The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

A distinguished lady doctor

Dagmar Berne c1890, State Archives and Records NSW (9873_a025_a025000112)

Dagmar Berne c1890, State Archives and Records NSW (9873_a025_a025000112)

The Daily Telegraph, 26 December 1894, p4 via Trove

The Daily Telegraph, 26 December 1894, p4 via Trove

Thomas Ley: Politician and murderer

Portrait of TJ Ley 1925 Courtesy National Library of Australia (nla.pic-an23460617)

Portrait of TJ Ley 1925 Courtesy National Library of Australia (nla.pic-an23460617)

Smith's Weekly, April 19. 1947, p11 via Trove

Smith's Weekly, April 19. 1947, p11 via Trove

Nicole Cama is a professional historian, writer and curator, and the Executive Officer of the History Council of NSW. She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity.

Listen to the podcast with Nicole & Nic here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Nic Healey on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15-8:20am to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

The Dictionary of Sydney needs your help. Make a tax-deductible donation to the Dictionary of Sydney today!

Nicole Cama is a professional historian, writer and curator, and the Executive Officer of the History Council of NSW. She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity.

Listen to the podcast with Nicole & Nic here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Nic Healey on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15-8:20am to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

The Dictionary of Sydney needs your help. Make a tax-deductible donation to the Dictionary of Sydney today!Terry Smyth, Denny Day: The Life and Times of Australia’s Greatest Lawman

Terry Smyth, Denny Day: The Life and Times of Australia’s Greatest Lawman

Terry Smyth, Denny Day: The Life and Times of Australia’s Greatest Lawman

Ebury Press, 2016, 352 pp., ISBN: 9780857986825, p/bk, AUS$34.99

Award-winning writer Terry Smyth has taken on the extraordinary, and regularly overlooked, story of Edward Denny Day in Denny Day: The Life and Times of Australia’s Greatest Lawman, The Forgotten Hero of the Myall Creek Massacre (2016), from Ebury Press. True crime tales are often criticised for being cheap and trashy, a quick way to make some money and unsettle the community with a few photographs of terror and violence. Domestic normalcy transformed, in a few moments of chaos, into a crime scene. This stereotype, of quick and dirty volumes, is becoming increasingly challenged by many writers, including Smyth. Indeed, Smyth’s writing style is perfect for telling a true crime story – a genre that is often a blend of biography, history and judgement of wrongdoers – in an age when such stories are becoming increasingly rigorous in their research and sophisticated in their narrative styling. For true crime, though often criticised, is a difficult genre to ‘get right’. Too much detail and the author is glorifying evil while taking advantage of the victim. Too little detail and the author is charged with sanitising history, glossing over the brutal nature of some types of crimes. The use of language is crucial. The reader often comes to the text knowing the ending. We know the victim. We know the perpetrator. What we want to know is how and why. We want to understand the machinery that brought about justice and to feel reassured that the world order, grossly disrupted, has been restored. In this respect, Smyth delivers. The very first line – “Sydney sits cowering it its cove, its face turned seaward, lying back and thinking of England” – demonstrates Smyth’s capacity for irreverence and insightfulness. This level of scene-setting is critical for true crime, for crime is often the story of context: the events that converged to bring about tragedy. This text tells a particularly difficult story for the villains are especially heinous: they are the men who perpetrated the Myall Creek Massacre in which 28 Aboriginal men, women and children were murdered in 1838. In this way, this book is one about murder, frontier violence and the traumas of colonisation. Day was the lawman who, with a small party of mounted police, tracked down and arrested eleven men. Seven of those men would hang in Sydney for their crimes. Yet, Day was not lauded as a hero instead he was, as Smyth notes, a man who was “scorned and shunned, fiercely attacked by the press, powerful landowners and the general public”. Today, he is largely forgotten, his entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography typically short and his obituaries excluding reference to his greatest achievement. Day is certainly not presented as perfect, for no man is and Smyth’s admiration is tempered by some realism. What is clear, and consistent, is that Day had a strong sense of justice which Smyth reveals with skill. Read this book as the true crime story of Denny Day and the men of the Myall Creek Massacre. Read it also, as an important story of New South Wales and of law and justice in colonial Australia. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, September 2017 For a preview of the book or to purchase online, visit the Penguin Books website here.Ross Gibson, The Criminal Re-Register

