The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Kia ora!

![Detail from 'The town of Sydney in New South Wales' showing Māori chiefs, c1821 by Major James Taylor, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (V1/ca.1821/5 DETAIL])](https://s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/slnsw.dxd.dc.prod.dos.prod.assets/home-dos-files/2021/05/SLNSW-V1-1821-5-detail.jpg)

Detail from 'The town of Sydney in New South Wales' showing Māori chiefs, c1821 by Major James Taylor, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (V1/ca.1821/5 DETAIL])

New Zealand and New South Wales were once one colony, but on 3 May 1841 New Zealand was officially declared a British colony separate from New South Wales. This month it is the 180th anniversary of this decision that brought about two intertwined but distinct national stories. Listen to Mark and Marlene on 2SER here

Today Sydney enjoys close ties to New Zealand. It is our only international travel bubble option and remains a popular holiday destination. People come and go from both directions, with a large ex-pat community of New Zealanders in Sydney.

These connections go back to the first years of Sydney as a British outpost, maybe even earlier. Aboriginal and Māori stories hint at contact across the ditch before British arrivals, but we know for sure that Māori visitors were here by 1793, just five years after the First Fleet arrived.

In true colonial fashion, British ships visiting New Zealand’s Bay of Islands area kidnapped two Māori men, Tuki Tahua and Ngahuruhuru (also known as Huru) and took them to Norfolk Island to teach convicts how to weave flax for ships sails. Flax grew abundantly in New Zealand and would become a major trade item. The men did not traditionally weave flax and so could not help. Instead they were taken to Sydney, met Governor King and were returned to their homes.

Tuki and Huru’s time in Sydney alerted merchants to the flax and Kauri pines growing in their homeland, and soon merchant ships were visiting regularly. Many Māori came back to Sydney on these ships as both visitors and crew, until they were a reasonably regular sight on Sydney’s colonial streets. Paintings of Sydney in the 1810s and 1820s show Māori people amongst the crowds.

In 1805 Māori chief Te Pahi arrived with four sons, spending three months touring Sydney and the surrounding area including Parramatta and John Macarthur’s farms. His daughter Te Atahoe and her ex-convict husband also came to Sydney in 1810, having been kidnapped in New Zealand in 1808 and taken to India before gaining their release. Te Pahi had himself come back to Sydney in 1808 to see Governor Bligh and secure his daughter’s release. She died in Sydney after giving birth and was buried at the Old Sydney Burial Ground.

Relations began to sour after 1809 when a merchant ship, Boyd, was attacked by Māori war canoes in the North Island and all but four people on board massacred. The attack had been prompted by the British captain flogging a Māori chief’s son who was on board the ship.

Although trade and travel continued to flourish, it was done with increasing wariness. By the 1830s increasing incursions by Sydney merchants, missionaries, whalers, timber getters and settlers led to James Busby from Sydney being appointed as Official Resident to represent the British Government in 1832. He was to act as a liaison between the British and Māori. Tensions finally exploded in 1845 in what became known as the Māori Wars. Sydney sent troops and gunboats in the 1840s and again in the 1860s, marking a brutal end to what had been one of the first multi-cultural exchanges outside Australian shores in colonial Sydney.

Read more about New Zealanders and Māori in Sydney on the Dictionary:

New Zealanders by Duncan Waterson

Mark's new book is available now.

Mark's new book is available now.

Dr Mark Dunn is the author of 'The Convict Valley: the bloody struggle on Australia's early frontier' (2020), the former Chair of the NSW Professional Historians Association and former Deputy Chair of the Heritage Council of NSW. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of NSW. You can read more of his work on the Dictionary of Sydney here and follow him on Twitter @markdhistory here. Mark appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Mark!

When a Spade’s a Spade: the hanging of John Hammell

Sydney Gazette, 5 May 1832, p2 via Trove

Sydney Gazette, 5 May 1832, p2 via Trove

On 7 May 1832, John Hammell (also reported as John Hammill, John Haymell and Charles Hammell) was hanged for the murder of his boss George Williamson. Not everyone was sorry Williamson had been bashed in the head with a spade, but committing murder has consequences.

Listen to Rachel and Marlene on 2SER here

The crime unfolded on 18 April at Grose Farm, now the Camperdown site of the University of Sydney. Williamson was the overseer of a work gang at the Farm. The day before he was killed, many members of the gang complained to him that their accommodation was not fit to live in. This was not a minor matter of a routine plumbing issue or a small leak: there was a stream running through the room.

