The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Building the Sydney Harbour Bridge

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Sydney Harbour Bridge

[media]The iconic Sydney Harbour Bridge spans the Harbour at its narrowest point between Dawes and Milsons Points. It is a double-hinged, riveted steel arch bridge with a reinforced concrete deck and reinforced concrete pylons and at the time of its completion in 1932 it was considered the epitome of modern bridge design and engineering ingenuity.

Early proposals to bridge the Harbour

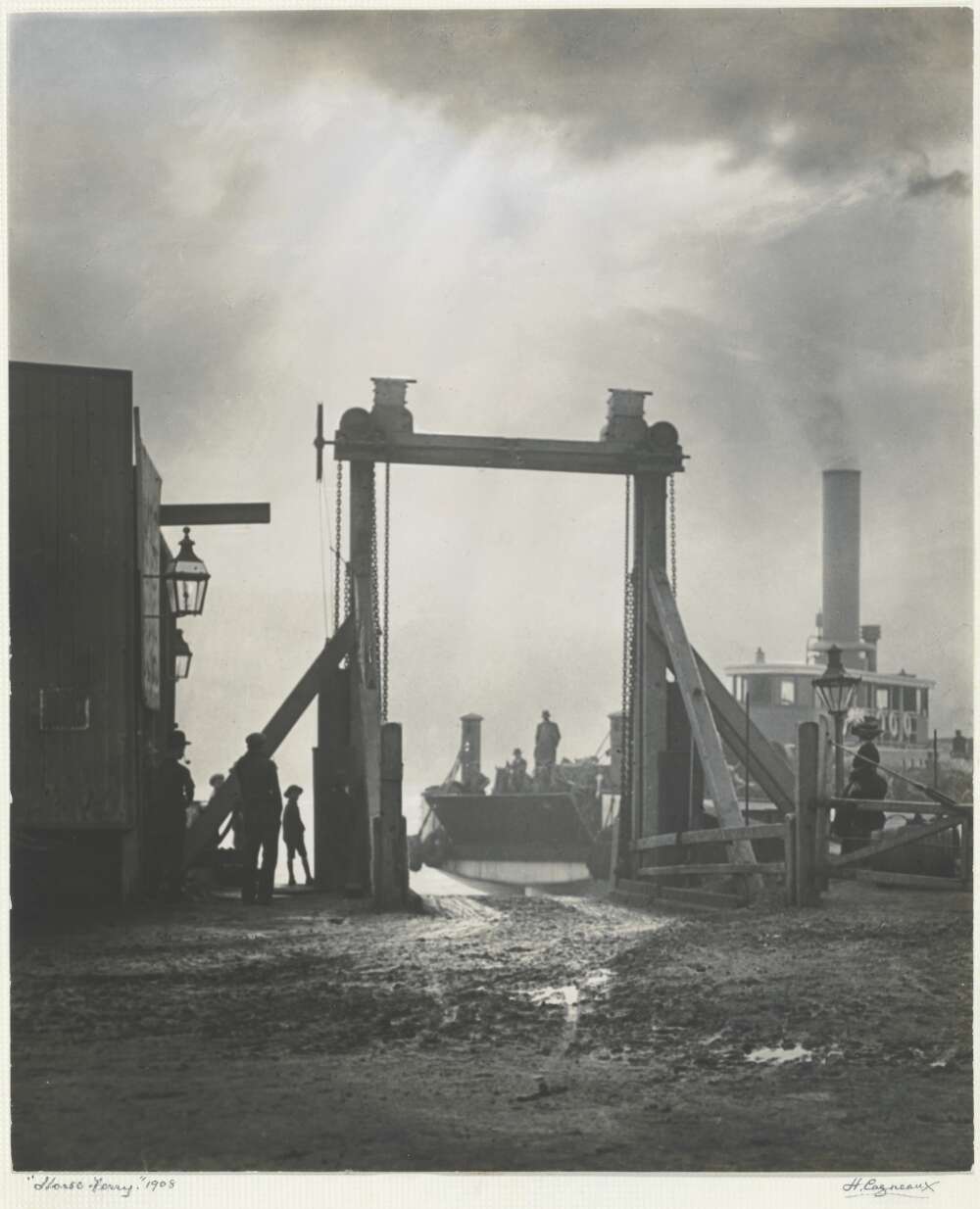

[media]Proposals to join the north and south sides of the Harbour with a bridge were first put forward in 1815 by convict architect Francis Greenway. In the first half of the nineteenth century, Sydney was formed around Sydney Cove and later, as the population grew, it developed around the Harbour and its tributaries to the north, west and south. European settlement on the northern side of the Harbour began in earnest after 1814, following a land grant to ex-convict Billy Blue, who began the first ferry service across the Harbour soon after. Watermen continued to provide passage to the north shore until the 1840s, when Sydney's first vehicular ferry service was established between Dawes and Milsons Point. Vehicular and passenger ferries continued to be an important form of public transport on Sydney Harbour for the remainder of the nineteenth century.