Ross Gibson, The Criminal Re-Register

Ross Gibson, The Criminal Re-Register

The University of Western Australia Publishing, 2017, 152 pp., ISBN: 9781742589558, p/bk, AUS$22.99

Ross Gibson’s new work, The Criminal Re-Register (2017) from University of Western Australia Publishing, is a fabulous re-imagining of a mid-twentieth century copy of a Criminal Register. In a pre-database age, the Register was a volume that was produced every year by Sydney Police containing details on a vast array of criminals. Collated over a twelve-month period, the Register was an almanac that was distributed to police stations far and wide. The profiles of criminals, their methods, their madness all laid bare to facilitate apprehension (or the occasional interaction). It was, in short, the ultimate Crook Book. Gibson found his 1957 issue of the Register “ten years ago, along with a brown envelope full of unlabeled and undated photographic portraits in a Kogarah junkshop”. The content has been wonderfully re-written as a suite of poems that, as Gibson writes, has “messed” with the original which he “ransacked” for details to re-work to merge and play with. Brutality and creativity blend to produce a text that is compelling reading. This slim volume, only 152 pages, also presents as a beautiful object. The cover is elegant. The rich, cream pages are highly textured: challenging the idea that the world of crime is a world of black and white. Each word has been carefully chosen as well as thoughtfully situated on the page: the arrangements are both disruptive and striking. The blurred photographs appear, and linger, as memories just out of reach: Gibson calls these people ghosts. One of the more poignant inclusions in Gibson’s Re-Register is a set of descriptions of malefactors which offer perfunctory details of not-so-legitimate careers supplemented by some distinguishable traits. There is a “safebreaker and thief”, a “house-breaker and ladies man”, a “pretender and forger” and a “house breaker and cat burglar”. One felon “seldom wears a hat”, one is “careless with fingerprints” while yet another is “in the habit of sucking his left thumb”. Several are “addicted to drink”. This text reminds us that the criminal world, and the way it intersects with the non-criminal, is extraordinarily complex. The human cost of crime is sometimes borne by villains as well as victims. Sure, there are bad people that do bad things (the “razor slashers” and “sexual perverts”) but there are, too, those who have been crushed by their circumstances. Gibson’s work – of poetry and photography – is a soft lens with which to view a harsh world. The 1950s in Sydney was a decade of remarkable change: cars, commercial computers and televisions. There was mass immigration. There was the shadow of the Cold War. Perhaps the only constant was crime. Some criminal acts were perpetrated by the worst that society has to offer while some offenders were those who had honest jobs one day but found themselves drunkards and scoundrels the next. Crime and the issues that surround crime, including prevention and punishment, are difficult – emotionally and intellectually – to resolve. Here, poetry is a useful, if unlikely, tool to help us look at crime in a different way. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, September 2017 This book is available to preorder at the University of Western Australia Publishing website here.The Peapes ghost sign

The Peapes sign recently uncovered at Wynyard, September 2017 Photo courtesy City of Sydney

The Peapes sign recently uncovered at Wynyard, September 2017 Photo courtesy City of Sydney

Sydney Punch, August 26, 1865, p 524

Sydney Punch, August 26, 1865, p 524

Signwriters from Rousel Studios painting an advertising sign on a wall for Tooth’s K B Lager 1920s, Courtesy Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences (2002/105/1-2/71)

Signwriters from Rousel Studios painting an advertising sign on a wall for Tooth’s K B Lager 1920s, Courtesy Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences (2002/105/1-2/71)

Peapes & Company trade catalogue for 1897, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ML 658.87105/1)

Peapes & Company trade catalogue for 1897, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ML 658.87105/1)

