The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Law and order

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Law and order

The [media]politics of law and order were present at the foundation of Sydney as a convict settlement. They have remained part of the fabric ever since – and a vital aspect of the city's imagined life. Like many other parts of the city (its churches, its schools, its hospitals), the institutions of law and justice are a material aspect of the values and experiences of those who inhabit the city. The courthouses, prisons, police stations and (more potently in recent decades) police cars, vans and buses are both substance and symbol of law and authority. More than other institutions, however, those of law and order allow for the play of fears, anxieties, prejudices and contempt as well as the deployment of rules, norms, standards and accountability. So the histories of law and order are stories about what happens in courts, police stations and prisons – but also on the street, in shops and boardrooms, on the beaches and in the parks, and in the homes of city dwellers. They are stories told in parliament, newspapers, books, on radio, television and film, and in conversation and song. They are stories about crime and policing, harms done and punishments handed out, corruption and evasion. They make up a crucial part of the life of a city. The stories that Sydney tells include these kinds of stories.

The search for order

The earliest decades of European settlement were dominated by a search for order in the face of numerous threats. The authority of law was asserted by military government through public punishment of convicts, free settlers and Aborigines. [media]Hanging, flogging, and even being nailed by the ear to a pillory post were instruments of punishment used in the early decades. [1]

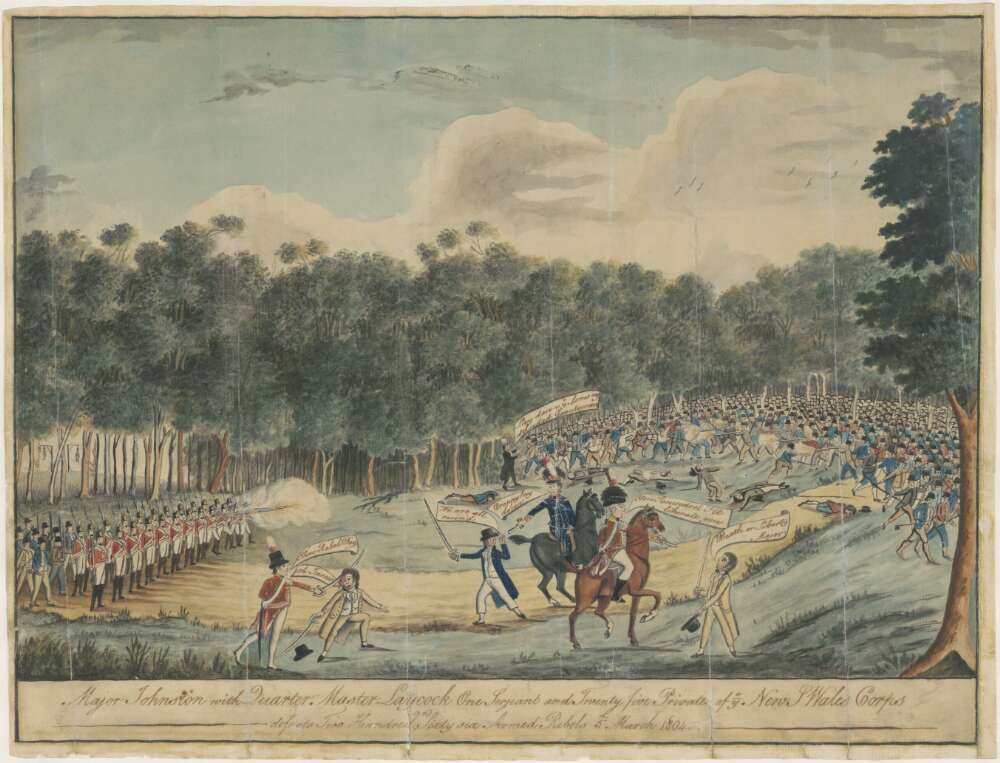

At Vinegar Hill (now Castle Hill) on the outskirts of Sydney in March 1804, rebellious convicts, most of them Irish, challenged military power with pikes and other primitive weapons. [media]The rebellion was easily but bloodily suppressed, and its leaders killed in flight or hanged in exemplary punishment. [2]

Not even the governor himself was free from personal threat and humiliation – on 26 January 1808, Governor Bligh was famously deposed in the 'Rum Rebellion', an outcome of his long-running dispute with the military elite of the New South Wales Corps.[media] The event was rare, indeed unique in its achievement; most challenges to law and order in the colonial era were less focussed on the very pinnacle of authority. [3]

In 1816, the otherwise sympathetic Governor Macquarie drew a line against Aboriginal people armed or in parties numbering more than six, excluding them from Sydney and other settlements as 'disturbers of the public peace'. [4] It wasn't to be the last time policing in Sydney was used to draw boundaries around the city's Aboriginal people. [media]Since the 1960s, as the city's Aboriginal population has grown, the inner-city suburb of Redfern has witnessed continuing conflict over the use of public space, sometimes to the point of riot. [5]

The development of 'law and order' politics

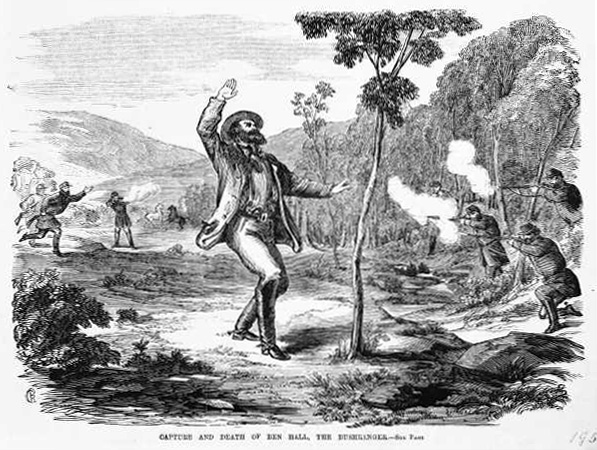

The uneven spread of settlement beyond the Sydney hinterland prompted many occasions for the development of public anxiety over the security of the archipelago of colonial towns and villages. The Sydney press was the key element in the developing public discourse about the safety and condition of society. As it grew in confidence in the 1820s and 1830s it demonstrated its independence through vigorous assertion of the rights of settlers to security in the face of hostile Aborigines, or the competing claims of emancipists to equal status in the growing colony. The urban politics of law and order had its birth in these campaigns of the pen. Long before Sydney was the home of the colonial parliament, it was the locale for the generation of law and order politics. [media]This was evident in the anxieties generated by bushranging in the 1830s or 1860s, but also in the battles around the treatment of Aboriginal people.

