The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The colonial observations of Surgeon John White

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The observations of Surgeon John White

[media]Surgeon John White was head physician on the First Fleet expedition to Australia in 1788 and his journal provides valuable insights into the role and duties of an eighteenth century physician, health problems experienced by the First Fleet population and relationships with Aboriginal people . While there was some collaboration between Aboriginal people and the colonists, problems with food security caused numerous violent exchanges between Aboriginal people and colonists in the first two years of contact. White, however, developed strong relationships with Aboriginal people, especially with his ward Nanbaree .

The early career of Surgeon John White

The date and place of John White's birth has eluded historians, but it is believed he was born in 1756 in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. [1] He enlisted in the Royal Navy as a surgeon's mate on 26 June 1778 and three years later graduated with a diploma in the Company of Surgeons. White served under the command of Sir Andrew Snape Hammond on the British warship HMS Irresistible in June 1786, which served in the West Indies and India and he was responsible for a crew of around 600 men. [2] Hammond was impressed by White and recommended him as principal surgeon on the First Fleet expedition to Australia. White left London after receiving his commission on 5 March 1787 and travelled to Plymouth where the First Fleet was preparing for the voyage to Australia. [3]

Boosting the health of the First Fleet

White was responsible for the health of about 1500 people on the eleven transport ships of the First Fleet and assumed his duties with compassion and care. [4] After conducting an assessment of the prison population, many of whom were weakened by their confinement on the hulks, he explained to his superiors, Secretary of State Lord Sydney and Captain Arthur Phillip, the steps he had taken to bolster the stamina of the convicts .

Fresh provisions I dwelt most on, as being not only needful for the recovery of the sick, but otherwise essential, in order to prevent any of them commencing so long and tedious a voyage as they had before them with a scorbutic taint; a consequence that would most likely attend their living upon salt food; and which, added to their needful confinement and great numbers, would, in all probability, prove fatal to them, and thereby defeat the intention of Government. [5]

He provided them with fresh clothing and requested that convicts be given access to the upper decks of the transports to exercise for short periods each day '…in order that they might breathe a purer air, as nothing would conduce more to the preservation of their health.' [6] Respiratory diseases incubated in the damp holds so White sought the cooperation of officers of the First Fleet.

I mentioned to Captain Hunter, of the Sirius, that I thought whitewashing with quick lime the parts of the ships where the convicts were confined would be the means of correcting and preventing the unwholesome dampness which usually appeared on the beams and sides of the ships, and was occasioned by the breath of the people. Captain Hunter agreed with me on the propriety of the step: and with that obliging willingness which marks his character, made the necessary application to Commissioner Martin; who, on his part, as readily ordered the proper materials. The process was accordingly soon finished; and fully answered the purpose intended. [7]

White insisted on high standards of hygiene for the convict transports and ordered fresh provisions to increase the wellbeing of both convicts and marines.

First Fleet arrival at Botany Bay

[media]On 20 January 1788, following a nine-month sea voyage, the First Fleet sailed into the relatively calm waters of Botany Bay. White was relieved the voyage claimed few lives, and his preventative measures had worked.

To see all the ships safe in their destined port, without ever having, by any accident, been one hour separated, and all the people in as good health as could be expected or hoped for, after so long a voyage, was a sight truly pleasing, and at which every heart must rejoice. [8]

Captain Arthur Phillip soon determined Port Jackson had superior soils and fresh water stream (the Tank Stream). White recorded on 26 January that a site for the settlement had been selected.

That on which the town is to be built, is called Sydney Cove. It is one of the smallest in the harbor, but the most convenient, as ships of the greatest burden can with ease go into it, and heave out close to the shore. [9]

However for Aboriginal people observing the arrival of the First Fleet from the shore it may not have been so pleasing. White was sensitive to this possibility.