Although there had been a number of plans to build a bridge across the Harbour throughout the nineteenth century, none were realised. This was chiefly because it was costly and technically difficult to build bridges over large, tidal expanses of water such as Sydney Harbour. As well, throughout the nineteenth century, timber had been the most prevalent material for bridge construction in New South Wales, with durable masonry and cast iron bridges reserved for heavily traversed routes, or for the railways, as they were expensive to build in terms of both skilled labour and cost of materials.

Prefabricated steel and concrete

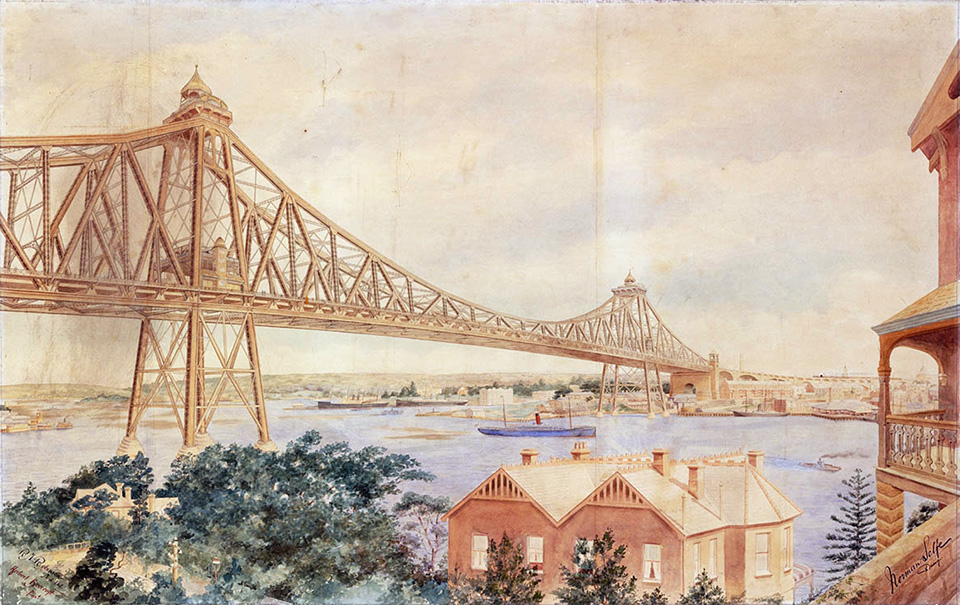

[media]The construction of a bridge across Sydney Harbour became a reality by the early twentieth century, with advances in bridge engineering technology internationally, alongside developments in the local manufacture of prefabricated steel and reinforced concrete. The advantage of steel in particular, apart from its cost effectiveness, was that it was durable and malleable enough to span wide tidal bodies of water.

The NSW Government began to seriously investigate the possibility of building a bridge across the Harbour at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1900, the New South Wales Government of the day lobbied for the proposed bridge to be built by a private company. To this end, the Minister for Public Works called for a worldwide competition for its design and construction and set up an advisory board to review the tenders.

There were no winning entries for this competition, however, as the specifications for the bridge had to be rewritten. The competition was reopened the following year with amended specifications. A design by the Sydney-based engineer Norman Selfe was announced the winner. In 1904 the project was stalled indefinitely when the government changed, leaving Selfe bitterly disappointed.