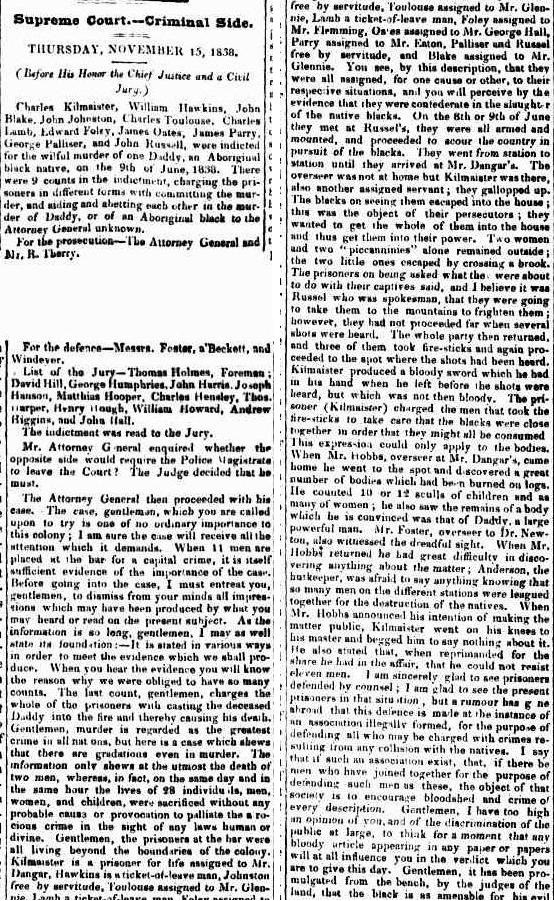

Nothing better characterises the divisive urban politics of law and order than the extraordinary events surrounding the Myall Creek massacre in the northern reaches of the colony in 1838. [media]The prosecution, and eventual hanging, of the white killers of Aboriginal people polarised opinion between populists who objected to the hanging and the advocates of a strict application of justice in defence of Aboriginal subjects of the Crown. The location of the Supreme Court in King Street, Sydney, from 1827, and the main jail and execution site in Darlinghurst from 1844, amplified the possibilities of political agitation in a way that incited both debate and hysteria. [6]

Crime in the streets

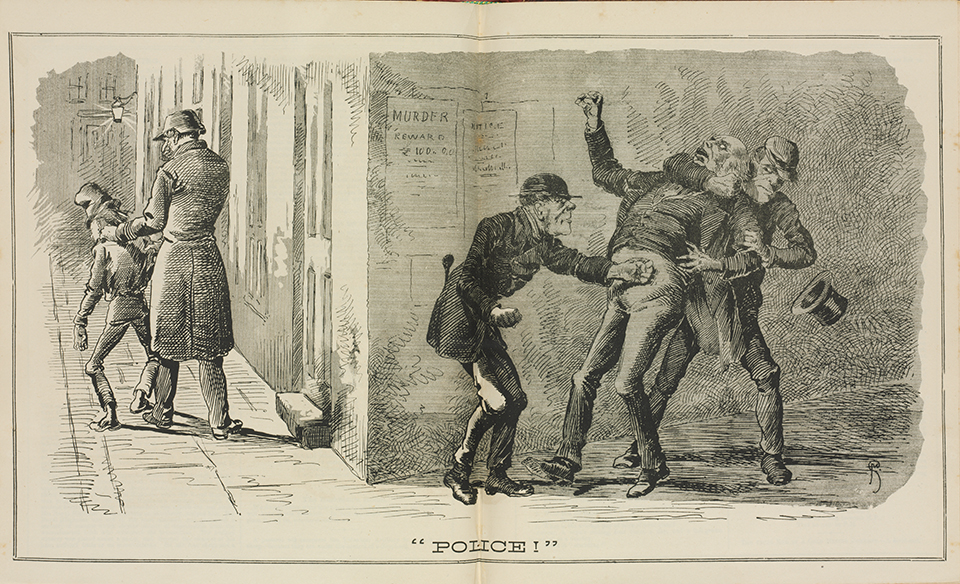

A different kind of agitation had long become a staple of public comment in the press – the condition of Sydney's streets, in particular the disorder caused by drunkenness, which was frequently linked by its critics to the vulnerability of a society dominated by a convict and emancipist population. Occasional crimes of extreme violence were seen as symptoms of a depraved society, or at least a society under continuing threat from its disproportionate share of a criminal population. In 1835, when Judge Burton of the Supreme Court deplored the number of serious crimes being brought before the courts, the Sydney Herald responded with an alarmed editorial about a crime record 'unexampled in the criminal records of any country'. A decade later the same paper worried about the 'complete sense of insecurity':

Robberies and murders, increasing both in numbers and in audacity, infest our streets and beset our inhabitations. [7]

