The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Red Cross in Sydney in World War One

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Red Cross in Sydney during World War One

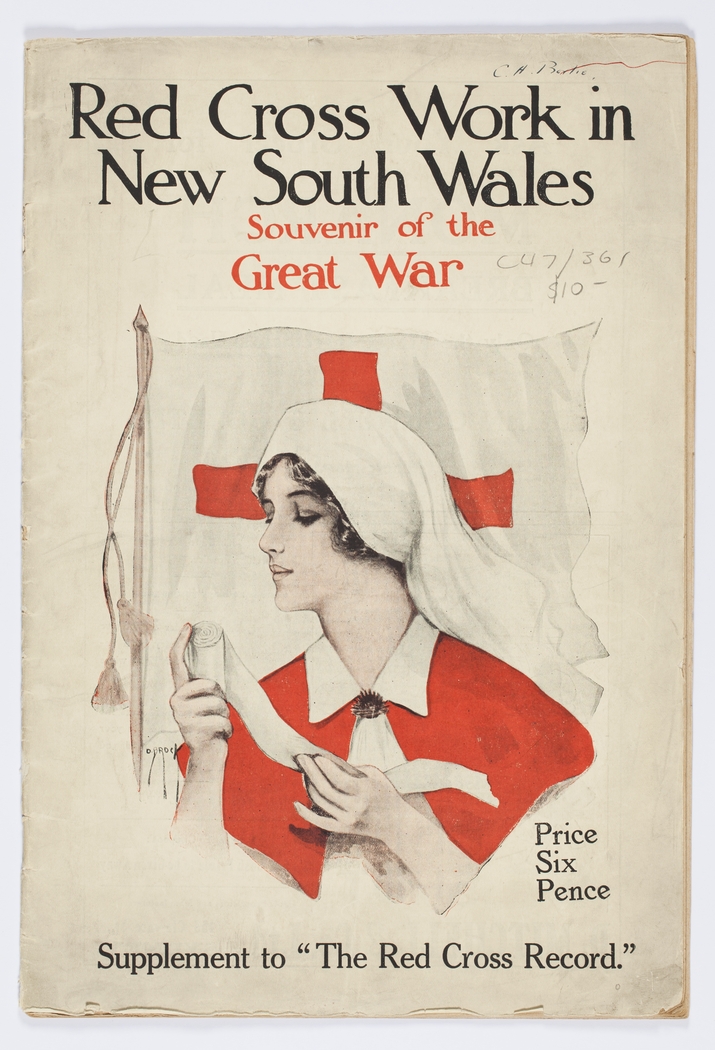

[media]At the end of August 1914 the Sydney newspaper the Sunday Times described the Red Cross as 'Angels of Mercy', 'the one bright spot' in the newly emerging war. [1] From the beginning of the Great War, Sydney women, mostly conservative, founded and joined Red Cross branches and sewed, knitted and raised funds for the war effort. They also worked in Voluntary Aid Detachments both locally and overseas. By 1918 the Red Cross effectively owned the story of the war effort at home.

Early efforts

The Women's Liberal League initiated a branch of the Red Cross League in Sydney in 1911 and in May was addressed by Australian Army Nursing Service reservist Matron EJ 'Nellie' Gould at the Queen Victoria Club, on the subject of 'How Women can Prepare to Help the Defenders of their Country, apart from Military Service'. Gould spoke again at St James Hall in Phillip Street in August. In 1913 a branch of the British Red Cross was formed at a meeting at the British Medical Association in Macquarie Street and training classes in first aid for Voluntary Aids (VAs) were organised in private homes in the eastern suburbs in July 1914. [2]

Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) had been formalised within the British Red Cross in 1909 at the request of the British Secretary of State for War. [3] VADs were part of the British Red Cross and members served as stretcher-bearers, attendants, and nurses. VADs can be traced back to the 1880s when the National Society for Aid to the Sick and Wounded in War, later the British Red Cross, trained nurses for service in Egypt and, later, the Boer War. [4] Pre-requisites included first aid and home nursing certificates. [5]

