The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Hammond, Robert Brodribb Stewart

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Hammond, Robert Brodribb Stuart

Robert Hammond was [media]born at Brighton, Victoria, on 12 June 1870, the seventh of ten children. His mother, Jessie Duncan, was a Scotswoman, and his father, Robert Kennedy Hammond, was a stock and station agent from New South Wales. He attended Melbourne Church of England Grammar School and drank deeply of its culture of 'muscular Christianity'. An excellent footballer, young Hammond was part of Essendon's 1897 premiership-winning team, and achieved the honour of state selection.

In 1891, as a severe economic crisis brought ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ to its knees, Hammond heard the visiting Irish evangelist George C Grubb and committed his life to Jesus. Ordained into the Anglican ministry in 1894, he initially ministered in Melbourne and Gippsland, where he won respect from rougher men for his willingness to step into their shoes, even if it meant working three months down a mine, and for his ability to beat all challengers with a straight right fist.

Sydney bound

In 1899, Hammond moved to Sydney where he made a name as 'the mender of broken men'. After a short stint at St Mary's Balmain, he became curate of St Philip's Church Hill, a parish stretching down to the Darling Harbour docks with a large population of wharf labourers. While there, the burly 33-year-old married Jean Marion Anderson. A year later, in June 1905, she gave birth to a son. Bert struggled with an undiagnosed debility and, after just four weeks, died in his mother's arms. He was the Hammonds' only child. Jean grieved her loss at home; the bereaved clergyman threw himself into his work among the poor of the inner city.

For seven years from 1904, Hammond was organising missioner of the Mission Zone Fund, a new section of the Anglican Home Mission Society focused on redeeming the slum population of the inner city, where only 5 per cent of nominal Anglicans attended church services. As Mission Zone leader, Hammond visited thousands of private dwellings in the working-class areas of Woolloomooloo, Surry Hills, Newtown and Redfern, calling their inhabitants to both Christ and temperance. He held open air meetings, ran services in factories, and looked for new ways to use 'mission halls' and make them less like church buildings. [1] With a team of lay men and women, Hammond also visited the sick, consoled the dying and organised fête days to distribute donated goods and clothing. He raised money from the rich and compelled attention from the poor, once hooking a crowd of workers by describing 'a man who went on strike because wages were too high'. ('The wages of sin is death' as the New Testament puts it, and Jesus stepped in to pay the price.) By 1911, when Hammond resigned, the Mission Zone Fund had outstripped its parent society in meeting the complex needs of the inner city.