The Home, Vol. 1 No. 3 (1 September 1920) p 47 via Trove

The Home, Vol. 1 No. 3 (1 September 1920) p 47 via Trove

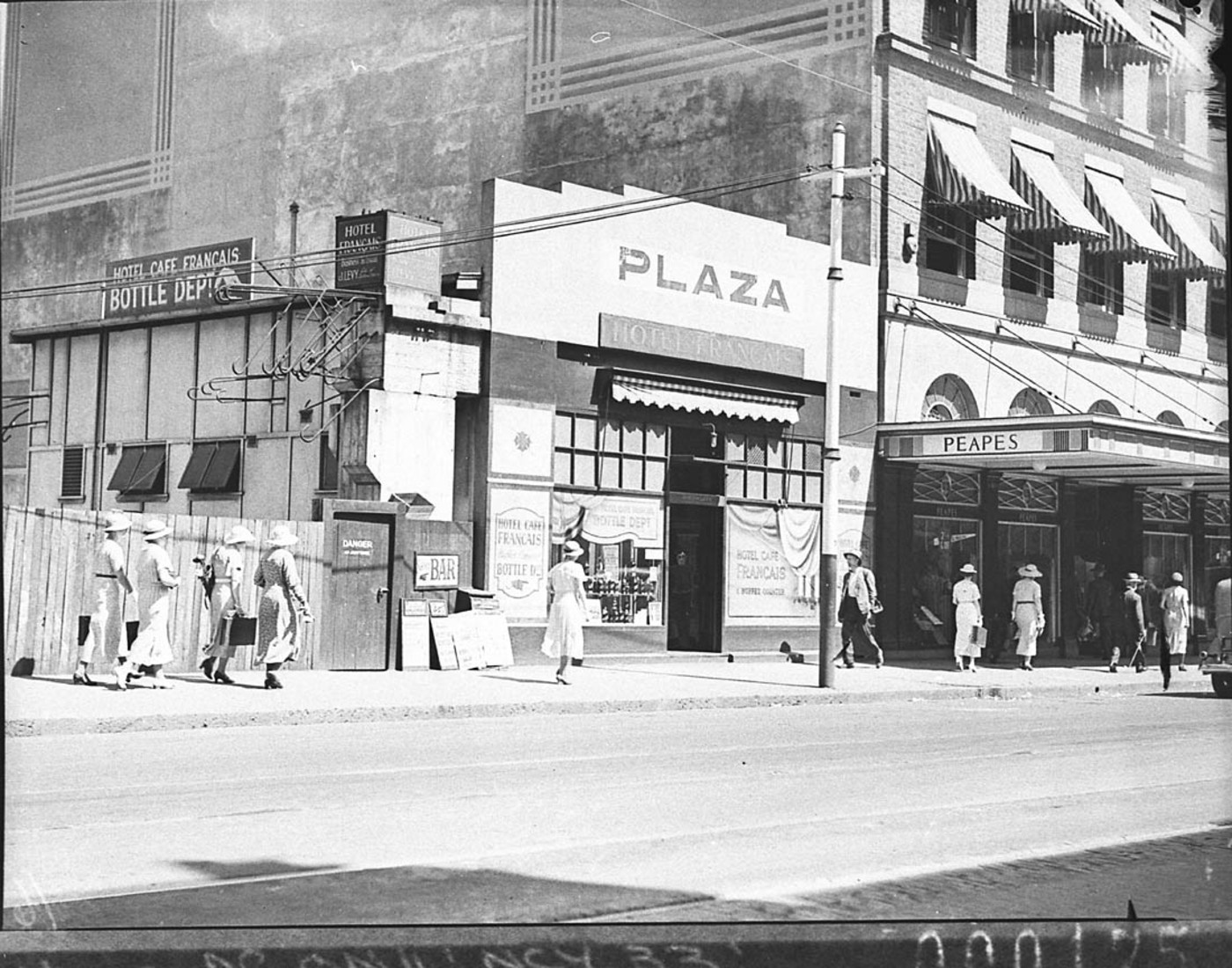

Plaza Hotel temporary bar and Peapes' Menswear Store next door January 1935, by Sam Hood, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Home and Away 11785)

Plaza Hotel temporary bar and Peapes' Menswear Store next door January 1935, by Sam Hood, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Home and Away 11785)

Peapes & Co advertisement in Stewart's hand book of the Pacific islands; a reliable guide to all the inhabited islands of the Pacific Ocean, for traders, tourists and settlers, 1919. Courtesy The Internet Archive

