The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Prince Alfred Park, Parramatta

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Prince Alfred Park

[media]This princely park began its life as a pauper. Today, Prince Alfred Park is a public recreational space bounded by Church and Market streets, Victoria Road and Marist Place. In the colonial era, though, it was known as 'the Gaol Green' and 'the Hanging Green' – the site of Parramatta's first two gaols, court-ordered punishments and executions. Between 1802 and 1821, the upper floor of the second gaol also housed the 'factory above the gaol,' the first of two female factories at Parramatta. Both the gaol and the Female Factory were relocated to separate locations in North Parramatta after the building deteriorated and proved inadequate for the young colony's ever-increasing convict population.

With the green vacated, and its history of crime and punishment a rapidly fading memory (in part due to its 1860s rebranding as 'Alfred Square,' the namesake of a royal visitor) the space entered a new phase as a public park. Yet, as reports of heated debates in Parramatta Borough Council [1] and the evidence of civic-minded townspeople pushing for its beautification and maintenance attest, it was the incorporation of Parramatta as a municipality that was most instrumental in bringing about the site's metamorphosis from a grim place where lowly convicts were incarcerated and executed to a space worthy of a royal title.

The Gaol Green or the Hanging Green, 1796–1842

[media]Originally a Burramatta 'women's site', by the 1790s the area that is now the park as well as the space currently occupied by the Riverside Theatres contained government farm buildings and women's convict huts. By the end of the decade these structures were replaced by Parramatta’s first gaol. [2] After inmates set the log prison alight in December 1799, a second two-storey stone prison was constructed on the same spot in August 1802. Its upper level served as a wool and linen factory for female convicts to work in by day and as a refuge for the women by night. In 1821, the factory section of the gaol complex was relocated to the purpose-built Female Factory at the end of Greenup Drive, off Fleet Street in North Parramatta.

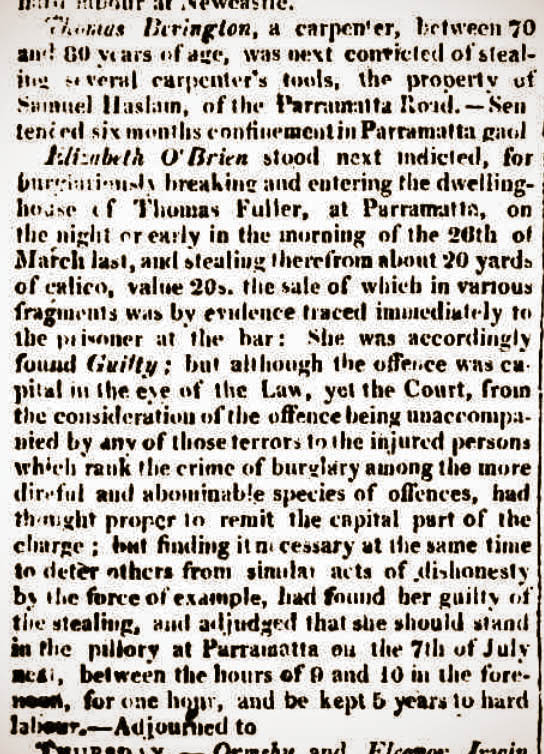

[media]More than one 'Old Parramattan' wistfully reminisced in the late nineteenth century about the 'good old days' when it was a common sight to see eight or nine 'refractory criminals' – male and female – doing time in the stocks set up outside the gaol walls for all and sundry to behold. [3] According to one such old-timer, Mr Gilbert Smith, the stocks' inhabitants had usually been found guilty of drunkenness and chose two hours in the stocks over a fine of five shillings. [media]Since no one was permitted 'to pelt or otherwise molest the culprits' whilst in this vulnerable posture, it might have been preferable to grin, bear it, and hold on to one's money. [4]

[media]However, Mr Smith's fond recollections of the good old days, in which regular punishments were passed off as a harmless form of public amusement, are a nostalgic and sanitised version of the Gaol Green, for public executions in the form of hangings were carried out here, too. The most famous of these executions occurred in 1804 when three men identified as ringleaders in the Castle Hill rebellion 'The Battle of Vinegar Hill' were hanged here. One of those three, Samuel Humes, was also gibbeted; a gruesome practice in which an executed person's body was hung in chains from gallows to deter other members of the public from engaging in similar unlawful activities. Although the area was deemed a 'village green' as early as 1837, the site's criminal past was not completely behind it until 1842 when a new, larger prison facility opened on the corner of Dunlop and New streets in North Parramatta.

