The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Bricks

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Bricks

[media]On a clear day you can see forever. Well, not quite, but if you happen to be sitting in a window seat in the final minutes before the plane touches down at Sydney Airport, you can't help but notice mile after mile of brick-built houses with terracotta-tiled roofs. It's a familiar and reassuring sight for the returning traveller.

[media]Brick and clay have shaped Sydney's built environment more than any other materials. Those who dispute the pre-eminence of brick might remind themselves of the gravestone epitaph of Sir Christopher Wren. 'Reader, if you seek his monument, look around you.' All of Wren's buildings used brick, and this invitation to open one's eyes applies equally to Sydneysiders who ponder the city's forgotten and unknown brickmakers and the buildings they left behind.

[media]Most towns and cities have their fair share of brick and tile. Sydney is unusual, however, in the extent to which the urban landscape has been so profoundly influenced by these basic, yet ancient types of building materials. Although building styles have changed dramatically over the past two decades, brick and mortar remains dominant in housing construction. Yet this was not always the case. To gain a sense of place and context, we must revisit the early days of the fledgling colony of New South Wales.

The first buildings

In the weeks following the arrival of the First Fleet in January 1788, the task of establishing what was, in reality, a vast open prison soon ran up against a serious housing shortage. Canvas tents were brought ashore to accommodate convicts, the soldiery, officers and stores, but they offered little protection against the frequent thunderstorms and blinding heat characteristic of Sydney's summer months. The original residence of Governor Arthur Phillip was a framed oilcloth house which he had purchased for £125 from the London manufacturer Smith & Baber. Local timber, mostly cabbage palm, was readily available and put to use in constructing more permanent dwellings, but within months the buildings were falling apart. Unseasoned and of poor quality, the timber of the humble cabbage palm was quite unsuited to the task and its tendency to warp, twist and rot soon became apparent. Daubed with clay and painted white, they might inspire today's sentimentalists, but the reality for those housed within was grim. David Collins, judge-advocate and secretary to the colony, remarked:

slight and temporary; every shower of rain washed a portion of the clay from between the interstices of the cabbage-tree … their covering was never tight; their size was small and inconvenient. [1]

[media]Governor Phillip, a man of progressive views, envisaged durable buildings of quality and believed that in time, like any civilised town, Sydney Cove and its environs would be built in brick. Even before the Fleet's departure from Portsmouth, Phillip had anticipated the adoption of brick as a construction material. Indeed, the cargo manifest of the transport Scarborough carries a reference to 5,000 bricks. That was enough to construct solid foundations and walls for a small number of government buildings. Wooden brick moulds to form the clay into unbaked bricks were also stowed in the holds, although for reasons that remain unclear just about every type of building tool was lacking. Phillip's first request to London for stores included house-axes, carpenters' axes, pitsaws, set-saws and crosscut saws, files, augers, nails, paint and lead. [2]

James Bloodworth, first brickmaker

[media]It also seems strange that Phillip could find only one man skilled in brickmaking. This was James Bloodworth, a London bricklayer and builder whose career had come to an end almost three years earlier following his conviction for forgery. Fortunately, several other men were identified as having brick-related occupations. But still to be unearthed were deposits of workable clay necessary for the manufacture of bricks. A chance discovery was made when Phillip, who was anxious to supplement the colony's dwindling rations, set convicts to work clearing land for cultivation. One group reported plentiful deposits of fine white clay about two kilometres from the settlement, in what is now Sydney's Chinatown. Bloodworth himself may have been present at the time of the discovery. With evident satisfaction, George Worgan, the 30-year-old surgeon of the Sirius, recorded in his diary on 28 February 1788:

Our other acquisition is the lighting on a soil which is seemingly fitted for making bricks, and eight or ten convicts of the trade are now employed in the business. [3]

[media]Bloodworth was quick to grasp the importance of the clay finds along Cockle Creek and was instrumental in establishing two of Australia's oldest industries, quarrying and brickmaking. Before the year was out, the more easily-won clay deposits gave out, obliging these early brickmakers to move further up the slope. Their path always followed the streams, one of which flowed across present day George Street, just below Goulburn Street. The public brickworks of Brickfield Hill (a Sydney postal address until the introduction of postcodes in 1967) eventually comprised the upper part of what used to be known as Paddy's Markets, bounded by George, Campbell, Elizabeth and Goulburn streets. [media]The map Plan de la Ville de Sydney , drawn by a visiting French artist, Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, in November 1802, shows the Village de Brickfield and its Briqueterie (brickworks) in this vicinity.