As we sailed into the bay, some of the natives were on the shore, looking with seeming attention at such large moving bodies coming amongst them. In the evening the boats were permitted to land on the north side, in order to get water and grass for the little stock we had remaining. An officer's guard was placed there to prevent the seamen from straggling, or having any improper intercourse with the natives. [10]

Failures of reciprocity

Historian Henry Reynolds [media]has pointed out that 'reciprocity and sharing were central to the social organisation and ethical standards of traditional society .' [11] To Aboriginal people the actions of colonists who entered land and took food, without offering anything in return, were unethical and unjust. At first the colonists found a way to negotiate.

While the people were employed on shore, the natives came several times among them, and behaved with a kind of cautious friendship. One evening while the seine was hauling, some of them were present, and expressed great surprise at what they saw, giving a shout expressive of astonishment and joy when they perceived the quantity that was caught. No sooner were the fish out of the water than they began to lay hold of them, as if they had a right to them, or that they were their own; upon which the officer of the boat, I think very properly, restrained them, giving, however, to each of them a part. They did not at first seem very well pleased with this mode of procedure, but on observing with what justice the fish was distributed they appeared content. [12]

According to Lieutenant David Collins this collaboration became regular .

The fishing-boats also frequently reported their having been visited by many of these people when hauling the seine, at which labour they often assisted with cheerfulness, and in return were generally rewarded with part of the fish taken. [13]

