The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Working the Tides

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The maritime cultural landscape linking the Woronora and Brisbane Water mills

Traditionally, the Georges River was an important focal point for Aboriginal life and culture in the southern Sydney region, offering food, transport and dreamtime links. Several major language groups existed along the river: the Eora to the east, the Dharug to the west, north and north-east, the Dharawal to the south and the Gandangarra in the far south-west. By the early 1800s, the Georges River was being used as a water highway with white settlers on its fertile river flats taking their goods to market and bringing in supplies through Botany Bay.

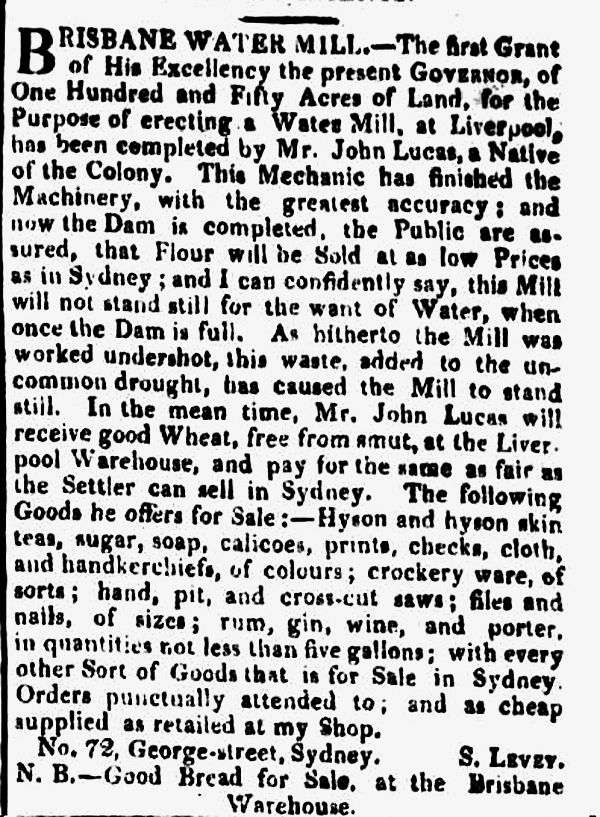

During the 1820s the colonial miller, John Lucas, built two undershot watermills on the Georges River. The Brisbane Mill was built in 1822 and the Woronora Mill was constructed in 1825. The mills operated at least until 1828 when Lucas was declared bankrupt, a victim of droughts, floods, the loss of his family boat, Olivia , and possibly mismanagement. [1]

The Brisbane Mill was just above the head of navigation of Williams Creek and the Woronora Mill was situated just above the head of navigation of the Woronora River. Although it is only 10 kilometres in a straight line between Lucas' two mills, and approximately 13 kilometres through the bush, the terrain is steep and rugged. The descent of over 110 metres to the Woronora River would have made the cartage of large and heavy items difficult. [2] In 1843 Sir Thomas Mitchell struggled to build a road down to, and across, the Woronora near the Woronora Mill; it was eventually abandoned because of the steepness of the terrain.

Mills in the Georges River basin

[media]Until 1832 there was no customs presence in Botany Bay. By operating his mills in the Georges River, Lucas avoided duty on all incoming wheat which was only collected at Port Jackson. [3] To avoid paying duty on the flour he produced, Lucas shipped his flour in small boats to Liverpool then used land transport to the markets in Sydney. It was an unpredictable market, vulnerable to the vagaries of the weather, and wheat varied in price considerably. A survey published in the Colonial Times, in April 1831 gave the average monthly price of wheat paid in Sydney for 1828; it varied between a minimum of 8 shillings and 9 pence per bushel in January to 15 shillings in July. [4] Although Lucas' flour could have gone to the Sydney market all of the way by boat, in 1827 the duty on flour was 5 shillings per hundredweight (1 hundredweight = 50.8kg). [5] With flour costing approximately 20 shillings per hundredweight, this duty was approximately 25 percent of the price. From 1813 a road connected Liverpool with Sydney, a distance of 34 kilometres. By delivering wheat to Sydney by road, Lucas could avoid paying any duty and so had an economic advantage over millers operating in Sydney.

