The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Advertising

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Advertising

Sydney [media]is Australia's advertising capital. Given the city's bustling, vibrant, and brash reputation, it seems obvious that the national advertising industry would reside in Sydney. However, the relationship between the city and the advertising industry stretches back to the earliest years of European settlement. Advertising helped propel commercial activity in Sydney, profiting handsomely from it in the process. While the city has left its mark on Australian advertising, the advertising industry has been no less active in shaping Sydney. In addition to illuminating the city's skyline and streetscape, advertising has also influenced the lives of all Sydneysiders – from suburban consumers to esteemed artists. Moreover, advertising has raised Sydney's international profile – as the must-see destination for tourists or as the backdrop for the latest blockbuster film.

Commercial foundations

Commercial [media]activity has been integral to Sydney's growth. During the penal colony's fledgling years, local industry was largely agricultural, with the timber and brick industries emerging to service the settlement's infrastructure. Importers were therefore vital in transporting and distributing goods and wares to local retailers, manufacturers and consumers. While the settlement's initial size meant that word of mouth was the most common form of advertising, ongoing expansion demanded a more efficient means of publicising goods or services.

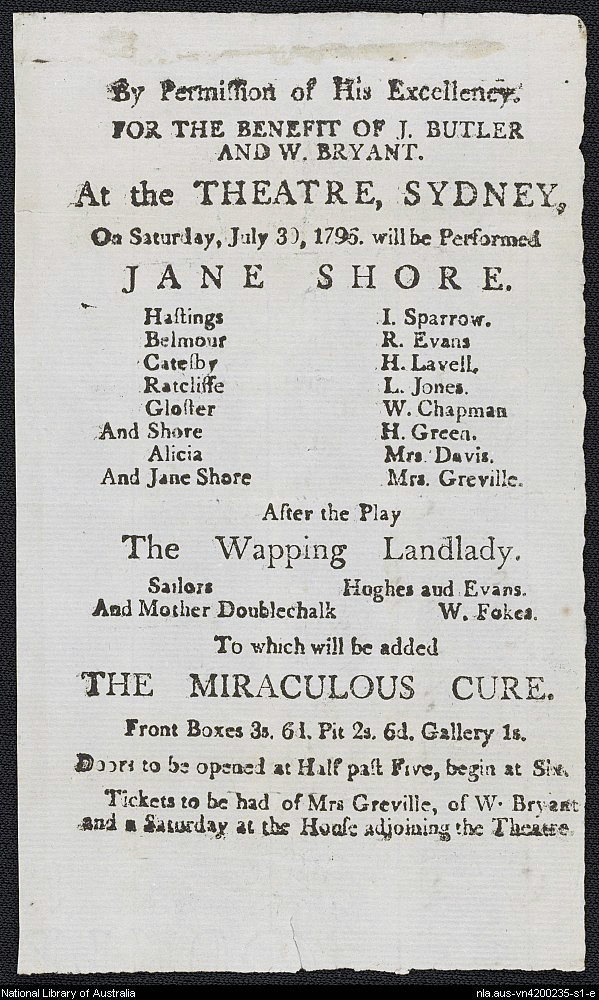

Among the items brought out to the new settlement by the First Fleet was a screw-press for reproducing government orders. Seven years would elapse before a printer was found to operate it and produce Sydney's first outdoor advertisements. [1] The press was soon put to commercial use, as the city's theatrical promoters printed handbills for their latest performances. With performances changing regularly, they also pioneered the use of street frontage to advertise current and upcoming shows. The growth of Sydney's retail sector stimulated further outdoor advertising. To delineate themselves from their competitors, retailers adorned their shop frontages with signs advertising their names, wares and prices. A growing number employed sign-writers in order to convey a more professional image. Over time, brand names would also assume a more prominent role in these shopfront displays.

