The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Planning

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Planning

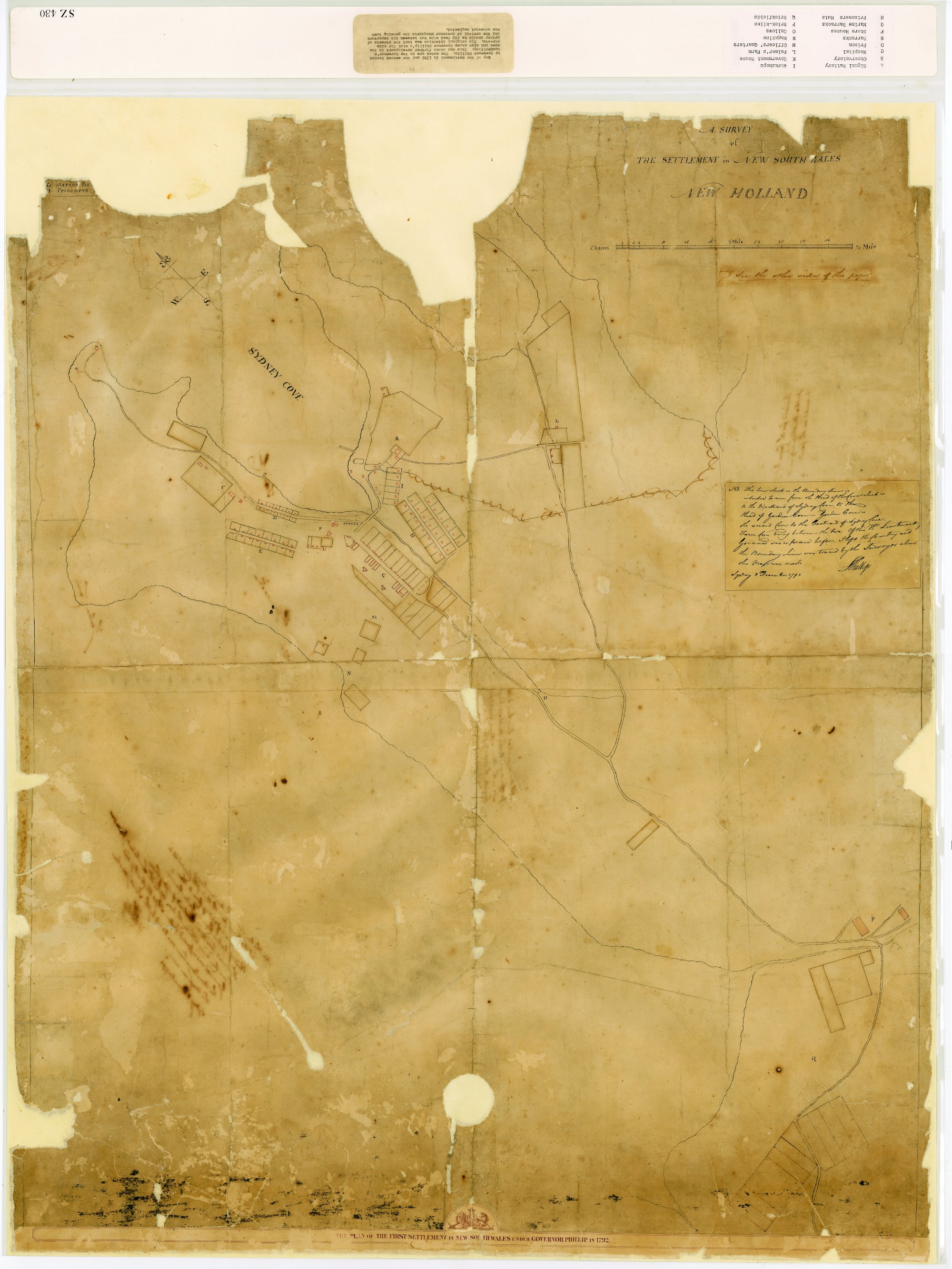

[media]Sydney has been described as an 'accidental city', one with a planning history characterised by opportunistic development and disjointed or abortive attempts at holistic planning. [1] At the first Australian Town Planning Conference and Exhibition held in Adelaide in 1917, JD Fitzgerald – politician and leading town planning advocate – lamented that Sydney was 'a city without a plan, save whatever planning was due to the errant goat. Wherever this animal made a track through the bush', he observed, 'there are the streets of today'. [2]