The men were convicts, but they worked hard and believed they were right in requesting different quarters. Williamson, a former convict himself, refused. The Sydney Monitor reported that Hammell, and the other men in his gang, carried on until Williamson instructed Hammell to cut a drain ‘in a peculiar way’.

Hammell did as he was told, but when Williamson found fault with his work and told him he had not made the drain properly, ‘he lifted the spade with which he was working, and struck the deceased on the head, inflicting the wound of which he afterwards died’. The Sydney Monitor also covered the coronial inquiry which revealed that after killing Williamson, Hammell threatened his fellow labourers, but he ‘suffered himself to be secured, and was handed over in custody to some soldiers who came up; the deceased man’s head exhibited two or three cuts, and he expired in less than three hours after the wounds had been inflicted’.

It was shown that the victim was a quarrelsome vindictive tyrant, who would do all that lay in his power to annoy and torment those who offended him; that the place in which the gang slept at night was dilapidated, and admitted the rain in many places; that many of the gang slept on the ground, and, in consequence, on the night previous to the day on which the murder was committed, it being rainy and tempestuous, they were very wet and cold; that the deceased had turned the prisoner, with others of the gang, away from the fire, when drying their clothes, on the morning the murder was committed. The matter went to trial.

Now, in 1832 prisoners were not entitled to counsel. Before 1840, you only had legal representation in New South Wales if you could afford it. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reported that even without anyone acting for his defence, Hammell showed living conditions on the Farm were bad enough that he had ‘begged to be locked up in the cells until the morning’ rather than sleep in the poor accomodation provided. He also said Williamson provoked him by pushing him first.

The judge instructed the jury to, if they believed the prisoner had been assaulted by the deceased, to give a verdict of manslaughter instead of murder. The jury, after taking only fifteen minutes to consider their decision, found Hammell guilty of wilful murder. Justice James Dowling sentenced the prisoner to death.

View of Sydney from Grose's Farm 1819, by Joseph Lycett, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ML 55)

View of Sydney from Grose's Farm 1819, by Joseph Lycett, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ML 55)

The Sydney Herald (now the Sydney Morning Herald) reported Hammell’s execution. For the crime he committed at Grose Farm, he ‘underwent the utmost penalty of the law for his offence, at the usual place of execution’. In 1830s Sydney, the ‘usual place’ for a hanging was the Old Sydney Gaol on George Street, near Sussex Street.

Unfortunately for Hammell, the hanging was not a neat job. After asking spectators to pray for him, he was sent off, but ‘he struggled in strong convulsions for at least five minutes. After hanging the usual time, the body was cut down and sent to the hospital to be dissected and anatomized’.

Highlighting the injustice of the punishment, the Sydney Monitor pointed out: ‘Had the prisoner been rich he would have had a Counsel. That Counsel would have written a defence for him’, and perhaps helped the prisoner better demonstrate ‘that on the present occasion, deceased had been the first aggressor’. A good defence could have also shown that Williamson ‘was a man of a cruel and brutal nature’ and so helped to secure a verdict of manslaughter for Hammell, allowing him to avoid the gallows.

Refs: Defence on Trials for Felony Act 1840 No 32a (NSW) Sydney Herald, 14 May 1832, p.3, accessed 1 May 2021 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12844480; Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 5 May 1832, pp.2–3, accessed 1 May 2021 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2206383; Sydney Monitor, 21 April 1832, p.2, accessed 1 May 2021 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32077427; Sydney Monitor, 12 May 1832, p.2, accessed 1 May 2021 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32077591

Dr Rachel Franks is the Coordinator of Scholarship at the State Library of NSW and a Conjoint Fellow at the University of Newcastle. She holds a PhD in Australian crime fiction and her research on crime fiction, true crime, popular culture and information science has been presented at numerous conferences. An award-winning writer, her work can be found in a wide variety of books, journals and magazines as well as on social media. She's appearing for the Dictionary today in a voluntary capacity. Thank you Rachel!

For more Dictionary of Sydney, listen to the podcast with Rachel & Marlene here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning to hear more stories from the Dictionary of Sydney.