Drought and drink

John Lucas owned his two water mills during a succession of droughts that dominated New South Wales during the 1820s. Rainfall records were poorly kept in this decade but both contemporary observers and the newspapers of the day constantly referred to the drought conditions in the colony. [6] On Thursday 1 April 1824, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reporting on the Brisbane Mill stated that '…the uncommon drought has caused the Mill to stand still'. [7] Despite the difficulties of the weather, Sydney relied on wheat as a major food source and it was frequently imported in times of shortage. Wheat was brought into the colony from South America in 1828 and from India in 1829. [8] It was also transported from Five Islands, the name now given to the Lake Illawarra district near Wollongong. [9] This wheat was certainly closer to Lucas' mills than the Sydney market and small boats could easily have made the trip and possibly delivered the wheat to the Brisbane Mill's door.

Historian Pauline Curby has suggested that Lucas may have been engaged in the production of illicit alcohol for the thirsty settlers at Five Islands. The remote location of the Woronora Mill and the regular boat transport to Five Islands would certainly have made this activity possible. [10] Moreover, in February 1821, The Sydney Gazette and New South Advertiser listed John Lucas as the owner of the Black Swan Inn in George Street, Sydney – another possible outlet for illicit alcohol, a phenomenon not uncommon in the colony at this time. [11]

Sourcing wheat

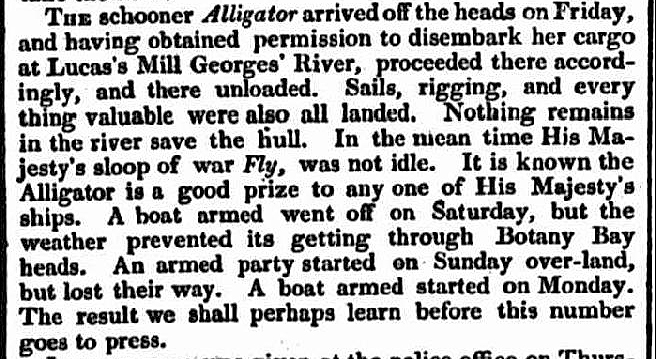

Wheat was often imported from Port Dalrymple at Launceston in Van Diemen's Land; indeed, much of New South Wales' wheat was supplied by the southern colony during the 1820s. According to Broadbent and Hughes, a strong trade in grain from Van Diemen's Land had developed by 1816 and '…by 1819 half the islands crop went regularly to Sydney.' [12] Much of Lucas' wheat probably came from the sister colony as the Lucas family was heavily involved with this particular grain trade. Contemporary shipping news details the movement of the Lucas' family schooner Olivia, which included many trips from Tasmania to his mills on the Georges River with a cargo of wheat. [13] The Olivia's burden of 60 tons was close to the 140 ton displacement maximum that could navigate the Georges River. [14] A ship of 60 ton burden would probably have a length of 17 metres and could have made deliveries to the door of the Brisbane Mill. [15] In September 1826, The Monitor [media]reported that the schooner, Alligator, of 198 tons burden and approximately 27 metres in length, had attempted to deliver a cargo of wheat from Port Dalrymple to John Lucas' mill. [16] This schooner predictably grounded in the shallow entrance of the Georges River; a farcical story of the Alligator's arrest and seizure resulted. [17]

A small amount of wheat was transported from 'Bottle Forest' an area known today as Heathcote. [18] The distance in a straight line from the farms in the area to the mills on the Georges River is approximately 3.8 kilometres but the climb down to the mill with wheat, and the return trip carrying flour, would have been difficult. The area under cultivation at Bottle Forest was also small and so could not have supplied significant amounts of wheat to Lucas' watermills. Wheat from 'Little Forest', a 700 acre (approximately 283 hectares) land grant held by a Mr David Duncomb and measuring approximately three kilometres (in a straight line) North West of the Woronora Mill, might have been another local source of wheat for Lucas' mills, although historians are somewhat doubtful, again due to the steepness of the terrain. [19]