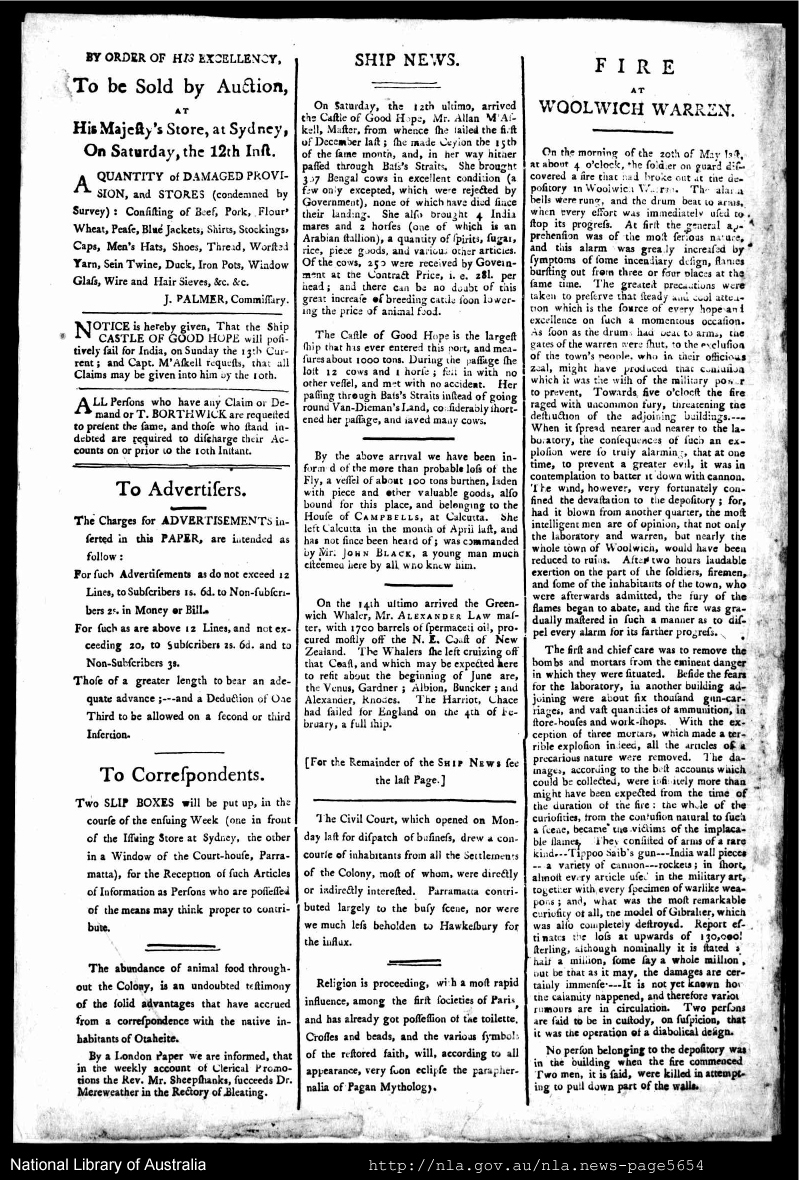

The colony's first newspaper offered another solution. [media]First published in 1803, the Sydney Gazette enabled commercial enterprises to speak directly to the entire colony through its advertising columns. Instantly lucrative, such columns established an interdependent relationship between local advertisers and the press. In subsequent issues, advertising material in the Sydney Gazette comprised almost two-thirds of each edition. [2] With land in abundant supply, auctioneers were first among local industries to dominate the advertising columns (laying, perhaps, the groundwork for the Harbour City's real estate fascination in the process). The Sydney Gazette's success led to the creation of further newspapers. While subscriptions to the early papers were their primary source of income, advertising revenue remained a welcome and expanding additional source. [3]

An advertising industry emerges

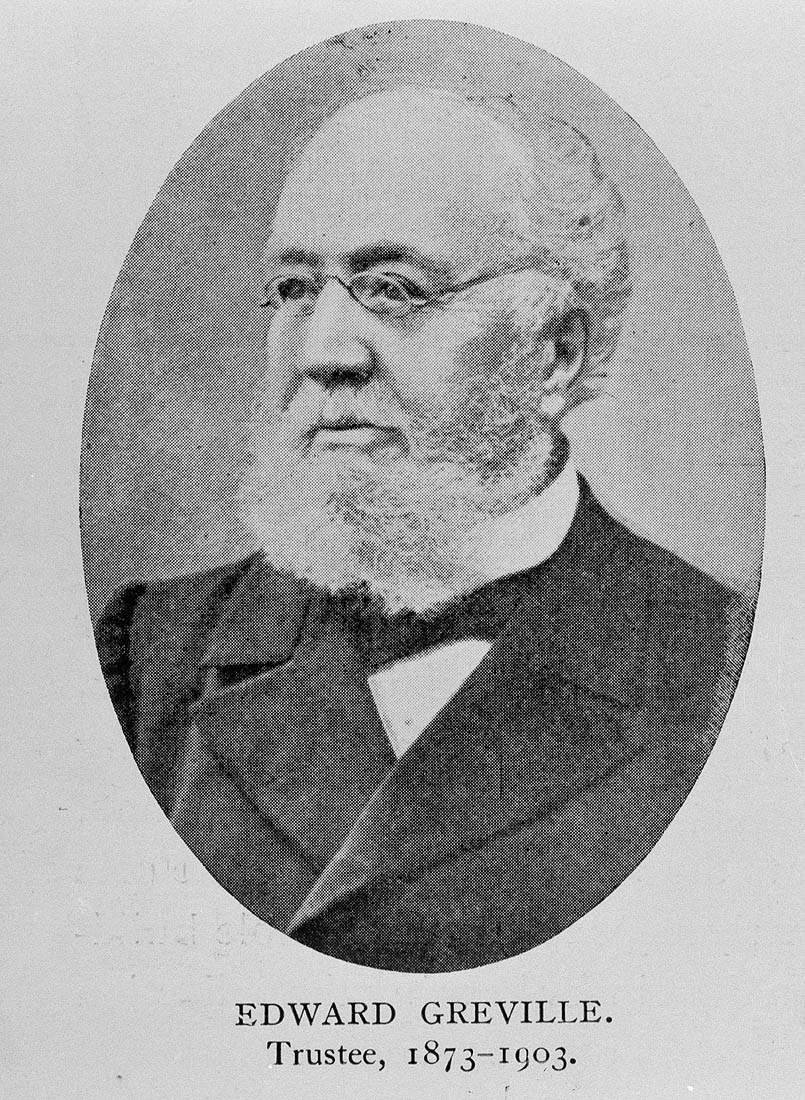

Advertising assumed a greater importance as commercial activity in Sydney increased. In the 1850s, the press was heavily dependent upon the activities of agents that made their living by selling news and reports to newspapers. [media]However, individuals such as Edward Greville identified and expanded their operations to include the sale of advertising space to advertisers. Others followed, and by the 1880s, FT Wimble & Company was also employing an artist. [4] However, it was the canvasser who became synonymous with advertising. Earning commissions from newspaper column inches sold to advertisers, canvassers sold space with little care for a publication's circulation. [5] It was then left to the advertiser to decide how this newly acquired space would be used. Most advertisers created their own newspaper advertisements, resulting in unimaginative and crude advertisements.

