The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Gnung-a Gnung-a Murremurgan

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Gnung-a Gnung-a Murremurgan

[media]It is 200 years since the death of an adventurous young Aboriginal Australian who crossed the vast Pacific Ocean to North America and returned to Sydney. From the deck of an English storeship he glimpsed many strange places, visiting Norfolk Island, Hawaii, Nootka Sound (now Vancouver, Canada) and the Spanish colonies of San Francisco, Santa Barbara and San Diego on the Californian coast.

The voyager was Gnung-a Gnung-a Murremurgan, whose wife Warreeweer was the younger sister of the Wangal leader Woollarawarre Bennelong, at that time being feted in London society. The distance Gnung-a Gnung-a traversed was some 16,000 miles (25,750 kilometres) as the crow flies, but much further in a sailing ship driven by unpredictable winds.

On the first day he ventured into the convict settlement at Sydney Cove, in November 1790, Gnung-a Gnung-a adopted the name 'Collins' from Acting Judge Advocate David Collins, who often mentions him in An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, published in London in 1798.

It was the idea of Major Francis Grose, acting governor of New South Wales after the departure of Captain Arthur Phillip in 1792, to embark 'a native of this country' on HM storeship Daedalus 'for the purpose of acquiring our language', wrote David Collins. The 350-ton capacity vessel was ordered to resupply provisions for the expedition to the north-west coast of North America commanded by Captain George Vancouver (1757–1798). In the navy ships HMS Discovery and HMS Chatham, Captain Vancouver was to complete the survey made by Captain James Cook.

Voyage to America

HMS Daedalus sailed from Port Jackson on 1 July 1793, passing west of the Society Islands (French Polynesia) to Owhyee (Hawaii). The commander, Lieutenant James Hanson, missed a rendezvous with Vancouver's ships at Nootka Sound on 8 October, but anchored with the two survey ships off San Francisco Bay on 21 October. The three British ships followed the coast of today's California to San Diego, leaving on 9 December 1793 and arriving at Hilo in Hawaii on 8 January 1794.

The Hawaiian King Kamehameha, who warmly welcomed Vancouver, was so impressed by the good-natured, handsome Aboriginal man on the expedition that he wanted to buy him, offering in exchange canoes, weapons and curiosities.

Gnung-a Gnung-a got on well with everyone on Daedalus and Hanson was pleased by his good nature and his willingness to do whatever was asked of him. During his month in Hawaii, he often went ashore with his shipmates. 'Wherever he went he readily adopted the manners of those around him', Hanson later told Collins, who remarked, with ironic humour, that

when at Owhyee, having discovered that favours from the females were to be procured at the easy exchange for a looking-glass, a nail, or a knife, he was not backward in presenting his little offering, and was as well received as any of the white people in the ship. It was noticed too that he always displayed some taste in selecting the object of his attentions. [1]

Return to Sydney

Home in Sydney Town, Gnung-a Gnung-a fought and wounded 'a very fine young fellow' called Wyatt, who had taken up with his wife during his absence and Warreeweer 'became the prize of the victor'.

During a ritual revenge combat in December 1795, Pemulwuy, leader of the Georges River Bidjigal near Botany Bay, launched a spear at Gnung-a Gnung-a that remained fixed in his back. The English surgeons could not extract the spear and thought he was unlikely to recover. Gnung-a Gnung-a, however, left the hospital and walked about for several weeks with the spear protruding from his back. 'At last,' wrote Collins in a footnote,

we heard that his wife, or one of his male friends, had fixed their teeth in the wood and drawn it out after which he recovered, and was able again to go into the field. His wife War-re-weer showed by an uncommon attention her great attachment to him. [2]

Before this unexpected recovery, David Collins wrote a brief appreciation of his namesake:

He was much esteemed by every white man who knew him, as well on account of his personal bravery, of which we had witnessed many distinguishing proofs, as on account of a gentleness of manners which strongly marked his disposition, and shaded off the harsher lines that his uncivilised life now and then forced into the fore-ground. [3]