Peapes & Co advertisement in Stewart's hand book of the Pacific islands; a reliable guide to all the inhabited islands of the Pacific Ocean, for traders, tourists and settlers, 1919. Courtesy The Internet Archive

James Bray and his Museum of Curios

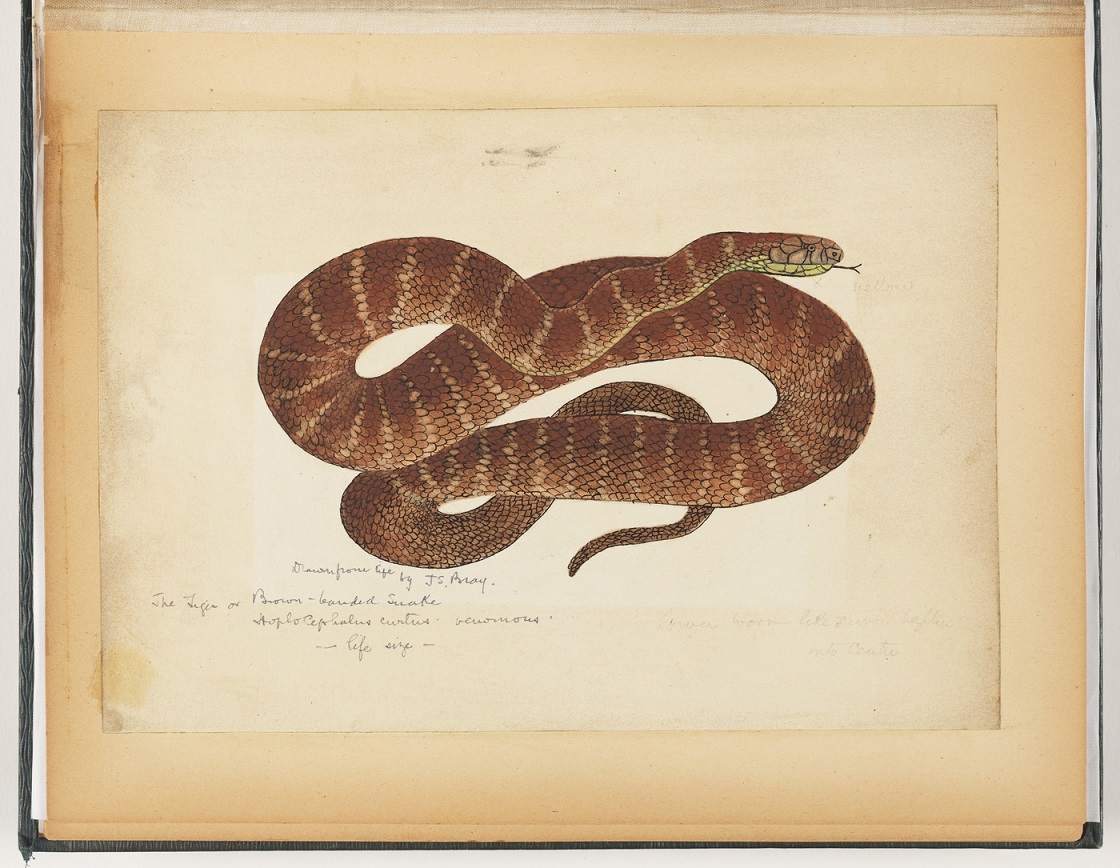

Drawn from life by JS Bray, the tiger or brown-banded snake, Hoplocephalus curtus - venomous by JS Bray, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (c004220010 / PXA 192)

Drawn from life by JS Bray, the tiger or brown-banded snake, Hoplocephalus curtus - venomous by JS Bray, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (c004220010 / PXA 192)

The first entry to be published on the Dictionary since our recent move to the new platform at the State Library of NSW is a fascinating look by Dr Peter Hobbins at the colourful life and work of James Samuel Bray, a prolific 19th century Sydney naturalist. This week on 2SER Breakfast, Nic spoke to Peter about Bray, his snakes and his museums of curios.