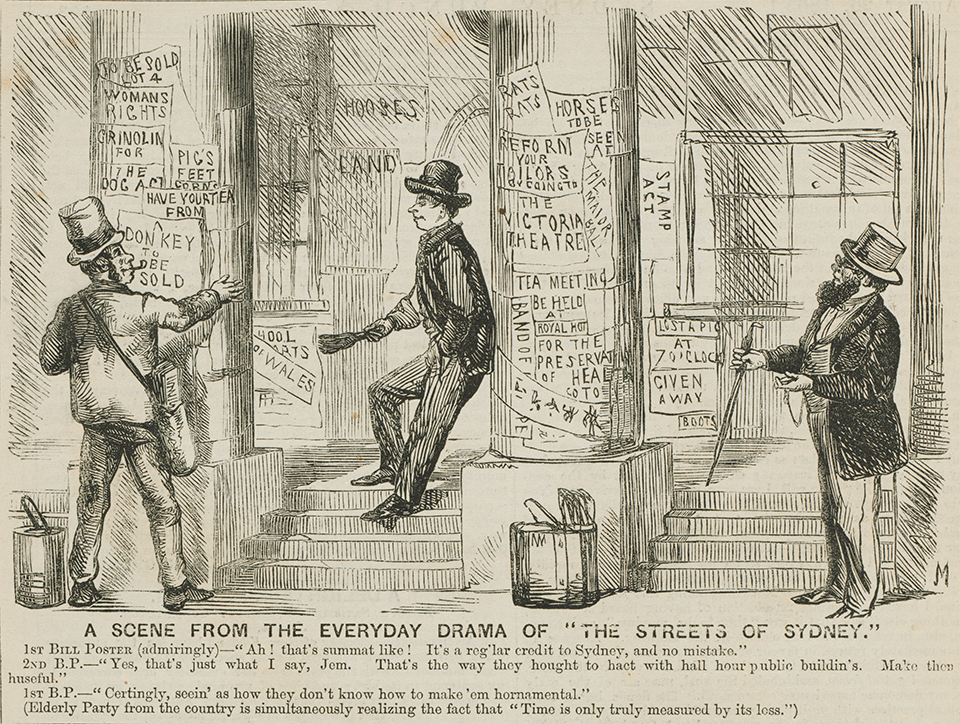

[media]Established in 1854, Isaac & Joseph Roff was Sydney's first producer of posters for commercial purposes. Outdoor advertising business quickly grew – as did competing firms. [media]The posters were applied to any available flat space, particularly around derelict buildings. By the late 1870s, Hollander & Govett was offering a more sophisticated service. In addition to printing posters, it also erected its own hoardings in prominent places and placed its clients' posters on them. These giant hoardings featured a cacophony of posters of varying sizes, colours, and appeals. [6] The growth of Sydney's public transport system provided yet another means for reaching the public with advertisements appearing on stations and inside each train, tram, ferry, or bus. Nostalgic reprints of posters from the 1930s can still be seen on the walls of Museum Station.

[media]Quack medicine proprietors and large department stores such as Anthony Hordern's and Mark Foy's were Sydney's first serious advertisers. Their in-house advertising departments produced appealing and effective advertisements. Although smaller firms were also recognising advertising's importance, few could afford their own advertising departments. Stepping into this breach were a handful of men offering to service these companies' advertising needs.