[media]The arrival in Australia of Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, wife of the governor general, in May 1914 was a turning point. Lady Helen had extensive experience with the Scottish Red Cross and at an ambulance class at St Mark's Anglican Church at Darling Point in July 1914 explained the role of the Red Cross in 'the scientific caring for wounded after battle and for those who fall sick of any of the dreadful illnesses which war invariably brings with it'. She supported national ambulance training, via St John Ambulance, and stressed that modern war had a place for 'woman in her capacity as the good-old fashioned "ministering angel"'. As she said, the British War Office appreciated the 'real national utility' of women in the Red Cross as the 'second line of defence'. [6]

On 4 August Britain declared war on Germany and Australia was also at war. Two days later Lady Edeline Strickland, the wife the Governor of New South Wales, wrote to Sydney newspapers calling for an efficient national approach to avoid duplication of effort. The general committee of the Red Cross met on 11 August in Sydney and elected an executive committee to commence work at a divisional level across the state. [7]

The formation of the Australian Red Cross

Within a week of the declaration of war Lady Helen had launched a national appeal and proposed the establishment of an Australian branch of the British Red Cross Society, headquartered in her home, Government House, in Melbourne. She planned a national council and state divisions, led by the governor's wives, and suggested the wives of mayors form local committees to cooperate with St John Ambulance and form units to make hospital comforts and clothing and raise funds. She proposed VADs be formed and assigned to the Australian Army Medical Corps for service in Australia. [8] Lady Edeline Strickland wrote to Lady Helen offering full support. [9] In Melbourne on 13 August 1914, Lady Helen presided over the founding meeting of the central council of the Red Cross at Government House. Mrs Mary Cook, wife of Joseph Cook, the Member for Parramatta and Prime Minister, attended as the sole representative from New South Wales. [10]

Red Cross branches and patriotic sewing

Women took to the Red Cross with gusto and by 12 August 1914 branches had been established by the Women's Liberal League, the Sydney Lyceum Club, and at Westmead, Bondi, North Sydney and Fairfield. [11] At Kellyville 40 women met to set up a branch and collected £8. [12] Once local Red Cross committees were formed women set about organising sewing and knitting groups, usually presided over by the mayoress, as was the case at Granville, Burwood, Smithfield and Camden. [13]

Mrs Joseph Cook and the Parramatta Branch

At Parramatta, Mary Cook took up the cause of Red Cross sewing, initially under the banner of the Parramatta Patriotic Fund. In February 1915 the Parramatta Red Cross was founded and Mrs Cook was the first president. [14] Her daughter Mary Moxham, wife of the state member for Parramatta, and the Parramatta Mayoress Mrs Graham, assisted Mrs Cook. Their sewing circle was based at Jubilee Hall. [15]

Mrs Cook's 'small army of ladies' had 11 sewing machines, donated by the Singer Sewing Company, Murray Brothers' department store and private individuals. Ladies cut fabric while others sewed and within days they had sent away 107 mosquito nets. By the end of the month the women had sent 100 pairs of knitted socks, 67 pairs of pyjamas, cholera belts, bandages and supplies such as soldiers' kits to Red Cross headquarters. [16] Their efforts were supported by girls at the Parramatta High School, Parramatta Convent and other local schools. [17]

The Argus described the atmosphere in the Parramatta Jubilee Hall:

The scene when the local ladies had their work in full swing was sufficient to fill the hearts of the most callous with grateful thoughts if also their eyes with tears. For the [items]…were being got together for the benefit of our soldier lads, some of whom may, probably will give their lives for home and king and motherland before all is over. The scene was homely enough yet most beautiful indeed in its deep-rooted lessons. There toiled the Prime Minister's wife and Mrs Moxham and the Mayoress, side by side with other busy housewives, and the daughters of the latter; and rapidly grew the piles of goods soon to be welcomed by the troops of our land. [18]

By 1917 the Parramatta Red Cross sewing circle had more than 50 members, producing 3100 items. Three spinning machines whirled constantly. The Jubilee Hall scene was repeated all over the Sydney area in quasi-industrial productions lines of sewing, while knitting, a more personal activity, was more commonly organised in women's domestic spaces at home. Wool prices forced women to spin their own yarn and by late 1917 the Red Cross Spinning Depot in George Street Sydney was teaching women to spin and several hundred spinning wheels had been sold to branches across the state. [19]

Red Cross sewing as mothering

Red Cross sewing was a practical activity that fitted the conservative values of Sydney women. Sewing circles were, as historian Emma Grahame has written, 'semi-public/semi-domestic spaces' that encouraged the agency of traditional women as cultural producers yet preserved their commitment to family and practical 'intuitive working methods'. [20] Red Cross work typified what historian Hilary M Carey has termed 'female collectivism', or collective action as a force for change. [21]

The landscape of domestic bliss and wartime voluntarism at the Jubilee Hall accorded with Red Cross values, which British historian Henrietta Donner has called an expression of love between volunteers and soldiers. [22] Historian Bruce Scates has pointed out that unpaid war work, and the emotional energy invested by women, cut across social groups. [23] It represented the idealism of a new nation, its progressive social policies and advanced democratic principles.