James Samuel Bray was an amateur naturalist in Sydney. He was a quirky chap, one of that string of strange but wonderful personalities that you see throughout the nineteenth century in Sydney, like John MacArthur and Henry Parkes. These men appeared to have extraordinary self confidence and often a blatant disregard of morals of the day, and would seem to press ahead and makes something of themselves. James Bray differed in that he never quite made it or lived up to his own expectations, but he nevertheless had a fascinating life.

This drawing in Bray's notebooks of condemned convicts leg irons in Brays Museum Sydney 10 August 1891 was accompanied by this information 'The Hon G Thornton who viewed the original specimen of these heavy convict leg irons (only used on convicts when condemned to death in the early times of New South Wales) assured me that he had frequently seen several of the men with such irons on them' Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXA 188)

This drawing in Bray's notebooks of condemned convicts leg irons in Brays Museum Sydney 10 August 1891 was accompanied by this information 'The Hon G Thornton who viewed the original specimen of these heavy convict leg irons (only used on convicts when condemned to death in the early times of New South Wales) assured me that he had frequently seen several of the men with such irons on them' Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXA 188)

Bray was born in Sydney in 1849 as New South Wales was about to be transformed by the gold rushes. This period saw an enormous growth in population across the 1850s and 1860s and with the spread of suburbs across Sydney, an associated loss of earlier colonial culture and indigenous culture as well as local flora and fauna. His family had moved from the centre of the city to Milsons Point on the harbour's north shore when he was child, an area which at that point was still only partly developed. As a teenager Bray was fascinated not only by the natural history of Sydney, but also the city's indigenous heritage. He would go prowling around the north shore and Manly looking for wildlife (which he was more than happy to kill and stuff), for items of Aboriginal heritage and he became more and more obsessed with relics of Sydney's colonial past.

A talented natural history writer, Bray also created celebrated taxidermy displays for intercolonial exhibitions. He exhibited at Sydney's Garden Palace in 1879, and in 1874 his collection of award winning entomological specimens was displayed in the gallery of the new General Post Office building where he also worked in the Telegraph Office until 1876.