The village green, 1837–1868

With work on the new gaol underway, on 27 November 1837 Governor Bourke authorised the use of the Gaol Green as a public reserve covering over three acres. While a fence demarcating and enclosing the new space was erected, and some alterations were made to the land with the aim of making it more pedestrian friendly, by 1853 townspeople complained that their common area was being used as a rubbish dump. [5] However, the difficulty of maintaining and developing communal spaces was soon to be improved by the introduction of the new Municipalities Act 1858 , which localised government [6] and gave the subsequent council the authority to allocate funds to improve community services and spaces. On 27 November 1861, the Municipality of Parramatta was proclaimed and by January 1862 Parramatta had its first mayor in the form of a (pardoned) pick-pocketing convict turned publican, John Williams, whose life trajectory was in its own right akin to a pauper-to-prince transformation. [7]

Alfred Square, 1867–1900s

After a real-life prince, Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, became the first British royal to tour the colony in 1867 and 1868, the park's transformation began in earnest. He visited Parramatta, arriving by river, and was greeted at the wharf by heavy rain and all the townspeople who were apparently unperturbed by the inclement weather. [8] To honour him, the village green was named 'Alfred Square' and soon after a special 'Tree-planting Committee' was formed within the Parramatta Borough Council. [9]

By 1871, the council also opened tenders for Alfred Square 'for the purpose of depasturing stock' [10] and 'carting'. [11] They even considered the area for the location of the greatly desired and much needed Parramatta Town Hall before the old market site in Centennial Square, also known as Parramatta Square, [12] was deemed more suitable. [13] [media]To mark Parramatta's centenary in 1888, the Anderson Fountain was moved from its original location near the Town Hall to Alfred Square to make way for the more ornate Centennial Fountain. [14] Despite its treatment as Centenary Square's inferior, Alfred Square was nonetheless a vibrant community space that hosted a wide range of local events. In the 1880s, for example, events included open-air moonlight and afternoon concerts, [15] a 'great...go-as-you-please' 48-hour tournament in a 'monster marquee' capable of holding 3,000 people and 'brilliantly illuminated each evening,' [16] as well as a 'Words of Grace Tent' where locals could attend evangelistic services. [17] In late 1889, council discussed the construction of a bandstand in Alfred Square [18] for the local band concerts [19] that had become a regular occurrence. In December 1890 the bandstand, built by James S Leggott – builder, carpenter and joiner of Alfred Street, Granville – was 'commencing to assume a shape;' [20] specifically the [media]shape of a late Victorian rotunda featuring 'decorative cast iron posts, brackets and valance capped with a copper roof.' [21]

The beautification of the reserve, however, was not without its challenges. Freak storms [22] led to the costly damage of railings and 'trespassing cattle' [23] tore and bruised the park's only oak tree. Young 'Sunday Larrikins' and 'hoodlums' were also known to be 'violently opening the large gates...defacing the palisade fence,' [24] and throwing rocks at the trees, causing them – as well as innocent bystanders – serious injury. [25] The fences were in a constant state of dilapidation but limited funds meant temporary repairs were favoured over replacements [26] and when new fences were authorised, the contractor could not be compelled to finish the work in a timely manner. [27]