Sydney Town

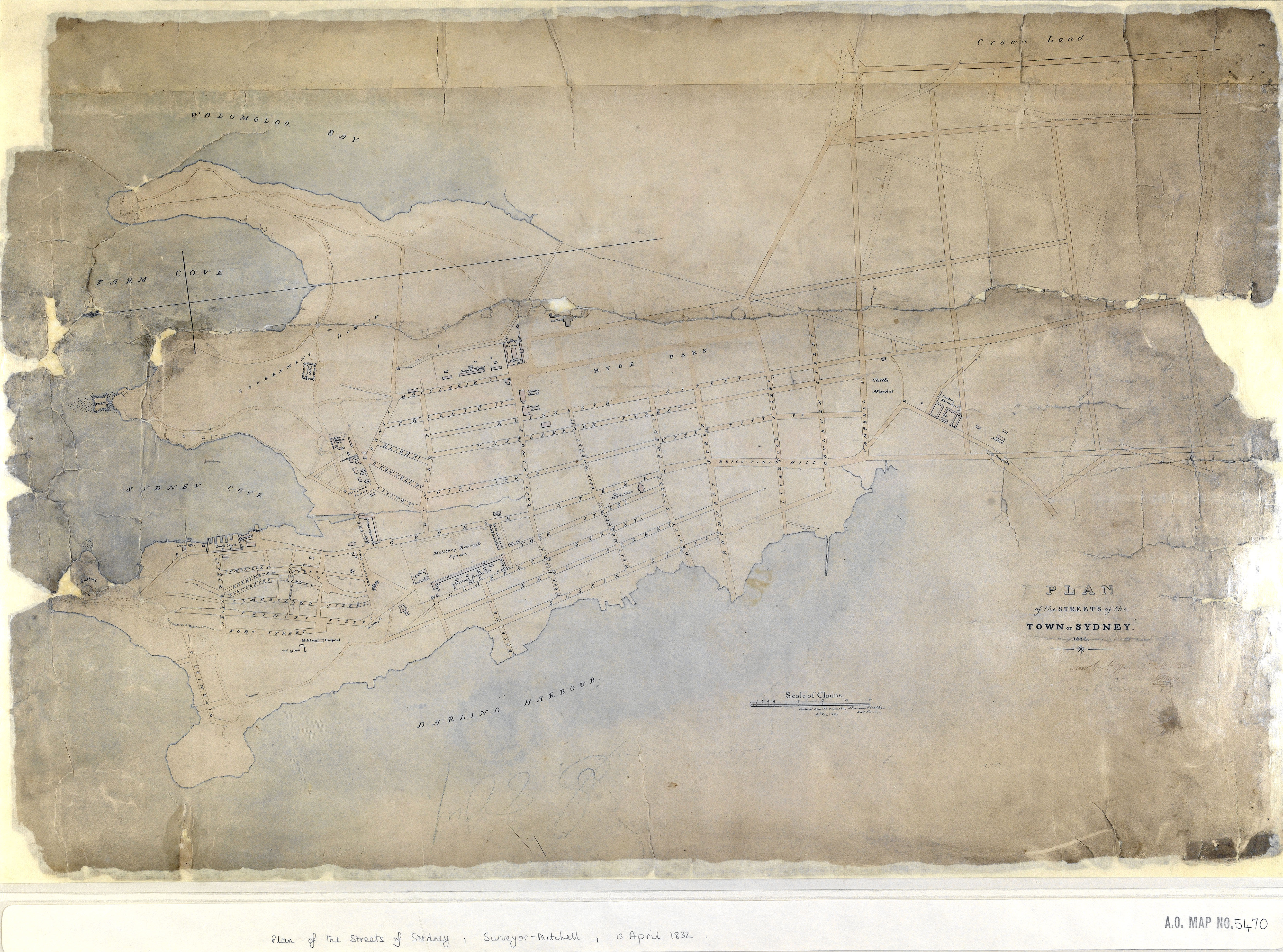

Despite attempts by colonial governors back to Arthur Phillip to regulate urban growth, early Sydney grew 'like Topsy'. In his 1832 Report on the Limits of Sydney, Surveyor General Thomas Mitchell noted that most peripheral town land had 'been alienated and that roads and boundary lines were oblique and irregular'. [3] Further chaos ensued when Mitchell attempted to 'square the lands of individuals conformably to a general plan of Streets'. [media]Mitchell's neat roads were proclaimed rights of way during 1834. Adversely affected landowners swamped the government with claims for compensation, leading subsequently to a select committee to untangle the web of claims and counterclaims. Private property interests won out, and Sydney Town was set ultimately to become the densest core of a sprawling city.

Nevertheless, the rapid economic and demographic expansion which led to the commissioning of Mitchell's Report made it necessary to implement general controls on development. Physical expansion and bursts of building activity put pressure on officials to clearly define the town's boundaries. Thus provisions for regulating some features of the built environment were incorporated into the Police Act which was passed in 1833. Other pieces of legislation were applied to Sydney in the 1830s to curb bad building and subdivision practices. These included a Streets Alignment Act (1834) and a Building Act (1837) based on the London Building Act of 1774.

Sydney becomes a city

[media]Some observers argued the need for a civic authority to regulate the built environment. But attempts to incorporate Sydney provoked heated debate among well-heeled residents and property owners. Governor Sir George Gipps finally succeeded in having a municipal bill enacted in 1842 after a two-year battle. Based on the 1835 British Municipal Corporations Act, the Sydney Corporation Act bestowed the status of City on Sydney, albeit prematurely, and ostensibly empowered the Corporation to make by-laws to control urban growth. The Act was deficient in enforcement powers and from the mid 1840s, conservative colonial political factions chipped away at the City Corporation's powers and public profile. In 1853, the City Council was sacked, for the first of what was to be a number of occasions, for supposed inefficiencies, and replaced by colonial government appointed commissioners.

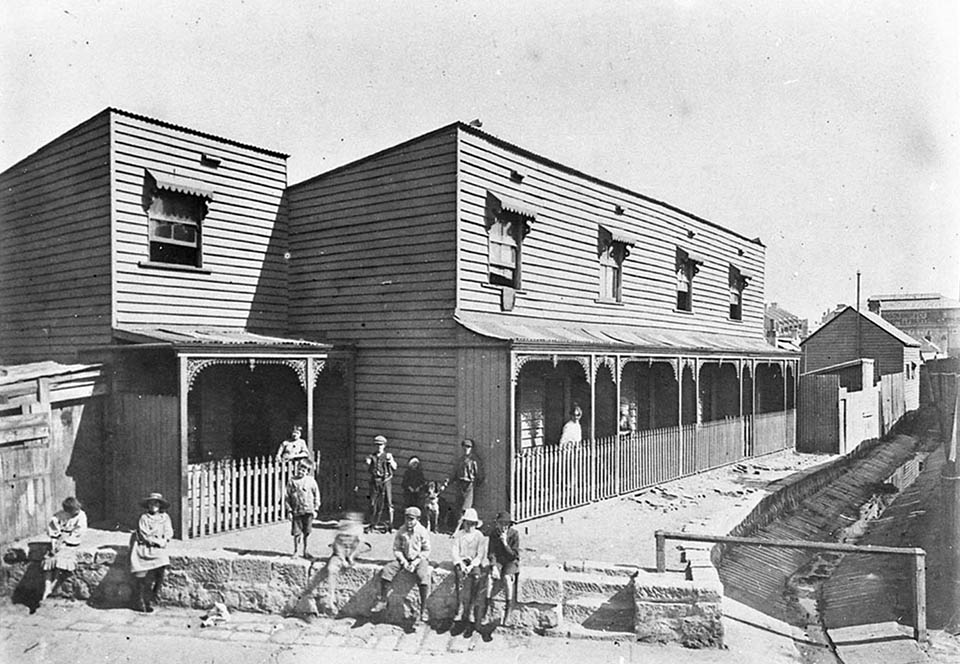

For the next 20 years or so, the City Surveyor and other Corporation officials became increasingly demoralised as their attempts to regulate development in the City were frustrated by inadequate legislative tools and an uninterested colonial administration. By the close of the 1870s, a decade of significant and complex economic growth and of increasing social problems, no one could credibly doubt 'the urgent necessity … for legislation on this subject'. [4] [media]Public health issues of sanitation, water supply, sewerage, and pollution brought concerns to the fore.

