The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

New Year's Eve

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

New Year's Eve

New Year's Eve in Sydney is an iconic event. When thousands of revellers gather near Sydney Harbour, the city's great emblems are all prominent. The Opera House and the Harbour Bridge frame the evening's climax: fireworks at both 9 pm and midnight announce and celebrate the arrival of the New Year. The ritual is so embedded that it seems that it must always have been thus.

As symbolically powerful as the harbour, the bridge and the Opera House are for New Year's Eve now, the celebration's presence by the harbour has a surprisingly short history. The first New Year's Eve as we know it was 31 December 1976. The first formal New Year's Eve celebration in Sydney ever, properly speaking, was 80 years earlier, on 31 December 1896.

From New Year's Day to New Year's Eve

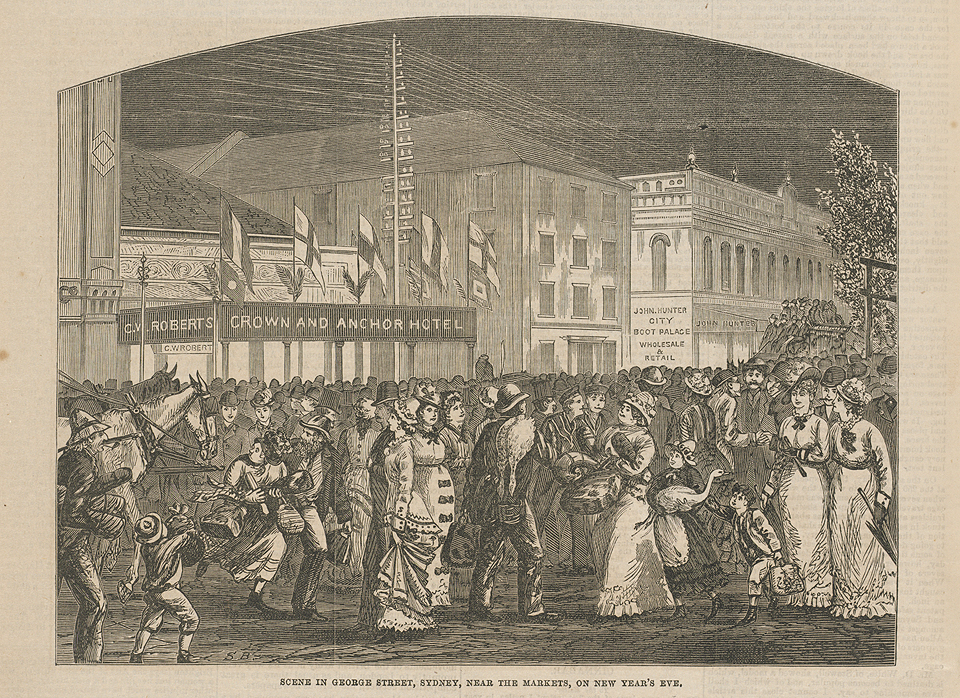

A new, [media]particularly urban kind of celebration defined the New Year's Eve leading into 1897, but small celebrations did happen before that. One newspaper reported bonfires at Pyrmont and Balmain, as small groups of friends saw in 1868. 'The vessel lying in Circular Quay was prettily illuminated.' At midnight, ships' bells and church bells all tolled and 'occasionally a rocket shot high in the air'. Strangers greeted each other with 'a happy new year to you'. The streets were a little more crowded than normal, but not rowdy. [1]

New Year's Day was more important then. Celebration of New Year's Day had entered Australian custom via the Scottish festival, Hogmanay. [2] This connection was still evident in the popular Highland Gathering at the Sydney Cricket Ground on New Year's Day. [3] In newspapers and official records, while New Year's Day was described frequently, the evening before it was barely mentioned at all.