The Hermits of Killarney Heights

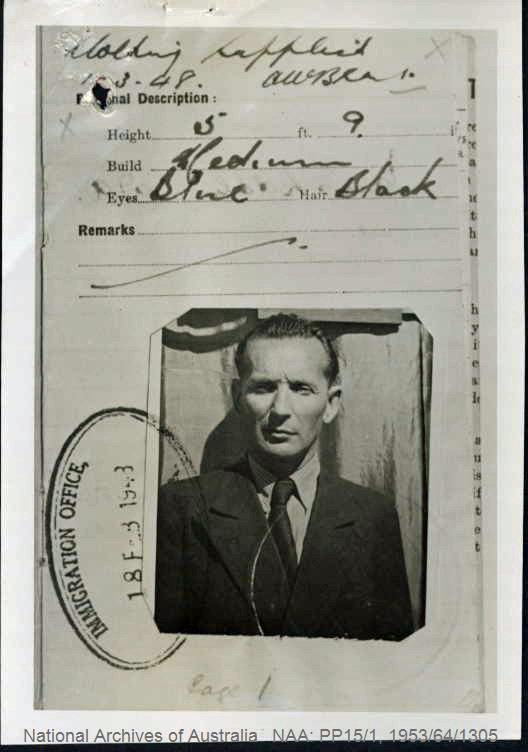

Portrait photo of Stefan Pietroszys attached to Australian Immigration file 1947, National Archives of Australia (PP15/1 1953/64/1305)

Portrait photo of Stefan Pietroszys attached to Australian Immigration file 1947, National Archives of Australia (PP15/1 1953/64/1305)

The picturesque suburb of Killarney Heights at Middlehead was a popular picnic destination named after Killarney in Ireland. However, 41 years ago it became indelibly associated with the suffering of refugees fleeing war torn Europe. Listen to Minna and Wilamina on 2SER here (skip to 135.27)

In 1979, a bearded man emerged from the bushland near Killarney Heights and called out to fishermen in German "Meine Frau ist Tot!" - my wife is dead.

Leading them back to a cave he showed the fishermen his deceased wife lying on foam matting. Confusion erupted about where exactly this couple originated from, speculation ranging from Ukrainian, Russian, Lithuanian to German.

Eventually they were revealed to be Stefan and Genowefa Pietroszys, Lithuanian refugees who had lived in the caves for at least 25 years. Here they had survived on bush rats, berries and hand-outs in the cave, 200 metres from the suburban homes of Killarney Heights. T

he couple were just two individuals of the 2 million migrants that arrived in Australia after the Second World War between 1945 and 1965; part of Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell’s campaign to bring blonde-haired blue-eyed Baltic migrants or ‘Beautiful Balts’ as they became known to Australia.

It was reported that the Pietroszys chose to eke out their existence on the fringes of Middle Harbour because they still lived in fear of the Russian KGB secret police. Perhaps more generally their distrust of authorities was compounded by their traumatic experience of the Second World War. Having witnessed violence at the hands of the Soviets in Lithuania, survived a Nazi labour camp and then an Allied American camp, they arrived in Australia and were then deemed unfit for work and flagged for deportation. Instead, they went on the run through regional Australia for six years.

Portrait photo of Genovefa Pietroszys attached to Australian Immigration file 1947, National Archives of Australia (PP15/1 1953/64/1306)

Portrait photo of Genovefa Pietroszys attached to Australian Immigration file 1947, National Archives of Australia (PP15/1 1953/64/1306)

At Killarney Heights, they did find a compassionate friend in Salvation Army officer Captain Ivan Unicomb, who gained their trust and visited them frequently.

After Genovefa’s death, Stefan wanted to return to the cave but was persuaded to move into a Catholic aged care home at Marayong, where he died in October 1982, aged 84.

Today Stefan and Genovefa lie reunited side-by-side in Frenchs Forest Bushland Cemetery. Their story is a stark reminder of just of the trauma individuals carried with them from what remains the deadliest military conflict in history.

Minna Muhlen-Schulte is a professional historian and Senior Heritage Consultant at GML Heritage. She was the recipient of the Berry Family Fellowship at the State Library of Victoria and has worked on a range of history projects for community organisations, local and state government including the Third Quarantine Cemetery, Woodford Academy and Middle and Georges Head . In 2014, Minna developed a program on the life and work of Clarice Beckett for ABC Radio National’s Hindsight Program and in 2017 produced Crossing Enemy Lines for ABC Radio National’s Earshot Program. You can hear her most recent production, Carving Up the Country, on ABC Radio National's The History Listen here. She’s appearing for the Dictionary today in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Minna!