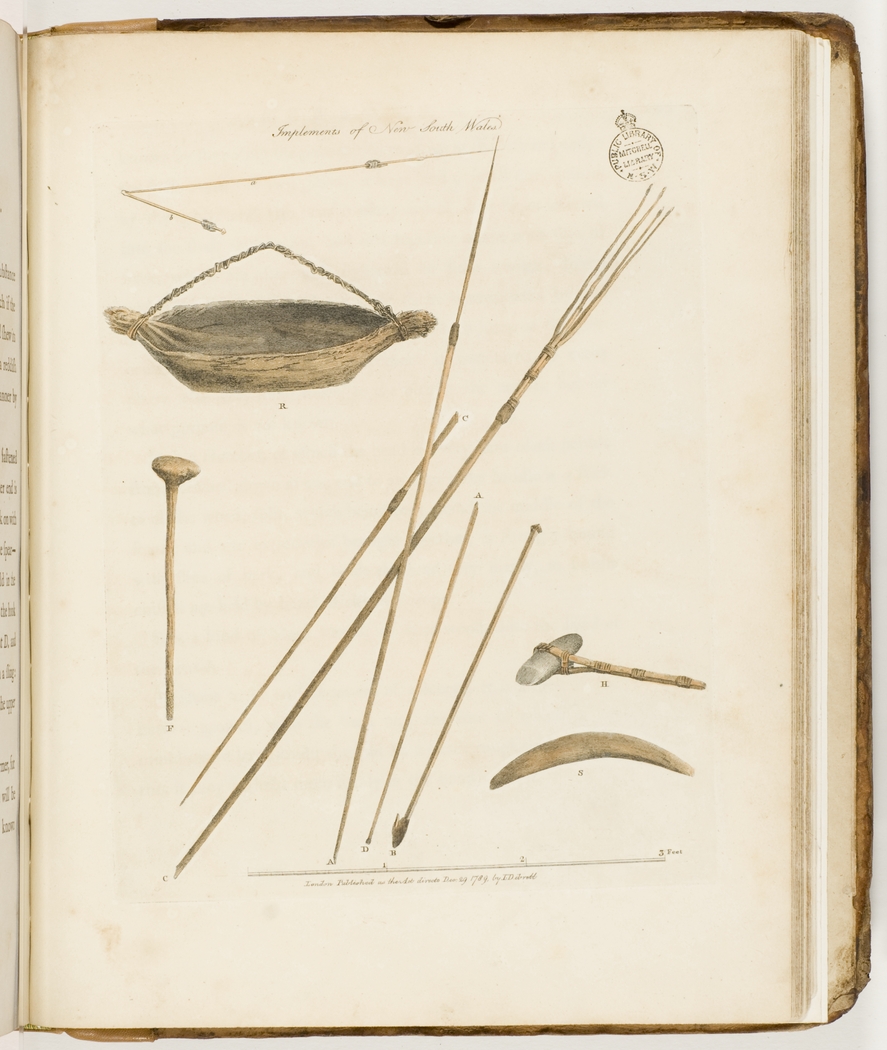

However the cooperation was short-lived. Although colonial officials warned fishing crews to treat Aboriginal people respectfully, Collins recorded '…these precautions were rendered fruitless by the ill conduct of a boats crew' which escalated into hostilities with the fishing party 'driven off with stones by the natives.' [14] Shortly afterward Aboriginal men conducted a hit-and-run raid on colonists who were preparing a garden. They took a shovel, spade and pickaxe before they were fired at and hit in the legs with small shot and dropped the axe. [15] A petty officer was stationed on fishing boats after an incident in which a group of Aboriginal people, armed with spears and other weapons, approached seine-fishers and 'with some show of method…took by force about half of what had been brought on shore.' [16]

Early Aboriginal resistance

White recorded that the lack of fresh food and vegetables at Sydney Cove soon caused a deterioration in health . Dysentery was rife.

This disorder has now risen to a most alarming height, without any possibility of checking it until some vegetables can be raised; which, from the season of the year, cannot take place for many months. [17]

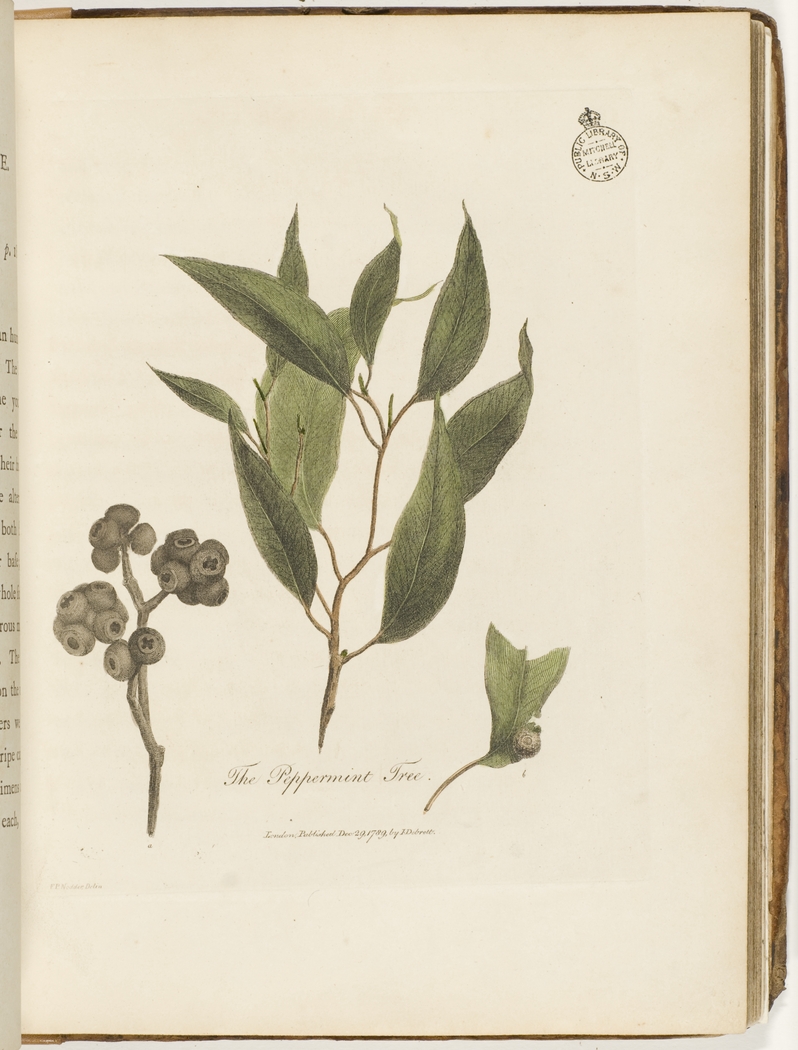

White realized that the situation was grave. He ordered convicts into the forests in search of edible plants to supplement the meagre ration diet. This became a dangerous task. On 21 May White conducted a difficult extraction of a spear, which required 'dilation of the wound', from convict William Ayres. Ayres had been 'gathering sweet tea … I had given permission to go a little way into the country, for the purpose of gathering a few herbs.' [18]