The first admen

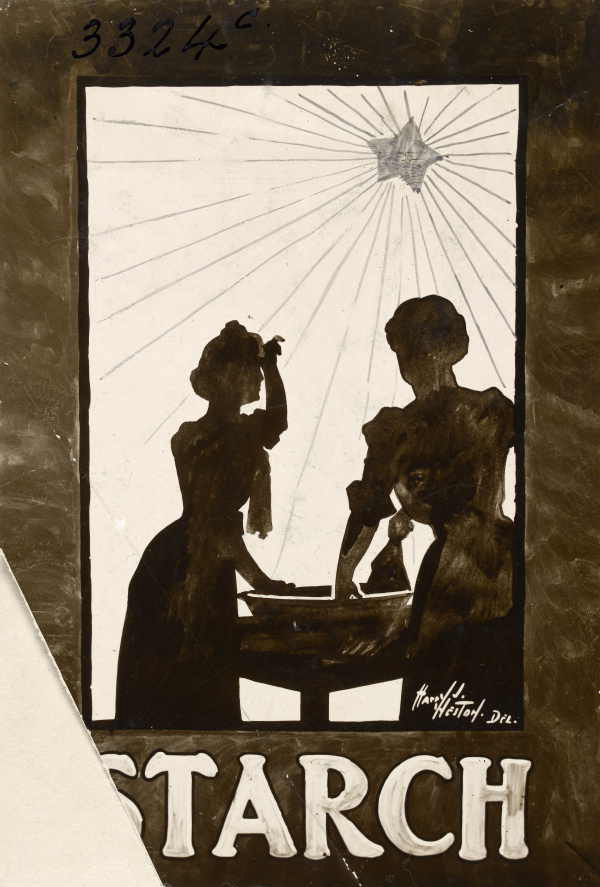

Sydney's first generation of advertising professionals emerged in the first years of the twentieth century. Thomas A Miller's eponymous agency emerged around 1902. The pioneering agency offered a complete service – buying space, writing copy, and, where possible, producing illustrations. Other full service agencies, such as the Weston Company, quickly followed. [media]Its founder, commercial artist Harry J Weston, soon sold out to Claude Willmott and John Norton. Weston then worked in the Bulletin's advertising department before establishing another agency with the photographer Walter Burke in 1908. It published the Reason Why, one of the first journals 'devoted exclusively to advertising problems'. [7] The commercial work by the Smith & Julius studio similarly provided a link between eminent artists and the fledgling advertising industry. [8]

Leaving the Miller agency in 1904, 'Billy' Richards bought out the Weston Company's new owners. His perseverance, integrity and good humour persuaded reluctant firms to use his services. When he retired from the agency in 1970 at the age of 92, Richards still held some of the accounts he had secured during his earliest days.

An advertising industry was forming around Sydney's growing number of advertising agencies. They formed the New South Wales Ad Men's Institute in 1917, and three years later it hosted the second Convention of Australasian Advertising Men. The gendered titles accurately reflected the composition of the industry. During this time and, indeed, for decades to come, the women working in advertising were generally restricted to secretarial or, more famously, artistic work. [9] Margaret Preston, Thea Proctor, and Hera Roberts all produced commercial works for the advertising industry. In addition to advancing the interests of the industry as a whole, the 1920 convention brought together two local admen – George Patterson and Norman Catts. As Catts–Patterson, they became the city's leading agency. Holding major accounts also enabled them to establish lucrative networks within the city's business and arts communities. [10] [media]Like the rest of the advertising industry, Catts–Patterson was also riding high on Sydney's boom of the 1920s.

The booming 1920s

The 1920s boom propelled Sydney into the position of the nation's premier advertising city. The media's increasing dependence on advertising revenue meant that advertising agencies were well positioned to establish themselves as key component of Sydney's media industry. The advertising industry's fortunes were also aided by the increasing number of large advertisers basing themselves in Sydney. By the decade's end, these companies had formed the Association of Australian National Advertisers to protect their interests. With the largest consumer base and a growing manufacturing sector, Sydney began to attract interstate agencies, particularly those with national and international clients. It was also luring international agencies. The Goldberg Company from New Zealand was the first to arrive, establishing a Sydney branch in 1924 before relocating its headquarters to Sydney in 1927. The American firm J Walter Thompson arrived shortly afterwards. The Depression-led closure of its Melbourne headquarters, coupled with opportune acquisitions of international accounts, saw the Sydney office become the multinational agency's sole Australasian branch. [11]

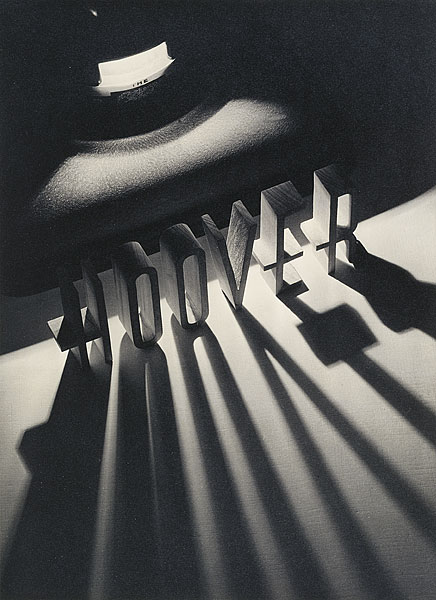

Commercial artists were also aided by the interwar expansion of Sydney's advertising industry and the improved printing technology utilised by the press. Walter Jardine was perhaps the most famous commercial artist of this generation. After a stint in the US, he began working freelance in 1928. [12] [media]His artwork for Akubra hats, Arnott's biscuits, and Tooth's beer was particularly noteworthy. With their specially commissioned advertisements, the lavishly illustrated journals Art in Australia and The Home enabled these artists to blur the line between art and commercial work.

Depression and war

[media]Advertising expenditure slumped during the Depression. Only the most dynamic agencies survived. Regaining ground in the mid-1930s, the industry received a timely boost from the growing popularity of radio. Commercial stations such as 2UE and 2GB were soon utilised by leading agencies and advertisers. Producing spot announcements and full programmes for clients, the advertising agencies became intimately involved with the local radio industry. [13] J Walter Thompson, for example, created the long-running serial Dad and Dave as well as the Lux Radio Theatre. The production of such programmes in conjunction with the revenue derived from traditional forms of advertising served to strengthen the advertising industry and reinforce the media's dependence on it. The decade also saw other changes. In 1934 Patterson acrimoniously split from Catts to head the George Patterson agency. Catts–Patterson lost its pre-eminence while George Patterson went from strength to strength.