Bradfield and Dorman Long and Co

[media]The completion of the Sydney Harbour Bridge was largely due to the efforts of one man, the engineer Dr JJC Bradfield. Bradfield's long involvement with the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge began in 1903, when he was appointed secretary to the advisory board set up to review the bridge tenders. Bradfield was steadily promoted within the Department of Public Works and by 1912 he had responsibility for the Sydney Harbour Bridge branch and for the electrification of the suburban railway. Bradfield's dual responsibilities within the department suggest that the Bridge and Sydney's public transport system were to be integrally linked.

[media]Bradfield continuously reworked the design of the Sydney Harbour Bridge from 1912 to 1929, despite the disruptions of World War I (1914–1918), which reduced the numbers of his staff. By 1922 he had eventually settled on a two-hinged steel arch design as the ideal bridge for the Harbour, primarily because of its durability.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge Act was passed and assented to on 24 November 1922. Under the Act, tenders were called to construct a bridge between Dawes and Milsons Point. Tenders were closed on 16 January 1924. The winning tenderer was the British engineering firm of Dorman, Long and Co. The contract was signed on 24 March 1924. One of the conditions of the tender was that materials had to be sourced and manufactured in NSW where possible. Granite for the piers and pylons was quarried at Moruya on the NSW south coast, and just over twenty percent of the steel was produced in Australia. The remainder of the steel was manufactured in England.

[media]There is some controversy about who designed the Bridge, owing to the nature of the contract between Dorman Long and the NSW Government. Obviously Bradfield had a long association with the design of the Bridge but Ralph Freeman, as the consulting engineer for Dorman Long, also had claim to be the Bridge designer. Freeman was responsible for completing the final drawings under the terms of the contract. A bitter rivalry developed between the two men.