Bloodworth was more than just a brickmaker, and quickly established a reputation as a builder of some note. Within months of arriving in the colony, he was asked to construct an official residence for Governor Phillip. It seems likely that he had some influence on the design, although responsibility was attributed to Lieutenant William Dawes, who probably objected to sharing the credit with a convict, however capable and respected. In 1797 Governor Phillip granted a pardon to Bloodworth, who won further recognition in 1801 when he was appointed supervisor of all brickmakers and bricklayers in the settlement. [media]The work of Bloodworth and others running the small private yards that could now be found in and around Woolloomooloo and Darlinghurst was so successful that within three decades Sydney's skyline came to be dominated by impressive houses commissioned by successful emancipists, gentlemen, merchants and traders representing the town's expanding commercial base. For them, a brick residence provided social cachet and ideal business premises from which they could maintain strict control over their affairs.

The move from Brickfield Hill

[media]Unfortunately, the good fortune that accompanied the building boom and the growth in private brickmaking was dealt a serious blow with the closure of the government and private yards at Brickfield Hill. For more than 40 years they had provided most of Sydney's bricks, but by 1840 their presence was a hindrance to the rapidly growing metropolis. Industry and residential dwellings made uneasy neighbours, especially at a time when town planning was almost entirely lacking. There was hardly a single tree in Hyde Park, and the bare ground increased the intensity of violent windstorms – the 'brickfielders' – which swept up grit and dust in enormous volume. Quite apart from brickfielders and polluting kilns, Brickfield Hill and its hinterland were noted for crime, which was just as bad in 1840 as it had been earlier in the century. The historian Geoffrey Scott refers to statements made by an elderly colonist at the turn of the twentieth century. The old man recalled that when he arrived in Sydney in 1838 barbaric sports still flourished around the pubs in Brickfield Hill.

'Horse racing, dog fighting, cock fighting, rat killing and prize fighting were all the rage', he related with a sort of nostalgic gusto. 'Scarcely anything else was thought of, and it was very hard for a young fellow to settle down and become steady'. In one Brickfield Hill tavern he saw two bulldogs fight, and when they had sunk their teeth into each other 'the owner of one dog chopped off two of his feet to show the breed of the dog that still kept on fighting!' [4]

[media]Such activities were considered perfectly normal ways for working men to indulge their passion for beer, a bet and some biff. Responding to complaints, the government stepped in, conscious of its responsibility to clean up areas that attracted such activity and the criminal behaviour that often came with it. Towards the end of 1841 it ordered the cessation of brickmaking on Brickfield Hill, which had disastrous consequences for many people involved in the trade. One suspects the closure had less to do with cruelty to animals than it did with the merchants and well-to-do whose mansions and townhouses shared the same backyard as the industrial workings of Brickfield Hill, a 10-minute stroll from Hyde Park.

New brickmaking areas emerge

In [media]the absence of alternative sites, and with the continuing high demand for bricks, the industry found itself in a crisis that took several years to resolve. Where did brickmakers ejected from the brickfields go? Slowly they moved to Balmain, Glebe, Newtown, Redfern, Alexandria, Marrickville, St Peters, Camperdown and Waterloo, where new clay deposits and timber for firing were present. Yards in many of these emerging suburbs were already being worked, often loosely organised as family firms that may have employed five or six people at most, with a proportionately small output.

