The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Ocean baths

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Ocean baths

Sydney [media]abounds in venues for what Kate Rew, founder of Britain's Outdoor Swimming Society, describes as 'wild swimming', [1] meaning swimming in any environment less subject to human control than an indoor public pool. The lively saltwater, and an openness to the sea, beach and sky, attract swimmers, artists and other beachgoers to the popular public pools sited on the rocky areas of the surf-coast from Palm Beach in the north to Cronulla in the south. While undeniably 'wilder' than any inground or indoor pool, or any tidal pool in the more sheltered waters of Sydney's harbour, bays and rivers, these ocean pools host recreational and competitive swimming, learn-to-swim programs and treasured forms of wave-play. People even visit these 'wild' pools in bad weather, simply to admire the power of the storms and seas.

While ocean pools are not common in other Australian states or territories, they remain abundant in Sydney and along much of the New South Wales coast, [2] where they function both as public pools and as beach safety measures. While allowing waves to wash in, the walls of an ocean pool exclude large sharks. Even more importantly, ocean pools – freely accessible year-round at all hours – offer the pleasure of immersion in lively seawater that is sheltered from the rips along the surf beaches.[3] As Sherker and her colleagues noted in 2008, those rips still account for many of Australia's surf rescues and coastal deaths by drowning.

Sydney's rock baths, ocean pools and bogey holes

The terminology used for these pools does vary. While Sydneysiders often refer to these pools as 'rock baths', similar pools in Newcastle and on the New South Wales central coast are known as 'ocean baths'. [4] While coastal communities with ocean pools as their only or their oldest public pools often simply refer to them as pools or baths, less formalised ocean pools may be referred to as 'bogey holes'. To give but one example, the southern end of Sydney's Bronte Beach hosts both the formalised Bronte Baths and an adjacent ring-of-rocks pool known as the Bronte Bogey Hole.

Ian Swift's exuberant artworks highlight the diversity of Sydney's ocean pools. [5] Despite site constraints on pool sizes and shapes, ocean pools developed in the twentieth rather than the nineteenth century are far more likely to be readily viewed and accessed from the beach, and to either include a children's pool or to be located near a children's pool. While all the ocean pools at Cronulla and on Sydney's northern beaches were developed during the twentieth century, development of ocean pools along Sydney's eastern beaches began earlier.

Ocean pools in Sydney's colonial municipalities

By the late nineteenth century, the growing pollution of Sydney Harbour prompted increasing numbers of Sydneysiders to visit the three surf-coast municipalities, namely Manly, Waverley and Randwick. While the Municipality of Manly offered safe sea-bathing in its harbour baths, the safest sea-bathing available in the municipalities of Randwick and Waverley was in the natural and 'improved' pools on Coogee, Bronte and Bondi beaches. Though Newcastle and Wollongong have ocean pools decades older, those early Sydney ocean pools are widely acknowledged as having played significant roles in nurturing Australia's beach cultures, [6] swimming cultures, [7] and surf lifesaving movement. [8]

As [media]few people then wore bathing costumes, safeguarding the respectability of sea-bathers in the colonial municipalities involved the provision of gender-segregated sea-baths that adequately screened bathers from public view in daylight hours. By the 1880s, Randwick's Coogee Bay had a women's pool on one side of the bay and a men's pool on the other side. Both of Coogee's ocean pools remained recreational spaces, because the home pool for the Randwick & Coogee Amateur Swimming Club, formed in 1896, was located within the off-beach Coogee Aquarium. [9]

Within the Waverley municipality, separate hours were allocated for men's bathing and women's bathing at the supervised, pay-to-use ocean pools developed at Bondi and Bronte, and all baths patrons were required to wear bathing costumes. As the municipality of Waverley had no other public baths, men's swimming clubs based themselves at both the Bondi Baths and the Bronte Baths. A turning board had to be installed to define a rectangular racing course with the non-rectangular Bronte Baths.