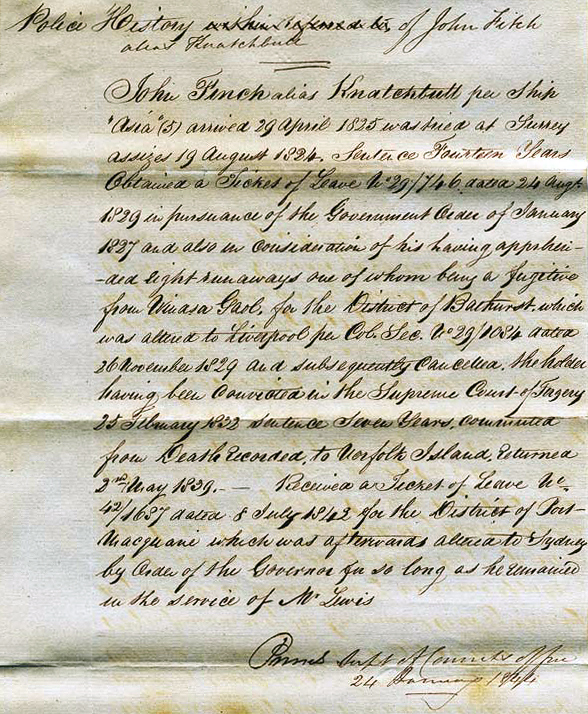

[media]In fact the city's crime rate had gone down, but highly publicised crimes, such as the murder of shopkeeper Ellen Jamieson by John Knatchbull in January 1844, combined with economic insecurity to justify a campaign to rid the city of its convict population.

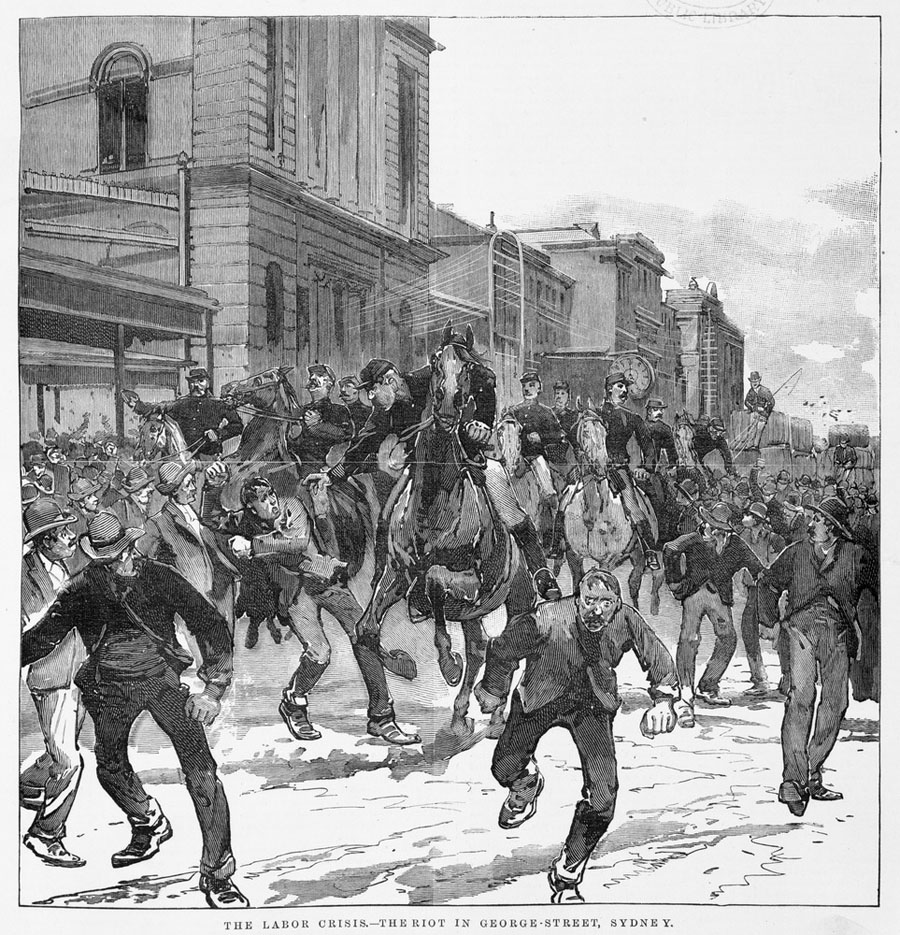

Post-convict Sydney did not avoid law and order problems and panics. In a self-governing colony, and later state, law and order were a preoccupation whenever the times were unsettled by economic downturns, rapid population movements, or major external events affecting the morale and disposition of the whole society. In the 1970s a long-term study of crime and civil disorder in Sydney identified three periods of major disorder, characterised by major protest and political ferment – the late 1880s, World War I and its aftermath to 1935, and the late 1960s. [8]

[media]All of these eras involved significant clashes between police and protesters, rioters and sometimes political extremists, such as the fascist-leaning New Guard of the 1930s or the revolutionary Wobblies (Industrial Workers of the World) who were tried for a conspiracy of arson during World War I. [9] At such times law and order concerns were manifested in demands for reform of laws, or of policing, or for harsher punishments, or even exclusion and control of minority populations. The realities of urban life – especially the large concentrations of population and a multiplicity of media – helped turn urban preoccupations into those of the state.