Sewing meetings were a direct extension of the private sphere – a form of place-based patriotism or patriotic housekeeping, where like-minded women could openly exchange views in a secure environment, away from men. Red Cross workers supported 'their boys' in their role as caring motherly figures, while the Red Cross movement used the metaphor of a mothering angel to garner support for the cause. AE Foringer's 1918 image of 'The Greatest Mother in the World', according to Canadian historian Sarah Glassford, used 'two potent images of Christian iconography: The Virgin and the Child'. The imagery expressed the 'care work of sick and wounded citizen-soldiers in terms of mothering…[and] bestowed that work with symbolic and moral power'. [24]

Fundraising

[media]Although Red Cross sewing was conducted in the private sphere, the work of raising funds to support it needed to be carried out in public. Sydney's Lady Mayoress, Mrs RW Richards, launched one of the earliest Red Cross appeals on 14 August 1914, for hospital comforts and clothing. Within a few days over £540 had been collected and by 25 August ten times that amount had been subscribed. [25] One of the most prominent supporters was the opera diva Nellie Melba who toured Australia in September 1914 for the Red Cross. Her concert at Sydney Town Hall raised £1890. [26]

[media]Branches held concerts, bazaars, fetes, stalls, raffles, sports days, card nights, garden parties, and other large community events. Subscription lists were printed in the local and city-based press and branches raised hundreds of pounds – Vaucluse had raised £1900 by 1916. [27] Local patriotic funds also donated significant funds to Red Cross causes, as was the case at Camden, where the patriotic fund contributed £426 of the £1756 raised by the local Red Cross in June 1915. [28]

Military and field hospitals

The Red Cross also set up local military and field hospitals and by 1916 the New South Wales Red Cross had responsibility for seven military hospitals and 22 field and camp hospitals. In mid-1915 the Parramatta Red Cross was asked to take charge of A Ward of the Liverpool Field Hospital, which had 14 beds. The branch fitted out the ward with dressers, safes, bedpans, plates, mugs, garbage bin, brooms, dustpan and other items, at a cost of £13. Female branch members undertook weekly visits while the branch appealed for donations of sheets and soap and raised funds at events such as Empire Day in Parramatta Park, where £620 was collected. [29] The men's branch of the Parramatta Red Cross supplied lockers, footstools, chairs, bed rests, tables and trays. [30]

The tiny Menangle Red Cross branch was responsible for supporting the field hospital at the Australian Light Horse Camp at the Menangle Park Racecourse. The branch supplied a hospital tent, fitted it out with beds, medical supplies and hospital comforts, and sewed shirts, pyjamas, socks, towels, pillow-slips and handkerchiefs while the men supplied furniture, crutches, bed rests and hot water tins. [31]

Christmas parcels

Red Cross branches in the Sydney area sent Christmas parcels to troops, paying for them from branch funds. In 1916 Parramatta Red Cross sent 25, while Red Cross branches at Camden, Narellan, The Oaks, Burragorang and Cox's River sent parcels that included including every thing from shirts to towels, wallets, caps, socks, handkerchiefs, pencils, stationery, playing cards, mouth organs, sweets, tobacco, pipes, cigarettes, puddings, tins of coffee and milk. Newspapers published soldier's thank you letters sent to branches. The Camden News printed a letter of thanks from JM Hawkey of Camden, who said his parcel 'brought back many happy recollections of dear old Camden':

I am quite sure if you good people at home could only see the joy that your parcels bring to our boys in the front line it would recompense you tenfold for your trouble. [32]

Voluntary Aid Detachments

[media]The New South Wales VA Detachments were formally launched by Colonel RE Roth, physician and lieutenant colonel in command of the 5th Field Ambulance, at Sydney Town Hall in February 1915. During the First World War there were around seventy VA detachments in New South Wales with a membership that peaked at around 3,500. In mid-1916 a group of 30 trained VAs were requested by the British Red Cross, and they served in Great Britain and France as orderlies. [33] The duties of VAs varied from working on canteens and buffets to changing beds, cleaning, sterilising equipment and record keeping.

