The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Long Bay prison

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Long Bay prison

The Long Bay prison complex is significant as the only prison in Australia to be planned with separate prisons for men and women. It is an important example of the work of the New South Wales Government Architect's Office under Walter Liberty Vernon. It was used continuously as the principal prison complex in the state for over 80 years.

Long Bay Correctional Centre is situated on a coastal ridge at Malabar in the municipality of Randwick. The site, about 12 kilometres south of Sydney, was selected in accordance with the views of John Howard, the English prison reformer of the 1770s. He believed that prisons should be located away from towns, preferably on the rise of a hill, to receive the full force of the wind. It was designed by Walter Liberty Vernon and reflected the penal system advocated by William Frederick Neitenstein, the comptroller-general of prisons from 1896 to 1909. Neitenstein believed in 'restricted association', which segregated prisoners and aimed to avoid the corruption of young or first-time offenders.

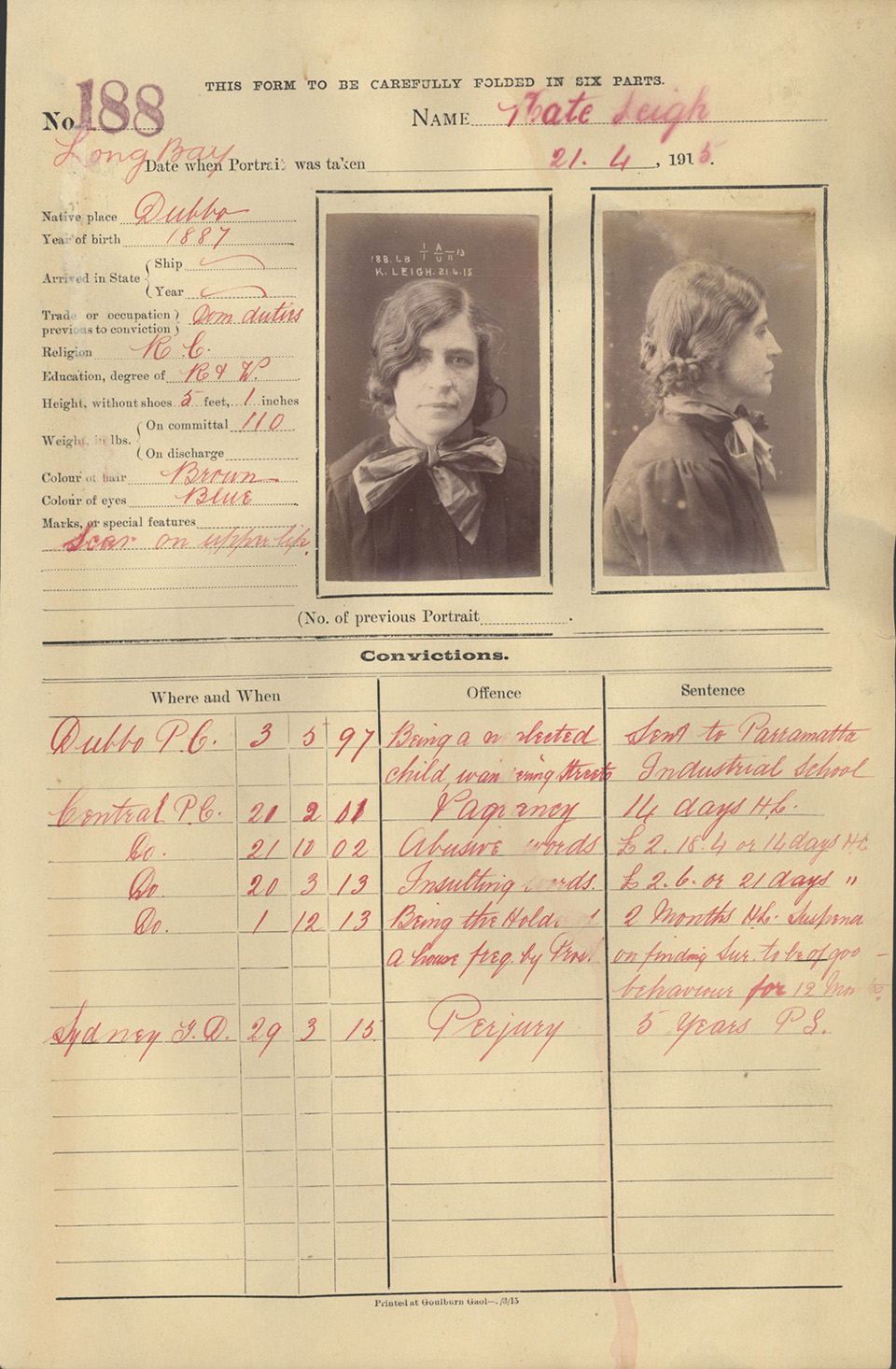

The female reformatory – a model prison

Priority was given to the female reformatory and construction began in 1901. This was regarded as a model prison, founded on high-minded therapeutic lines devised by Rose Scott and other penal reformers. When it opened in August 1909, the new block, with its Federation Gothic entrance block, elegant glazed timber octagon and radial design, was highly praised as one of the few purpose-designed women's prisons in the world. The daily average occupancy in the female prison in 1909 was 124, growing to 199 in 1916 but declining after that. Two recurrent inmates during the 1930s [media]were inner-city crime queens Tilly Devine and Kate Leigh.