The following week two convicts who had been assigned duties away from the safety of the penal colony were mortally wounded and robbed of their clothing and tools.

Captain Campbell of the marines, who had been up the harbour to procure some rushes for thatch, brought to the hospital the bodies of William Okey and Samuel Davis, two rush-cutters, whom he had found murdered by the natives in a shocking manner. [19]

White conducted a post mortem on 30 May and set off the next day to investigate the homicides, the next day, accompanied by Governor Phillip, Lieutenants John Johnston and Robert Kellow, six soldiers and two armed . According to White 'the governor was resolved, on whomever he found any of the tools, or clothing, to show them his displeasure.' [20] After visiting the murder site and surrounding district the colonial retribution party was unable to identify the guilty parties.

Conflict over food

An article published in the 1940s recorded that the colony was in dire straights as winter approached.

The slow progress with building dwellings…the fact that even with incessant labour their gardens yielded them very little, the scarcity of fish and of wild greens, made the winter a very miserable one. [21]

Captain John Hunter observed the deterioration in health of both the colonial and Aboriginal populations.

In the month of July (1788), our scorbutic patients seemed to be rather worse; the want of a little fresh food for the sick was very much felt, and fish at this time were very scarce: such of the natives as we met seemed to be in a miserable and starving condition from that scarcity. [22]

Hunter recorded that Aboriginal people were able to source some bush foods.

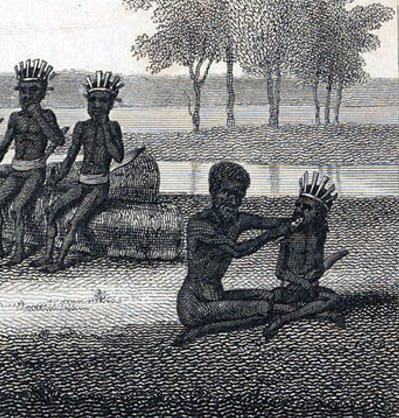

[media]They were frequently found gathering a kind of root in the woods, which they broiled on the fire, then beat it between two stones until it was quite soft; this they chew until they have extracted all the nutritive part, and afterwards throw it away . [23]

In these conditions, conflicts over fish became heightened. On 8 July 1788 White recorded Aboriginal people raided a fishing party from the Sirius and 'having beaten the crew, took from them by force a part of the fish which they had caught.' [24] Why the raiders only took a part of the catch was not clear. Perhaps it was a sense of sharing or maybe they only took what they needed.

White also recorded attacks on convicts who ventured inland.

A party of convicts, who had crossed the country to Botany Bay to gather a kind of plant resembling balm, which we found to be a good and pleasant vegetable, were met by a superior number of the natives, armed with spears and clubs, who chased them for two miles without being able to overtake them; but, if they had succeeded in the pursuit, it is probable that they would have put them to death, for wherever persons unarmed, or inferior in numbers, have fallen in with them, they have never failed to maltreat them. [25]

The desperate need of the colonists for food made them persistent, despite the dangers. White recorded another spearing on 29 July.

One of the convicts was met by some of the natives, who wounded him very severely in the breast and head with their spears. They would undoubtedly have destroyed him had he not plunged into the sea, near which he happened to be, and by that means saved himself. When he was brought to the hospital he was very faint from the loss of blood, which had flowed plentifully from his wounds. A piece of a broken spear had entered through the scalp and under his ear, so that the extraction gave him great pain. [26]

Guns were instrumental in preventing casualties amongst the colonists.