City improvement legislation

Outbreaks of deadly diseases, an accumulation of structurally dangerous or unsanitary buildings and an urban infrastructure increasingly unable to cope with the pressures of urban growth spurred the City Corporation to draft a City Improvement Bill. This was placed before the colonial legislature at the end of 1877, but the Bill was not considered by a Select Committee until February 1879 and was attacked by property owners, many of whom were slum landlords. Two months later the City of Sydney Improvement Act was given Royal Assent. The Act was a shadow of the original Improvement Bill and was almost immediately found to be defective and incomplete. Nevertheless, it was central to building control in Sydney for the next half century and spurred the demolition of scores of dilapidated and dangerous buildings.

[media]In 1880 the colonial government passed the Land for Public Purposes Acquisition Act which led to a spurt of public park formation in Sydney over the next few years. As a response to concern about the higgledy-piggledy formation of streets, the Width of Streets and Lanes Act in 1881 influenced the morphology of the inner and middle-ring suburbs until the 1920s, by requiring streets 66 feet (20.1 metres) wide and lanes 20 feet (6 metres) wide. However, a holistic conception of metropolitan planning needs was slow to develop.

In the 1890s, economic depression and social dislocation – in part the product of laissez faire policies – stimulated activity among the 'most earnest and energetic' of Sydney's citizens. Much of the city's vital infrastructure was obsolete. Representatives of capital, labour and a new style of Liberalism engaged vigorously in debate over questions of improving and rebuilding the city. At the turn of the twentieth century, new ideas from Europe and the United States were increasingly applied to urban questions as decision makers and experts tried to 'embrace the advantages accruing from the science of life as exemplified in other cities'. [5] While new innovations and regulation in the early decades of the twentieth century were based on imported ideologies emanating from an ascendant international town planning movement, much of what actually happened as a result was predicated on Sydney's political economy.

'Convenience, healthfulness and beauty'

[media]John Sulman, British expatriate, Sydney architect and the pre-eminent figure in Australian town planning from the 1900s, had foreshadowed central concerns of the movement in the early 1890s. Sulman declared that the 'typical mode of sub-division' in Australia was:

a case of individualism run mad. And with no better result than that in the course of years, and after many rebuildings, some kind of order and classification will have been evolved out of the chaos of the commencement. Whereas it should not be forgotten a modern town is an organism with distinct functions for its different members requiring separate treatment, and it is just as easy to allot these to suitable positions at first, as to allow them to be shaken with more or less difficulty into place. [6] (our emphasis)

These observations represent an early reference to land use zoning, the primary method of statutory planning control only belatedly enacted in the 1940s. [7] More importantly, his sentiments illuminate the strong influence of British social theory on the planning ideologies espoused by local planning luminaries. These early writings show the grip of social Darwinism on nascent planning thought. For Sulman, if towns and cities 'of the future [were to] far surpass those of the present in convenience, healthfulness, and beauty' [8] – if society in general and individuals in particular were to be uplifted to a higher level of being – urban disease would have to be planned away and present cankers cured by experts. Cramped and unsanitary working-class row and terrace housing in the inner suburbs was anathema to the reformer. Social Darwinist thought provided flexible arguments for the amelioration of such urban nuisances as the nastier effects of laissez-faire capitalism.

This approach was also influenced by euthenics, an environmentally deterministic pseudo-science which sought to improve living conditions to effect improvements in human beings. [9] In adopting euthenics as a tool for social engineering and urban reform, Sulman and his colleagues embraced a liberal collectivist tradition which placed at centre stage a common good or social goals based on apolitical consensus. It represented a platform for the advancement of early planning goals, just as later cross-party ideologies would underpin crucial chapters in Sydney's planning history. However, the redistributive potential of planning was destined to make it an inherently political and often controversial instrument in practice.

Plague and its consequences

Town planning in Sydney was first taken up in earnest in the early years of Federation. [media]Late in the summer of 1900, bubonic plague broke out in Sydney. During the epidemic, which lasted for over six months, 303 people were reported to have contracted the disease and one third of them died. [10] Though the plague terrified Sydney more than its severity warranted, the City Council sardonically hailed the plague as 'the greatest blessing that ever came to Sydney, viewed from the standpoint of the future welfare of our City'. The presence of plague starkly exposed the gross deficiencies in the regulation of the city's development. Fear of contagion fuelled popular demands for immediate reforms. The New South Wales government's response was to place 'the whole blame … upon the shoulders of the City Council' [11] while finally focussing its attention on restructuring the city's port infrastructure in particular. On 23 March 1900, the government took control of the waterfront areas abutting the city's commercial wharfage along Darling Harbour at Millers Point and The Rocks.

Property resumption became one of urban reform's most powerful instruments. It was wielded often and with vigour by the state and its various agencies and by the Sydney City Council, the latter via provisions in the amended Corporation Act. Council resumptions began in March 1906 and 119 compulsory resumptions had been conducted by 1917. These ranged from individual properties to large-scale clearances at a cost of over £2.3 million. [media]Slums were razed, usually to make way for new industrial and warehouse buildings.