The recovery and gains made by the advertising industry from the mid-1930s were curtailed by World War II. With rationing and restrictions impeding consumption, wartime advertising was compelled to sell the advertiser's brand rather than its products. Sydney's wartime brownouts provided another frustration. [media]Since the 1920s, neon lights had enabled advertisers to make their outdoor advertising work 24 hours a day. Brownouts halved their effectiveness. The Commonwealth government became the nation's largest advertiser in the war years, and Sydney's largest advertising agencies offered their services. As the War Effort Publicity Board, they created and coordinated the government's publicity campaigns. [14] [media]Newsprint shortages led to radio becoming the main advertising medium. Here, Patterson's business acumen came to the fore. Creating the Colgate–Palmolive Radio Unit, Patterson reached audiences well beyond Sydney. With Jack Davey as executive producer, director, writer and star, the Unit and its highly popular programmes were a spectacular success – cementing the relationship between show business, national advertising, and Sydney.

Postwar growth

The end of World War II marked the beginning of a new age – for advertisers, agencies, and consumers alike. With rations and restrictions becoming a thing of the past, Sydneysiders excitedly anticipated the opportunity to buy the products that advertisements had long promised them. Announcing that this was the 'age of accumulation', the advertisements placed by the Daily Telegraph in the advertising industry journal Newspaper News demonstrate that the industry was well aware that consumers' pent up desires would prove highly profitable. [15] The image of a house loomed large and the advertising industry actively encouraged Sydneysiders to realise the great Australian dream. Once consumers acquired their homes, new dreams were sold to them: a Holden for the driveway, a Silent Knight refrigerator for the kitchen or a Victa mower for the backyard. The advertising industry was also enjoying the continuation of commercial radio's golden age into the 1950s. George Patterson's Jack Davey now battled it out with J Walter Thompson's Bob Dyer for the prize of Sydney's favourite quizmaster. [16]

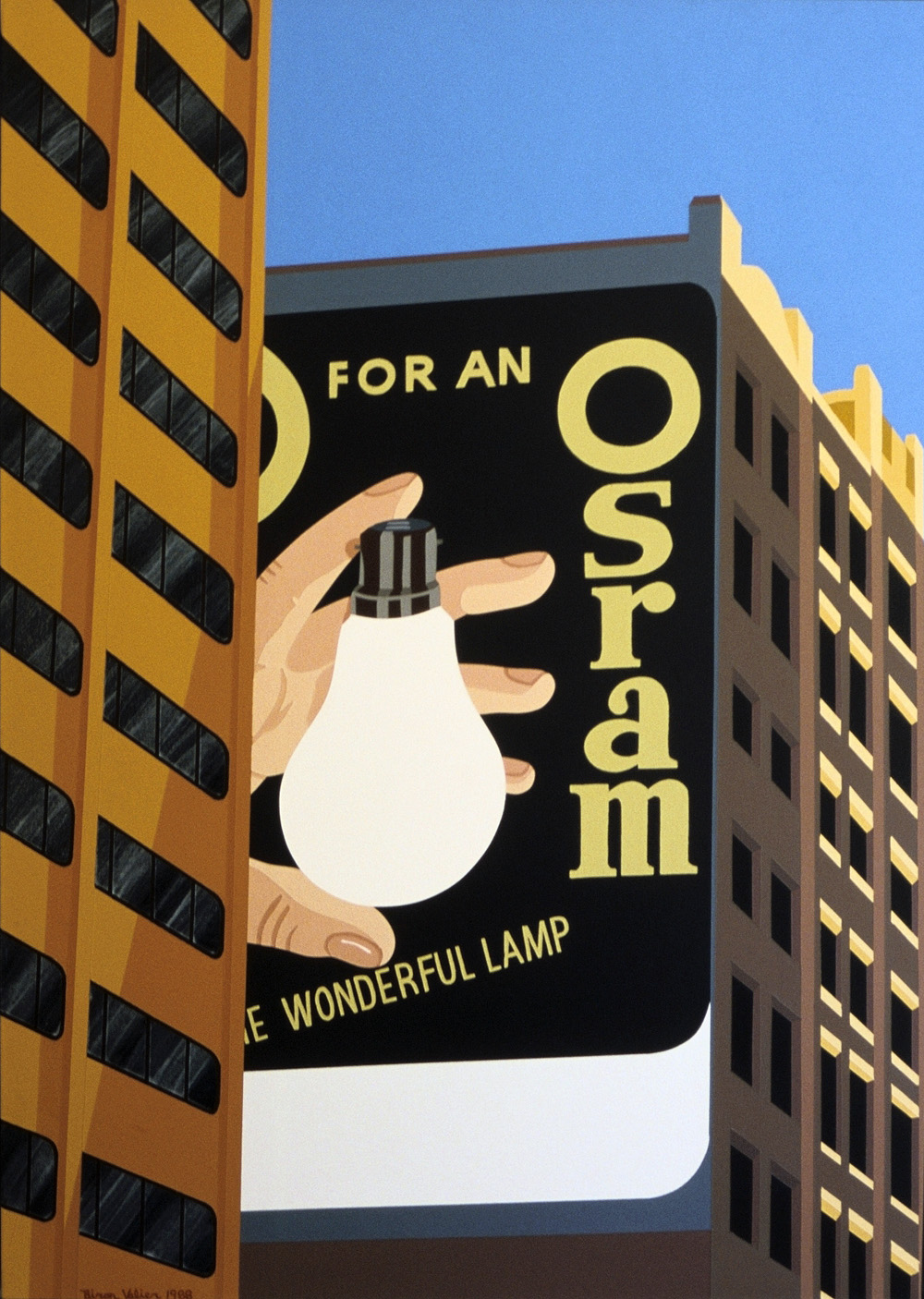

[media]Neon signs made a dazzling return in the 1940s and 1950s – as evidenced by the famous sign above Sharpie's Golf House in Elizabeth Street. [media]Since 1958 the sign's golfer has been chipping a ball into a hole. By the end of the century, four decades of exposure had left the sign in disrepair and its owner planned to dismantle it. A public campaign saved it from this fate and it now enjoys heritage protection. [17] [media]Other noteworthy outdoor signs were those for Axminster carpets and Taubman's paints that adorned Railway Square in the1960s.