Then there were some notable design flaws: 'Anyone passing through hurriedly the wicket gates in Alfred-square would be brought to a sudden halt at either gate by an obstruction in the shape of a lamp post,' wrote the Sydney Morning Herald's Parramatta correspondent in 1880. Driving home his point that this was a great evil that needed to be remedied, the correspondent made a visually rich reference to the notorious rotundity of the comedic Shakespearean character Falstaff: 'A lady, of the Falstaff appearance, was baulked the other day in getting through, while five other pedestrians were waiting their turn.' [28]

To the chagrin of many locals and aldermen, footpaths in the square were not asphalted until the close of 1889. Contemporary media reports indicate this improvement was finally carried out to prevent Alderman Taylor from using the 'disgraceful' condition of the square to influence municipal elections in his favour, as much as it was to prevent injury to the public. [29] Nevertheless, reports of the 'perfect eyesore' that was the square, which was otherwise beautiful 'when everything in connection with the flower-beds, and the fences, and so on, was in proper order,' continued well into the 1900s. [30] Indeed, the square was allegedly so neglected that upon the death of Prince Alfred on 30 July 1900, one reporter asserted, 'There is no need for Alfred Square to go into mourning for the Duke as it couldn't look more woe-begone that it has done these months past, if it tried ever so.' [31]

Prince Alfred Park

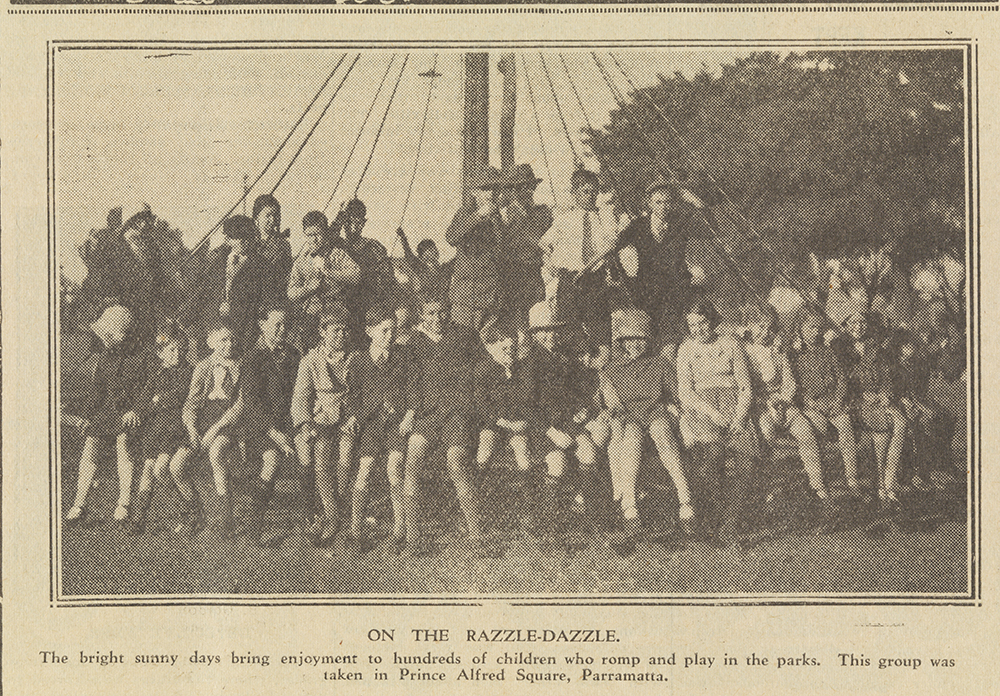

[media]The first half of the twentieth century saw a number of notable additions to this civic space. Landscaping and the addition of architectural features endowed the park with a greater sense of grandeur; a change that is perhaps reflected in the gradual transition of the toponym 'Alfred Square' to a fully-fledged princely park. Both names were used interchangeably but 'Prince Alfred Park' finally eclipsed the humbler appellation of Alfred Square.