Liverpool was also a major wheat growing area in the 1820s. [20] Thomas Rowley, Lucas' brother-in -law, is listed in The Sydney Gazette and New South Advertiser in January 1821 as a supplier of wheat to the government stores in Liverpool, together with twelve other farmers in the Liverpool area. [21] Lucas' own land on Williams Creek may also have supplied wheat. The Lucas name appeared on a list of suppliers of wheat to the Government Stores in The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser in May 1823. [22] This makes it highly probable that local wheat was indeed supplying the Brisbane Mill and may have been one of its main sources.

Moving goods along the Georges River

In 2013 a team of researchers completed a voyage between the Woronora and Brisbane mills in a sail and oar driven craft to better understand the difficulties and time taken of river voyages between John Lucas' mills. The journey was completed in four stages, [23] using a six metre craft similar to those used in the 1820s. [24] The journey was made by working the tides and aided by oar and sail power, the methods most commonly used for moving small working crafts in the nineteenth century. [25]

Images from the early 1800s suggest that boats using the Georges River system were of clinker construction with long fixed shallow keels, rowed with a pair(s) of oars and with a lugsail rig. It is also possible that goods were moved to and from the mills on barges. The ability to row or sail a barge is limited but they have a shallow draft and can carry a large load. They too would rely on the tides, polling or being towed by another boat. Sailing a shallow draft boat is feasible in much of the Georges River but difficult in the Woronora River and Williams Creek because of the narrowing of the river and high river banks reducing the wind. Also, the distance between the two mills and between Botany Bay and the Brisbane Mill is considerable and may have been too long a journey for a single tide.

Working the tides is a time honoured method of moving along a river estuary. The boat simply travels with the tides as it flows up and down the river and is anchored when the tide is contrary to the desired direction of travel. Where the tidal flow is swift, this method is efficient, but at the headwaters of the estuaries, where Lucas' Mills were located, the tidal flow is reduced to nothing. The tidal flow also depends on the relative heights of the tides which vary from 80 to 150 centimetres in the Georges River estuary.

There are many historic examples of boats using the tides as their only means of propulsion. In 1836 the bridge builder, David Lennox, built a stone bridge over Prospect Creek, not far from Lucas' Brisbane Mill. The stone was transported by barges from a quarry on the Georges River at a distance of 11 kilometres using the tide. The same quarry supplied stone for Lennox's Weir at Liverpool, the head of navigation of the Georges River, also by barges. [26]

Sailing is a most efficient means of propulsion and works well in wide estuaries and bays. Unfortunately the region of Lucas' mills has narrow and high river sides, rising to over 100 meters in places. This shelters the river from wind and funnels what wind there is down the river valley, which can be undesirable if the wind is contrary to the direction of intended travel. For much of the voyage between the mills, the river is too narrow to tack back and forth. Boats in the 1820s, with their shallow fixed keels and inferior sails, would not have been as efficient windward as more modern craft.

Conclusion

Given the location of Lucas' mills and the waterways connecting them, some combination of working the tides and sailing must have been employed. It is impossible to travel along a narrow river against a strong headwind indicating that, in the nineteenth century, trips may have been undertaken early in the morning, at dusk, or at night when the wind generally drops. [27] Polling is efficient in a shallow river with a sand or rock bottom but impossible in deep water or thick mud. At times of heavy rain, neither of the mills could have been approached by boat because of the volume of fresh water overpowering the tide. As the 1820s was a period dominated by drought this was unlikely to have caused problems in the movement of flour and goods along the Georges River. It seems likely that downstream from the mills the tides were probably the most important method with sailing becoming increasingly important as the river widened. Polling was most likely used at the headwaters of the rivers near the mills.