Efficiency and progress

'Improvement' and 'beautification', inspired by the city beautiful movement, became buzz words in civic and professional circles as schemes were hatched for new artistic and aesthetic interventions like boulevards, public squares, and civic centres. [12] But underlying such surface improvements was the notion of efficiency as the cornerstone of social and material progress. [media]Parks, for example, were not only the 'lungs of the city' and a manifestation of civic pride and worth, but morally and mentally uplifting. Lord Mayor Allen Taylor informed his fellow aldermen that they must be maintained at the 'highest state of efficiency'. [13] More was at stake: planning could also contribute to 'national efficiency' which rested upon three essential elements: industrial competency, social harmony and the organisation of society. National efficiency demanded the 'most efficient adaptation of means to produce the highest welfare and civilisation of a people and to ensure its survival against internal diseases and the attacks of other nations'. [14]

To these ends a Royal Commission for the Improvement of the City of Sydney and its Suburbs was conducted between June 1908 and May 1909. [15] The aim was 'to fully inquire into the whole subject of the remodelling of Sydney'. The Final Report presented findings under four headings: traffic considerations, beautification of the city, slum areas and housing reform, and the future growth of the city. The Commissioners noted that 'the mistakes of early rulers and residents' now meant that the central city 'presents few opportunities for town planning on modern lines'.[16] Piecemeal restructuring and redevelopment based on the requirements of capital would continue to characterise the city's growth pattern, and an extensive series of mainly street improvements was recommended, many of which were carried out.

Planning the suburbs

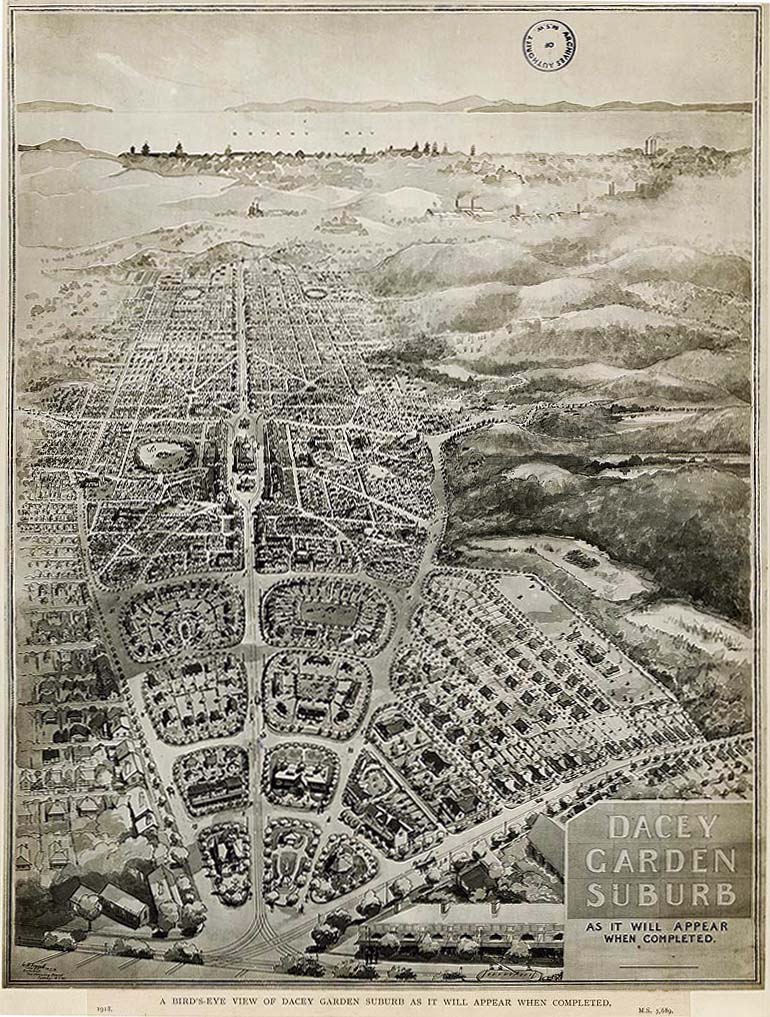

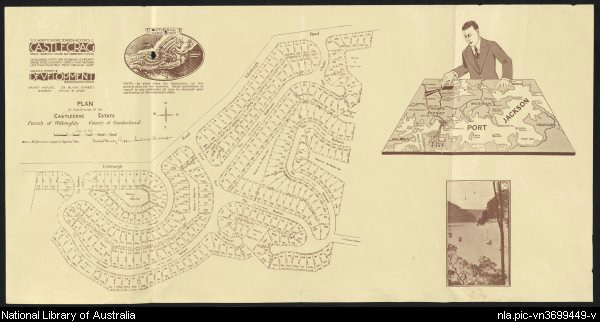

More [media]hope was held out for the influence of the emerging science of town planning in Sydney's new suburbs. Legislation along the lines of the proposed UK Housing, Town Planning Act (1909) was endorsed, but never enacted. Instead the practical side of suburban planning was captured in various model suburbs. The New South Wales Housing Board's first model workers' suburb Daceyville (1912), designed by JD Fitzgerald and John Sulman, and modified by William Foggitt, was hailed as the 'first city beautification scheme on modern lines in Australia'. Here the outmoded 'gridiron' layout was 'now condemned'. [17] The garden suburb ideal, prevalent from around 1910 until 1930, was stripped bare of any true social reformism by real estate interests who simply latched on to its picturesque appeal and geometric street patterns. [18] Rarer were flawed experiments such as a garden village for disabled war veterans at Matraville [19] and the middle class suburb of Castlecrag, where Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin tried to fashion a new bohemian politics in a suburban bushland setting.