New Year's Day had increased in prominence as a day of pleasure in the nineteenth century. Picnics were traditional, but public and commercial events were also important. Musical performances and vaudeville were held at Coogee and Bondi aquariums. Ballroom dancing was held at Clifton Gardens from 10 am to 10 pm. Coogee beach also hosted a 'startling' Hall of Illusions. It was a very similar holiday to Boxing Day. [4]

Celebrating at night – the importance of good lighting

Cities took a long time to truly conquer night. [5] It was only in the 1890s that lighting technologies existed that made it possible for large crowds to be safely outdoors at night: it was still gaslight, although electricity was just around the corner. But a new type of gaslight called incandescent or arc lighting had literally changed the ways that Sydney residents viewed the night. [6]

Incandescent gas lamps were much brighter than the earlier type. In this light, human eyes, using retinal cones, saw as in daylight rather than with retinal rods, as with earlier forms of gaslight and at night. [7] When this new lighting was installed in the streets of the central business district, celebrating New Year's Eve there seemed especially attractive. The city council's experiment with incandescent gaslights during 1896 led to the first real New Year's Eve on 31 December 1896. [8]

The First New Year's Eve

On 31 December 1896, more people celebrated New Year's Eve in the streets of Sydney than ever before.

It was the first time, according to newspaper reports, that night-time street revellers identified themselves as members of a crowd, cohesive and urban, belonging in the city for New Year's Eve. As the Sydney Morning Herald said

Many thousands of people marched through while others clustered about the principal streets until midnight, which were more brilliantly illuminated up till within a few minutes of the advent of the new year than they had ever been before to so late an hour. [9]

Shops generally stayed open, with their shop fronts and verandah posts still decorated, from Christmas, with bushes and lit with Chinese lanterns . [10] 'George-street from King-street, right on to Brickfield-hill, was brilliantly lighted owing to the number of shops that remained open for business'. [11]

King Street held the biggest crowd on the first New Year's Eve. This was due to its proximity to the arcades, which were full to overflowing with straw-hatted office workers. At the Haymarket end of George Street were the working people. The Queen Victoria Markets, on the other hand, were filled with 'irresponsible youths…evidently factory hands'. Both sexes were present and, according to newspaper reports, as apparently irresponsible as one another. They were 'somewhat free in the interchange of greetings'. By contrast, the 'better dressed and quieter people' in the city 'professed to be profoundly shocked by the antics of the revelling minority' as they paraded what was known as 'the block'. [12]

[media]The arcades were clearly the place to be. [13] On the New Year's Eve that saw in 1897, the Strand Arcade, the Sydney Arcade and, to a lesser extent, the Imperial Arcade, were so crowded their proprietors had to close the gates (as they do at the Opera House now) to prevent catastrophe, and 'the ejected ones went to swell the crowds in George and King Streets'. [14]

The public was especially conscious of time too, for Australia had just changed from local time (measured by the sun) to international standard time (measured from Greenwich) in 1895. [15]

At midnight, the crowd descended on the General Post Office in Martin Place: its clock tower had been completed just five years earlier, and extensions to the building had been done during the year. It was the highest point in Sydney. It defined and gave focus to the centre of the city, and was therefore the focus of New Year's Eve. [16] The monumental clock was modern and industrial, a contrast to the old church bells that had formerly signalled in the New Year. No longer reliant on the churches, the modern urban crowd could literally watch the New Year begin.

Trouble on New Year's Eve

The 1897 scene was repeated for several years. But in 1908, things got out of control. New Year's Eve was generally a fairly disreputable night – and this was part of its appeal. In particular, people were noisy. They carried musical instruments, pots and pans to bang, kazoos to blow in others' ears. Many normally respectable people imitated the behavior of the larrikins who dominated the city on Saturday nights.

Eventually, the larrikins themselves saw it as an opportunity for outrageous behaviour. They targeted the women in the crowd. Sexual harassment and possibly violence is implied in the reports that were too prudish to describe in detail what the newspaper journalists saw – it was too terrible to print, they said. [17]

The 1908 crowd was further terrorised by larrikins carrying 'explosive sticks': fairly thick canes with metal points that made a small explosion when struck on the ground. [18] The police found the crowd unmanageable. They were unable to protect women from harassment or stop the terrors inflicted by the explosive sticks. As a result, people wanted action.