Celebration, youth and alcohol

The annual cycle of celebrations and events has provided generations of Sydneysiders with the spectacle of large crowds, usually of young men imbibing significant quantities of alcohol, leading to public disorder, riot and occasional violence. Summer in Sydney has always been a time with potentially disruptive consequences. These have at different times prompted political and social anxieties about law and order – the riots at Bondi Beach on Boxing Day 1884 were a symptom of the emerging larrikin menace that preoccupied Sydney's press for the following two decades. [10]

The Cronulla Beach riot and its violent aftermath over successive days in December 2005 seemed to revisit many of these elements. Fuelled by alcohol consumed over a number of hours on a hot December Sunday, a large crowd of young beachgoers, many wearing Australian flags or T-shirts with anti-migrant slogans, attacked a number of young men perceived as being of 'Middle Eastern background'. This was a populist law and order outbreak, stimulated by allegations that off-duty beach lifesavers had earlier been assaulted at the beach and made more controversial by the role of radio talk-back hosts and the use of mobile telephones. The riot and its aftermath, when Lebanese Australian youths in cars went on their own rampage at Maroubra Beach the following night, provoked widespread reaction, in the city, state and nation, about the character of Sydney and its future. Substantial police powers were invoked to control the movement of vehicles around major beaches in the following days and weeks. [11]

The Cronulla riots were unusual because they connected political and cultural beliefs and prejudices with a popular culture locale. But this was certainly not the first time the combination of youth and alcohol provoked wider anxiety about the city's social and moral fabric. Previous outbreaks of youthful drunken violence were a catalyst for important changes in urban policing. [media]In 1850 there was an outbreak of rioting in Sydney on New Year's Day, with window smashing and minor arson, not serious enough to cause injury or loss of life but alarming to the city's citizenry. Nothing more serious than 'the pure love of mischief' [12] could be discerned in the actions of the rioters who included a large number of boys. But the government responded by reforming the police and expanding the numbers of constables on Sydney streets.

One hundred years before the Cronulla riots, the exuberance of New Year's Eve crowds in Martin Place and other areas of the city prompted a major review of police powers and tactics in dealing with street drunkenness and disorder. Once again the press played a key role in amplifying anxieties over the state of the city, and the nation. [media]Under the headline 'Mob Rule' the Sydney Morning Herald deplored the rowdyism of New Year's Eve celebrations in the city and inner suburbs, claiming that

the conduct of a large proportion of the crowds is without parallel in the history of the Commonwealth.

In truth the extent of the violence and mob rule did not appear to extend beyond some resistance to police and firemen who were attempting to extinguish bonfires in Woolloomooloo and Paddington. But others worried about the evidence of a decline in moral tone, evident in embracing and kissing among the crowds – letters to the editor worried about what sort of mothers and fathers the country was breeding.

Over the following months police and legislators combined to review the powers available to police in controlling such a 'saturnalia', as the Sydney Morning Herald had called it. Police had been troubled for some years by the petty nuisance and occasionally more serious violence of the city's 'larrikins' – gangs of youths whose rowdy behaviour and flashy style were the subject of frequent comment and criticism around the end of the nineteenth century. In 1908 police succeeded in winning broader powers of arrest for offences of disorderly behaviour or the use of insulting words, powers they came to use with little accountability in Sydney's minor courts. [13]

External threats

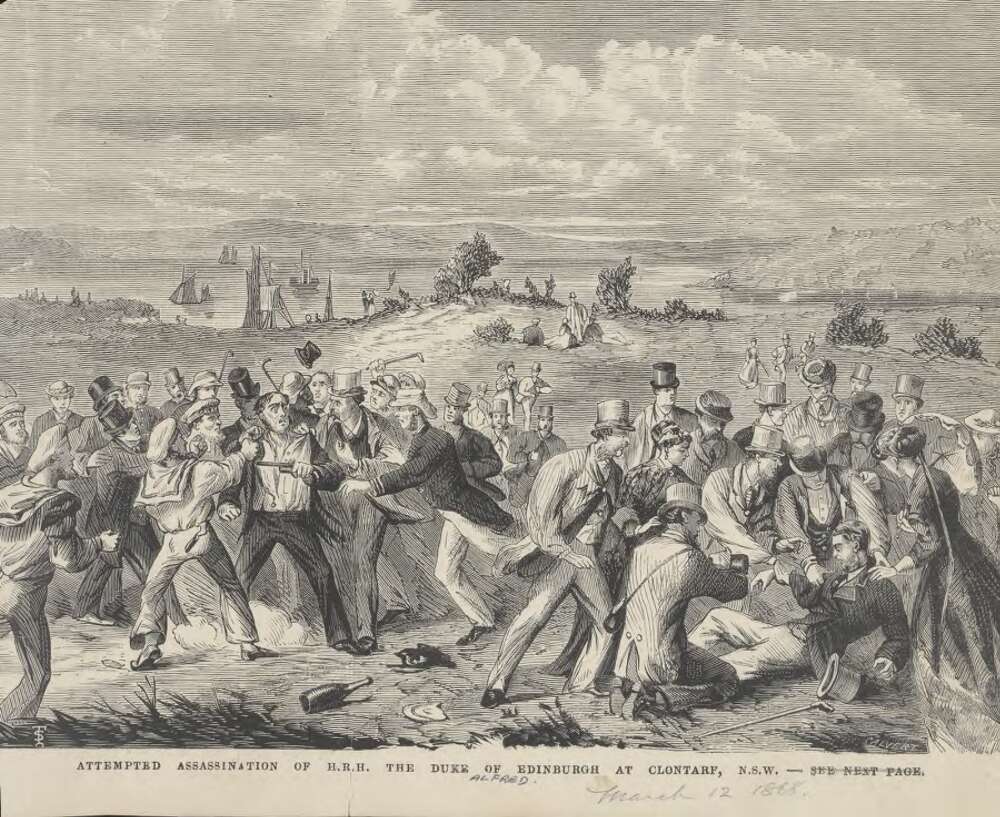

The [media]not too subtle mix of politics, alcohol, racist prejudice and cultural chauvinism evident at Cronulla was also prefigured in other historical crises of law and order in Sydney's history. In 1868 one of the most dramatic nineteenth-century challenges to established authority occurred at Clontarf when Henry James O'Farrell succeeded in shooting Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh and second son of Queen Victoria. The relative success of colonial life in mollifying sectarian sentiment threatened to founder in the events that followed. In spite of evidence that O'Farrell was insane and that no other conspirators acted with him, the New South Wales Premier Henry Parkes sought to make political capital out of the event. Once again legislation to attack a feeble threat was brought into play – with New South Wales getting its first Treason Felony Act , 1868, a statute destined for oblivion because of the minuscule nature of the threat. In this case the politics of law and order were marshalled to save a political career, with Parkes invoking the spectre of Fenianism harboured by the Irish Catholic minority. [14]