In the Federation era, particularly, the park began to adopt its current visage with the inclusion of an avenue of Phoenix canariensis palms, which created the south-east/north-west diagonal pathway recognisable today. A second, south-west/north-east diagonal avenue was added in the mid-twentieth century with the planting of brush box and jacaranda, while Washingtonia robusta palms, jelly palms and firewheel trees were also planted elsewhere in the park. [32]

The Parramatta War Memorial was constructed in 1922 to commemorate World War I and, eventually, other subsequent conflicts. Another interesting but less imposing feature of the park from the interwar era is the State Heritage listed 'Bills Horse Trough' on the Victoria Road footpath, one of 500 troughs built around 1930 throughout New South Wales and Victoria. [33]

The last major addition to the park was the Gollan Memorial Clock Tower built in 1954 on the corner of Church Street and Victoria Road. [34] This sandstone turret clock was a source of constant complaint due to conflicting times being shown on its multiple faces until 2003 when technology was installed enabling it to be controlled by a master clock. [35]

For all its superficial changes, Prince Alfred Park has retained its fundamental function as a space where locals can enjoy 'brilliant illuminated' festive events such as Parramasala and Winterlight, during which the night air is 'made sweet with melodious strains' [36] just as it was over one hundred years ago. [37]

References

Arfanis, Peter. 'The Anderson Fountain, Parramatta – A Surgeon's Gift.' Parramatta Heritage Centre, 14 June 2014. http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2014/06/04/the-anderson-fountain-a-surgeons-gift/. Viewed 16 July 2014.

'Prince Alfred Park, Victoria Rd, Parramatta, NSW, Australia,' Australian Heritage Database, Australian Government Department of the Environment. http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/ahdb/search.pl?mode=place_detail;place_id=101962. Viewed 16 July 2014.

Kass, Terry, Carol Liston and John McClymont. Eds. Parramatta: A Past Revealed. Parramatta. Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996.

'Parramatta Female Factory Precinct', Parramatta Factory Precinct Association, http://www.parragirls.org.au/history.php. Viewed 13 July 2014.

Shand, Matt. 'Winterlight is back with a new location.' Parramatta Advertiser, 21 June, 2014. http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/competitions/winterlight-is-back-with-a-new-location/story-fngy6zkg-1226961564809?nk=0c00ca967ab133215ee401fdc3ec1f0e. Viewed 16 July 2014.

State Heritage Register, Heritage Council of NSW supported by the Heritage Division of the Office of Environment and Heritage. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/Heritage/searchesdirectories.htm. Viewed 16 July 2014.

Notes

[1] 'Parramatta Borough Council,' Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 16 November 1889, 3

[2] 'Parramatta Archaeological Management Unit 3110 / Prince Alfred Park, First and Second Parramatta Gaols,' State Heritage Register, Heritage Council of NSW supported by the Heritage Division of the Office of Environment and Heritage, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2243110, viewed 12 July 2014; Regarding Aboriginal women's site and convict women's huts, see 'Parramatta Female Factory Precinct,' Parramatta Factory Precinct Association, http://www.parragirls.org.au/history.php, viewed 13 July 2014

[3] Samuel Bennett, Evening News, Thursday 3 August 1871, 4; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 17 December 1904, 12; Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 2 January 1884, 8

[4] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 17 December 1904, 12

[5] 'Parramatta Archaeological Management Unit 3110 / Prince Alfred Park, First and Second Parramatta Gaols,' State Heritage Register, Heritage Council of NSW supported by the Heritage Division of the Office of Environment and Heritage, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx, viewed 12 July 2014

[6] Terry Kass, Carol Liston and John McClymont, Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 180

[7] 'From UK Floating Prisons to the First Mayor of Parramatta', Ancestry.com.au, http://www.ancestryeurope.lu/press/press-releases/australia/2010/09/from-uk-floating-prisons-to-the-first-mayor-of-parramatta/, viewed 15 July2014

[8] 'His Visit to Parramatta,' Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 8 August 1900, 2

[9] Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 13 October 1870, 5

[10] Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 19 January 1871, 2

[11] Evening News, Friday 24 January 1873, 4

[12] Renamed 'Centenary Square' in 2014 when the space was redeveloped.