From its formation in October 1913 by George and Florence Taylor, the Town Planning Association of New South Wales lobbied strongly for planning reforms, initially with strong support from the city's leading architects, surveyors and engineers. The outbreak of World War I hampered practical outcomes but the dialogue between state officials, civic authorities and planning advocates was revived as considerations of postwar reconstruction and repatriation loomed large towards the close [media]of hostilities. In 1917 JD Fitzgerald called for the universal adoption of town planning ideals, involving the

benevolent co-operation of statesmen of all parties … of men of good will of all churches and creeds… [and] of [all] unclassified bodies of men and women who love their country and desire its development and progress. [20]

Planning for expansion

Fitzgerald was better placed than anyone to realise these goals as Minister for both Local Government and Public Health in 1916–19. His great passion was a new system of governance for greater Sydney to include metropolitan-wide town planning controls. His campaign threatened vested interests. The Town Clerk of Sydney, Thomas Nesbit, wrote with great vitriol that Fitzgerald was:

a municipally gilded god, possessing feet of clay, when matters of practical application municipally were involved, whose iteration and reiteration of the parrot-like cry, the voice of one crying in the wilderness 'wait for the Greater Sydney Bill', ultimately developed into arrant nonsense, mere claptrap and sheer humbug. [21]

Fitzgerald's major success was a revised Local Government Act in 1919. This extended the range of discretionary powers for councils in subdivision and development matters (although not far enough according to Nesbit). While planning controls were not introduced, councils were empowered to declare 'residential districts', a provision exploited wilfully by well-heeled municipalities anxious to prevent incursions by factories and shops. Fitzgerald also appointed a Town Planning Advisory Board.[media] The pattern of metropolitan growth was left to market forces. In the 1920s a civic-professional movement called the Sydney Regional Plan Convention failed to convince the state government to take on the task of preparing a metropolitan plan for Sydney. [22]

From the end of World War I to the end of World War II, practical planning in Sydney meant the micro-operations of the Local Government Act. In the wake of the Great Depression, political priorities through most of the 1930s lay elsewhere. Sydney City Council made little progress on a coherent planning vision and did not appoint Dugald McLachlan as its first planning officer until 1938 and only then at the level of assistant. [23] There were state government inquiries into the remodelling of Circular Quay and Macquarie Street. In 1936 a Town and Regional Planning Bill was drafted but never introduced into the Parliament. In 1934 a new generation of planning advocates reassembled in a new professional body, the Town and Country Planning Institute of New South Wales.

Postwar reconstruction and change

War again brought a halt to much planning activity from 1939 but it also provided an impetus for change accepted by the political right and left in the name of postwar reconstruction. Echoes of the ideal of a Greater Sydney could be traced into two major local government reforms. One was the rationalisation of local government. In July 1944 Labor Premier William McKell announced that he intended to introduce legislation concerning 'the extension of the boundaries of the City of Sydney and the Union of Areas in the County of Cumberland'. [24] A Royal Commission on Local Government Boundaries was appointed in 1945 and, after some wheeling and dealing, an Act was passed three years later. Eight small municipalities – Alexandria, Darlington, Erskineville, Glebe, Newtown, Paddington, Redfern and Waterloo – were incorporated into the City of Sydney, which expanded to cover 11 square miles (28.5 square kilometres), in the process ensuring two decades of Labor-dominated city councils. Further changes to the boundaries of the City of Sydney would occur in 1968, 1982, 1989 and 2004.

A second and more radical innovation in metropolitan governance was the formation of the Cumberland County Council as a tier of government intermediate between local and state governments, to oversee preparation and implementation of Sydney's first statutory metropolitan plan. The Council was established under the provisions of the Local Government (Town and Country Planning) Amendment Act 1945, which enabled councils to prepare comprehensive local planning schemes for the first time. The process was overseen by a new Town Planning Branch in the Department of Local Government headed by Norman Weekes, with another new creation, the Town and Country Planning Advisory Committee, overviewing and providing high level ministerial advice.

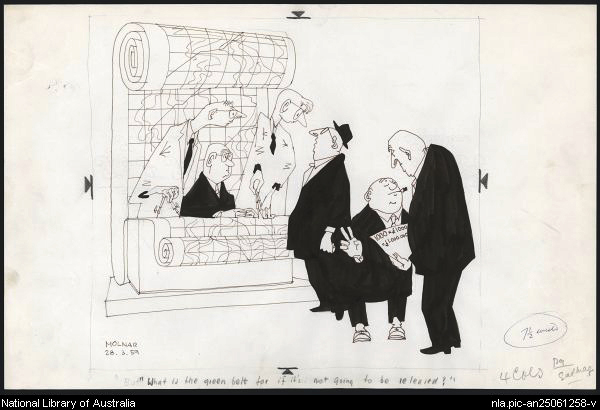

Released in 1948 but not legally gazetted until 1951, the County of Cumberland Planning Scheme was once described as 'the most definitive expression of a public policy on the form and content of an Australian metropolitan area ever attempted'. [25] With some inspiration from the famous London plans by Patrick Abercrombie, the County Scheme introduced land use zoning, suburban employment zones, open space acquisitions, and the green belt to Sydney. The Main Roads Department supplied a ready-to-go expressway network. Yet, despite the best intentions, the Cumberland County Council was an overall failure. [media]It met strenuous opposition from property owners and by the mid-1950s had 22,000 claims against it for 'injurious affectation' arising from County zoning. [26] It also faced hostility from more entrenched state government agencies such as the Sydney Water Board and the Department of Housing.[media] The green belt to prevent sprawl was the most contentious element, and land releases incrementally whittled it away to accommodate unpredicted population increases from international migration and the 'baby boom'. A breakthrough compromise was the securing of developer contributions to help fund infrastructure in new release areas. [27]

Suburban councils were slow to prepare comprehensive town planning schemes. Only four suburban municipalities had developed schemes by the time of the Cumberland County Council 's demise in 1963. The Sydney City Council put its plan on display for three months in 1952 but, incredibly, it was not legally approved by the state government until 1971, just four days before the City's first genuine and innovative strategic plan was released. [28] Interim development control orders constituted a makeshift planning system in the meantime, but change in the city became increasingly chaotic. Traffic congestion worsened: one Friday in December 1956 was dubbed 'Black Friday' after traffic ground to a halt for up to 40 minutes in some parts of the city. By then the City had already committed to the Cahill Expressway [29] and the state government was well on its way to dismantling a functional, metropolitan system of tramways.