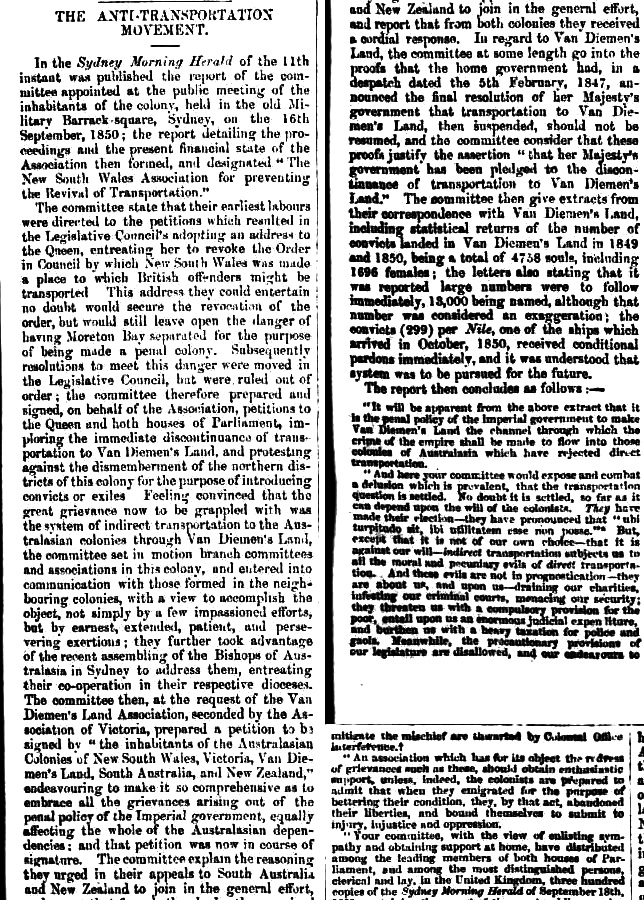

Parkes's campaign against a largely imaginary Fenian threat played off the reality of the British world of which Sydney was just a part. [media]Law and order campaigns frequently had cause in the nineteenth century to represent the British metropolis as a source of trouble to the colonial city – trouble which was best met by vigorous resistance and political exclusion. That was the case in 1849 when anti-transportation crowds, some verging on riot, protested against what the leading politician Robert Lowe described as the 'grossest outrage' – the arrival of a convict ship, the Hashemy, from Britain. [15] Similarly in 1888, a mere 59 Chinese passengers (many of them returning to a country they had already made their own) aboard the merchant ship Afghan were refused entry to Sydney, in response to a campaign organised against them by leading politicians and crowds of protesting white settlers. [16]

A vision of the desirable society lies behind such campaigns to establish or re-establish an order of things perceived as threatened – sometimes jobs, but also places, beliefs or morals. In the twentieth century, such exclusions were less the outcome of public demonstration than of determined policy in defence of White Australia: in 1916 more than 200 Maltese labourers were prevented from disembarking at Sydney after failing a dictation test under the Immigration Restriction Act, 1901, given in Dutch, in Melbourne. [17]

