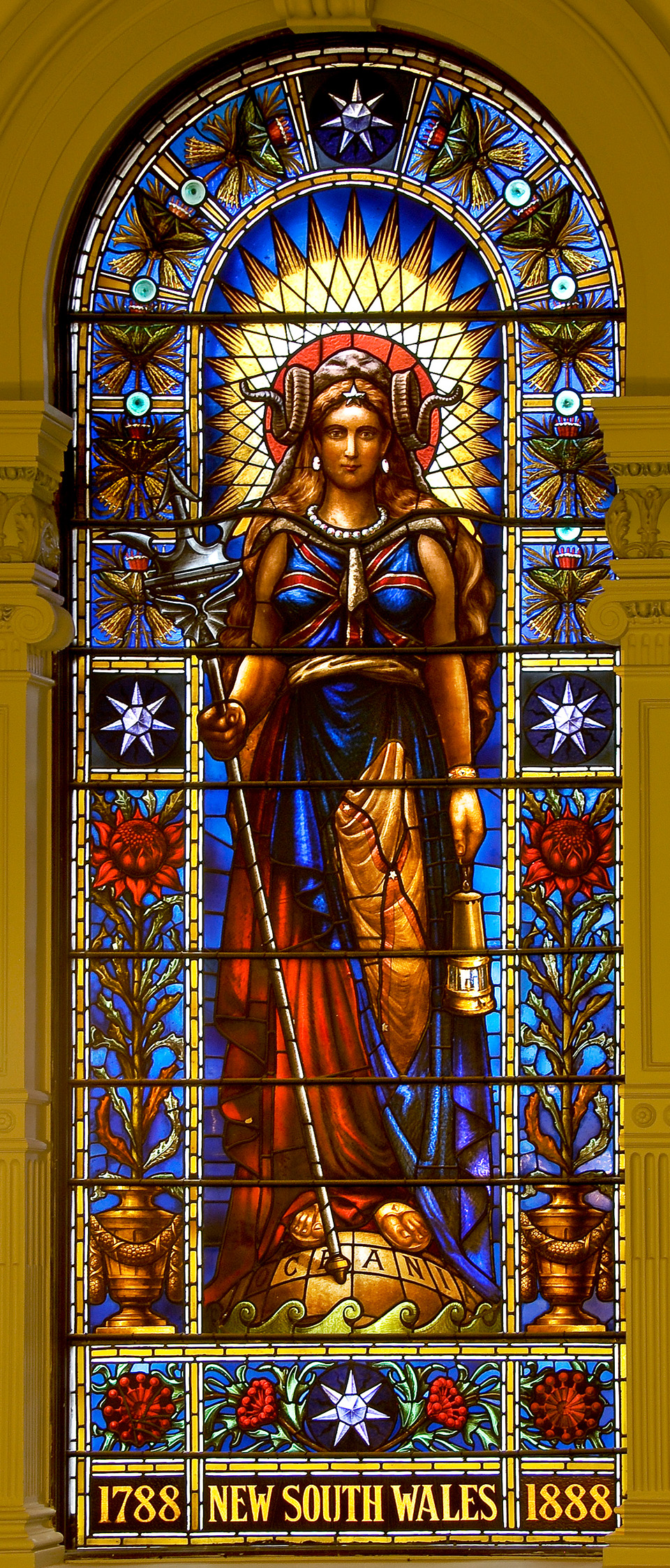

The [media]companion window, on the southern staircase, displays the same skilful draughtsmanship, three-dimensional effect, and bold use of colour. The figure depicted is even more arresting than Cook, an extraordinary woman who represents Australia. She is replete with national icons – ram's horns on either side of her head and the skin and wool of a sheep for her headdress, a jeweled necklet, a miner's lamp in one hand, a trident in the other, the Union Jack as part of her dress, a brilliant sun behind her head, and a globe inscribed 'Oceania' beneath her sandaled feet. The stars of the Southern Cross, together with waratahs, stenocarpus, and flannel flowers, are depicted in the border and side lights. When this window was installed in 1889, a lengthy explication was published for the aid of the (no doubt mystified) public. [21]

Goodlet & Smith made windows for many Sydney residences in the 1880s and 1890s, and wherever there are Australian themes – characteristic of this centennial period – the colours and style suggest the hand of Lucien Henry as, for example, the brilliant waratahs at St Cloud (1893) in Burwood.