For more Dictionary of Sydney, listen to the podcast with Minna & Wilamina here at 135.27, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning to hear more stories from the Dictionary of Sydney.

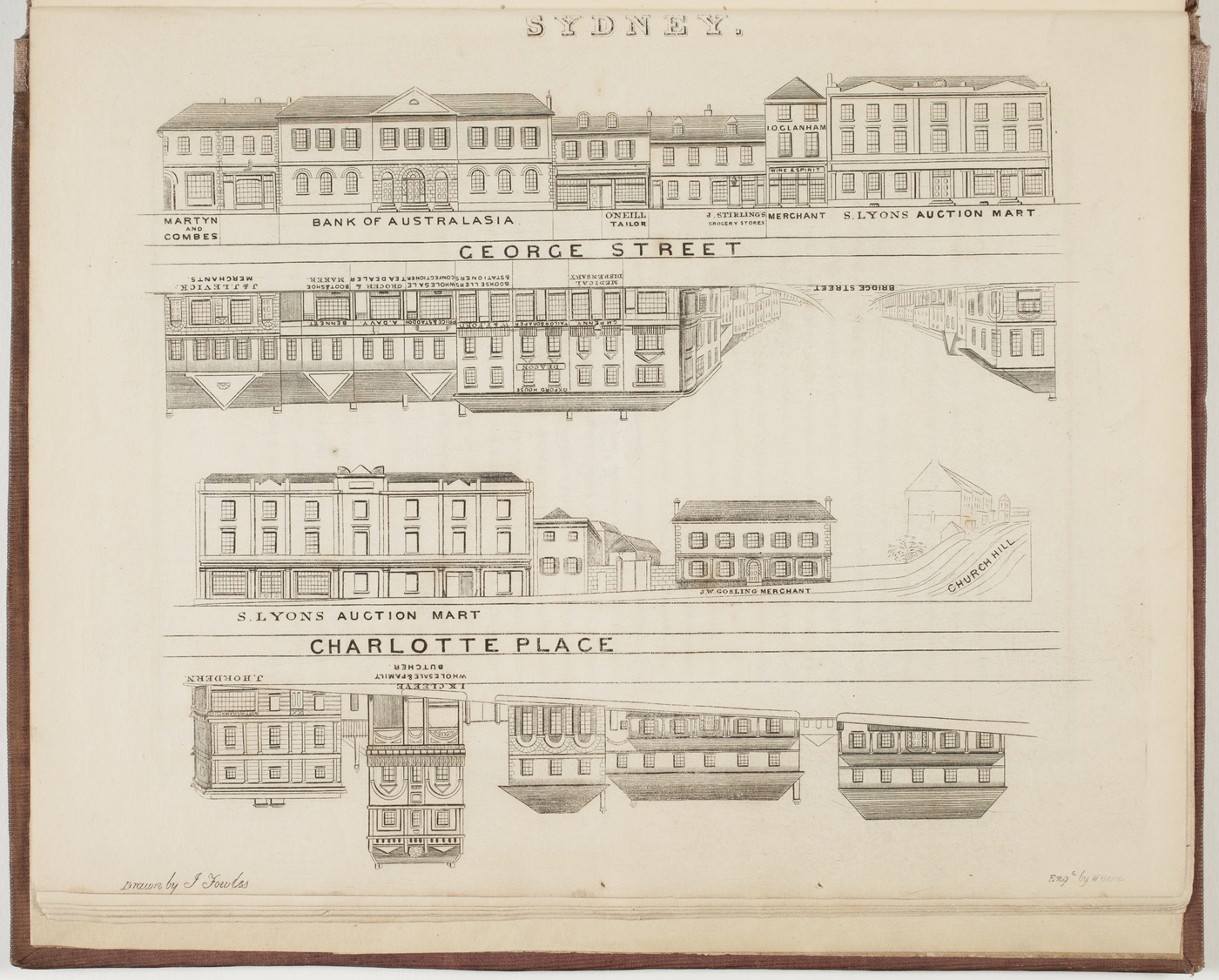

Joseph Fowles

George street and Charlotte Place, in 'Sydney in 1848 : illustrated by copper-plate engravings of its principal streets, public buildings, churches, chapels, etc.' from drawings by Joseph Fowles, Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (DL Q84/56)