The 1890s club swimming carnivals at the Bondi and Bronte pools included men's swimming, diving events, water polo matches, as well as popular novelty events. Women's swimming events remained novel in colonial New South Wales, even after the New South Wales government schools and private schools began offering learn-to-swim programs for boys and girls.

Phillips has discussed the significance of the Bronte and Bondi Baths for both the development of competitive swimming and the Australian crawl. [10] As Rockwell suggested, swimming and playing water-polo in ocean pools cultivated skills relevant to saving lives in both stillwater and the surf . [11] The centenary history of Australian surf life-saving acknowledged that the Bronte and Bondi Baths also hosted Australia's earliest lifesaving classes, and highlighted their role in the development of life-saving practices more relevant to surf beaches. [12]

Pool and surf cultures 1901–12

The demand for ready access to ocean pools did not disappear when Sydney's surf-coast municipalities permitted daylight bathing in public view, provided bathers wore approved costumes. As the safer environment of the ocean pool still appealed to so many beachgoers, Coogee Bay acquired a third ocean pool, only a few years after the introduction of legalised daylight bathing.

[media]Wylie's Baths, a rare example of an ocean pool created as a private enterprise, opened at Coogee in 1907 as a gender-segregated, pay-to-swim pool. During the decades when sunbathing in public view remained prohibited, its change sheds offered a valued venue for sunbathing. Facing competition from Coogee's long-established men's and women's pools, as well as the nearby surf beach, where mixed bathing was gaining acceptance as a safety measure, Wylie's became one of the first ocean pools to offer mixed or family bathing. By contrast, the older pay-to-swim ocean pools at Coogee, Bronte and Bondi remained gender-segregated for several more decades.

Dissatisfaction with the management of beach and public baths by coastal municipalities fuelled demands for safe but less crowded, less regulated and less expensive venues for bathing, swimming and sunbathing. A reorganisation of local government arrangements in New South Wales in 1906 created a new type of local government body known as shire councils, with responsibilities for beaches and public baths in their council areas. Warringah Shire then included all of the Sydney beaches north of the Manly municipality, while Cronulla's beaches fell within Sutherland Shire.

Unlike Sydney's established coastal municipalities, these new coastal shires had no established tradition of gender-segregated bathing or supervised, pay-to-use ocean pools. Their residents, ratepayers and regular beachgoers did, however, have an interest in improving beach safety and providing safe, affordable facilities for bathing and for school, club and recreational swimming. Sutherland Shire residents, keen to improve their preferred bathing places, developed pools at Cronulla's Oak Park and Shelly Beach. Local action also developed ocean pools within Warringah Shire. All the ocean pools created in these shires were unsupervised and accessible from the beaches by anyone at any time at no charge. Warringah Shire's ocean pools also generally had close relationships with nearby surf lifesaving clubs.