By 1937 there were only 42 occupants in 276 cells, a decline attributed to the success of the reformist philosophy. In 1936, a women's Cottage Block was built to segregate female first offenders from the 'hardened' inmates of the reformatory. It was demolished in the 1960s for a new boiler house.

The male penitentiary

The male penitentiary was the first jail in New South Wales to cater especially for petty offenders. Though less elaborate than the female reformatory, it took longer to complete and was opened in 1914. The brick complex consisted of a separate entrance block, six two-storey cell wings, a debtors' prison, workshop, hospital and observation ward. The original 1899 plans showed seven wings of back-to-back cells with external doors, but only four were built. The other three were replaced by two wings of galleries, indicating that usage had changed to low-security accommodation of all classes of prisoners, eroding Neitenstein's elaborate prisoner classification system. The back-to-back cells were used until recently and some examples of this rare experimental design remain.

For the first time, attention was paid to prisoners' amenity with cell sizes, electric lighting, ventilation sources and the location of sanitary facilities being given priority. A baker's oven was installed in the kitchen in 1915, beginning the long tradition of bread-making at Long Bay. The manufacture of concrete blocks for building sites became another important ongoing activity. Between 1915 and 1918, prisoners constructed a chapel with ornate timber joinery, stained glass and polished marble decorations.

Building materials were transported to the site by steam tram on the new La Perouse tramway. The line was electrified in 1906 and, until 1950, prisoners were conveyed in compartmented prison cars directly from Darlinghurst police station to the birdcages at the Entrance Block.

Overcrowding and unrest

By the 1920s, Long Bay was receiving over 70 per cent of all jail entries, including remand inmates, and was overcrowded. Additional timber huts were erected to accommodate the overflow. In 1962, a new female reformatory was opened to the north-east of the main prison. The initial intake was 78 although the five cell wings had accommodation for 240.

A 1946 report confirmed overcrowding at Long Bay. Part of the under-utilised women's prison was taken over in 1945 and in 1962 the old reformatory was resumed by the male prison, now called the State Penitentiary. This became the principal reception centre for remand prisoners and all committals in the larger Sydney area, as well as the main hospital and mental observation centre for the state. Even with the additional space, it was overcrowded, with 1,244 prisoners in 1965 in an area more suitable for 815, and was regarded as a depressing and inhuman place. In 1967, the first purpose-built remand centre was opened with places for 224 inmates.

From 1968, work began in secret on a maximum security block to be called Katingal, an Aboriginal word meaning separation from social control. It was designed to eliminate physical contact between inmates and staff and also between inmates and the outside environment. Despite the repressive environment within the white windowless block, prisoners still managed to escape or riot. Public criticism of this isolated regime led to the Nagle Royal Commission into New South Wales Prisons in 1978 that recommended closure of the facility.

The women were moved to the Mulawa Correctional Centre at Silverwater in 1969 and their reformatory was converted into a training centre, later used to hold minimum security inmates. The 1970s was a period of prisoner unrest and industrial action by staff. On Christmas Day 1978 a riot by prisoners led to the workshops being burnt down.

Long Bay since the 1980s

Since the 1980s, additional facilities and prisoner activities have been introduced at Long Bay. Specialist buildings have been constructed and, after a series of name changes, the complex emerged in 1993 as the Reception and Industrial Centre. In 1997, the Metropolitan Remand and Reception Centre opened at Silverwater, becoming Australia's largest correctional centre. Short-sentence prisoners remained at Long Bay, while those with longer sentences were often transferred to country prisons.

Enhanced security technology including motion detectors and video surveillance has not been completely successful in preventing embarrassing escapes. In January 2006, the maximum security prisoner Robert Cole escaped from Long Bay by losing weight, removing bricks from his hospital jail cell and squeezing his way through the gap in the brick wall.

References

'Crash diet prison break out', Sydney Morning Herald, 18 January 2006

New South Wales Department of Public Works and Services Heritage Group, 'Long Bay Correctional Complex: Conservation Plan', Department of Corrective Services, Sydney, 1997

Terry Kass, 'Long Bay Complex 1896–1994: A History – Final Report', New South Wales Public Works, 1995

John Ramsland, 'Dulcie Deamer and the Women's Reformatory, Long Bay', Journal of Interdisciplinary Gender Studies, vol 1, no 1, 1995, pp 33–40