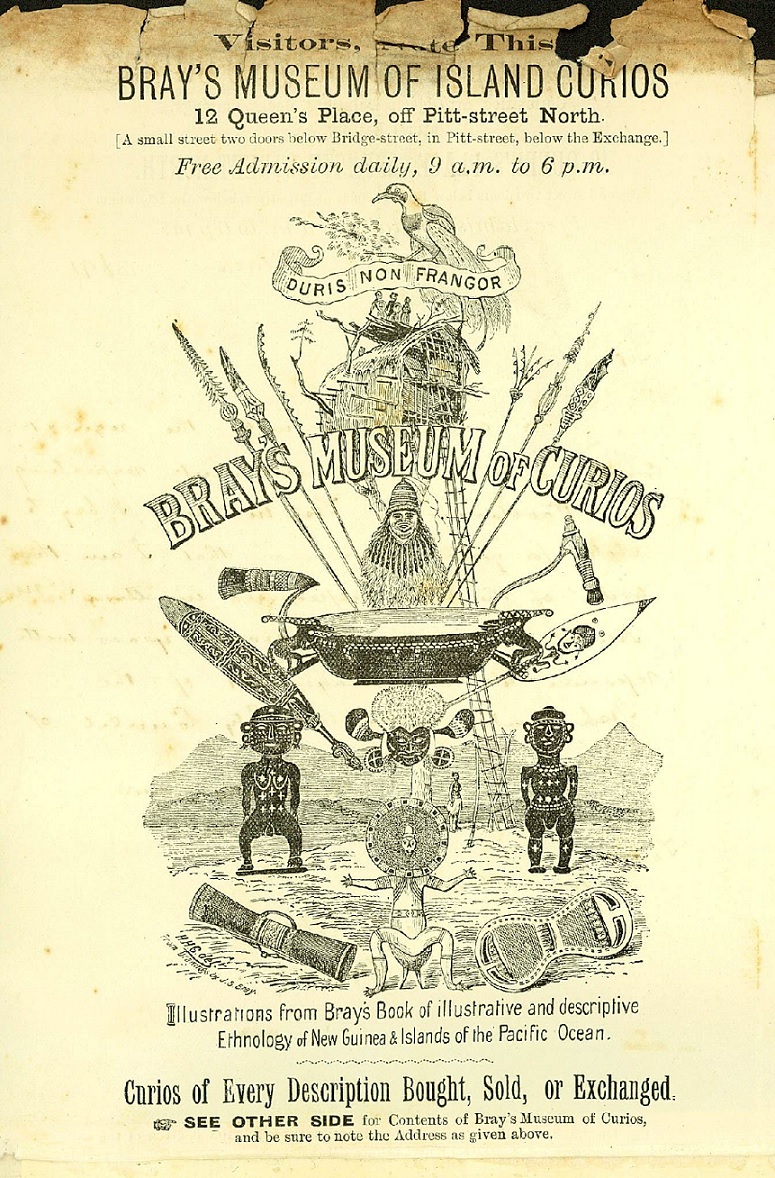

In the early 1880s, Bray established the first of his Museums of Curios, where he would sell the skulls of indigenous people from Australia & the Pacific, carved artefacts from indigenous cultures, taxidermy specimens, convict chains, coins, watercolours and almost anything in the nature of a relic he thought he could turn to account. This business failed quickly, but by the late 1880s he had opened up again near Circular Quay. When this business also failed in 1892, he began trading out of his home at 100 Forbes Woolloomooloo, where he also continued breeding snakes. Rather than just being an entrepreneur, Bray craved scientific respectability but this was never to be. His work, much like his business models, belonged to an earlier time and had fallen out of fashion.

Flyer for Bray's Museum of Island Curios c1891 Courtesy City of Sydney Archives (26/248/408)

Flyer for Bray's Museum of Island Curios c1891 Courtesy City of Sydney Archives (26/248/408)

His fascination with Sydney's flora, fauna and particularly snakes can be seen in his papers at the State Library where he extensively documents his activities and research. He loved going out into the bush and catching snakes, and describes how he'd go about this. He designed and built a snake house in the backyard of his home in Woolloomooloo, carefully considering how best to keep the snakes in his care warm and safe. He was perhaps more interested in snakes than anybody else in the colony at that time.

Although he never earned the scientific acclaim he craved, and after his death in 1916 was soon forgotten, James Samuel Bray nevertheless embodied a sense of aspiration common to many late-Victorian colonists. If he failed to capitalise on their curiosity, his Museum of Curios captured something of the growing concern that sprawling modernity entailed irredeemable losses of Australia's natural and cultural heritage.

You can read Peter's entry about James Bray and find out more about his life on the Dictionary here https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/bray_james_samuel

We're right in the middle of History Week 2017 and there are still so many great events to get to - for the full program and to find out what's on in your local area, go to the History Council of NSW website here. http://historycouncilnsw.org.au/history-week/ Happy History Week!

The Dictionary of Sydney is proud to support History Week 2017 as a Cultural Partner of the History Council of NSW

Peter Hobbins is an historian of science, technology and medicine at the University of Sydney. Much of his work has explored the meanings and boundaries of 'scientific medicine', in both nineteenth- and twentieth-century Australia. He is the author of a book on snakes and snakebite in colonial Australia, and co-author with Ursula K Frederick and Anne Clarke of 'Stories from the Sandstone: Quarantine inscriptions from Australia's immigrant past', which this week won the 2017 NSW Community and Regional History Prize at the Premier's History Awards. In 2016 Peter was the Merewether Fellow at the State Library of New South Wales, researching Sydney-based amateur naturalist, James Samuel Bray. He has appeared on 2SER for the DIctionary in a voluntary capacity.

Peter Hobbins is an historian of science, technology and medicine at the University of Sydney. Much of his work has explored the meanings and boundaries of 'scientific medicine', in both nineteenth- and twentieth-century Australia. He is the author of a book on snakes and snakebite in colonial Australia, and co-author with Ursula K Frederick and Anne Clarke of 'Stories from the Sandstone: Quarantine inscriptions from Australia's immigrant past', which this week won the 2017 NSW Community and Regional History Prize at the Premier's History Awards. In 2016 Peter was the Merewether Fellow at the State Library of New South Wales, researching Sydney-based amateur naturalist, James Samuel Bray. He has appeared on 2SER for the DIctionary in a voluntary capacity.