Some manufacturers moved to land that is now occupied by the Broadway shopping centre. Good quality clay and fresh water were paramount considerations and could be found on the western edges of Cockle Bay. Further down the road to Parramatta, in Camperdown, was another location that offered plentiful supplies of clay and fresh water. Johnstons Creek, which rose in Stanmore and discharged into Rozelle Bay, along the way taking in groundwater and streams draining from the higher ground, was an invitation for others to establish brickworkings. The districts of Leichhardt and Ashfield, with their surface clays and underlying bands of shale which were to prove a boon later in the century, were also prime locations for brickmakers. Sufficiently far from Sydney to prevent the smoke haze created by the firing of bricks from being a serious nuisance, yet close enough to supply the metropolitan trade and local builders, the yards went about their business unchallenged.

St Peters brickyards

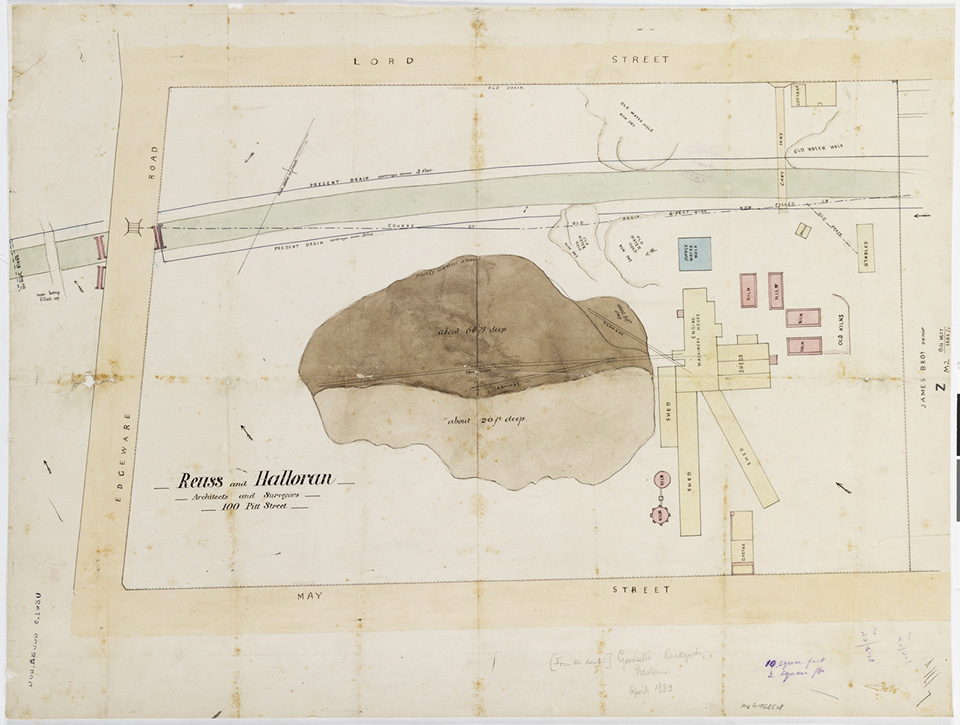

By far the most [media]important development for some of the dispossessed was the move to St Peters, a delightful country idyll along the track that led through and beyond the hamlet of New Town. St Peters and its newly-built church lay atop the sloping escarpment that runs down to Sheas Creek, a tributary of the Cooks River, later made into the Alexandra Canal. It was here that some of the finest clays were to be had, and in great [media]abundance.

St Peters and its environs were already well-established as home to wealthy landowners. Lilith Norman, in her short work Historical Notes on Newtown, remarks:

Passing the site of the present Newtown Bridge, the road turned due south and continued out to St Peters and Cooks River. This district was the home of many of the early élite of Sydney. Dr Wardell had a large estate at Cook's River which, after his murder by a convict, was divided into three properties. One of these was owned by a Mr Mace, and was later purchased by Thomas Holt, one of Sydney's wealthiest businessmen. Other properties included the Unwin Estate and AB Sparkes' fine old home, Tempe. [5]

[media]The lands across the road from the church, including those much later enclosed by Sydney Park, eventually became home to prominent brickyards established during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The landmark chimneys of the former Bedford Brick Works and the kilns, a Hardy Patent and Hoffman type, with three downdraught (dome) kilns, are the only reminders in 2008 that an industry of great importance once stretched from this point down to Smith Street at Tempe.