[13] Terry Kass, Carol Liston and John McClymont, Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 182

[14] Evening News, Monday 6 August 1888, 3; Peter Arfanis, 'The Anderson Fountain, Parramatta – A Surgeon's Gift,' Parramatta Heritage Centre, http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2014/06/04/the-anderson-fountain-a-surgeons-gift/, viewed 16 July2014

[15] Sydney Morning Herald, Friday 5 November 1886, 7; Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 13 November 1886, 11; Australian Town and Country Journal, Saturday 6 April 1889, 16

[16] Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 4 August 1880, 2

[17] Evening News, Tuesday 7 September 1880, 4

[18] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 30 November 1889, 8

[19] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 5 October 1907, 1

[20] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 15 November 1890, 2; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 6 December 1890, 4

[21] Rotunda description sourced from the Australian Heritage Database, Australian Government Department of the Environment, http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/ahdb/search.pl?mode=place_detail;place_id=101962, viewed 16 July2014

[22] The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, Saturday 6 January 1872, 6; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 29 April 1903, 2

[23] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 21 March 1900, 2

[24] Evening News, Thursday 21 February 1878, 2; Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 28 March 1877, 7; Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 10 May 1877, 6; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 6 January 1904, 2; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 13 January 1904, 2

[25] Evening News, Wednesday 24 October 1888, 4; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday, 8, August 1900, 2; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 12 March 1902, 2; 'Destruction of Trees,' Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 27 November 1918, 2; 'Vandalism and Waste,' Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 19 April 1919, 6

[26] Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 23 December 1875, 3; Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 3 February 1876, 6; Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 4 March 1876, 5

[27] Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 7 December 1876, 6

[28] Evening News, Monday 8 March 1880, 3. Falstaff is a character in three of William Shakespeare's plays including Henry IV, Part I, Henry IV, Part II and The Merry Wives of Windsor. He is known for being fat and leading other characters into trouble.

[29] 'Parramatta Borough Council,' Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 16 November 1889, 3; 'Completion of the asphalting,' Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 30 November 1889, 8

[30] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 21 March 1900, 2; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 8 September 1900, 1; Evening News, Monday 26 March 1900, 3; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 14 July 1900, 1; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 8 September 1900, 1; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 24 November 1900, 12; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 27 April 1901, p.11; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 1 February 1902, 7; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 10 December 1904, 1

[31] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 8 August 1900, 2

[32] Australian Heritage Database, Australian Government Department of the Environment, http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/ahdb/search.pl?mode=place_detail;place_id=101962, viewed 16 July 2014

[33] 'Horse Trough,' 'Bills Horse Trough Adjacent to Prince Alfred Park,' State Heritage Register, Heritage Council of NSW supported by the Heritage Division of the Office of Environment and Heritage, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2240585, viewed 16 July 2014

[34] 'Gollan Clock,' Cumberland Argus, Wednesday 22 July 1953, 1. Note that this article says the Anderson Fountain was at the time located on the proposed spot of the Gollan Clock and that the fountain would be moved to another part of Alfred Square, where it is currently situated: the corner of Marist Place and Victoria Road.

[35] Natasha Wallace, 'Accurate and economical after 49 years – it's about time,' Sydney Morning Herald, 23 June 2003, http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2003/06/22/1056220478921.html, viewed 13 July 2014

[36] Australian Town and Country Journal, Saturday 6 April 1889, 16

[37] Elias Jahshan, Parramasala Festival to feature opening parade through Parramatta CBD for the first time,' Parramatta Advertiser, 5 September, 2013, http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/parramatta/parramasala-festival-to-feature-opening-parade-through-parramatta-cbd-for-the-first-time/story-fngr8huy-1226711336814, viewed 16 July 2014; Matt Shand, 'Winterlight is back with a new location,' Parramatta Advertiser, 21 June 2014, http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/competitions/winterlight-is-back-with-a-new-location/story-fngy6zkg-1226961564809?nk=0c00ca967ab133215ee401fdc3ec1f0e, viewed 16 July 2014

.