Listen to the podcast with Peter & Nic here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Nic Healey on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15-8:20am to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

The Dictionary of Sydney needs your help. Make a donation to the Dictionary of Sydney and claim a tax deduction!

Mozart and The Doll

Performance of 'Summer of the Seventeenth Doll',1956 With a background of 17 inch cupid dolls, each representing a season of happiness, Olive Leech (June Jago) tries to stop the fatal quarrel between her lover, Roo Webster (Lloyd Berrell) and Barney Ibbot (Ray Lawler) Courtesy National Archives of Australia (A1805, CU226/2)

Performance of 'Summer of the Seventeenth Doll',1956 With a background of 17 inch cupid dolls, each representing a season of happiness, Olive Leech (June Jago) tries to stop the fatal quarrel between her lover, Roo Webster (Lloyd Berrell) and Barney Ibbot (Ray Lawler) Courtesy National Archives of Australia (A1805, CU226/2)

The Australian Women's Weekly, 25 January 1956, p20 via Trove

The Australian Women's Weekly, 25 January 1956, p20 via Trove

The Dictionary of Sydney is proud to support History Week 2017 as a Cultural Partner of the History Council of NSW

The Dictionary of Sydney needs your help. Make a donation to the Dictionary of Sydney and claim a tax deduction!

Let's celebrate History Week 2017!

The Australian woman's mirror, October 18 1938 via Trove

The Australian woman's mirror, October 18 1938 via Trove

The Dictionary of Sydney is proud to support History Week 2017 as a Cultural Partner of the History Council of NSW

Nicole Cama is a professional historian, writer and curator, and the Executive Officer of the History Council of NSW.

She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity.

Listen to the podcast with Nicole & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Nic Healey on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15-8:20am to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney. Tune in next week to hear Dictionary of Sydney special guest Professor Richard Waterhouse.

The Dictionary of Sydney is proud to support History Week 2017 as a Cultural Partner of the History Council of NSW

Nicole Cama is a professional historian, writer and curator, and the Executive Officer of the History Council of NSW.

She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity.

Listen to the podcast with Nicole & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Nic Healey on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15-8:20am to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney. Tune in next week to hear Dictionary of Sydney special guest Professor Richard Waterhouse.

The Dictionary of Sydney needs your help. Make a donation to the Dictionary of Sydney and claim a tax deduction!

The melancholy wreck of the Dunbar

Wreck of Dunbar, South Head c1862-1863, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (a939035 / PXA 1983, f.34)

Wreck of Dunbar, South Head c1862-1863, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (a939035 / PXA 1983, f.34)

James Johnson, survivor of the wreck of the Dunbar, 1857 by TS Glaister, courtesy Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (a128698 / DG 300)

James Johnson, survivor of the wreck of the Dunbar, 1857 by TS Glaister, courtesy Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (a128698 / DG 300)

'The Sailor Rescued' or ' The rescue of the survivor, Johnson' engraved by WG Mason from a sketch by GF Angas, in 'A Narrative of the melancholy wreck of the "Dunbar", merchant ship, on the south head of Port Jackson, August 20th, 1857' 1857

'The Sailor Rescued' or ' The rescue of the survivor, Johnson' engraved by WG Mason from a sketch by GF Angas, in 'A Narrative of the melancholy wreck of the "Dunbar", merchant ship, on the south head of Port Jackson, August 20th, 1857' 1857

The Dictionary of Sydney needs your help. Make a donation to the Dictionary of Sydney and claim a tax deduction!

History Week 2017: Pop! 2-10 September 2017

The Annual History Lecture: The Popular is Political: struggles over national culture in 1970s Australia

Each year as part of History Week, the History Council present the popular Annual History Lecture.

This year the lecture will be delivered by Associate Professor Michelle Arrow, Macquarie University. You can find out more on the History Council of NSW website here.

The Annual History Lecture: The Popular is Political: struggles over national culture in 1970s Australia

Each year as part of History Week, the History Council present the popular Annual History Lecture.

This year the lecture will be delivered by Associate Professor Michelle Arrow, Macquarie University. You can find out more on the History Council of NSW website here.