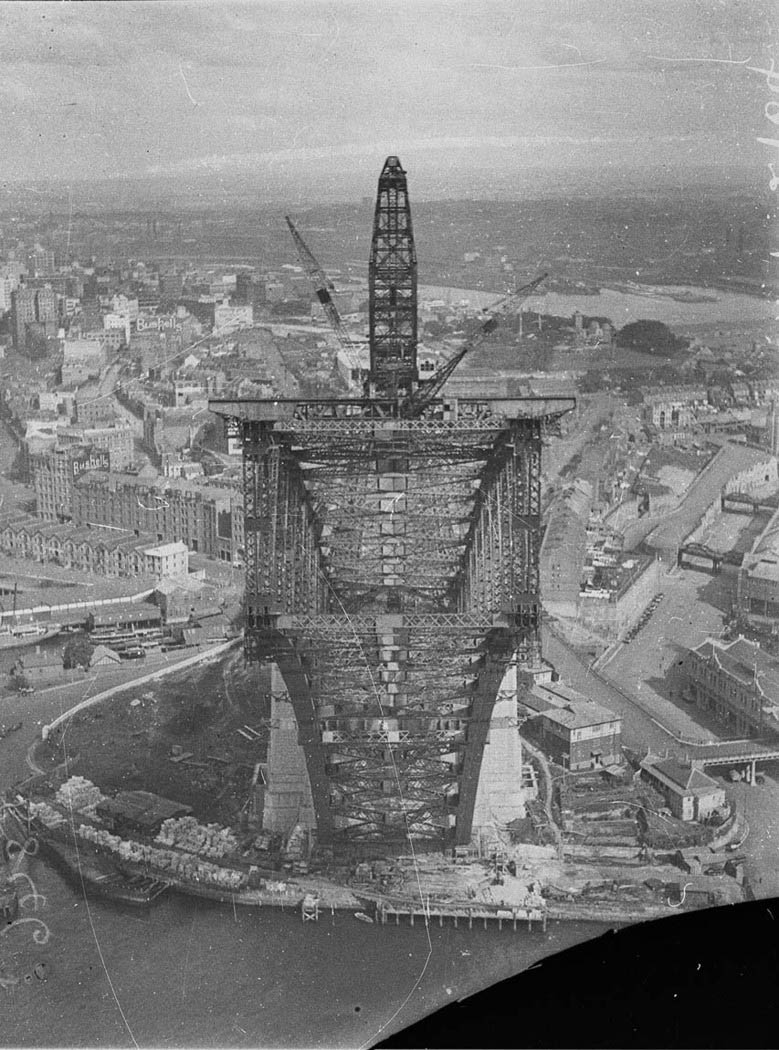

The construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge

[media]The Bridge took eight years to build, from 1925 to 1932, including the approaches and supporting roads. Over 2,000 people were employed to work on the bridge, including engineers, boilermakers, ironworkers and stonemasons. Although the workers were overwhelmingly Australian, the workforce had a multi-national character, with skilled labourers, such as stonemasons and ironworkers, brought from overseas. Sixteen men died while working on the bridge, and accidents on the job were frequent, due to the hazardous nature of the work. (For example, the job of the rivet cooker involved throwing red-hot rivets to the rivet catchers, who caught the rivets in buckets and then hammered them into place.) Nevertheless, Bridge workers received relatively good wages and conditions, and although the unions were vigilant, there was minimal industrial action in the eight years it took to complete the Bridge.

[media]In September 1930, the painstaking work to position the prefabricated grids, girders and plates into place paid off when the arch was neatly joined. The road deck was laid soon after, and work began on building the pylons, which anchor the Bridge at either end. The Bridge pylons were faced with granite, as a nod to more traditional bridge design.

By February 1932, the Bridge was completed. That month, the strength of the deck was tested with ninety-six locomotives laid end to end along the railway tracks on the eastern side of the Bridge.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge was a massive undertaking, in terms of both engineering ingenuity and financial outlay. Its completion in 1932 represented international advances in bridge technology in the early twentieth century.

The opening ceremony, and the scandalous disruption

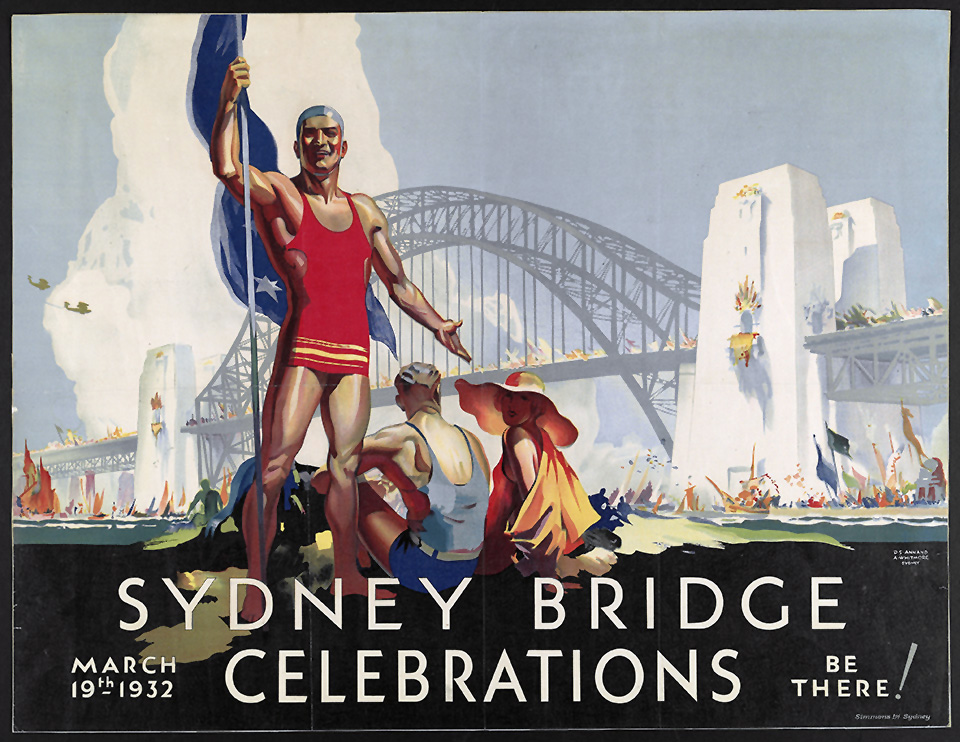

[media]The NSW Premier of the day, Jack Lang, officially opened the Sydney Harbour Bridge on 19 March 1932. The opening ceremony was famously disrupted when Francis De Groot, a member of the fascist, anti-Lang New Guard, rode across the Bridge on horseback and slashed the ribbon with a sword. After De Groot was taken away by the police the ceremonial ribbon was held in place and Lang cut it, declaring the Bridge open.

Celebrations to open the Bridge were restrained as it was the middle of the economic Depression in the early 1930s, and as a consequence there was limited money in the public purse. Yet the public were overwhelming enthusiastic about the completion of the Bridge, with over 750,000 people lining the streets and Harbour to watch the opening and subsequent pageantry.