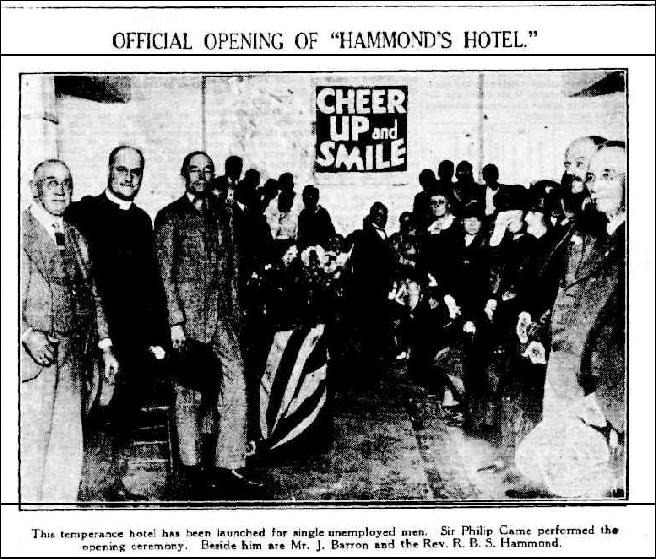

Hammond hotels

[media]With irrepressible energy and a determined preference for individual action, Hammond established a range of charitable ventures independently of the Sydney Diocese. In 1908, he opened his first 'Hammond hotel' for destitute men in an old warehouse in Newtown. A second soon followed, on Buckland Street, Chippendale, then a third in Surry Hills and a fourth by the docks at Darling Harbour. By 1933, the worst year of the Great Depression, there were eight 'Hammond hotels' that together accommodated more than 350 men, as well as a refuge for homeless families. A staunch prohibitionist, Hammond also founded a weekly newspaper, Grit , which urged its readers to temperance and hard work, and proclaimed the supreme importance of helping one's neighbour. From 1912, he made daily visits to the 'drunks' yard' at Central Police Court, where he interviewed down-and-out individuals waiting for their court appearances. Over the years, he personally spoke to as many as 100,000 people and convinced one in five of them to sign the temperance pledge. [2]

St Barnabas and the Brotherhood

[media]In 1918, nearing 50, Hammond shifted the focus of his parish work from St Simon's and St Jude's, Surry Hills, where he had been rector since 1909, to St Barnabas's, a dwindling parish centred on George Street West (later called Broadway). He quickly made it the centre of a vigorous ministry. He established the St Barnabas 'Brotherhood of Christian Men', whose members pledged to commit themselves to daily bible reading and prayer, to abstain from all intoxicating liquor, and to support the work of the Brotherhood in reaching more men. Its Wednesday night meetings gradually achieved a regular attendance of 200–300 and, over time, brought thousands to faith in Jesus. Among them was 'eternity man' Arthur Stace, who both embraced Christianity and gave up the grog upon first attending a Wednesday night meeting in August 1930. By 1943, more than 4,000 others had similarly signed the Brotherhood membership pledge. [3] Hammond's extraordinary success as an evangelist made him famous and, in his own forthright, inimitable style, he shared his ideas on 'reaching men' at several Australian preachers' conventions. [4]

Just as famously, Hammond transformed St Barnabas's into one of Sydney's primary centres of poor relief. Even before the Great Depression set in, the church's annual social service outlay exceeded £1,000, a figure unmatched by other Anglican parishes or agencies during the 1920s. During the crisis of the early 1930s, it boasted an Employment Bureau, an Emergency Depot and a soup kitchen that served thousands of meals a year. Hammond maintained these ministries, as well as the eight Hammond Hotels and the family refuge, with the help of parishioners and a large number of additional donors and volunteers – including Stace, whom Hammond placed in charge of the hotel in Buckland Street.