The modern age

[media]When TCN 9 broadcast Australia's first television commercial in 1956, Sydney's advertising industry boasted that it had entered the modern age. In addition to attracting further advertising revenue, television brought Sydney to the attention of the world. Hansen Rubensohn sold out to McCann Erickson in 1959, becoming the first of many Sydney agencies to sell out to overseas interests. [18] Australia's booming economy attracted more international corporations, which tended to gravitate towards Sydney. Sydney's bustling new business sector and lifestyle were as much a drawcard as its proximity to key Asian and the Pacific markets. Aspiring advertising agents from interstate and beyond increasingly flocked to Sydney with the hope of making it big. As property and rental prices in the CBD increased, the advertising industry concentrated itself in North Sydney. Local restaurants and pubs profited handsomely from the industry's notoriously long and often boozy lunches.

[media]Erected in 1974, the iconic Coca-Cola sign at the intersection of William Street and Darlinghurst Road (dubbed 'Gateway to the Cross') was established as, and still remains, the largest billboard advertisement in Sydney. Dominating the local landscape, the billboard symbolised the new order in Sydney's advertising industry, where the giant transnational agencies and their clients reigned supreme. Transnational agencies demanded that staff at their newly acquired local branches strictly adhere to the customer service and marketing strategies devised by the head office. While these strategies modernised local agencies, they also generated frustration in the ranks. Sydney's most creative and energetic ad men and women opted to open their own agencies. John 'Singo' Singleton was one of the first pioneers. Having served his apprenticeship with local and multinational agencies, Singleton opened his SPASM agency in 1968. His accounts were largely local Sydney retailers but Singo's understanding of his audience enabled him to reach out to the entire nation. [19] Rather than using prim presenters, Singo celebrated the voice and image of the average bloke from western Sydney. One of his most successful advertisements was for David Holdings wholesalers. It simply outlined the retailer's prices before repeatedly chanting the catchphrase 'Where do you get it?' Identifying such loud and crude appeals with Sydney, critics derided it as 'ocker' advertising.

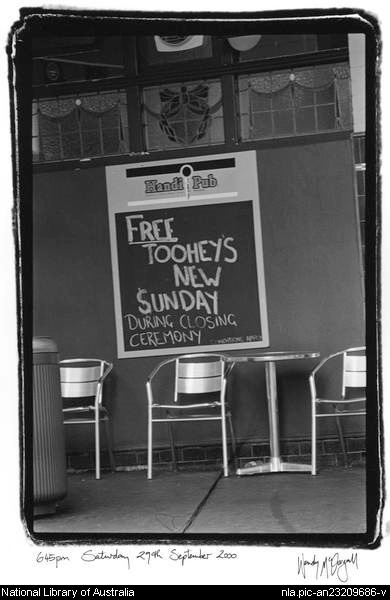

[media]As ocker advertisements lost their novelty, the Darlinghurst-based Mojo agency began to produce advertisements that revelled in their Australianness. Formed by Alan 'Mo' Morris and Allan 'Jo' Johnston in 1975, Mojo combined good ideas with catchy jingles to produce such anthems as 'I feel like a Tooheys or two' and 'C'mon, Aussie, c'mon'. Mojo soon became the largest locally owned advertising agency. In 1986 it merged with another Australian owned agency, MDA, to form Mojo MDA. Not content with having the third largest billings in Australia, the self-proclaimed 'Aussie battler' took on the world by opening offices in Britain and the United States. Sydney's advertising scene was equally positive. While George Patterson still dominated, the local industry was thriving, causing some Melbourne-based agencies, like The Campaign Palace, to relocate to Sydney.