In the 1820s early colonial entrepreneurs used the fertile lands along and the waterways of the Georges River for transport and commerce, closely connecting the area with Liverpool, Botany Bay and Sydney. Yet the complexities faced by John Lucas in building and then running his two water mills, sourcing wheat and delivering flour to the commercial market should not be underestimated. His business and livelihood was very much at the mercy of the terrain, the weather, the wind, the tides and the wider colonial market conditions. The reasons for his failure and bankruptcy in 1828 were largely due to factors beyond his control. Further archaeological research and investigations at the mill sites may shed more light on the mills operations and the lifeway's and transportation patterns of the people who lived and worked there.

References

James Broadbent and Joy Hughes, The Age of Macquarie, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1992

Pauline Curby, 'Lucas' Mill', Sutherland Shire Historical Society Inc Bulletin, vol 7, no 2, May 2004

David Day, Smugglers and Sailors: The Customs History of Australia 1788 – 1901, Canberra, AGPS Press, 1992

Pam Forbes, Unpublished research statistically relating the tonnage of wooden sailing ships to their length, 2012

Pam Forbes and Greg Jackson, 'The Watermills of John Lucas: Part 3', Sutherland Shire Historical Society Inc Bulletin, vol 16, no 1, February 2013

Pam Forbes and Greg Jackson, 'The Watermills of John Lucas: Part 2', Sutherland Shire Historical Society Inc Bulletin, vol 15, no 4, November 2012

Greg Jackson, 'The Strange Tale of the Alligator', Sutherland Shire Historical Society Inc Bulletin, vol 14 no 1, February 2011

Patrick Kennedy, From Bottle Forest to Heathcote, Robert Burton Printers, Australia, 1999

Robert Montgomery Martin, History of Austral-Asia: Comprising New South Wales, Van Diemen's Island Swan River, South Australia, etc, Whittaker and Co, London, 1839

Notes

[1] See P Forbes and G Jackson, 'The Watermills of John Lucas: Part 3', Sutherland Shire Historical Society Inc Bulletin, vol 16, no 1, February 2013, pp 23–29; P Forbes and G Jackson, 'The Watermills of John Lucas: Part 2', Sutherland Shire Historical Society Inc Bulletin, vol 15, no 4, November 2012, pp 20–25

[2] See NSW Department of Land and Property Information, Topographic and Orthophoto, Map 9129 4N, Port Hacking, 2001

[3] David Day, Smugglers and Sailors: The Customs History of Australia 1788–1901, Canberra, AGPS Press, 1992

[4] The Colonial Times, Tuesday 5 April 1831, p 2

[5] The Australian, 30 May 1827, p 3

[6] See The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 26 February 1824, p 2; The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 14 October 1824, p 2; and The Australian, Thursday 6 January 1825, p 3. In his book RM Martin talked about 'the great drought of 1827'. See History of Austral-Asia: Comprising New South Wales, Van Diemen's Island Swan River, South Australia, etc, Whittaker and Co, London, 1839, p 129

[7] The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 1 April 1824, p 4

[8] An article in The Sydney Monitor on Saturday 26 September 1829, p 4, lamented the importation of 20,000 bushels of wheat to the colony, mostly from India, and the effect this would have on local grain prices. The Monitor, on Monday 11 February 1828, p 4, noted the import of wheat from South America to the Sydney market. There is no evidence that any of this grain went directly to Lucas' mills but it is certainly possible

[9] The Sydney Monitor, Wednesday 6 January 1830, p 2, and The Sydney Monitor, Wednesday 29 September 1830, p 4, describe wheat production in the Five Islands region

[10] Pauline Curbie, 'Lucas' Mill', Sutherland Shire Historical Society Inc Bulletin, vol 7, no 2, May 2004, p 25

[11] The Sydney Gazette and New South Advertiser, Saturday 24 February 1821, p 2

[12] J Broadbent and J Hughes, The Age of Macquarie, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1992

[13] See The Australian, Wednesday 25 October 1826, p 3

[14] Office of Environment and Heritage, Heritage listing for Liverpool Weir, http://www.heritage.nsw.gov.au/07_subnav_04_2.cfm?Itemid=5060394, 2010, p 9, accessed 15 March 2012