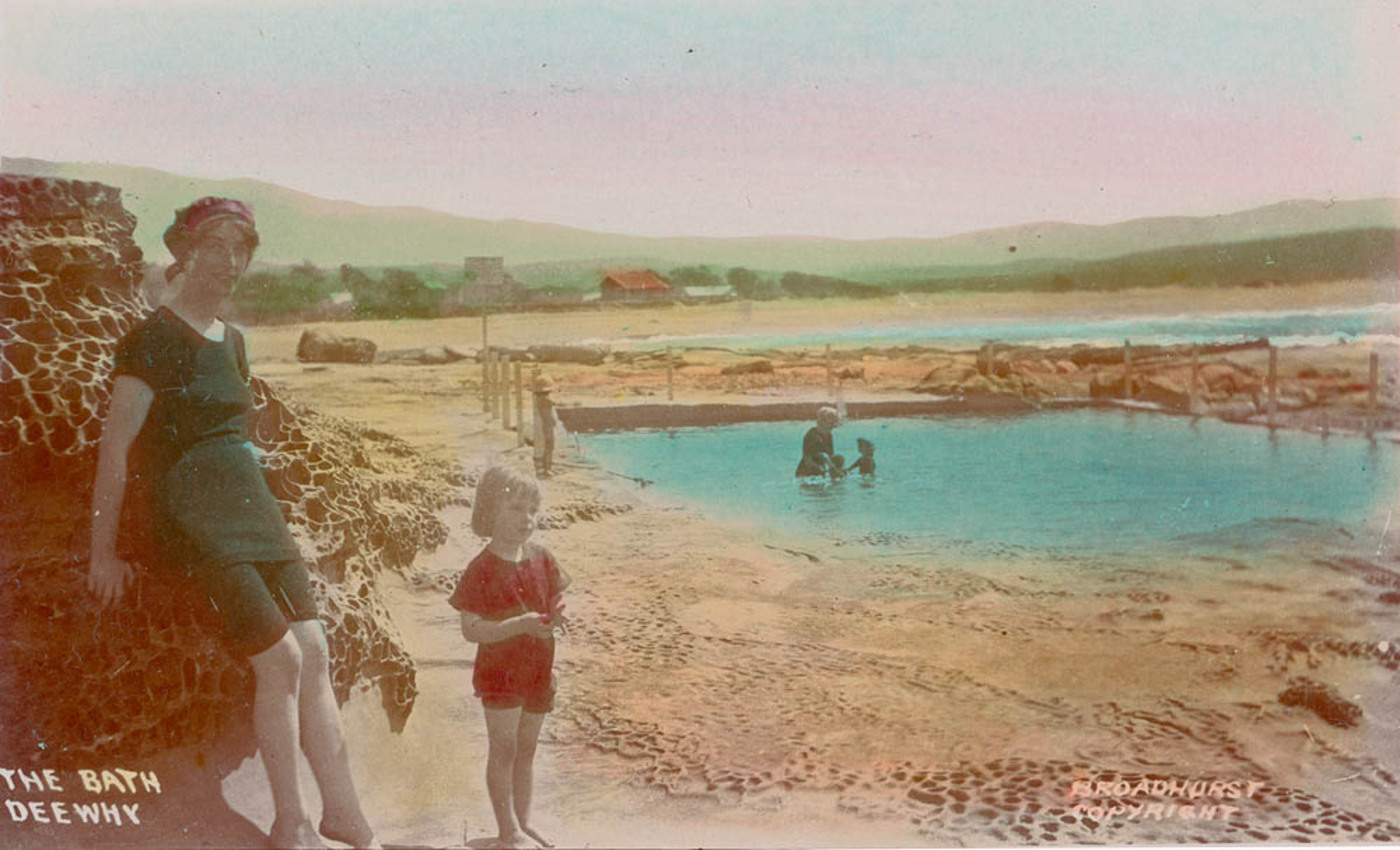

[media]Formally organised surf lifesaving clubs had begun patrolling Sydney's most popular surf beaches in daylight hours from 1907. As the surf lifesavers were volunteers, their patrols were usually limited to weekends and public holidays, which meant ocean pools still provided beachgoers with the best ongoing protection against sharks and rips. While the surf lifesaving clubs at Bondi and Bronte already had access to convenient ocean pools, other Sydney surf clubs, such as the Dee Why surf lifesaving club on the northern beaches, were involved in developing ocean pools. These new ocean pools provided recreational venues and training facilities for surf club members and beachgoers, as well as hosting competitive swimming and diving events and learn-to-swim programs.

Increasing numbers of men, women and children were taking part in amateur or professional events at ocean baths. While women's swimming clubs remained less common than men's swimming clubs, separate amateur swimming clubs for men and women were based at the Bondi Baths from 1907 until 1912. The Bronte Baths hosted both amateur and professional competitive swimming.

Development of ocean pools 1914–1960s

A few years after the New South Wales government endorsed mixed bathing at surf beaches, Sydney's surf clubs ceased accepting women as full members. This meant that men's enlistments for war service during World War I depleted both the men's swimming clubs and the surf lifesaving clubs. Women's competitive swimming was able to continue during the war years at the ocean pools that remained Sydney's most reliable beach safety measure.