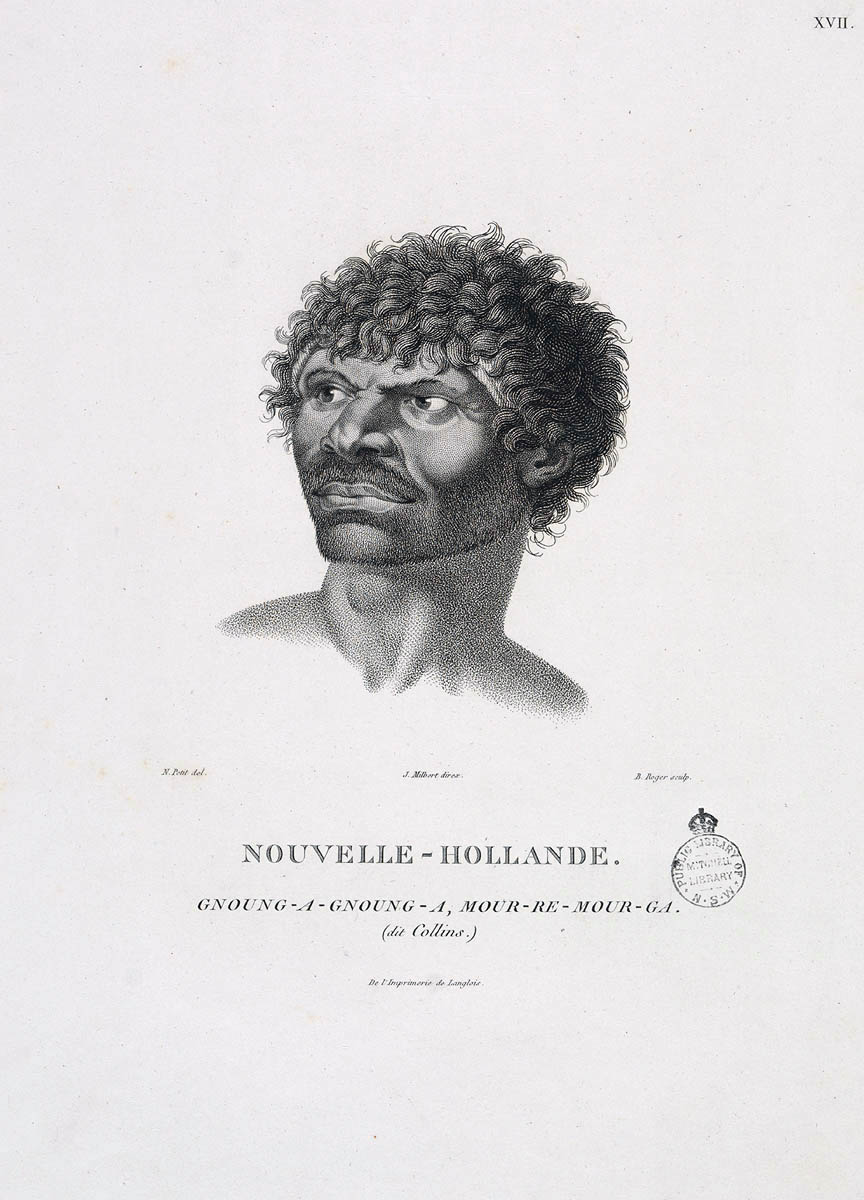

While in Sydney with a scientific expedition commanded by Nicholas Baudin in 1802, the young French artist Nicolas-Martin Petit met Gnung-a Gnung-a and sketched a striking portrait that he captioned 'Gnoung-a gnoung-a, mour-re-mour-ga (dit Collins)'

A report in the Sydney Gazette of Sunday 15 January 1809 said that the body of 'Collins' (Gnung-a Gnung-a Murremurgan) had been found beside the Dry Store, site of the present Sirius Park in Bridge Street, Sydney. The newspaper said he had been known for 'the docility of his temper, and the high estimation in which he was universally held among the native tribes'.

On the night of Thursday 12 January 1809, Gnung-a Gnung-a's children, others he had adopted, and his brother Old Phillip, faced a salvo of spears in the ritual ordeal that followed death in Aboriginal society. The date of his death was not recorded, but it was customary to keep an overnight vigil over a dead body before burial and the subsequent revenge combat, so it was probably 11 January.

Gnung-a Gnung-a Murremurgan is one of many Aboriginal men and women who sailed from Sydney in English ships and played a significant role in Australia's early maritime history.

References

Mari Nawi: Aboriginal Odysseys, exhibition curated by Keith Vincent Smith, Mitchell Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, September-December 2010

David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales (1798), BH Fletcher (ed), Reed Books, Sydney, 1975

George Vancouver, A voyage of discovery to the North Pacific Ocean, and Round the World, John Stockdale, London, (1798) 1801, pp 296–364

Notes

[1] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales (1798), BH Fletcher (ed), Reed Books, Sydney, 1975, pp 302–3

[2] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales (1798), BH Fletcher (ed), Reed Books, Sydney, 1975, p 372

[3] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales (1798), BH Fletcher (ed), Reed Books, Sydney, 1975, p 372