A convict who had been out gathering what they called sweet tea, about a mile from the camp, met a party of the natives, consisting of fourteen, by whom he was beaten, and also slightly wounded with the shell-stick used in throwing their spears; they then made him strip, and would have taken from him his clothes, and probably his life, had it not been for the report of two musquets; which they no sooner heard than they ran away. This party was returning from the wood with cork, which they had been cutting, either for their canoes or huts; and had with them no other instruments than those that were necessary for the business on which they were engaged, such as a stone hatchet, and the shell stick before mentioned. Had they been armed with any other weapons, the convict would probably have lost his life. [27]

It is evident that Aboriginal people were taking every opportunity to impede, diminish and counter the intrusion of colonists who were threatening their own food resources. According to Collins Aboriginal resistance included the use of dogs to attack the colonists' livestock.

The governor had the mortification to learn on his return from his western expedition, that five ewes and a lamb had been destroyed at the farm in the adjoining cove, supposed to have been killed by dogs belonging to the natives. [28]

Historian Richard Broome has called this 'a war for the land,' in which Aboriginal people adapted to the usurpation of their lands by conducting guerilla-style attacks on colonial livestock and food stores. [29] White recorded one such incident on 26 August 1788.

A few days since the natives landed near the hospital, where some goats belonging to the Supply were browsing, when they killed, with their spear, a kid, and carried it away. Within this fortnight, they have also killed a he-goat of the governor's. Whenever an opportunity offered, they have seldom failed to destroy whatever stock they could seize upon unobserved. They have been equally ready to attack the convicts on every occasion which presented itself; and some of them have become victims to these savages. [30]

What White was witnessing was to become a feature of frontier contact between colonists and Aboriginal people over the next century in many parts of Australia.

Colonial authorities sent armed marines to protect convicts gangs assigned to collect foods, but still the casualty list continued to rise, amid regular ambushes. [31] A letter from a female convict written on 4 November 1788 describes the fear of the colonists.

…the savages still continue to do us all the injury they can, which makes the soldiers' duty very hard, and much dissatisfaction among the officers. I know not how many of our people have been killed. [32]

Such was the volatility of relations that when colonists went missing it was immediately assumed that Aboriginal people had killed them, as White wrote on 28 October 1788.

A marine went to gather some greens and herbs, but has not returned; as he was unarmed, it is feared that he has been met and murdered by the natives.' [33]

Lorna Lippmann states 'a mounting nervous ensued', leading Phillip to change his policy and begin sending armed military parties to fire shots to compel Aboriginal people to stay away from the settlement. [34]