The Parramatta VAD, the second established in New South Wales, was set up in May 1915 with 60 members, all young women from the Parramatta area who had passed first aid and home nursing examinations. Matron Simms from Parramatta District Hospital lectured them in first aid, home nursing, cooking for invalids, hygiene, and massage. Drill was an important part of the discipline within the VAD and the Parramatta VAs had drill every Monday night at the Parramatta Town Hall. [34] VAs supplied the Liverpool Field Hospital with comforts and assisted at Rose Hall Convalescent Home at Darlinghurst, Graythwaite at North Sydney and The Mill at Moss Vale. [35]

End of the war

At the end of the war cracks in the ranks began to appear. The powerful position the Parramatta Red Cross branch held created jealousies and resentment. In August 1918 The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate reported the mayor was threatening to evict the Red Cross sewing circle from Jubilee Hall as, contrary to Lady Helen's original appeal, his wife was not the ex-officio president of the Red Cross branch:

OUT! OUT!

Mayor Hill Scourges the Red Cross from the Temple

Will Parramatta Stand for it? Patriotism; or Piffle?

That Mayoral Minute.

A Flutter in Parramatta Dove-Cotes

Is the Red Cross Pilloried? [36]

The mayor backed down and the ladies remained at Jubilee Hall, earning thanks from a new mayor, and Mary (now Lady) Cook, in 1919. [37] While the Parramatta Red Cross spinning effort had closed down, as it did in many localities, sewing continued. [38] Parramatta and elsewhere shifted their focus to soldier repatriation and rehabilitation.

[media]In spite of encouragement from Red Cross leadership at a divisional and national level Red Cross membership across New South Wales crashed and community support evaporated. Branches across the state dropped from 440 in 1918 to 81 by 1921. Surviving branches were kept busy with the Spanish Influenza outbreak of 1919, while the Red Cross movement broadened its activities from the welfare of soldiers to providing convalescent services for victims of tuberculosis and the care of children.

The Australian Red Cross on the world stage

Despite the cessation of hostilities, Lady Cook remained active in the Red Cross. In 1918, while in London with her husband, who had become High Commissioner, she undertook Red Cross work with Mary Hughes, wife of Prime Minister William Morris Hughes. [39] In 1919 she became senior vice-president of the New South Wales Division and in 1923 represented the Australian Red Cross at a meeting of the International Red Cross Board of Governors in Paris and the 11th International Red Cross Conference in Geneva. [40] In 1925 she was appointed DBE for her services to the Red Cross. [41] After the Cooks returned to live in Sydney she became vice-president of the local division again and remained a member until her death in 1950. [42]

References

Carey, Hilary M. '"Doing Their Bit": Female Collectivism and Traditional Women in Post-Suffrage New South Wales'. Journal of Interdisciplinary Gender Studies, 1, No 2 (1996).

Donner, Henrietta. 'Under the Cross – Why V.A.D.s Performed the Filthiest Task in the Dirtiest War: Red Cross Women Volunteers, 1914–1918'. Journal of Social History, Spring (1997).

Oliver, Beryl. The British Red Cross in Action. London: Faber & Faber, 1966.

Glassford, Sarah. '"The Greatest Mother in the World": Carework and the Discourse of Mothering in the Canadian Red Cross Society during the First World War'. Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering. 10 (2008).

Grahame, Emma. "Making Something for Myself": Women, Quilts, Culture and Feminism. PhD. University of Technology Sydney, 1998.

Oppenheimer, Melanie. Red Cross VAs: A History of the VAD Movement in New South Wales. Walcha: Ohio Productions, 1999.

Oppenheimer, Melanie. The Power of Humanity: 100 Years of the Australian Red Cross. Sydney: HarperCollins Australia, 2014.

Scates, Bruce. 'The Unknown Sock Knitter: Voluntary Work, Emotional Labour, Bereavement and the Great War'. Labour History. No. 81 (November 2001).