During the interwar years, Ladies Amateur Swimming Clubs operated at ocean pools on Sydney's northern and eastern beaches and both the number of Sydney's ocean pools and the number of swimming clubs they hosted increased. [13] During the depression of the 1930s, unemployment relief schemes and public works schemes allowed new and less affluent coastal communities to acquire previously unaffordable ocean pools. With the assistance of community fundraising, Warringah Shire had already developed nine ocean pools by the time its North Narrabeen pool opened.

While the new ocean pools showed little standardisation of size, shape or facilities, none were gender-segregated. The North Narrabeen Pool was magnificently large compared to Manly's tiny Fairy Bower pool. While some ocean pools had clubhouses and dressing pavilions, Sutherland Shire Council expected patrons of the new pools on the rock platform between the North Cronulla and South Cronulla beaches to use the dressing facilities at the nearby surf beaches.

All these new no-charge, unsupervised pools were major visitor attractions adding to the appeal of surfside council camping grounds, coastal guesthouses, hotels and holiday homes as well as venues for recreational and competitive swimming. During those interwar years, night-bathing under lights drew people to Cronulla's main ocean pool in summer. Summer even ceased to be the only swimming season once the Bronte Splashers and the Bondi Icebergs began using their ocean pools for winter swimming competitions.

The ocean pools on Sydney's northern beaches were particularly memorable recreational and learn-to-swim venues for country children staying at the Stewart House Preventorium or taking part in other social tourism programs, such as the Royal Far West Children's Health Scheme. Sydney's ocean pools forged further links with country communities in the late 1930s, when members of the Bondi and Bronte Amateur swimming clubs spearheaded a free, state-wide, learn-to-swim campaign, that saw members of Sydney's swimming clubs giving swimming instruction in country areas.

Though interwar efforts to protect beachgoers against shark attacks expanded beyond ocean pools and patrolled beaches to include aerial patrols and the introduction of shark meshing at all of Sydney's metropolitan beaches, none of these additional measures diminished the support for ocean pools. Instead, the absence of surf lifesavers and the abandonment of aerial patrols and shark meshing during the war years highlighted the value of ocean pools as durable beach safety measures.

As barbed war disappeared from postwar Sydney beaches, shark meshing and beach patrols resumed and new ocean pools were developed. Club competition at ocean pools and the innovative coaching program developed by Forbes Carlile and Frank Cotton for the Palm Beach Amateur Swimming Club contributed to the postwar success of Australia's Olympic swimmers. [14] Those successes further stimulated efforts to redevelop ocean pools to Olympic standards and to develop more non-tidal pools. Ocean pools proved less seasonal than inground pools, which were usually drained over winter. Despite providing year-round swimming venues, Sydney's ocean baths nevertheless remained primarily recreational venues, playgrounds rather than sports arenas.

Sydney's ocean pools since the 1970s

From the 1970s through to the 1990s, the evident pollution of Sydney's eastern beaches by sewage and industrial waste decreased support for development of ocean pools and fuelled concerns for the environment, as well as construction of non-tidal public and private swimming pools. Nurses at Sydney's Prince Henry Hospital raised funds to develop a new swimming pool, because pollution from sewage outfall at Malabar had made the hospital's ocean pool at Little Bay unfit for use by the 1970s. [15] Only after the development of deep ocean outfalls for Sydney's sewage system in the 1990s had greatly improved the quality of Sydney's coastal waters was the Malabar ocean pool sited on Long Bay opposite Sydney's main sewage treatment plant redeveloped and reopened.

Even amid those water quality concerns, year-round use of Sydney's ocean pool was increasing due to enthusiasm for fitness swimming and winter swimming clubs. Improved access to other public or private pools did not eliminate demands for access to ocean pools. Booth mentioned that complaints that the film crew impeded access to both the beach and the rock pool helped fuel the local backlash against the use of Avalon Beach by the Baywatch film crew. [16] Other evidence of the importance placed on ready access to ocean pools includes efforts to make Sydney's ocean pools more accessible for people with injuries or disabilities.