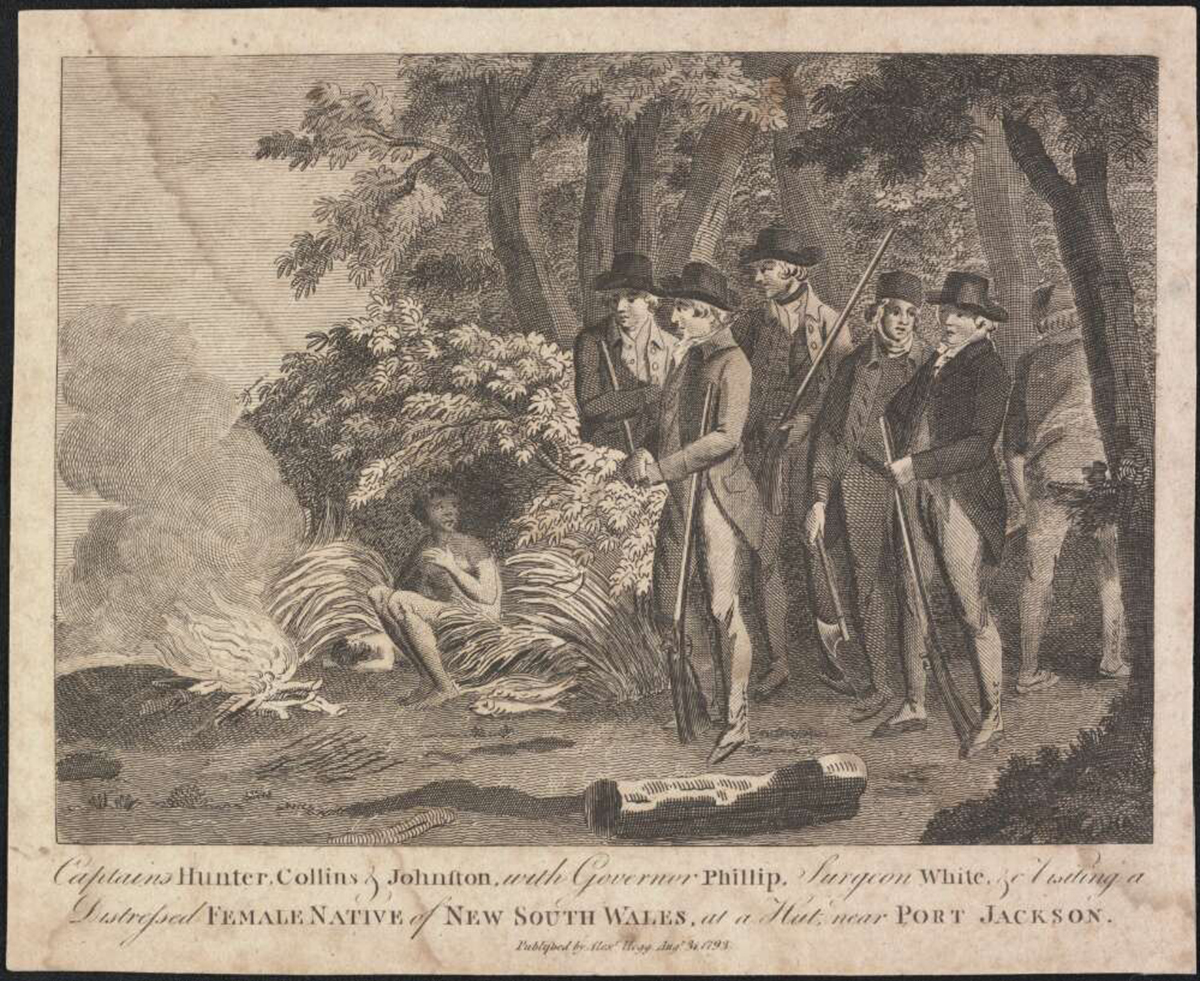

White and Nanbaree

Hostilities [media]continued over the next months but subsided following a devastating epidemic that struck Aboriginal communities in the Sydney district in April 1789, causing untold deaths . [35] David Collins records colonists fishing in the harbour rescued a family and took them to the hospital for treatment. The family included two children, a girl Abaroo and a boy Nanbaree, and was treated by White – Hunter noted the surgeon's treatment of Nanbaree revealed 'a humanity for which he is distinguished .' [36] White then adopted Nanbaree into his own family. [37]

In the following years White and Nanbaree developed a strong bond, signifying one of the earliest relationships between European and Aboriginal people. Nanbaree travelled with White on numerous excursions around the Sydney district acting as both intermediary and interpreter. Watkin Tench recounted one of these expeditions .

On the 7th instant, Captain Nepean, of the New South Wales Corps, and Mr. White, accompanied by little Nanbaree, and a party of men, went in a boat to Manly Cove, intending to land there, and walk on to Broken Bay. On drawing near the shore, a dead whale, in the most disgusting state of putrefaction, was seen lying on the beach, and at least two hundred Indians surrounding it, broiling the flesh on different fires, and feasting on it with the most extravagant marks of greediness and rapture. [38]

Yet again food was the centre of potential conflict, but according to White, Nanbaree was instrumental in defusing it.