Advertising and the arts

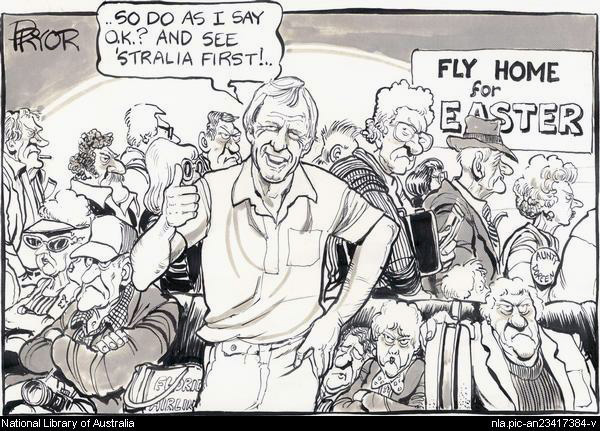

Throughout these postwar decades, the advertising industry continued to support and nurture the arts in Sydney. Consistent pay continued to draw artists to the advertising agencies. Brett Whiteley's advertising career in Lintas's art department, for example lasted three years, while Ken Done spent some 20 years in the industry. For those whose gift lay with words, copywriting provided a lucrative form of training. Having spent 34 years in the advertising industry, Bryce Courtenay is perhaps Sydney's most famous copywriter turned author. [20] Responsible for such iconic advertising characters as Louie the Fly and Mr Sheen, Courtenay divided his final years in the industry between advertising and writing his best-seller The Power of One. His subsequent career as a full-time author would prove to be even more lucrative than his years in advertising, a rare feat indeed. Television commercial production provided another key training ground for Sydney's arts community. Aspiring film directors, such as Bruce Beresford, initially gained their skills working on advertisements for local television. Actors also benefited from their brief stint in advertising. Elle McPherson's bikini-clad appearance in a commercial for Tab cola helped launch her modelling career. [media]Paul Hogan's success with Winfield cigarettes saw him become the international face of Australia, advertising Foster's Lager to Britons before selling Australia to the Americans.

Challenges to the industry

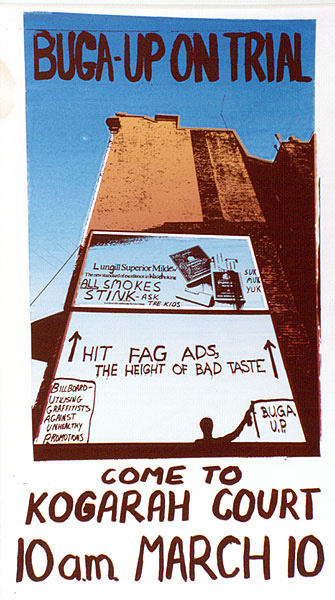

The increasing number of advertisements vying for consumers' attention, not to mention the industry's abundant wealth, began to attract some unwelcome scrutiny. The Australian Consumers' Association had been launched in Sydney in 1959 with the aim of helping consumers make informed choices. By the 1970s, it was educating consumers about their rights. [21] Emboldened consumer activists now challenged the industry for the images it conveyed. [media]Feminists castigated the industry for its sexist stereotyping of women whilst groups such as Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions (better known as BUGA UP) regularly defaced cigarette and alcohol billboards across Sydney in order to prevent such industries from advertising their wares.

The advertising industry's long boom finally drew to an end in the late 1980s when the recession struck. This was the first time that advertising expenditure had fallen since the Depression. North Sydney restaurants were the first to feel the pinch, as anxious admen and adwomen spent their lunchtimes working at their desks. Retrenchments became commonplace as each agency sought to streamline its operations. The crisis soon caught up with Mojo MDA. It had become overstretched and in 1989 Sydney waved goodbye to its first global agency. [22] [media]In advertising's increasingly globalised world, Sydney hoped to establish itself as a regional hub. While it was the Australasian region's advertising centre, competitors such as Hong Kong and Tokyo kept Sydney's global aspirations in check. Sydney advertising chiefs had scant impact on any deals made in New York or London. They could wake up one morning to discover that an overnight decision taken in one of these international headquarters meant that their agency was now allied with a former competitor as part of a new global network.

Over the 1990s, advertisers increasingly fragmented their accounts, creating new agencies that specialised in particular areas of advertising (such as media buying or creative design). [23] Pay TV and the internet further fragmented the advertising industry while empowering the advertiser. With the agencies becoming smaller and more competitive, advertisers succeeded in establishing themselves as the dominant players in the advertising scene. The Association of Australian National Advertisers thus succeeded in reducing the restrictions on Australian content for advertisements broadcast on commercial television. [24]

The new century

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the advertising industry was one of the city's most idiosyncratic and, indeed, visible industries. In some ways, it appeared to have changed little since the beginning of the twentieth century. Advertisers dominated the industry while fragmentation meant that the advertising agencies serving them were likely to be smaller and more specialist operations. It was still a cut-throat business, but it also provided opportunities for creative Sydneysiders to hone their talent and to earn healthy salaries. Although the industry's 'home' was still in North Sydney, agencies could now be found across the city. However, significant changes had also occurred. Globalisation continued to affect the industry and its operations. While transnational advertisers and agencies dominated the local industry, their global networks were also opening new opportunities for Sydney-based staff to reach international audiences. In 2003 Baz Luhrmann directed a commercial for the French perfume Chanel No 5. Filmed at the recently built Fox Studios, the commercial 'starred' fellow Sydneysider Nicole Kidman and was described as the most expensive advertisement ever made. [25] The internet similarly provided another avenue for Sydney agencies to reach an international audience.

In the process of selling its wares, it seems that advertising and the industry behind it has also become an essential symbol of Sydney. Functioning as outdoor advertisements, the branding of cultural events and the renaming of sporting grounds illustrate the city's ongoing ties with its commercial sector. Heritage listings for prominent outdoor advertisements indicate that Sydneysiders also feel an abiding, if nostalgic, relationship with advertising.