The Town Clerk investigated the city's legal position and concluded that existing laws were sufficient to arrest those who had misbehaved on New Year's Eve. Police instead arrested the man who had imported and sold the exploding sticks, Michael Albert. He protested that they were a harmless novelty: they may have frightened members of the crowd, but they did no actual harm. Customs had investigated and approved their import. Albert was nevertheless fined £5 under the Explosives Act for importing a dangerous substance. [19]

Although there were no more explosive sticks, New Year's Eve continued to be a dangerous and disreputable night.

Bonfires were a dangerous problem in streets that were crowded and rowdy. Revellers would boo and hiss the firefighters who came to put them out, and would relight them once they went away, [20] something that used to happen on Empire Night as well. [21] In one dreadful instance, a police officer was pushed into a bonfire that he had insisted must be extinguished. [22]

Fire was reported as a problem on New Year's Eve up until the 1960s, though there was an attempt in 1909 by the City Council to minimise it, by asking shops to 'stop the silly custom of decorating shop fronts and verandah posts in the city with bushes at Christmas'. Police had informed the Council that:

The bushes, which dry in a few days, become highly flammable…A good deal of it gets into the hands of mischievous boys and is the principal cause of the dangerous bonfires on New Year's Eve. [23]

'The quietest New Year's Eve ever'

In times of crisis or rain, the newspapers would describe it as the 'quietest New Year's Eve ever'. [24] The newspapers then spoke of the bonfires with sad nostalgia:

Apparently the old year had very few friends. There were none who seemed to mourn its passing….In the old days, the display of merriment may have been gayer and more abandoned. There are no longer bonfires and street parades to greet the New Year. No longer do folks tear down the bushes, make merry in the glare of their blazing masses. [25]

The Great War and the Great Depression – or rain – inhibited Sydney's desire to celebrate. With the arrival of American soldiers in World War II however, the longing to celebrate New Year's Eve increased. It was also at this moment that the centre of the action moved to where the soldiers were – Kings Cross.

New Year's Eve in Kings Cross

On 31 December 1939, authorities were completely taken by surprise when the New Year's Eve crowd suddenly appeared in Kings Cross. [26] It rapidly gained a sense of tradition and remained the festival's centre until the introduction of fireworks at Circular Quay in 1977. By 1942 the inner-city locale was hailed as the 'principal centre of New Year celebrations'.

At this point, the Herald started reporting New Year's Eve with more affection than ever, concentrating on the funny things that were observed over the course of the evening. Rather than being shocked, as they had been in 1897, reporters tended to portray the event as one in which Sydneysiders had a single night for indulgence in slightly disreputable activity. This 1950 report is a good example:

One girl stripped off her frock and began dancing in a French bathing suit. A 16-stone woman turned Catherine wheels until the police stopped her. At Manly, a middle-aged man stood near the bow of the ferry, a bottle in one hand and a paper cup on his head and a white handkerchief in his other hand, singing out: 'The name's Columbus'. [27]

In 1964 at King's Cross, someone commenced a new tradition by jumping into the El Alamein fountain. [28] It was hot. Swimming in the fountain seemed so sensible that police barely made any attempt to stop it that first time. But for years afterwards, a battle raged every New Year, between police trying to protect the fountain and the crowd trying to jump in. [29]

New Year's Eve goes official

In 1976, the Sydney Committee decided to reconstitute a failing Waratah Festival as the Festival of Sydney. [30] At the first meeting of its Programme Committee, they agreed that New Year's Eve should launch the new festival, a 'big bang affair'. Focusing on the harbour and adjacent areas, it would include a sail-past of decorated craft, music, and a 'spectacular fireworks display at midnight'. [31] With this, the Festival of Sydney made New Year's Eve official for the first time. Stephen Hall was its Executive Director from 1977 to 1994.