Going up and spreading out

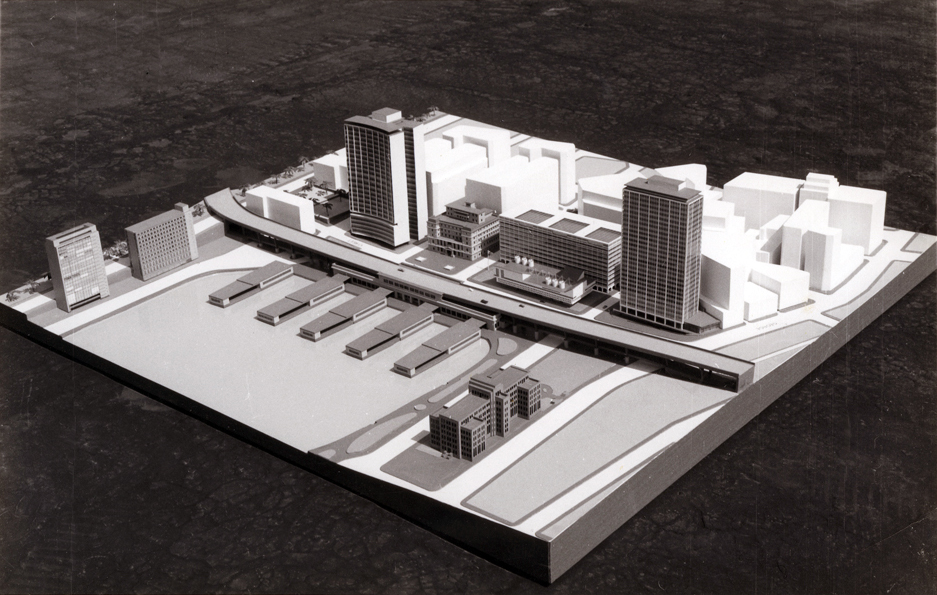

[media]A 1957 amendment to the 1912 Height of Building Act ushered in a new form of development in central Sydney. In that year, availing itself of new provisions relaxing the old 150-foot (45.7-metre) limit, the Australian Mutual Provident Society razed the nineteenth-century Farmers and Graziers Building on an island block at Circular Quay and proceeded to erect Sydney's first skyscraper. Finance capital was conspicuously supplanting pastoral capital. A building boom ensued. [media]Between 1956 and 1964, the value of new building stock in the city, most of which was commercial, soared from around £3 million to almost £51 million. [30]

From 1964 until 1974, broad responsibility for planning matters in New South Wales passed to the State Planning Authority. Unlike the Cumberland County Council, it had significant powers to acquire and develop land as well as the ability to specify corridors for development and 'growth areas'. But it was also subject to direct ministerial control. [31] In its 1968 Sydney Region Outline Plan , the State Planning Authority identified a variety of options for controlling growth. These included settling up to 60,000 people at Menai, 1.75 million people in growth corridors, and 500,000 people in the Gosford–Wyong area. [32] Given miscalculations, especially in economic trends and transport, the State Planning Authority helped create as many problems as it solved. This was symbolised in troubled social experiments at places such as Green Valley and Mount Druitt. The State Planning Authority's selection of places for growth also saw it ridiculed for providing land speculators with guides to getting rich quickly. Nevertheless, Sydney Region Outline Plan set the basic blueprint for metropolitan corridor development in evidence today. Intervention in Mt Druitt town centre and the setting up of the Macarthur Development Corporation in 1974 signposted a more proactive implementation strategy by the state government.

Renewing the inner city

In the inner city, the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority was founded in the late 1960s. This was the prototypical urban development corporation, bypassing the Local Government Act to increase the value of government-owned harbour-front land at the Rocks through redevelopment for high rise offices, hotels and apartments. Release of its 1970s scheme came at the end of the long boom, with oil crises, Vietnam moratoriums, critiques of modernism, and the rise of environmentalism, feminism and the heritage movement all challenging received wisdoms. This was the era of street protests, resident action groups and green bans imposed on controversial development projects by the Builders Labourers Federation. The upshot was a revolution in the New South Wales planning system, with replacement of the State Planning Authority by the Planning and Environment Commission, passage of the New South Wales Heritage Act (1977) and the landmark Environmental Planning and Assessme nt (EPA) Act (1979), and establishment of the Land and Environment Court (1979).

[media]During the 1980s, the City experienced another building boom and a reversal in the long-term decline of the inner city residential population. Encouraged by the state government, developers were attracted to the central and inner city as older industrial and waterfront areas fell out of commercial use and became increasingly valuable as residential property. The key state agency was the Darling Harbour Authority (1984), modelled on the London Docklands Development Corporation. Like Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority, it wrested planning control from the Sydney City Council. The Council itself was disbanded by the state government from 1986–88. On its return, it launched a new Central Sydney Strategy (1988) which placed new emphasis on urban design projects, complementing the state's other intervention into bicentennial-inflected improvements at Circular Quay and Macquarie Street.

Urban consolidation

Metropolitan Sydney in the 1980s faced a growing scarcity of land, rising land prices, and service and infrastructure shortages in far-flung suburbs. Urban consolidation, which entailed increasing housing and population densities, was taken up by the state government as a key remedy to these problems. [33] It faced opposition from some local councils wishing to retain traditional low density development. The tension continues today, with the state government holding the upper hand and being prepared to dismiss councils or strip them of planning powers if densification targets are not met. Urban consolidation was most effective from 1988 after the state government ramped up its policies and mechanisms for promoting multi-unit dwellings. In that year, the Department of Environment and Planning (established 1980) published a new regional plan entitled Sydney into its Third Century: Metropolitan Strategy for the Sydney Region.