[15] P Forbes, Unpublished research statistically relating the tonnage of wooden sailing ships to their length, 2012

[16] The Monitor, 1 September 1826, p 6; P Forbes, unpublished research statistically relating the tonnage of wooden sailing ships to their length, 2012

[17] See G Jackson, 'The Strange Tale of the Alligator', Sutherland Shire Historical Society Inc Bulletin vol 14, no 1, February 2011, pp 7–11

[18] P Kennedy describes wheat being grown in the Bottle Forest area and transported to Lucas' Woronora Mill for grinding. See P Kennedy, From Bottle Forest to Heathcote, Robert Burton Printers, Australia, 1999, p 48

[19] The Australian, Friday 23 September 1831, p 4, reported a land grant of 700 acres (approximately 283 hectares) for David Duncomb, although he may have occupied the land prior to this date. This land is approximately three kilometres (measured in a straight line) North West of the Woronora Mill. Some of the land is fertile shale soil and may have grown wheat but there is no evidence of him supplying Lucas' mill. Given the steep terrain it would have been a difficult journey and Parish Map 14065001 (NSW Department of Lands and Property Management Authority, nd) significantly shows Duncomb's private access road travelling along the ridge top past Lucas' land and descending to the Woronora several kilometres down-stream of the mill bypassing Lucas' Mill

[20] From 1813 a road connected Liverpool with Sydney at a distance of 34 kilometres. The distance in a straight line from the Brisbane Mill to the centre of Liverpool is approximately 5.5 kilometres over relatively flat country. However no bridge crossed the Georges River until the construction of the weir at Liverpool by Lennox in 1836 so it is likely that the transport of flour to Liverpool would have been by boat

[21] The Sydney Gazette and New South Advertiser, Saturday 6 January 1821, p 2

[22] The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 29 May 1823, p 1

[23] The statistics for the four part voyage from the Woronora Mill to the Brisbane Mill were; average speed, 3.5km/h; average tidal range, 1.06m; time taken, 7.75 hours; distance travelled, 27.2km; method of propulsion, tide, sail, sculling, oar, walking

[24] Although Mystra, the boat used by the research time, is modern there are similarities between her and the boats of the 1820's: Mystra's gaff rig is traditional although small colonial boats were more often lug sail rigged; her size of 5.5 meters and burden of about a ton would have been at the upper end of boats able to approach the Woronora Mill. Sometime in the 1930's the army cleared shoals known as 'The Needles' from the Woronora River. These rocks would have limited the draught of the boats that could approach the Woronora Mill and limited the times at which boats could have approached the mill near high tide.

[25] Mystra, the boat used in this voyage, was built from timber and epoxy by author Greg Jackson and was first launched in 2005. Mystras' statistics are: six metres LOA in length; two metres beam, modified dory hull, Gaff ketch rig; 500kg displacement: approximately 1 tonne burden; 0.2 metre draft (centreboard up), 1 metre (centreboard down); electric, 2HP auxiliary engine (not used in this project), Designed by Mike Roberts, Headland Boats Brisbane. Mystra can be powered by sailing, using her efficient gaff ketch rig, rowed using a single 3.3 metre sweep on the starboard side, skulled using the same large sweep in a rollick on the starboard transom, and polling. The Mystras' crew varied between three and five for the voyages. The authors would like to thank David Forbes (photography), Jane Rooke and Lloyd Hedges for assistance with the voyages, and Ben Wharton who accompanied them on all four voyages

[26] JM Antill, 'Lennox, David (1788–1873)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lennox-david-2350/text3071, accessed 27 January 2013

[27] A voyage between the Woronora and Brisbane mills would be possible on a single tide (just over 12 hours) as long as there were not strong headwinds or large amounts of fresh water coming down the rivers. A short stop would probably be necessary near Como to wait for the tide to change. A trip from the Woronora Mill to Botany Bay (21 kilometres) would be feasible in a six hour tidal event, especially if the boat employed had reasonable sailing characteristics. The trip from the Brisbane Mill to Botany Bay (28 kilometres) would probably require two tidal falls.