However, fireworks did not immediately distract the crowds from Kings Cross. It was not until 1987 that Kings Cross was described as the 'quietest' of the city's crowded spots. [32]

Cancelling New Year's Eve fireworks

New Year's Eve at the harbour had a troubled beginning. In 1980, street violence and the casualties of thrown beer cans led to ticket-only admission to New Year's Eve at Circular Quay the following year [33] – but this turned out to be so quiet that the Herald said:

The New Year and the Festival of Sydney did not exactly start with a whimper, but it hardly started with a bang. [34]

The 1980s was a decade where urban violence had increased generally, probably a result of widening divisions between rich and poor, a growing illegal drug trade and increasing numbers of homeless youth. [35] In 1985, Sydney police asked the Festival Committee to pay particular attention to the potential for violence on New Year's Eve. The Rocks was the key area to watch.

The Sydney Festival Committee considered a range of ideas to help reduce the potential for violence. They thought about placing fireworks in multiple locations so the crowd would not be concentrated at Circular Quay, and perhaps including an event in western Sydney. They speculated on whether television coverage might reduce the crowd somewhat. They decided definitely not to host any entertainment at The Rocks. Police warned that none of it would help.

Mr Howard, of Howard Pyrotechnics, suggested that if they were to display the fireworks earlier, the problem would be solved. The committee found it unthinkable. Midnight was the right time for New Year's Eve. [36] One member of the committee said that:

Generally, disorderly behavior and even violence is an accepted fact of New Year's Eve celebrations worldwide: and that it should increase from year to year in potential. Sydney was no exception to this fact. [37]

Fireworks went ahead for the New Year leading into 1986. Most were sorry.

The behavior of the crowd that gathered was frightening, with violence and much harassment. Many onlookers sought shelter in nearby hotels, 'fearing harm from the crowd congregated in The Rocks/Circular Quay area'. [38] In a meeting with the Police Commissioner, heads of Armed Services and heads of statutory authorities in August 1986, the 1986 New Year's Eve was described as 'that debacle'. [39]

Businesses in The Rocks wrote to the Festival Committee, begging that they cancel the next New Year's Eve fireworks. 'The threat of violence and harassment by the crowds generated there were alarming to the extent that they would consider boarding up their premises on future New Year's Eves'. Indeed, they were willing to pay the Festival to move the fireworks to around 8.30 pm on New Year's Day. [40]

Stephen Hall asked the Festival committee to delete fireworks from its program. However, fears that stopping 'such a well established and expected event as the Fireworks would result in a major loss of media' prevailed. The New Year's Eve midnight fireworks were repeated for 1987. Disaster struck: at The Rocks, some people in the New Year's Eve crowd were murdered. [41]

In 1988, the Bicentenary year, there were no fireworks at all for New Year's Eve. Police presence for the night was so heavy that the Herald could only describe it as 'dampening'. [42]

The Bicentenary

'It is recommended', wrote Stephen Hall to Barrie Unsworth, the New South Wales Premier in 1987, 'that New Year's Eve not be used as the launch pad for the Bicentennial Year':

Unfortunately in our society, New Year's Eve has become a night for drunken carousing and little else…In the past two years, near riotous behavior has been reported on New Year's Eve. [43]

Despite official festivities duly concentrated on New Year's Day in 1988, it was that Bicentennial year that returned some respectability to fireworks.

So many fireworks were displayed in 1988 that there is evidence that, by the end it was appearing a little tired. 'Yet more fireworks for Sydney', declared journalist Peter Robinson of the 1989 New Year's Eve, suggesting that in the previous year fireworks had become an unshakeable tradition of celebration in the city, which he paralleled to a more generalised 'illusion that such continuous artificial drama is in truth the reality'. [44]

From 1989 onwards, fireworks were embedded as the traditional way for Sydney to celebrate New Year's Eve, with two families dominating the provision of New Year's Eve fireworks in Sydney: the Howard family through Howard & Sons Pyrotechnic and Syd Howard fireworks, and the Foti family. [45] The safety of the crowds became so assured that New Year's Eve included an additional fireworks display at 9 pm for children.

2000 and beyond

No [media]longer just an item in the Sydney Festival committee minutes, New Year's Eve took on a life of its own: thick glossy operations manuals, concept plans, city plans and post-event reports were produced to manage an event that quickly became deeply entrenched in Sydney culture.