Police provocation

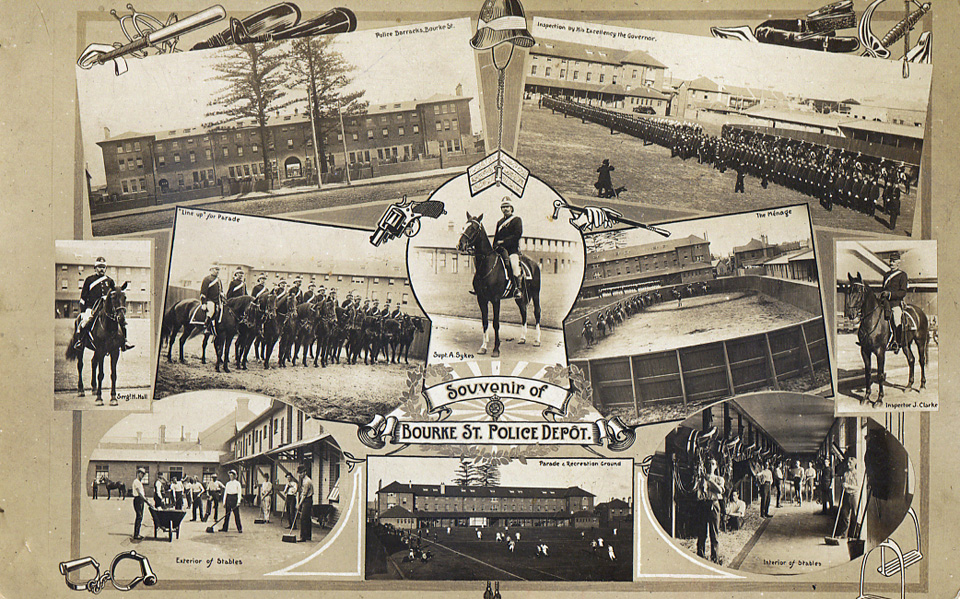

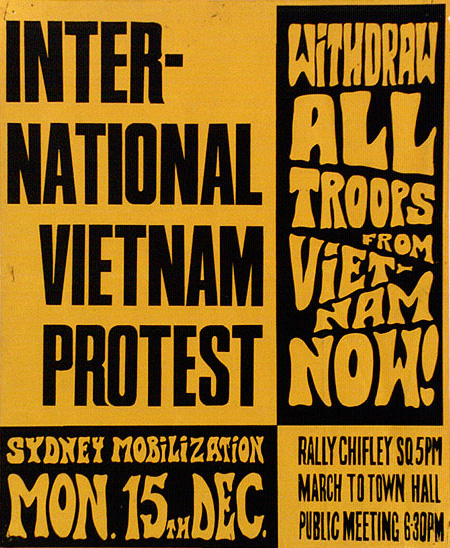

The forces of law – police above all but also judges and magistrates in their pronouncements from the bench – play a critical role in setting the boundaries of order. [media]In some generations their actions and words themselves provoked a new kind of law and order crisis – the policing of street demonstrations during the Vietnam War significantly undermined public confidence in the police. [18] The reputation of Sydney police was shattered by the harsh light of public exposure in the Royal Commission into the New South Wales Police in 1996, with its widely publicised evidence of police in Kings Cross receiving bribes.

At other times the play of power has been more sinister, because more personal, in its vision and interests. In the 1950s the activities of Sydney's Vice Squad in attempting to control homosexuality resulted in a culture of persecution through provocation, intimidation, prosecution and blackmail. [media]Much of the policing of that era – the close surveillance of public lavatories, beachside haunts and other locales suspected of harbouring homosexuals – had its inspiration in the personal dedication of the police commissioner, Colin Delaney, to eradication of what was seen as a homosexual threat. [19] The generally silent pursuit involved in such police campaigns may have played a part in inciting the later activism of Sydney's gay communities agitating for law reform and control of police powers.

Police interests

Police interest played a different kind of role in generating a new kind of 'law and order politics' in the 1960s. Once again some elements of urban cultural life were implicated – on the beaches of Sutherland Shire in the early 1960s, rival gangs of 'sharpies' and 'rockers' came to blows in repeated incidents that provoked much media comment and calls for tougher policing. In September 1963 the St George and Sutherland Shire Leader defended police against recent press allegations of bashings, pointing instead to the good and necessary work of police dealing with violent gangs:

surely we are not reaching the stage where police doing their duty are expected to make themselves defenceless punching bags and footballs for criminals and louts who want to take charge of the public streets.

Over the following two years the Sydney press endorsed the campaigns of the police union for more police – 1,000 more at first, escalating to calls for 2,000 more, during the 1965 election campaign.

Embracing the police call for greater numbers, the Liberal Party leader Robin Askin won power in the first of many elections in succeeding decades that focussed on issues of 'law and order'. Such campaigns did not always turn on the incidence or nature of crimes, but a number of shocking crimes in 1964 had helped promote the case for more police and in January 1965 two teenage girls were sexually assaulted and murdered at Wanda Beach, near Cronulla. Almost immediately the leaders of the opposition Liberal and Country parties issued a joint statement urging a major increase in police strength, to 'prevent many outrages of the type being currently committed'. They drew a lesson about government neglect:

for years the Opposition parties have pressed the Government to enlarge the Police Force to ensure the proper preservation of law and order and to guard the safety of the people, particularly women and children.

The press supported them with commentary linking the Wanda Beach murders to the lack of police. So successful was this promotion of law and order as a political football that few major political parties after this date would do anything other than seek the favourable endorsement of the local police union. [20]

The media and crime

Serious crimes test a community's values and the limits of tolerance. Homicide and rape have been part of the city's history from its beginnings, however only some events however seem to inflame the anger and desire for retribution that threaten the consensus on legal process and just punishment. The city's media have played the critical role in elevating such events into stories that become part of Sydney's history, or at least the side of it that manifests anxieties and fears about the vulnerability of the innocent and the threat of the dangerous. [21]

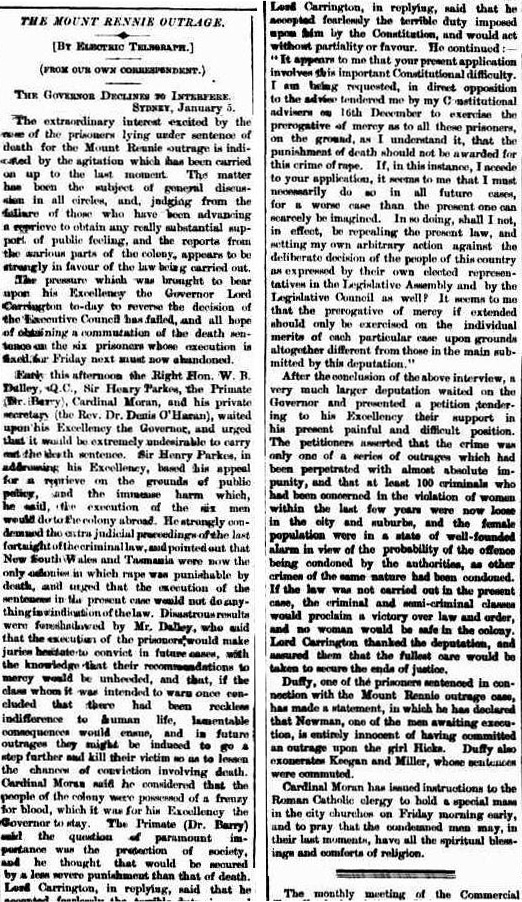

[media]In 1887 the trial, conviction and eventual hanging of four young men for the gang rape of Mary Jane Hicks at Moore Park in September 1886 produced extraordinary conflict around issues of urban life, masculinity, and the values of the growing Australian nation. The Mount Rennie rape, as it became known, became a story that could not be detached from its historical context. It was an event that shamed a city, and many, including Judge Windeyer, a fervent advocate of women's rights, demanded severe punishment as a deterrent. Some criticised the harshness of the penalty (hanging was a rare outcome for the crime of rape), while others criticised the larrikin behaviour that could produce such a crime. [22]