As the boat continued to approach, they were observed to fall into confusion and to pick up their spears, on which our people lay upon their oars and Nanbaree, stepping forward, harangued them for some time, assuring them that we were friends. Mr. White now called for Baneelon who, on hearing his name, came forth, and entered into conversation. [39]

Shared hunger and health care

Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore, described the first five years of the colony as 'the starvation years'. [40] Collins noted of the colonists that 'Their universal plea was hunger.' [41] Convicts faced severe punishment for stealing food, as was the case for James Collington, who broke into the public bakehouse by getting down the chimney at night and took fifty pounds of flour . Collins was sympathetic.

He was induced by hunger to commit the crime for which he suffered. He appeared desirous of death, declaring that he knew he could not live without stealing.' [42]

[media]Convicts risked receiving up to three hundred lashes for pilfering, but Collins noted this did nothing to dissuade colonists from stealing .

It might have been supposed, that the severity of the punishments which had been ordered by the criminal court on offenders convicted of robbing gardens would have deterred others from committing that offence; but while there was a vegetable to steal, there were those who would steal it, wholly regardless as to the injustice done to the person they robbed, and of the consequences that might ensue to themselves. [43]

Unwary colonists found themselves robbed, especially after Phillip was forced to reduce rations.

It was naturally expected, that the miserable allowance which was issued would affect the health of the labouring convicts. A circumstance occurred on the 12th of this month, which seemed to favour this idea; an elderly man dropped down at the store, whither he had repaired with others to receive his day's subsistence. Fainting with hunger, and unable through age to hold up any longer, he was carried to the hospital, where he died the next morning. On being opened, his stomach was found quite empty. [44]

In this context, the colonists' hostile actions against Aboriginal people are more understandable. In December 1790 Tench records the tragic shooting of the Aboriginal man Bangai .

Two natives, about this time, were detected in robbing a potato garden. When seen, they ran away, and a sergeant and a party of soldiers were dispatched in pursuit of them. Unluckily it was dark when they overtook them, with some women at a fire; and the ardour of the soldiers transported them so far that, instead of capturing the offenders, they fired in among them. [45]

Imeerawanyee, an Aboriginal man, told White that Bangai may still be alive, and the surgeon rushed to his aid .

A hope now existed that his life might be saved; and Mr. White, taking Imeerawanyee, Nanbaree, and a woman with him, set out for the spot where he was reported to be. But on their reaching it, they were told by some people who were there that the man was dead...On examining the corpse, it was found to be warm. Through the shoulder had passed a musquet ball, which had divided the subclavian artery and caused death by loss of blood. [46]

Collins records other instances where White rendered assistance to Aboriginal people, such as the man Carradah, who had nerve damage to his left hand from a spear wound and the woman Boorong .

On her intimating to them that she found herself ill, they told her triumphantly what they had done. Not recovering, though bled in the arm by Mr. White, she underwent an extraordinary and superstitious operation.

White was also requested to attend burial ceremonies.

Enduring bond

[media]It is evident that despite hostilities a number of Aboriginal people felt a bond with White that endured throughout his stay in the penal colony, which ended in 1792 . According to Collins:

Nan-bar-ray's tooth Da-ring-ha wished me to give to Mr. White, the principal surgeon of the settlement, with whom the boy had lived from his being brought into it, in the year 1789, to Mr. White's departure; thus with gratitude remembering, after the lapse of some years, the attention which that gentleman had shown to her relative. [47]

When Nanbaree died many years later his obituary in the Sydney Gazette revealed that White had given his adopted son a European name made up of a combination of his former mentor Andrew Hammond and his own name.

On the 19th of last month died, at the residence of Mr. James Squire, Kissing Point, Andrew Snape Hammond Douglas White, a black native of the colony. He was about 37 years old; and was taken from the woods in a few months after the first establishment in 1788, by Dr White, after whom he was named. [48]

The career of John White provides valuable insights into the duties of an eighteenth century physician who was responsible for the well-being of a large penal population, in a strange environment, riven by food insecurity. He was the first European to medically treat Aboriginal people and was a man of compassion who wanted peace with Aboriginal people.