A cornucopia of brick and tile manufactories! Among them were the Bedford Brick Works, the Warren Brick Company, the Carrington Brick Company, St Peters Brick Company and the City Brick Company. In time all of these firms came to be owned by another local firm, the Austral Brick Company, which operated further down the road on land that stretched from the junction of Canal Road and Princes Highway (formerly Cooks River Road) to Cowper Street.

Just a stone's throw from Campbell Road, which forms the southern boundary of Sydney Park, was the yard of the Central Brick and Tile Company, a significant manufacturer and local employer. Next door are the defunct yards of Austral Bricks and its enormous clay and shale pits, which in 2008 are used as a vast rubbish dump and waste transfer station. On the site once occupied by the brick kilns and machine shops, various shops have taken up residence. And is that the remains of the company's solid brick wall that fronts the street? [media]Former employees of the many yards mentioned above referred to this huge swathe of land as the 'Golden Mile', an invention of the men who toiled in the yards during the middle decades of the twentieth century. Brickworkings were also established on the other side of Cooks River Road, in and around Marrickville.

Industrial development at St Peters

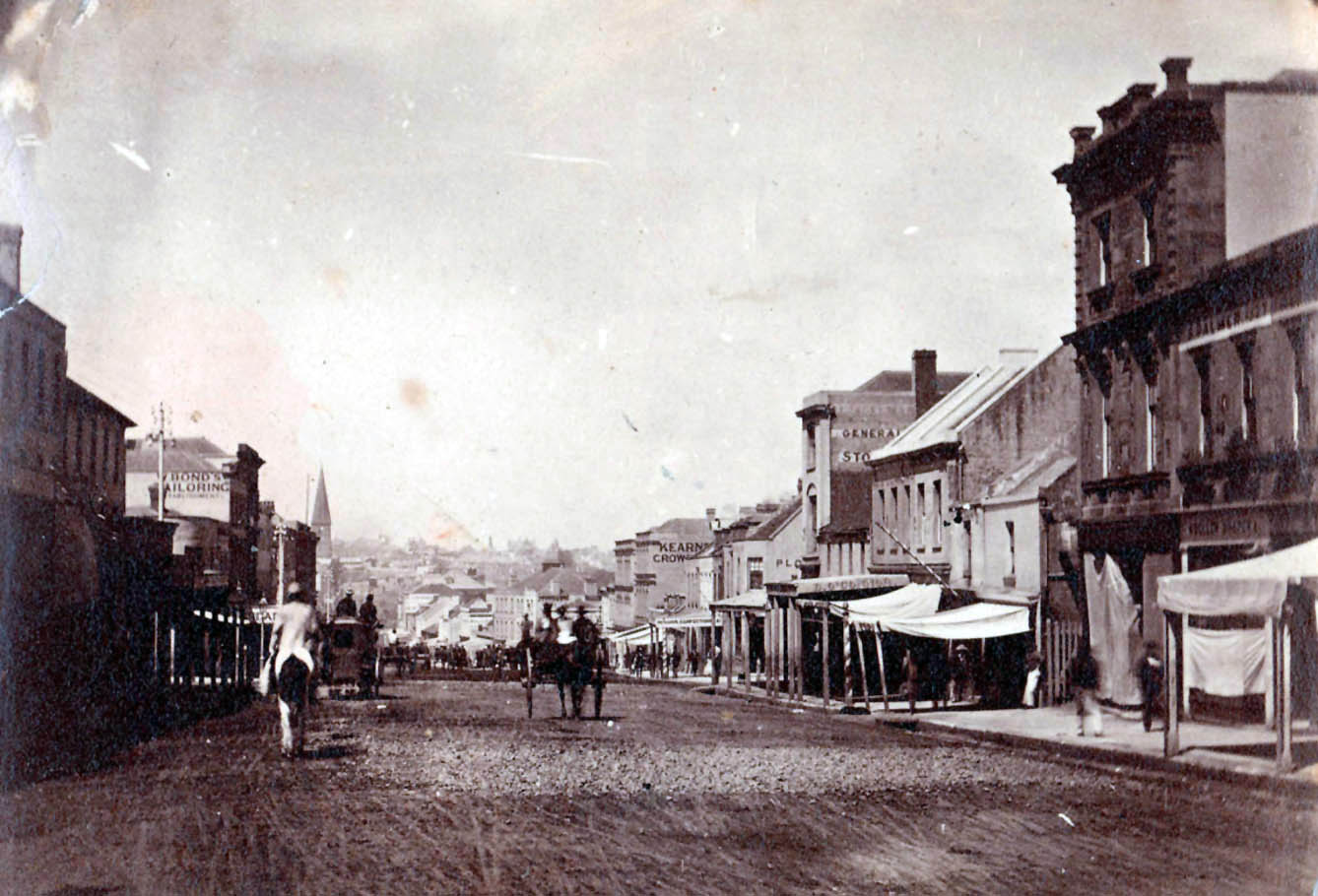

[media]In the early 1840s there was little to suggest that the area was about to be transformed into an industrial conurbation. As brickmasters trundled their families and chattels along New Town's King Street in search of the new El Dorado, the only indicators of industry was the presence of tanneries and leatherworks on the banks of Sheas Creek. Tanning, however, was a cottage industry rather than a major industrial