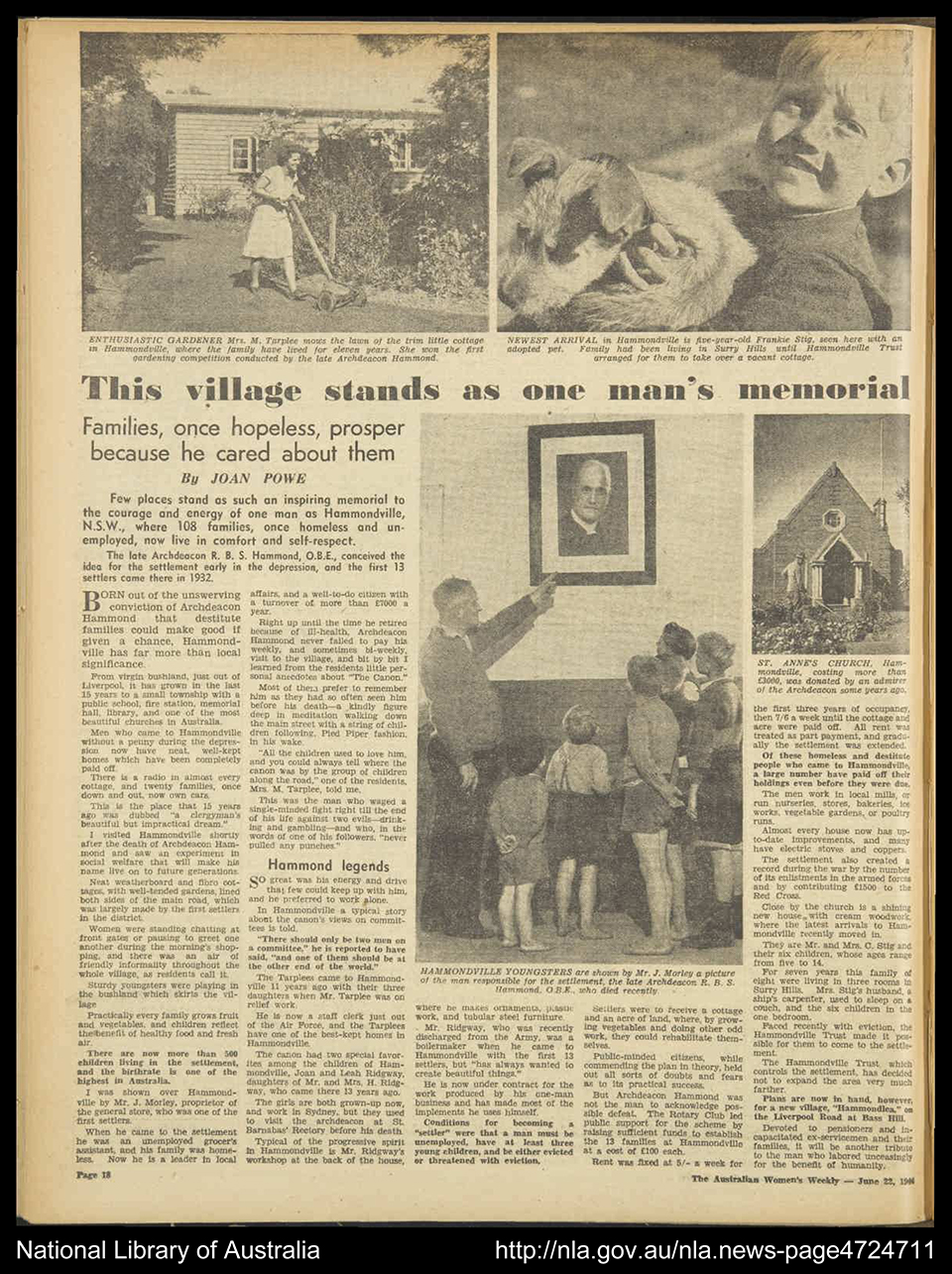

Hammondville begins

Hammond's most [media]imaginative and remarkable response to the Depression was the Pioneer Homes Scheme. At a time when the vast majority of workers lived in rented accommodation, widespread unemployment quickly snowballed into a crisis in housing. The government's limited support for the workless did not extend to rent assistance and, in 1932 alone, New South Wales courts issued more than 5,800 Orders of Ejectment against people chronically behind on rent. Some of the evicted moved in with relatives; numerous families were driven to shanty towns such as 'Happy Valley' and 'Hill 60' on the blustery shores of Botany Bay. By mid-1933, 33,000 homeless Australians lived in makeshift camps across the country.

[media]Hammond did not wait for government to act: with money raised by cashing his own life insurance policy, he purchased a tract of uncleared land five kilometres past Liverpool and established his own settlement for unemployed workers and their evicted families. He arranged for the construction of several basic wooden cottages, each with an acre of land, and offered them to unemployed couples with three or more children. He expected the scheme's participants to cultivate their gardens and to make modest but regular payments towards the purchase of their land and cottage. The goal, as he put it grandly, was nothing less than the salvation of 'the woman from the fear of eviction, the man from the curse of doing nothing, and the children from the calamity of being under-nourished.' [media]In just five and a half years, to early 1938, the settlement grew from nine to 110 wooden cottages and acquired a primary school, a community hall and a number of shops: the nucleus of what is now the suburb of Hammondville.

Practical Christianity

Robert Hammond's ministry expressed [media]particular ideas about charity. His 'practical Christianity', as he called it, set him apart from more conservative evangelicals who viewed charity as a mere adornment to the verbal proclamation of the gospel, or as a tool for individual conversion and moral reform. It also differentiated him from those in the Catholic and Anglo-Catholic traditions, who tended to understand charity in the incarnational terms of 'offering something to Christ in the person of the poor', or pursue social justice on the basis of 'God's preferential option for the poor'. [5] Hammond was unconcerned with how 'deserving' or otherwise a person might be: as the slogan for his hotels explained, 'need is the latchkey.'