[media]After they had finished working on the Bridge, many of the former Bridge workers faced lean times as the Depression continued to bite. Some former Bridge workers had to wait until the war years to work in their trades again. Other workers were luckier, and were employed to work on Luna Park on the site of the former Bridge workshops at Lavender Bay.

The Harbour reshaped

[media]Construction of the Bridge was paid for initially by a tax, and later by a toll that continues to be levied today for Bridge maintenance.

The southern pylon is situated on Dawes Point, which was the site of the former defences for Sydney Harbour. Some of these buildings were used as the Dorman Long offices during Bridge construction and were later demolished to make way for the Bridge. The Bridge approaches cut a swathe through the neighbourhoods on either side of the Harbour, most significantly The Rocks and North Sydney.

Although Bradfield envisaged that the Bridge would be an integral part of Sydney's public transport system, with provision for trains and trams, the rise of the motorcar throughout the twentieth century meant that road transport across the Harbour became increasingly dominant. Construction began on the Cahill Expressway in the 1950s, which again saw the carving up of the suburbs surround the Bridge approaches on the southern side of the Harbour. The construction of the Warringah Expressway in the 1960s had a similar impact on suburbs on the north shore.

In 1992, the Harbour Tunnel was completed in order to reduce crossing time and traffic congestion for car users. In recent times there have been proposals to add additional road decks to the Bridge, to accommodate the increasing traffic flow between the city and the north shore. Sadly, however, Bradfield's dream of incorporating the Bridge as part of Sydney's public transport system has failed. Yet the Sydney Harbour Bridge remains one of Sydney's most important icons, and an enduring legacy to Bradfield, Freeman and the thousands of men who worked to build it.

Sources and Further Reading

This article was originally published as 'Sydney Harbour Bridge', City of Sydney, About Sydney, History and Archives, Sydney History, 2005–2014, http:/www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/AboutSydney/HistoryAndArchives/SydneyHistory/HistoricBuildings/SydneyHarbourBridge.asp

Lenore Coltheart, ed. Significant Sites: History and Public Works in New South Wales. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1989

David Ellyard and Richard Raxworthy. The Proud Arch: The Story of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Sydney: Bay Books, 1982.

Peter Lalor. The Bridge: The epic story of an Australian icon – the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2005.

Caroline Mackaness, ed. Bridging Sydney. Sydney: Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, 2006.

North Sydney Heritage Centre. Pamphlet 12 Sydney Harbour Bridge. North Sydney Council, Library, Pamphlets and Leaflets. http://www.northsydney.nsw.gov.au/Library_Databases/Heritage_Centre/Leaflets_Publications

North Sydney Heritage Centre. Pamphlet 28 Taking the Ferry. North Sydney Council, Library, North Sydney Heritage Centre, Pamphlets and Leaflets. http://www.northsydney.nsw.gov.au/Library_Databases/Heritage_Centre/Leaflets_Publications

Roads and Maritime Services New South Wales, About, Environment, Protecting Heritage, Oral History. Sydney Harbour Bridge Maintenance Cranes. http://www.rms.nsw.gov.au/about/environment/protecting-heritage/oral-history-program/sydney-harbour-bridge-maintenance-cranes.html

Peter Spearritt. The Sydney Harbour Bridge: A Life. Kensington: UNSW Press, 2007

State Records New South Wales. Archives In Brief 37 - A brief history of the Sydney Harbo ur Bridge . http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/guides-and-finding-aids/archives-in-brief/archives-in-brief-37

State Records New South Wales. Archives In Brief 38 - Records relating to the Sydney Harbour Bridge . http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state- archives/guides-and-finding-aids/archives-in-brief/archives-in-brief-38

State Records New South Wales. Around the Rugged Rocks. http://srwww.records.nsw.gov.au/public/gallery/rocks/rocks.html

State Records New South Wales. Sydney Harbour Bridge Photo Colle ction. http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/digital-gallery/browse-photo-investigator/photos-in-our-collection/sydney-harbour-bridge-photographs

Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority, Dawes Point Battery Site, 1791-1932, http://www.shfa.nsw.gov.au/content/library/documents/0508749D-0BD4-36CA-12E059DBDF512B18.pdf