Willis, Ian. Ministering Angels: The Camden District Red Cross, 1914–1945. Camden: Camden Historical Society, 2014.

Notes

[1] Sunday Times, 30 August 1914

[2] The Red Cross Record, 2 July 1917: 15; British Red Cross Society, Australian Branch (NSW Division), First Annual Report 1913–1914: 4-5

[3] Beryl Oliver, The British Red Cross in Action (London: Faber & Faber, 1966): 206

[4] Melanie Oppenheimer, Red Cross VAs: A History of the VAD Movement in New South Wales (Walcha: Ohio Productions, 1999): 4

[5] The Red Cross Record, 2 July 1917: 19

[6] Sydney Morning Herald, 29 July 1914

[7] British Red Cross Society, Australian Branch (NSW Division), First Annual Report 1913–1914: 5

[8] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 August 1914

[9] Sydney Morning Herald, 11 August 1914

[10] British Red Cross Society, Australian Branch, Central Council, Minutes, 13 August 1914. Personal communication with Moira Drew, Archivist, Australian Red Cross, North Melbourne, 14 April 2016.

[11] Bendigo Advertiser, 11 August 1914; Ballarat Star, 12 August 1914; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 12 August 1914, 15 August 1914; Sydney Morning Herald, 12 August 1914

[12] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 15 August 1914

[13] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 19 August 1914, 21 August 1914, 22 August 1914; The Camden News, 13 August 1914

[14] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 13 February 1915

[15] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 19 August 1914

[16] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 19 August 1914, 22 August 1914, 29 August 1914

[17] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 22 August 1914

[18] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 22 August 1914

[19] Sunday Times, 11 February 1917; Sydney Mail, 24 October 1917

[20] Emma Grahame, 'Making Something for Myself': Women, Quilts, Culture and Feminism' (PhD, University of Technology Sydney, 1998): 6–9

[21] Hilary M Carey, '"Doing Their Bit": Female Collectivism and Traditional Women in Post-Suffrage New South Wales'. Journal of Interdisciplinary Gender Studies, 1, no 2 (1996): 108

[22] Henrietta Donner, 'Under the Cross – Why V.A.D.s Performed the Filthiest Task in the Dirtiest War: Red Cross Women Volunteers, 1914–1918', Journal of Social History, Spring (1997): 688–689.

[23] Bruce Scates, 'The Unknown Sock Knitter: Voluntary Work, Emotional Labour, Bereavement and the Great War'. Labour History, 81 (November 2001): 35–37

[24] Sarah Glassford, '"The Greatest Mother in the World": Carework and the Discourse of Mothering in the Canadian Red Cross Society during the First World War', Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, 10 (2008): 220

[25] Sydney Morning Herald, 14 August 1914, 18 August 1914, 25 August 1914

[26] Sydney Morning Herald, 28 September 1914

[27] British Red Cross Society, Australian Branch (NSW), Annual Report 1914–1916: 59

[28] Ian Willis, Ministering Angels: The Camden District Red Cross, 1914–1945 (Camden: Camden Historical Society, 2014): 37

[29] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 20 October 1915

[30] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 14 October 1916

[31] Ian Willis, Ministering Angels: The Camden District Red Cross, 1914–1945 (Camden: Camden Historical Society, 2014): 41–42

[32] Camden News quoted in Ian Willis, Ministering Angels: The Camden District Red Cross, 1914–1945 (Camden: Camden Historical Society, 2014): 50.

[33] Melanie Oppenheimer, Red Cross VAs: A History of the VAD Movement in New South Wales (Walcha: Ohio Productions, 1999): 8, 40-42

[34] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 27 November 1915

[35] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 22 May 1918

[36] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 17 August 1918

[37] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 12 July 1919

[38] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 16 July 1919

[39] Mary Hughes, William Morris Hughes, Australia's Prime Ministers, National Archives of Australia, http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/hughes/spouse.aspx, viewed 8 April 2016

[40] Lady Mary Cook, 1923 Appointment Book, Personal Papers of Prime Minister Cook, NAA: M3580, 12; 'Mary Cook', Joseph Cook, Australia's Prime Ministers, http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/cook/spouse.aspx, viewed 25 April 2016

[41] Dame Mary Cook, 1926 Appointment Book, Personal Papers of Prime Minister Cook, NAA: M3580, 16

[42] Sydney Morning Herald, 25 September 1950

.