The 'Greater Metropolitan Region'

From the mid 1990s the state government increasingly directed the urban governance of Sydney. Another new metropolitan plan appeared in 1995, Cities for the 21st Century, stressing four major goals of equity, efficiency, environmental quality and liveability, as well as introducing the concept of a 'Greater Metropolitan Region' stretching from Newcastle to Wollongong. The plan was released alongside a new integrated transport strategy. Testimony to the dynamism of the era, another new plan followed just three years later, Shaping Our Cities (1998), along with a companion report, Shaping Western Sydney (1999). The 1998 metropolitan strategy was a generalised plea for a more compact metropolis with familiar themes of better integration of land use and transport and promotion of suburban activity centres, but with a more explicit concern with urban design at a regional scale. [34] The 1990s was the decade in which intergenerational equity, resource conservation and sustainability emerged as major planning themes at all levels in the wake of the internationally influential Brundtland Commission's Our Common Future (1987).

Public–private partnerships

The 1990s also marked the forging of a neo-liberal political consensus, involving a move away from large-scale state expenditure and control in the social welfare tradition toward privatisation and deregulation, with the state more active as a facilitator of change. The most visible sign was public–private partnerships for the funding of planned new infrastructure, notably railways (the Airport Line) and expressways, resuscitated after earlier building programs were stalled by community protests and fiscal crisis in the 1970s. The Sydney Harbour Tunnel (1992) set the mould and new expressways, mostly tolled, were progressively assembled into a metropolitan ring road called the Sydney Orbital by 2007.

Global city

In the 1990s, planning in the central city and strategic suburban locations also became hitched to the production of a globally competitive city. [35] Sydney became a metropolis of projects, largely driven by private capital and with central authorities guiding significant development through mechanisms that removed development consent from local councils. These included development corporations and special legislation suspending provisions of the Environmental Planning and Assessment (EPA) Act. The major hot spots included the redevelopment of Pyrmont and Ultimo for high density and mixed use and the development of Fox Studios complex at Moore Park, both results of rising recognition of the cultural economy of cities. [36] There was some rationalisation of the various state corporations operating in central Sydney with formation of the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority in 1998. [media]The climax of the decade was redevelopment of Homebush Bay for the staging of the 2000 Olympic Games – the ultimate prize for aspiring global cities.

Through the 1990s, the state government also institutionalised its stake in major CBD development through the Central Sydney Planning Committee (1989), undertaking intensive involvement in detailed design matters. Under new independent Mayor Frank Sartor, the City itself carved out a fresh planning agenda in the Living City strategy (1994), a vision of a vibrant 24-hour pedestrian-friendly city with a permanent residential population, leisure and arts opportunities, and a quality public realm. This rolled out into an ongoing series of design projects, some in partnership with the New South Wales Government Architect. 'Design excellence' for new buildings was promoted through statutory requirements for detailed briefs and consideration of alternative schemes in a new design competition process. This represented a major step in a long evolution from 'design agnosticism' to 'design commitment' in Sydney's CBD. [37]

The end of sprawl

The first decade of the twenty-first century was marked by yet another metropolitan plan, City of Cities (released December 2005). This established a series of targets for environmental quality, employment level and location, transport, regional open space, and housing density and affordability. The plan reflects themes in the latest crop of metropolitan strategies nationwide: compact city, sub-regional activity centres, transport-land use integration, importance of infrastructure, urban design, concern about car dependence, and all-of-government implementation. [38] The twist was a remarkably detailed and robust vision of a multicentred and corridored metropolis. [39]

Suburban development remains driven by urban consolidation objectives, and the City of Cities plan proposes that up to 70 per cent of new housing by 2031 should be in established areas. Despite dissenters pointing to lack of either research evidence or examination of alternate urban forms, [40] urban consolidation remains entrenched. A policy initially introduced to optimise existing infrastructure for cost reasons has attracted other objectives of improved public transport patronage and urban design. What began with an enabling of dual occupancy has developed into a multifaceted program targeting rezoning of surplus government land, higher dwelling density targets for new release areas, and multiple-dwelling targets in areas rezoned by local councils. Master-planned communities stressing different themes of lifestyle, security and prestige have become a major feature of the residential property market in both the inner and outer city. [41]

Despite media interest in outsized suburban 'McMansions', suburban sprawl in the old-fashioned sense is outlawed. The state government's Metropolitan Development Program, with its origins in the implementation of Sydney Region Outline Plan, provides the framework for managing housing supply and infrastructure provision. Since 2004, greenfield urban development has been coordinated by a new Growth Centres Commission (2004) and focused on two new urban sectors to the northwest and southwest. The recent focus of urban renewal has been the Green Square project, largely within the old working-class suburb of Zetland. This is slowly but steadily being transformed into a higher density housing precinct with over 30,000 residents and nearly as many jobs. The City Council has taken the lead role, in association with the Department of Planning and Landcom. Adjacent, but closer to the CBD, the Redfern–Waterloo Authority (2004) is similarly targeting residential revitalisation and employment around several strategic sites.

Sydney's future

From an accidental 'city without a plan', Sydney has become a city with many plans. Some would say too many, and there have been endless rounds of planning system reform since the 1980s. Within the welter of state, regional and local planning instruments, and despite the participatory rhetoric of the planning system, the state government maintains the last word. Major amendments to the EPA Act in late 2005 provide for development approvals by the Minister for Planning for major projects encouraging economic growth. This sort of centralisation is welcomed by the property and development sectors which are in favour of further streamlining approval. [media]Ironically the Minister for Planning when these new laws were introduced was Frank Sartor, an outspoken advocate for local government powers and discretion in planning matters when he was Lord Mayor of Sydney.

[media]The central city and suburbs no longer grow 'like Topsy' but with the greater metropolitan area still being propelled by market forces towards a population of seven million by the mid twenty-first century, there are new sets of pressures around old problems (development versus environment, local–state tensions, congestion) and new ones (affordability, social polarisation, impacts of climate change). These inescapably challenge Sydney, as the first Australian city and the one most connected to the global economy.