He was similarly uninterested in the reform of the economy and wider society. Hammond's goal and motivation was to live as a faithful disciple of Christ. 'There is no other reason than the one I give you,' he told hotel residents in 1933,

that anything I may be is a proof of my faith in Jesus Christ. His life impresses the whole wide world... I have tried in some small way to imitate His wonderful example. [6]

Hammond's sense of God's unfailing goodness transcended both the private tragedy of losing a child and the public calamity of the Depression, and compelled him to show radical kindness as an act of personal devotion to Jesus. 'I trace all the good things I enjoy back to God, and would have Him acknowledged as the source of all things.'

Hammond's extraordinary contribution to his church and wider community confirmed him as the best-known and most effective Anglican minister in Sydney, unmatched in the first half of the twentieth century. His achievements were formally recognised within his denomination by his appointment as a Canon of the Cathedral (1931) and Archdeacon of Redfern (1939). He was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1937.

Hammond's habitual generosity left him without significant savings, but a grateful Sydney public showed its appreciation upon his retirement from St Barnabas in 1943, subscribing £3,000 for the purchase of a house at Beecroft in which the ailing minister spent his final years. His wife Jean had passed away in June 1943. In light of his own increasing frailty, Hammond subsequently married a 39-year-old nursing sister, Audrey Spence, who cared for him until his death. Hammond died on 12 May 1946, at the age of 75. His relief programs were continued by their staff and volunteers. Hammond's Social Services, as they were collectively known, later reintegrated with the Anglican Home Mission Society. Hammond's Pioneer Homes endured as a company in its own right. Under the name HammondCare, it remains a dynamic, independent Christian charity.

References

Bernard G Judd, He That Doeth: the life of Archdeacon RBS Hammond OBE, Marshall, Morgan & Scott, London, 1951

Stephen Judd, 'Hammond, RBS', in Brian Dickey (ed), Australian Dictionary of Evangelical Biography, Evangelical History Association, Sydney, 1994, pp 148–150

Stephen Judd and Kenneth Cable, Sydney Anglicans: a history of the Diocese, Anglican Information Office, Sydney 1987

Joan Mansfield, 'Hammond, Robert Brodribb Stewart (1870–1946)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 9, 1983, online at National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hammond-robert-brodribb-stewart-6543/text11243, viewed 21 November 2012

Notes

[1] 'Reaching the Masses', Sydney Morning Herald, 21 July 1908, p 12

[2] Joan Mansfield, 'Hammond, Robert Brodribb Stewart (1870–1946)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hammond-robert-brodribb-stewart-6543/text11243, accessed 21 November 2012; see also '50,000th pledge at "drunks'court"', Argus, 9 November 1935, p 24, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11853152, viewed 22 November 2012

[3] Bernard G Judd, He That Doeth: the life of Archdeacon RBS Hammond OBE, Marshall, Morgan & Scott, London, 1951, p 72

[4] 'Reaching the Masses: The Church Society Mission Zone Fund Conference', Sydney Morning Herald, 21 July 1908, p 12; 'Address by Mr Hammond' [Marrickville Baptist monthly men's meeting], Sydney Morning Herald, 19 November 1923, p 10; 'Local Preachers Convention,' Adelaide Advertiser, 21 May 1930, p16; 'Canon Hammond and Homes For Homeless: Laymen's Convention At Pirie Street,' Adelaide Advertiser, 12 November 1934, p 17

[5] John Murphy, 'Suffering, Vice and Justice: Religious Imaginaries and Welfare Agencies in Post-war Melbourne,' Journal of Religious History, vol 31 no 3, 2007, p 288

[6] 'Hammond Hotels' Guests register their appreciation of 'The Chief'', Grit, 6 July 1933, p 7