enterprise. Brickmaking was different, and arguably constitutes the first wave of substantial industrial activity in Sydney. [media]Certainly, with the establishment of yards on land acquired as a result of the subdivision known as the Needham Estate, and the close proximity to markets, the conditions for rapid development and industrial organisation on a larger scale were present.

Beneath the thin layer of surface clays, these early pioneers soon discovered deep bands of prime, brick-making shales belonging to the Wianamatta group, the brickmakers' equivalent of gold. [media]Shale, which has the appearance of slate, must be crushed and ground into dirt before it can be pressed into bricks. The process requires heavy investment in plant and machinery, which had grave implications for family operations well before the end of the nineteenth century.

For the more prosperous and entrepreneurial brickmakers of the St Peters–Marrickville–Tempe district, it was only towards the end of the nineteenth century, with the formation of limited liability companies, that sufficient investment capital enabled production units to become large enough to meet the demand. Unsurprisingly, many family businesses failed, and ownership of brick firms was gradually concentrated into the hands of relatively few companies. The transition, which took nearly a century, was spurred by short-term fluctuations in the trade cycle, and catastrophic depressions (1840s, 1890s, and 1930s).

More than a century passed before houses again encroached on the brickfields and their fire and smoke-belching kilns, bringing issues of pollution to a head once more. For many residents, the end could not come soon enough. The last bricks were burnt in the main Austral yard opposite St Peters church in May 1983.