Ian McShane has discussed the widespread pressures since the 1980s to replace seasonal public pools with year-round, multi-purpose, supervised pay-to-use leisure facilities and the local campaigns to ensure continued operation of specific public pools in Victoria. [17] Perceived threats to Sydney's older ocean pools have likewise triggered extensive campaigns to ensure those pools continue to operate and meet the expectations of their patrons and supporters. Eileen Slarke documented the long campaign to have Wylie's Baths reopened and refurbished. [18] Kurt Iveson discussed the successful campaign to ensure Coogee's McIvers Baths remained allocated solely for the use of women and children. [19] Malcolm Andrews has documented the Bondi Icebergs winter swimming club's efforts to upgrade their home pool and take charge of its future. [20]

Images of Sydney's ocean pool in recent exhibitions by photographers and other artists have directed attention back to the convivial but respectful relationships that an ocean pool can foster with the sea, marine life and the people in and around such pools. In those relatively wild swimming environments, encounters with bluebottles, seaweed, sea urchins, shells, sharp rocks and slippery rocks have never been unusual, and swimmers are sometimes washed out of the pools.

The increasing number of warning signs at the ocean pool therefore testify most strongly to growing community and insurance company expectations of absolute (rather than relative) safety, and a failure to appreciate the difference between controlled swimming environments and those catering for 'wild' swimming. While springboards have been removed from ocean pool and other public pools on health and safety grounds, people at ocean pools still walk on slimy surfaces, jump from railings, rocks and cliffs, get washed against rocks or out of the pools, and some are injured.

Although recent changes to the state's civil liability law have now clarified the right to engage in 'risky' recreation, ensuring future generations can enjoy Sydney's ocean pools may require more appropriate management of visitor expectations. At present, anyone unfamiliar with sea-baths and more accustomed to reading signs than surf, can easily fail to recognise ocean pools as safer recreational environments than unpatrolled, rip-prone surf beaches. Promoting Sydney's ocean pools as environmentally friendly 'wild swimming' environments would cultivate more realistic assessments of their benefits, hazards and heritage status. No other type of public pool so strongly links the suburban and the sublime.

References

M Andrews, Bondi Icebergs: an Australian icon: the easiest swimming club in the world to join ... and the hardest to remain a member, BB International, St Peters, New South Wales, 2004

H Brombey and M Daly, Randwick & Coogee Amateur Swimming Club: 1896–1996, Randwick & Coogee Amateur Swimming Club, Sydney, 1995

D Booth, Australian beach cultures: the history of sun, sand, and surf, Frank Cass, London, 2001

M Cordia, Nurses at Little Bay, 2nd edition, Prince Henry Hospital Trained Nurses' Association, Sydney, 1995

LF Huntsman, Sand in our souls: The beach in Australian history, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South Victoria, 2001

K Iveson, 'Justifying exclusion: the politics of public space and the dispute over access to McIvers Ladies Baths, Sydney', Gender, Place and Culture, vol 10, no 3, 2003, pp 215–228

E Jaggard (ed), Between the flags: one hundred summers of Australian surf lifesaving, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2007

M Keeble, Bondi Amateur Swimming Club, a history, 1892-1992, Bondi Amateur Swimming Club, [Bondi NSW] 1992

I McShane, 'The past and future of local swimming pools', Journal of Australian Studies, vol 33, no 2, 2009, pp 195–208

MG Phillips, Swimming Australia: one hundred years, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2008

C Proctor and A Swaffer, Sydney's best beaches and rock baths: the full-colour guide to over 90 fantastic destinations, Woodslane Pty Limited, [Sydney], 2009

New South Wales Ocean Baths website, http://www.nswoceanbaths.info, viewed 18 April 2010