Advertising Sydney

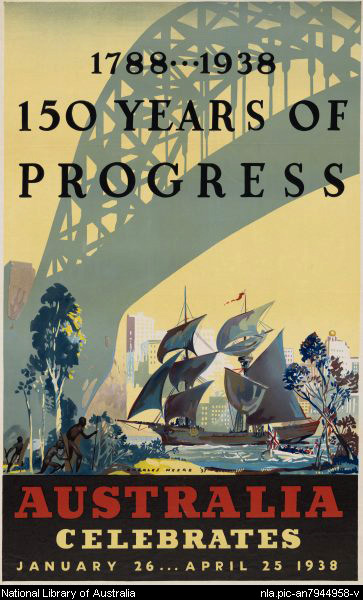

In advertisements aimed at local and international audiences, Sydney's iconic landmarks have become shorthand symbols of contemporary urban Australia. Aimed at an international audience, the posters created by the Australian National Travel Association depicted Sydney as an exotic yet modern destination. A 1929 poster celebrated Bondi Beach's urbanity as well as its golden sands and pristine waters, while posters advertising Australia's sesquicentenary celebrations used the city to denote the nation's progress. [26] The Sydney Harbour Bridge was the city's first manmade iconic landmark, appearing in advertisements long before its opening in 1932. Recognising the bridge's symbolism, one cigarette advertisement declared: 'We are not going to try to have this announcement placed on the bridge, feeling that even a “CAPSTAN” advertisement would be somewhat out of harmony with the dignity and impressiveness of this magnificent structure'. [27] The regulation that no advertising appears on the bridge still remains. In addition to symbolising strength and hope, the bridge was used by tourism authorities to represent a modern Australia to the world. After the Opera House was finally opened in 1973, the two icons have become almost inseparable. [media]In the 1980s Paul Hogan welcomed Americans from the top of the bridge with the Opera House in the background, while the more recent 'Where the Bloody Hell are You?' campaign featured both icons lit up at during the New Year's celebrations. The icons also appeared throughout the coverage of the 2000 Sydney Olympics, an event that similarly functioned as an advertisement for Sydney and, indeed, the rest of the nation.

References

Robert Crawford, 'But Wait, There's More...': A History of Australia's Advertising Industry, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2008

Amanda McLeod, Abundance: Buying and Selling in Postwar Australia, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2007

Notes

[1] RB Walker, The Newspaper Press in New South Wales 1803–1920, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1976, p 3

[2] Beverley Kingston, Basket, Bag, and Trolley: A Short History of Shopping in Australia, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1994, p 9

[3] RB Walker, The Newspaper Press in New South Wales 1803–1920, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1976, p 210

[4] RB Walker, The Newspaper Press in New South Wales 1803–1920, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1976, p 213

[5] Robert Crawford, 'The Quest for Legitimacy: The Growth and Development of the Advertising Industry in Australia, 1900–1969', Australian Historical Studies, no 124, October 2004, pp 357–58

[6] Brian Tyquin, 'Signs of the Times', Advertising News: Golden Anniversary Book 1928–1978, 17 November 1978, p 46

[7] Reason Why, vol 1 no 1, July 1908, p 9

[8] Nancy DH Underhill, 'Smith, Sydney George Ure (1887–1949)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 11, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988, pp 662–66

[9] Robert Crawford, 'But Wait, There's More...': A History of Australia's Advertising Industry, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2008, pp 150–67

[10] Robert Crawford, 'But Wait, There's More...': A History of Australia's Advertising Industry, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2008, p 40

[11] HR Wearing, 'The Establishment of J Walter Thompson in Australia', International Office Histories – Australia 1963, Nov, Sidney Ralph Bernstein, Box 5, J Walter Thompson Company Archives, Rare Book, Manuscript and Special Collections Library, Duke University, North Carolina

[12] Anne-Marie Gaudry, 'Jardine, Walter Lacy (1884–970)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 14, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1996, pp 559–60

[13] John Potts, Radio in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1989, chapter 5

[14] Robert Crawford, 'Nothing to Sell? – Australia's Advertising Industry at War, 1939–1945', War and Society, vol 20 no 1, May 2002, pp 99–124

[15] Newspaper News¸ November 1946, pp 16–17

[16] Lesley Johnson, 'Davey, John Andrew (Jack) (1907–1959)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 13, Melbourne University Press, 1993, pp 574–575.

[17] 'Sharpies Golf House Sign (The Golf House)', http://www.heritage.nsw.gov.au/07_subnav_02_2.cfm?itemid=%095053378, accessed 10 December 2007

[18] Keith Cousins, 'What Lured Them to Australia?', Advertising News: Golden Anniversary Book 1928–1978, 17 November 1978, pp 68–69

[19] Robert Crawford, '“Anyhow … Where d'yer get it?”: Ockerdom in Adland Australia', Journal of Australian Studies, no 90, 2007, p 6

[20] Scott Morton, 'Escape Artists', AdNews: The Legends of Advertising, 30 October 1998, p 103

[21] Amanda McLeod, Abundance: Buying and Selling in Postwar Australia, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2007, p 153

[22] B&T, 17 March 1989, p 29

[23] B&T, 4 April 1997, p 28

[24] Robert Crawford, 'But Wait, There's More...': A History of Australia's Advertising Industry, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2008, pp 237–249

[25] Chanel No 5, http://www.bazthegreatsite.com/chanel.htm, accessed 10 December 2007

[26] Joy Eadie, 'Pic Poster Z156 – Presenting Progress' NLA News, December 2006, pp 3–6

[27] Newspaper News, March 1932, p 9

.