Sydney's remaining brick industry

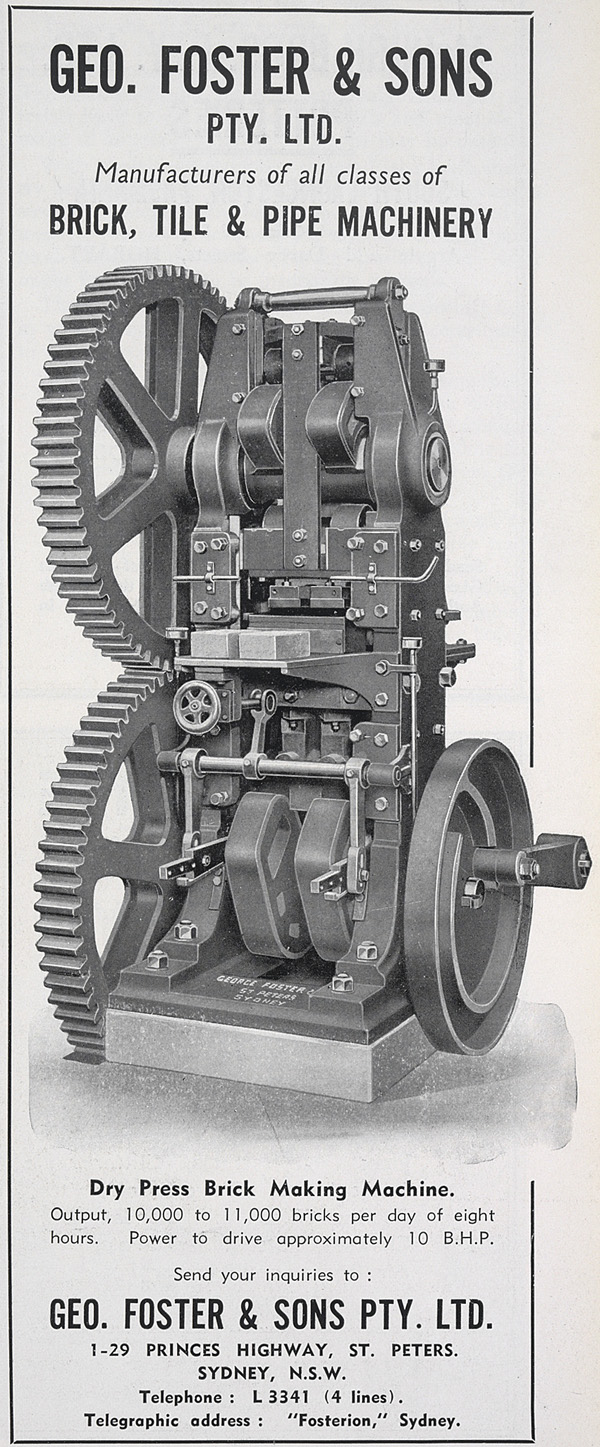

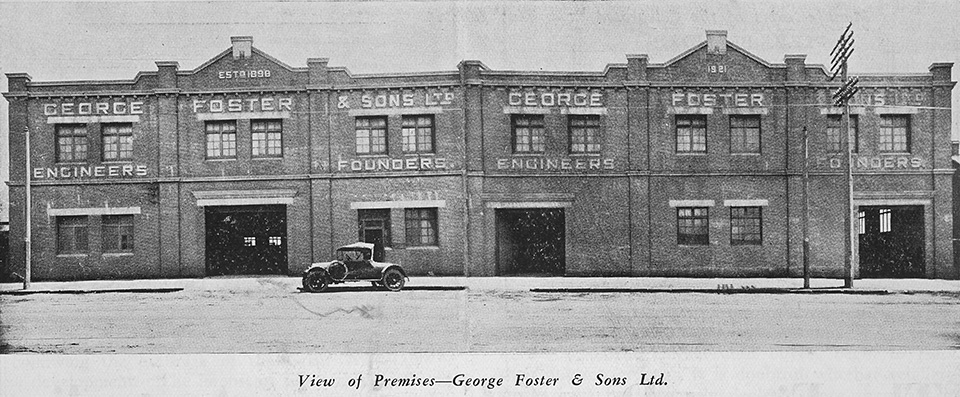

[media]The demise of brickmaking at St Peters meant the end of the industry in the area, and with it the gradual disappearance of satellite industries such as foundries, engineering works, brick carters and pubs. One hundred and fifty years of social and economic history is difficult to erase, and, despite the gradual gentrification of the area, kinship and community ties are still very much alive.

[media]Elsewhere in Sydney, traditional dry press brickmaking by the Austral Brick Company continued at Eastwood for another two decades and at Brookvale for at least 10 more years. Brickmaking at Ashfield and other yards in various parts of the city, including Thornleigh and Artarmon, had ceased in the early 1970s. Yet this did not spell the end of Sydney's brick industry. Long before 1983 modern extrusion plants with their tunnel kilns had been established in the western suburbs by Austral Bricks and its competitors, the State Brick Works (which operated at Homebush until the early 1980s) and PGH.

References

Ron Ringer, The Brickmasters, 1788–2008, Dry Press Publishing, Sydney, 2008

Notes

[1] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, T Cadell Junior and W Davies, London, 1798, vol 1, pp 19, 71

[2] Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, vol 1, p 308

[3] George Worgan, Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon, cited in Jack Egan, Buried Alive, Sydney 1788–92: Eyewitness accounts of the making of a nation, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1999, p 37

[4] Geoffrey Scott, Sydney's Highways of History, Georgian House, Melbourne, 1958, pp 49–52

[5] Lilith Norman, Historical Notes on Newtown, Council of the City of Sydney, Sydney, 1963, p 7

.