K Rew, Wild swim: River, lake, lido and sea: the best places to swim outdoors in Britain, Guardianbooks, London, 2008

T Rockwell, Water warriors: chronicle of Australian water polo, Pegasus, Edgecliff NSW, 2008

S Sherker, R Brander, C Finch, and J Hatfield, 'Why Australian needs an effective national campaign to reduce coastal drowning', Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, vol 11 no 2, 2008, pp 81–83

AD Short, Beaches of the New South Wales coast: a guide to their nature, characteristics, surf and safety, Australian Beach Safety and Management Program, Beaconsfield NSW, 1993

E Slarke, A century of Wylie's Baths, Coogee: a cultural history, Wylies Baths Trust, Coogee NSW, 2001

I Swift, Sydney's ocean baths and other musings, Katooma Fine Art, Katoomba NSW, 2005

I Wye, '80 years on': The Dee Why Ladies Amateur Swimming Club, 1922–2002, Dee Why Ladies Amateur Swimming Club, Dee Why NSW, 2002

Notes

[1] K Rew, Wild swim: River, lake, lido and sea: the best places to swim outdoors in Britain, Guardianbooks, London, 2008

[2] New South Wales Ocean Baths website, http://www.nswoceanbaths.info, viewed 18 April 2010

[3] AD Short, Beaches of the New South Wales coast: a guide to their nature, characteristics, surf and safety, Australian Beach Safety and Management Program, Beaconsfield NSW, 1993

[4] C Proctor and A Swaffer, Sydney's best beaches and rock baths: the full-colour guide to over 90 fantastic destinations, Woodslane Pty Limited, [Sydney], 2009

[5] I Swift, Sydney's ocean baths and other musings, Katooma Fine Art, Katoomba NSW, 2005

[6] D Booth, Australian beach cultures: the history of sun, sand, and surf, Frank Cass, London, 2001; LF Huntsman, Sand in our souls: The beach in Australian history, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South Victoria, 2001

[7] MG Phillips, Swimming Australia: one hundred years, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2008

[8] E Jaggard (ed), Between the flags: one hundred summers of Australian surf lifesaving, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2007

[9] H Brombey and M Daly, Randwick & Coogee Amateur Swimming Club: 1896–1996, Randwick & Coogee Amateur Swimming Club, Sydney, 1995

[10] MG Phillips, Swimming Australia: one hundred years, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2008

[11] T Rockwell, Water warriors: chronicle of Australian water polo, Pegasus, Edgecliff NSW, 2008

[12] E Jaggard (ed), Between the flags: one hundred summers of Australian surf lifesaving, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2007

[13] M Keeble, Bondi Amateur Swimming Club, a history, 1892-1992, Bondi Amateur Swimming Club, [Bondi NSW] 1992; I Wye, '80 years on': The Dee Why Ladies Amateur Swimming Club, 1922–2002, Dee Why Ladies Amateur Swimming Club, Dee Why NSW, 2002

[14] MG Phillips, Swimming Australia: one hundred years, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2008 pp 37, 77

[15] M Cordia, Nurses at Little Bay, 2nd edition, Prince Henry Hospital Trained Nurses' Association, Sydney, 1995, p 317

[16] D Booth, Australian beach cultures: the history of sun, sand, and surf, Frank Cass, London, 2001

[17] I McShane, 'The past and future of local swimming pools', Journal of Australian Studies, vol 33, no 2, 2009, pp 195–208

[18] E Slarke, A century of Wylie's Baths, Coogee: a cultural history, Wylies Baths Trust, Coogee NSW, 2001

[19] K Iveson, 'Justifying exclusion: the politics of public space and the dispute over access to McIvers Ladies Baths, Sydney', Gender, Place and Culture, vol 10, no 3, 2003, pp 215–228

[20] M Andrews, Bondi Icebergs: an Australian icon: the easiest swimming club in the world to join … and the hardest to remain a member, BB International, St Peters, New South Wales, 2004

.