Notes

[1] Paul Ashton, The Accidental City: Planning Sydney Since 1788, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney 1993, p 12

[2] JD Fitzgerald, 'The President's Address', Australian Town Planning Conference and Exhibition, Official Volume of Proceedings, Vardon and Sons, Adelaide, 1918, p 35

[3] Christopher Keating, Surry Hills: The City's Backyard, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney 1991, p 18

[4] Report from the Select Committee on the City of Sydney Improvement Bill…, Government Printer, Sydney, March 1879, in Journal of the Legislative Council, 1878–9, vol xxiv pt 11, p 179

[5] City of Sydney, Town Clerk's Report, 1898, p 2

[6] John Sulman, 'The Laying Out of Towns', Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science, Report of the Second Meeting, Melbourne, 1890, pp 731–2

[7] Robert Freestone, 'John Sulman and “The Laying Out of Towns”', Planning History Bulletin, no 5, vol 1, 1983, p 20

[8] John Sulman, 'The Laying Out of Towns', Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science, Report of the Second Meeting, Melbourne, 1890, p 735

[9] EH Richards, Euthenics, Whitcomb and Barrows, Boston, 1910

[10] Peter Curson and Kevin McCracken, Plague Sydney: The Anatomy of an Epidemic, UNSW Press, Sydney, 1998

[11] City of Sydney, Town Clerk's Report, 1900, p 3

[12] Robert Freestone, Designing Australia's Cities: Commerce, Culture and the City Beautiful 1900–30, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2007

[13] Sydney City Council, Proceedings of Council, 1906, pp 348

[14] RF Irvine, 'Town Planning and National Efficiency', in RF Irvine et al, National Efficiency: A Series of Lectures, Victorian Railways Printing Branch, Melbourne, 1915, p 6

[15] Robert Freestone, 'Royal Commissions, planning reform and Sydney improvement 1908–1909', Planning Perspectives, 21, pp 213–231

[16] New South Wales Parliamentary Papers, Sydney, 1909, pp vii–lxi, xxix, 17–259

[17] Sydney Morning Herald, 21 March 1912, p 7

[18] See, for example, Robert Freestone, 'The Great Social Lever of Reform: The Garden Suburb 1900–30', in Max Kelly (ed), Sydney: City of Suburbs, University of New South Wales Press in association with the Sydney History Group, Kensington, 1987, pp 53–76

[19] Paul Ashton, 'Repatriation Homes: Matraville Garden Village for Disabled Soldiers and War Widows', Journal of Australian Studies, 60, 1999, pp 73–83

[20] JD Fitzgerald, 'The President's Address', Australian Town Planning Conference and Exhibition, Official Volume of Proceedings, Vardon and Sons, Adelaide, 1918, p 35

[21] Town Clerk, Annual Report, Sydney City Council, 1920, pp 163–64

[22] Robert Freestone, 'The Sydney Regional Plan Convention: An experiment in metropolitan planning 1921–1924', Australian Journal of Politics and History, 34, 1988, pp 345–358

[23] Paul Ashton, The Accidental City: Planning Sydney Since 1788, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney 1993, p 61

[24] JDB Miller, 'Greater Sydney, 1892–1952', Public Administration, 13, 1954, pp 118–9

[25] Peter Harrison, 'Planning the Metropolis', in RS Parker and PN Troy, The Politics of Urban Growth ANU Press, Canberra, 1972, p 68

[26] Murray Wilcox, The Law of Land Development in New South Wales, The Law Book Company, Sydney, 1967, p 192

[27] John Toon and Jonathan Falk, Sydney: Planning or Politics. Town Planning for Sydney Region since 1945, Planning Research Centre, University of Sydney, 2003

[28] John Punter, 'Urban Design in Central Sydney 1945–2002: Laissez faire and Discretionary Traditions in the Accidental City', Progress in Planning, 63, 2005, p 49

[29] Paul Ashton, '“An Architectural Monstrosity”?: The Cahill Expressway and Town Planning', in Martin Crotty and David Andrew Roberts (eds), The Great Mistakes of Australian History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2006, p 99

[30] Ray W Archer, 'Market Factors in the Development of the Central Business District Area of Sydney' in Patrick Troy (ed), Urban Redevelopment in Australia, ANU Press, Canberra, 1967, p 274

[31] Peter Spearritt and Christina DeMarco, Planning Sydney's Future, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1988, pp 26–32

[32] State Planning Authority, Sydney Region Outline Plan 1970–2000, Sydney, 1968

[33] Mark Peel, 'The Urban Debate: From “Los Angeles” to the Urban Village', in Patrick Troy (ed), Australian Cities: Issues, Strategies and Policies for Urban Australia in the 1990s, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1995, pp 45–7

[34] Robert Freestone, 'Planning Sydney: Historical Trajectories and Contemporary Debates', in J Connell (ed), Sydney: The Emergence of a Global City, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2000, pp 119–143

[35] Glen Searle, Sydney as a Global City, NSW Department of Urban Affairs and Planning, Sydney, 1996

[36] Robert Freestone, Bill Randolph and Carolyn Butler-Bowdon (eds), Talking Sydney: Population, community and culture in contemporary Sydney, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2006

[37] John Punter, 'Urban Design in Central Sydney 1945–2002: Laissez faire and Discretionary Traditions in the Accidental City', Progress in Planning, 63, 2005, p 141

[38] Clive Forster, 'The challenge of change: Australian cities and urban planning in the new millennium', Geographical Research, 44, 2006, pp174–183

[39] Glen Searle, 'Is the City of Cities Metropolitan Strategy the Answer for Sydney?', Urban Policy and Research, 24, 2006, pp 553–566

[40] Patrick Troy, The Perils of Urban Consolidation, Federation Press, Sydney, 1996

[41] Pauline McGuirk and Robyn Dowling, 'Understanding master-planned estates in Australian cities: a framework for research', Urban Policy and Research, 25, 2007, pp 21–8

.