One hundred years later, the gang rape and murder of Sydney nurse Anita Cobby at Blacktown in February 1986 provoked equivalent outrage. The particularly brutal nature of the crime inspired calls for the reintroduction of the death penalty. Longer term impacts were evident in accelerating public support for tougher penalties for serious crime and enhanced resources and powers for police. The dignified response of Cobby's father, Garry Lynch, to the terrible circumstances of his daughter's murder contributed to the authority of the growing movement for victim's rights. Nearly 20 years later, Anita Cobby's story, with its many contradictory reverberations, was commemorated in an exhibition at Penrith's Regional Gallery. [23]

Laughing at the law

No [media]treatment of the theme of law and order in a city's history can ignore the role of those who contest the politics of the subject. As we have seen here, law and order campaigns thrive not just on the evidence of infractions, agitations, disorder and serious crime, but on the political possibilities that these events allow. The opponent or critic of law and order politics is another kind of player in this urban drama. Historically such critics have waged their own campaigns, using the weapons of the street demonstration, the organised political movement, the intellectual critique [24] or the endless possibilities of the media and cultural life. One result has been a rich cultural history of opposition, expressed in satire as much as in direct political challenge.

[media]A group of comedians from a weekly TV satirical show, The Chaser , breached the security cordon constructed in defence of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting of world leaders in Sydney in October 2007, gaining international attention. Their actions simultaneously advertised the vulnerability of a particular style of security policing and the liveliness of a culture that refused to take such an approach too seriously. This seemed to endorse the possibility that Sydney was still more 'Tinsel Town' than 'St Petersburg'. [25]

References

J Allen, Sex & secrets: crimes involving Australian women since 1880, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1990

K Amos, The New Guard movement 1931–1935, Melbourne University Press, Carlton Vic, 1976

K Amos, The Fenians in Australia 1865–1880, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1988

A Atkinson, The Europeans in Australia: a History, Volume One: The Beginnings, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne Vic, 1997

A Atkinson and M Aveling, Australians 1838, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon, Sydney, 1987

C Cunneen, Conflict, politics and crime: Aboriginal communities and the police, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest NSW, 2001

C Cunneen, 'Riot, resistance and moral panic: demonising the colonial other, in S Poynting and G Morgan (eds), Outrageous!: Moral Panics in Australia, ACYS Publishing, Hobart Tas, 2007, pp 20–29

A Curthoys, 'Liberalism and exclusionism: a prehistory of the White Australia policy', in L Jayasuriya, D Walker and J Gothard (eds), Legacies of White Australia: Race, Culture and Nation, University of Western Australia Press, Crawley WA, 2003, pp 8–32, 216–220, 251–256

J Davidson, The Sydney–Melbourne book, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1986

S Egger and M Findlay, 'The politics of police discretion', in M Findlay and R Hogg (eds), Understanding crime and criminal justice, Law Book Co, Sydney, 1988

M Finnane, 'The politics of police powers', in M Finnane (ed), Policing in Australia: Historical Perspectives, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1987

M Finnane, When police unionise: the politics of law and order in Australia, Institute of Criminology, University of Sydney, Sydney, 2002

S Garton, '"Feed him to the sharks": the Graeme Thorne kidnapping', in David Walker, Stephen Garton and Julia Horne (eds), 'Crimes and Trials', special issue of Australian Cultural History, vol 12, 1993, pp 29–42

K Gleeson, 'White natives and gang rape at the time of centenary' in S Poynting and G Morgan (eds), Outrageous!: Moral Panics in Australia, ACYS Publishing, Hobart, 2007, pp 171–180

PN Grabosky, Sydney in ferment: crime, dissent and official reaction 1788–1973, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1977

R Hogg and D Brown, Rethinking law and order, Pluto Press, Annandale NSW, 1998

KS Inglis, The Australian Colonists: an exploration of social history, 1788–1870, Melbourne University Press, Carlton Vic, 1974

JS Kerr, Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Australia's Places of Confinement, 1788–1988, SH Ervin Gallery, National Trust of Australia (New South Wales), Sydney, 1988

A Moore, Francis de Groot: Irish fascist, Australian legend, Federation Press, Leichhardt NSW, 2005

J Murray, Larrikins, 19th century outrage, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1973

S Poynting, '"Thugs" and "grubs" at Cronulla: from media beat-ups to beating up migrants', in S Poynting and G Morgan (eds), Outrageous!: Moral Panics in Australia, ACYS Publishing, Hobart, 2007, pp 158–170

N Sanders, 'TV family 1960: TV, gambling and the Graeme Thorne case', in David Walker, Stephen Garton and Julia Horne (eds), 'Crimes and Trials', special issue of Australian Cultural History, vol 12, 1993, pp 43–51

T Serisier, '"Remembering Anita": rape and the politics of commemoration' in Australian Feminist Law Journal, 23 Dec 2005, pp 121–145

AGL Shaw, Convicts and the colonies: a study of penal transportation from Great Britain and Ireland to Australia and other parts of the British Empire, Melbourne University Press, Carlton Vic, 1977

M Sturma, Vice in a vicious society: crime and convicts in mid-nineteenth-century New South Wales, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Qld, 1983

I Turner, Sydney's burning, Alpha Books, Sydney, 1969

D Walker, 'Youth on trial: the Mt Rennie case', Labour History, vol 50, 1986, pp 28–41

D Weatherburn, Law and order in Australia: rhetoric and reality, Federation Press, Annandale NSW, 2004

R White, 'Taking it to the streets: the larrikins and the Lebanese', in S Poynting and G Morgan (eds), Outrageous!: Moral Panics in Australia, ACYS Publishing, Hobart, 2007, pp 40–52