The [media]glass merchant Frank G O'Brien opened in 1924 and Arthur G Benfield became director of the stained glass department. Benfield carried out numerous ecclesiastical commissions in the wider Sydney area, but an interesting collection of his work may be seen in the New South Wales State Library building, facing Shakespeare Place. [22] The windows were installed c1940 during the building's construction. The Manuscript windows in the foyer cast a golden glow from the eastern sun and suggest the richness of an illuminated text. The Chaucer window and the Sydney Gazette window are in the main reading room, now the Mitchell Library, but Benfield's masterpiece is an exquisite series in the Shakespeare Room depicting the Seven Ages of Man from Shakespeare's play As You Like It.

Decline, revival, and survival of stained glass

Stained glass is [media]vulnerable to the vicissitudes of changing architectural styles and altered economic conditions. Although the art seemed to have a glowing future in Australia in the early years of the twentieth century, World War I, the Depression of the 1930s, and World War II all had negative effects. While ecclesiastical commissions never entirely dried up, stained glass was in decline by the 1940s. Architects had lost touch with the art, with the result that it was no longer an integral part of architecture as it had been during the late nineteenth century. [23]

A [media]revival began in the 1960s, not with the renewal of an industry supported by large firms, but rather through the emergence of one-person studios. [24] The Sydney artist Philip Handel, son of Alfred Handel, was a prolific designer of church windows and is well known for his memorial windows made in 2003 for the Church of St Michael and All Angels at Sandakan, Sabah (Borneo). The Melbourne artist David Wright (born 1948) won an award to mark Australia's bicentenary in 1988 for his window in St James's Anglican church, King Street, Sydney. This visionary work forms three walls of a side chapel and conveys symbolically, and in the colours of the Australian outback, the Creation, the Fall, and the Crucifixion. The most innovative designer from this period, especially for her imaginative introduction of Australian themes into church windows, was the South Australian artist, Cedar Prest (born 1940). In Sydney, her work may be seen in the Library of Macquarie University, North Sydney Shopping World, St Kevin's Catholic church, Eastwood, and the Sydney International Airport, where her wall of stained glass, High Tide East Coast, was installed in the arrivals hall in 1992.

Despite the vicissitudes of its history, stained glass is fortunately long-lived – the glorious windows of Europe's medieval cathedrals are still intact and vibrant after eight centuries. As long as Sydney's stained glass windows and the buildings which house them are protected, stained glass will have an enduring and glowing future in the city.

References

Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass (Photographs by Douglass Baglin), Murray Child, Sydney, 1991

Notes

[1] See Martin Harrison, Victorian Stained Glass, Barrie & Jenkins, London, 1980

[2] For a history of stained glass in Australia, see Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass (Photographs by Douglass Baglin), Murray Child, Sydney, 1991

[3] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 67–69

[4] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 67–68

[5] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 26, 27, 91

[6] Robin Hedditch, 'The Iconographic Program of the Stained Glass Windows in St Mary's Cathedral', Master of Heritage Conservation (Hons) dissertation, University of Sydney, 2002

[7] Joan Kerr, Our Great Victorian Architect Edmund Thomas Blacket (1817–1883), National Trust of Australia (NSW), Sydney, 1983, p 45. See also Danute Giedraityte, 'Stained and Painted Glass in the Sydney Area c 1830–1920', MA thesis, University of Sydney, 1983, pp 45–46

[8] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, p 94

[9] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 12, 27, 45–46, 63

[10] Particularly challenging work of restoration undertaken by Kevin Little was the Clutterbuck window at the Garrison Church, Millers Point – Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, p 35

[11] See Anne Wark, Armour of Light: The Stained Glass Windows of St James' Church Forest Lodge, Parish of St James, Forest Lodge, Forest Lodge, 2010

[12] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 10, 35

[13] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 65, 75

[14] Michael Donnelly, Scotland's Stained Glass: Making the Colours Sing, The Stationery Office, Edinburgh, 1997, chapter 2; Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 16, 33

[15] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, pp 68, 85

[16] Out of 106 designs from the collection of John Lamb Lyon made between 1876 and 1915 and now held in the Mitchell Library, 18 are for institutions and businesses, 22 for churches, and 66 for private residences. See Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, p 16

[17] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, illustration, title page and p 38

[18] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, p 41

[19] On these windows by Handel and Carter, see Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 96, 108; on Carter see also pp 34, 68, 108, 109

[20] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 15, 40–41

[21] Quoted in Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, p 70

[22] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 70–71

[23] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, p 34

[24] Beverley Sherry, Australia's Historic Stained Glass, Murray Child, Sydney, 1991, pp 34–36, 71–72, 89, 113–14

.