The celebration of the millennial New Year was expected to be an event to rival the Bicentennial Australia Day in 1988. The City of Sydney Major Events unit saw it as the 'culmination of four years of events leading up to the year 2000'. Very substantial fireworks were planned, spread over a larger than usual area to accommodate viewing from many parts of the harbour foreshores. A 'harbour of light' parade included tall ships and giant lanterns. Entertainment was planned at the Opera House, the Domain, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Darling Harbour, Circular Quay, The Rocks, and Pyrmont. [46]

However, as the year 2000 approached, Sydney was skeptical. The New South Wales government had been promoting the year 2000 for some years already, as part of the organisation of the Olympic Games, to be held in Sydney that year. 'In the weeks approaching New Year's Eve, it appeared cynicism might dominate', said the Sydney Morning Herald. Since the Bicentenary, 'fireworks' had accumulated meanings representative of the 'surface city' – the inauthentic tourist city, presented to the world as gleaming and successful, hiding its darker, sometimes violent and often exploitative 'true' character. [47] In the same spirit, the Sydney Olympics were cited as a good opportunity for a cheap airfare out. [48]

However, the success of the fireworks leading into 2000 affirmed New Year's Eve as a key Sydney event. World-class New Year's Eve celebrations are expected by the hundreds of thousands of Sydney residents and tourists who gather by the harbour each year. [49]

References

Australia Post, The City's Centrepiece: the history of the Sydney GPO, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1988

Graeme Davison. The Unforgiving Minute: How Australia Learned to Tell the Time, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1993

Hannah Forsyth, 'The energy of the city: Marshall Berman and New Year's Eve in Sydney', Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, 2008, 22 (2) pp 241–253

Hannah Forsyth, 'Making night hideous with their noise: New Year's Eve in 1897', History Australia (forthcoming) 2011

Peter Murphy and Sophie Watson, Surface City: Sydney at the Millennium, Pluto Press, Sydney, 1997

Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night: the industrialisation of light in the Nineteenth Century, Berg, Oxford, 1988

Yi-Fu Tuan, 'The City: its distance from nature', Geographical Review, 1978, 68 (1), pp 1–12

Notes

[1] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1868

[2] The Book of Days, W & R Chambers, London, 1881, p 29

[3] Sydney Morning Herald, 30 December 1897; Sydney Morning Herald 1 January 1930

[4] Dymocks Guide to Sydney & NSW, William Dymock Book Arcade, 1897, p45; Sydney Morning Herald, 23 December 1899

[5] Yi-Fu Tuan, 'The City: its distance from nature', Geographical Review, 1978, 68 (1), pp 1–12

[6] City Surveyor's Report on the Use of Incandescent Gas Burners in the City, Minutes of the Sydney City Council, 1896

[7] Wolfgang Schivelbusch,. Disenchanted Night: the industrialisation of light in the Nineteenth Century, Berg, Oxford, 1988, p 118

[8] City Surveyor's Report on the Use of Incandescent Gas Burners in the City, Minutes of the Sydney City Council, 1896

[9] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1897

[10] See letter from Sub-inspector to Superintendent of Police, forwarded to the Town Clerk in December 1909. City of Sydney Archives, CSA42797 Series 28 Item 1909/2848

[11] Letter from Sub-inspector to Superintendent of Police, forwarded to the Town Clerk in December 1909. City of Sydney Archives, CSA42797 Series 28 Item 1909/2848

[12] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1906. This information is not given in the 1897 report, but the rest of the detail is so similar it is reasonable to assume it was the same each time

[13] The arcades were exciting symbols of progress, modernity and consumer aspiration – ideas that all contributed to the excitement of New Year's Eve. Good economic times had led Sydney to build several arcades to accommodate many shops in smaller spaces. Between 1881–1892, over six arcades were built in Sydney. See General Note on Sydney Arcade, George & King Streets, Sydney, 1881 / Thomas Rowe, architect, State Library of NSW, Mitchell Library Album ID 823606, http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/item/itemDetailPaged.aspx?itemID=446981 Arcades had gained great popularity in the 19th century. As Walter Benjamin noted in the 1930s, one went to arcades to look at commodities and to be looked at – perhaps like a commodity. Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2002