PR Wilson and D Chappell, 'The Law and Order Issue and Police-Public Relations', ANZ Journal of Criminology, vol 42, 1971, pp 112–116

G Wotherspoon, 'The greatest menace facing Australia: homosexuality and the state in NSW during the Cold War', Labour History, vol 56, 1989, pp 15–28

B York, Empire and race: the Maltese in Australia 1881–1949, New South Wales University Press, Kensington NSW, 1990

Notes

[1] JS Kerr, Out of Sight, Out of Mind Australia's Places of Confinement, 1788–1988, SH Ervin Gallery, National Trust of Australia (New South Wales), Sydney, 1988

[2] KS Inglis, The Australian Colonists: an exploration of social history, 1788–1870, Melbourne University Press, Carlton Vic, 1974

[3] A Atkinson, The Europeans in Australia: A History, Volume One: The Beginnings, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne Vic, 1997

[4] Centre for Comparative Law History and Governance of Macquarie University and State Records New South Wales, Proclamations &c Proclamation by His Excellency Lachlan Macquarie Esquire Captain General: 4 May 1816, accessed 5 December 2008, http://www.law.mq.edu.au/scnsw/Correspondence/6.htm

[5] C Cunneen, Conflict, politics and crime: Aboriginal communities and the police, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest NSW, 2001; C Cunneen, 'Riot, resistance and moral panic: demonising the colonial other', in S Poynting and G Morgan (eds), Outrageous!: Moral Panics in Australia, ACYS Publishing, Hobart Tas, 2007, pp 20–29

[6] A Atkinson and M Aveling, Australians 1838, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon, Sydney, 1987, ch 9

[7] M Sturma, Vice in a vicious society: crime and convicts in mid-nineteenth-century New South Wales, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia Qld, 1983

[8] PN Grabosky, Sydney in ferment: crime, dissent and official reaction 1788–1973, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1977, pp 37

[9] K Amos, The New Guard movement 1931–1935, Melbourne University Press, Carlton Vic, 1976; A Moore, Francis de Groot: Irish fascist, Australian legend, Federation Press, Leichhardt, NSW, 2005; I Turner, Sydney's burning, Alpha Books, Sydney, 1969

[10] J Murray, Larrikins, 19th century outrage, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1973; R White, 'Taking it to the streets: the larrikins and the Lebanese', in S Poynting and G Morgan (eds), Outrageous!: Moral Panics in Australia, ACYS Publishing, Hobart, 2007, pp 40–52

[11] S Poynting, '"Thugs" and "grubs" at Cronulla: from media beat-ups to beating up migrants', in S Poynting and G Morgan (eds), Outrageous!: Moral Panics in Australia, ACYS Publishing, Hobart, 2007, pp 158–170

[12] M Sturma, Vice in a vicious society: crime and convicts in mid-nineteenth-century New South Wales, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia Qld, 1983

[13] M Finnane, 'The politics of police powers', in M Finnane (ed), Policing in Australia: Historical Perspectives, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1987; S Egger and M Findlay, 'The politics of police discretion', in M Findlay and R Hogg (eds), Understanding crime and criminal justice, Law Book Co, Sydney, 1988, pp xiii, 349

[14] K Amos, The Fenians in Australia 1865–1880, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1988

[15] AGL Shaw, Convicts and the colonies: a study of penal transportation from Great Britain and Ireland to Australia and other parts of the British Empire, Melbourne University Press, Carlton Vic, 1977

[16] A Curthoys, 'Liberalism and exclusionism: a prehistory of the White Australia policy', in L Jayasuriya, D Walker and J Gothard (eds), Legacies of White Australia: Race, Culture and Nation, University of Western Australia Press, Crawley WA, 2003, pp 8–32, 216–220, 251–256

[17] B York, Empire and race: the Maltese in Australia 1881–1949, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1990

[18] PR Wilson and D Chappell, 'The Law and Order Issue and Police-Public Relations', ANZ Journal of Criminology, vol 42, 1971, pp 112–116

[19] G Wotherspoon, 'The greatest menace facing Australia: homosexuality and the state in NSW during the Cold War', Labour History, vol 56, 1989, pp 15–28

[20] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 Jan 1965, p 1; Daily Mirror, 17 January 1965; M Finnane, When police unionise: the politics of law and order in Australia, Institute of Criminology, University of Sydney, Sydney, 2002

[21] S Garton, '"Feed him to the sharks": the Graeme Thorne kidnapping', in David Walker, Stephen Garton and Julia Horne (eds), 'Crimes and Trials', special issue of Australian Cultural History, vol 12, 1993, pp 29–42; N Sanders, 'TV family 1960: TV, gambling and the Graeme Thorne case', in David Walker, Stephen Garton and Julia Horne (eds), 'Crimes and Trials', special issue of Australian Cultural History, vol 12, 1993, pp 43–51

[22] J Allen, Sex & secrets: crimes involving Australian women since 1880, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1990; K Gleeson, 'White natives and gang rape at the time of centenary', in S Poynting and G Morgan (eds), Outrageous!: Moral Panics in Australia, ACYS Publishing, Hobart, 2007, pp 171–180; D Walker, 'Youth on trial: the Mt Rennie case' in Labour History, vol 50, 1986, pp 28–41

[23] Penrith Regional Gallery, 'Anita and beyond', accessed 3 December 2008, http://www.penrithregionalgallery.org/archives/Archives2003/anita.htm; T Serisier, '"Remembering Anita": rape and the politics of commemoration', Australian Feminist Law Journal, 23 Dec 2005, pp 121–145

[24] R Hogg and D Brown, Rethinking law and order, Pluto Press, Annandale NSW, 1998; D Weatherburn, Law and order in Australia: rhetoric and reality, Federation Press, Annandale NSW, 2004

[25] J Davidson, The Sydney–Melbourne book, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1986

.