Further reading

Richard Broome. Aboriginal Australians Black responses to White Dominance 1788-2001. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2002.

Phillip Clarke. Australian Plant Collectors Botanists and Australian Aboriginal People in the Nineteenth Century. Dural: Rosenberg Publishing Pty Ltd, 2008.

David Collins. An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country. Edited by Brian H Fletcher. Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975.

Tim Flannery. 1788: Watkin Tench. Melbourne: Text Publishing Company, 1996.

John Hunter. An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792. Edited by John Bach. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1968.

Lorna Lippmann. Generations of Resistance Mabo and Justice. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire Pty Ltd, 1995.

Henry Reynolds. The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal Resistance to the European Invasion of Australia. Sydney: University of NSW Press, 2006.

Rex Rienits. 'White, John (1756–1832)'. Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography. Australian National University. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/white-john-2787/text3971.

John White. Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales. New York: Arno Press, 1971.

Notes

[1] E Charles Nelson, 'John White (c... 1756-l832), Surgeon-General of New South Wales: Biographical Notes on his Irish Origins, Irish Historical Studies, 25, no 100 (1987), 405-412, http://www...jstor...org/stable/30008564, viewed 9 March 2011

[2] Rex Rienits, 'White, John (1756–1832)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb...anu...edu...au/biography/white-john-2787/text3971, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed online 3 July 2015

[3] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 1

[4] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 1

[5] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 5-9

[6] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 5-9...

[7] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 9

[8] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 114

[9] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 121

[10] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 114

[11] Henry Reynolds, The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal Resistance to the European Invasion of Australia (Sydney: University of NSW Press, 2006), 74

[12] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 116

[13] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975), 12

[14] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975), 13

[15] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975)

[16] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975), 28-29

[17] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975), 158

[18] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 156

[19] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 160

[20] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 162

[21] L Davey, M MacPherson, FW Clements, 'The Hungry Years 1788-1792', Historical Studies, November 1947, 11

[22] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, ed John Bach (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1968), 55

[23] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, ed John Bach (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1968)

[24] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, ed John Bach (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1968), 183

[25] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 187...

[26] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 188...

[27] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 194-195

[28] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975), 21

[29] Richard Broome, Aboriginal Australians Black responses to White Dominance 1788-2001 (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2002), 45

[30] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 213...

[31] Phillip Clarke, Australian Plant Collectors Botanists and Australian Aboriginal People in the Nineteenth Century (Dural: Rosenberg Publishing Pty Ltd, 2008), 26

[32] Letters from a Female Convict, Historical Records of NSW, vol 2, 746-747, cited Alan Birch and David S MacMillan, The Sydney Scene 1788-1960 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1962), 34

[33] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 216

[34] Lorna Lippmann, Generations of Resistance Mabo and Justice (Melbourne: Longman Cheshire Pty Ltd, 1995), 4

[35] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, ed John Bach (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1968), 183

[36] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea 1787-1792, ed John Bach (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1968), 270

[37] Tim Flannery, 1788 Watkin Tench A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay and A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson (Melbourne: Text Publishing Company, 1996), 104-105

[38] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 114

[39] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 114

[40] Robert Hughes The Fatal Shore: A History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia 1787-1868 (London: Collins Harvill, 1987), 84

[41] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975), 175

[42] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975), 166

[43] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975), 90

[44] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975), 89

[45] Tim Flannery, 1788 Watkin Tench A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay and A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson (Melbourne: Text Publishing Company, 1996), 104-105, 177

[46] Tim Flannery, 1788 Watkin Tench A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay and A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson (Melbourne: Text Publishing Company, 1996), 104-105, 178

[47] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, ed Brian H Fletcher, vol 1 (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975), 483

[48] Sydney Gazette, 8 September 1821, 3

.