[14] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1868

[15] Graeme Davison, The Unforgiving Minute: How Australia Learned to Tell the Time, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1993

[16] Australia Post, The City's Centrepiece: the history of the Sydney GPO, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1988, p 47

[17] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1908; 2 January 1908; 6 January 1908

[18] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 January 1908

[19] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 February 1908

[20] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1941; 1 January 1950; 1953; 1 January 1960;

[21] Stewart Firth & Jeanette Hoorn, 'From Empire Day to Cracker Night' in Peter Spearitt and David Walker (eds), Australian Popular Culture, Allen & Unwin, 1979, p 35

[22] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 January 1908

[23] Letter from Sub-inspector to Superintendent of Police, forwarded to the Town Clerk in December 1909. City of Sydney Archives, CSA42797 Series 28 Item 1909/2848

[24] For example Sydney Morning Herald 1 January 1906; 1 January 1917; 1 January 1924; 1 January 1930

[25] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1931

[26] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1940

[27] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1950

[28] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1964

[29] Eg. Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1965; 1 January 1970

[30] Descriptive Note, Function detail of the Festival of Sydney, City of Sydney Archives Function No. 30 HYPERLINK "http://tools.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/Investigator/Entity.aspx?Path=\\Function\\30" http://tools.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/Investigator/Entity.aspx?Path=\Function\30 Viewed 21 January 2011

[31] The Sydney Committee, Minutes of the Programme Committee 19 March 1976, City of Sydney Archives, CSA014504/003

[32] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1987

[33] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1980

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1981

[35] This was the case in cities across America, the United Kingdon and Australia. See David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005

[36] The Sydney Committee, Minutes of the Festival Council 10 April 1985; 18 June 1985; 3 July 1985; 12 September 1985

[37] The Sydney Committee, Minutes of the Festival Council 12 September 1985, City of Sydney Archives, CSA014504/003

[38] The Sydney Committee, Minutes of the Festival Council 17 July 1986, City of Sydney Archives, CSA014511/8

[39] The Sydney Committee, Minutes of the Festival Council 24 August 1986, City of Sydney Archives, CSA014511/8

[40] The Sydney Committee, Minutes of the Festival Council 12 June 1986, City of Sydney Archives, CSA014511/8

[41] . The Sydney Committee, Minutes of the Festival Council 12 June 1986, City of Sydney Archives, CSA014511/8

[42] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1988

[43] Stephen Hall, New South Wales Bicentennial Celebrations 1988: report to the Premier of New South Wales in Stephen Hall Correspondence Files, City of Sydney Archives CSA045094 File: Premier's Department – General Bicentennial Matters

[44] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1989

[45] Howard Fireworks, http://www.howardfireworks.com.au/, viewed 21 January 2011; Foti Fireworks, http://www.fotifireworks.com.au/news/index2008archive.html, viewed 21 January 2011; Fireworks in the Family, ABC Australian Story Transcript October 6 2008 http://www.abc.net.au/austory/content/2007/s2384295.htm, viewed 21 January 2011

[46] NYE 1999 Sydney Millennium Celebrations Concept Plan in City of Sydney Archives CSA023926; See also archived website Sydney NYE 1999,http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/48251/20050307-0000/new%20year%201999/www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/nye/1999/default.html, viewed 21 January 2011

[47] See Peter Murphy and Sophie Watson, Surface City: Sydney at the Millennium, Pluto Press, Sydney, 1997, p 165

[48] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 September 1999

[49] See New Year's Eve 2000 HYPERLINK "http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/48251/20050307-0000/New%20year%202000/www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/nye/2000/default.html" http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/48251/20050307-0000/New%20year%202000/www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/nye/2000/default.html, viewed 21 January 2011, and subsequent years archived at Pandora Australia's Web Archive, http://pandora.nla.gov.au/tep/48251, viewed 4 July 2011

.