George street and Charlotte Place, in 'Sydney in 1848 : illustrated by copper-plate engravings of its principal streets, public buildings, churches, chapels, etc.' from drawings by Joseph Fowles, Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (DL Q84/56)

The Sydney drawing book, c1875, Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales (DL Q85/84)

The Sydney drawing book, c1875, Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales (DL Q85/84)

Brutality at Birch Grove

Headstone of Samuel and Esther Bradley, Devonshire Street Cemetery c1901, Ethel Foster, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ON146/342)

Headstone of Samuel and Esther Bradley, Devonshire Street Cemetery c1901, Ethel Foster, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ON146/342)

Thousands of people travel through Sydney’s Central Station every day, but how many know what once lay beneath it? This nine-part audio series by the State Library of New South Wales will take you on a journey back to 19th century Sydney, to rediscover a place you thought you knew.

Thousands of people travel through Sydney’s Central Station every day, but how many know what once lay beneath it? This nine-part audio series by the State Library of New South Wales will take you on a journey back to 19th century Sydney, to rediscover a place you thought you knew.

Barracluff's Ostrich Farm

Mr Barracluff (Junior) gives Denis a ride, South Head 24 December 1905, Album 36: Photographs of the Allen family, 15 October 1905 - 1 April 1906, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PX*D 578. 1567)

Mr Barracluff (Junior) gives Denis a ride, South Head 24 December 1905, Album 36: Photographs of the Allen family, 15 October 1905 - 1 April 1906, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PX*D 578. 1567)

Barracluff's Ostrich Farm business card c1916, private collection

Barracluff's Ostrich Farm business card c1916, private collection

Auction sale of Barracluff's Ostrich Farm Estate, Rose Bay Heights, December 1917, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Z/SP/W6/161)

Auction sale of Barracluff's Ostrich Farm Estate, Rose Bay Heights, December 1917, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Z/SP/W6/161)

Ostriches on a farm near Sydney c1905, from stereograph private collection

Ostriches on a farm near Sydney c1905, from stereograph private collection

No honour among thieves…

Detail of Convicts embarking for Botany Bay, ca. 1790 by Thomas Rowlandson, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (SV/312)

Detail of Convicts embarking for Botany Bay, ca. 1790 by Thomas Rowlandson, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (SV/312)

Robert Clancy, The Long Enlightenment: Australian Science from its Beginning to the mid-20th Century

Robert Clancy, The Long Enlightenment: Australian Science from its Beginning to the mid-20th Century

Halstead Press and the Royal Societies of Australia, 184 pp., ISBN: 9781925043532, h/bk, AUS$49.99

Robert Clancy, The Long Enlightenment: Australian Science from its Beginning to the mid-20th Century

Halstead Press and the Royal Societies of Australia, 184 pp., ISBN: 9781925043532, h/bk, AUS$49.99

Robert Clancy – who would be familiar to many through his work as a clinical immunologist, gastroenterologist and auto-immune disease specialist as well as his work to promote the study of maps and mapping – set himself an ambitious task to unpack the story of Australian science from colonisation through to the 1950s. The resulting work, The Long Enlightenment: Australian Science from its Beginning to the mid-20th Century, is, predictably, excellent.

This is a history by discipline, rather than by strict chronology, allowing readers to read this book from the first page or to explore different areas of science in which they might have a particular interest. There are sections on botanists, zoologists, agricultural and pastoral scientists, anthropologists, chemists, biomedical scientists, geologists, surveyors, astronomers, physicists and engineers. In all, the contributions of over one hundred innovators are included. There are many names that are well known, including Joseph Banks (botanist), Douglas Mawson (geologist), Thomas Mitchell (surveyor) and John Bradfield (engineer), as well as many names that should be much better known. The Zig Zag Railway, for example, is instantly recognised by most Australians but the man behind the project, John Whitton, is not nearly as famous however as the creatively constructed rail tracks that were built in the 1860s near Lithgow (pp.161, 163).

Each profile offers a neat overview of key biographical information, major achievements and an insight into how the work of one person, or a small team, can contribute to a broader progress. Many of these vignettes cite privilege or being in the right place at the right time. Some also acknowledge a preparedness to invest in those who had obvious potential. Such investment came through the provision of space, resources and, critically, permission to go out and change the world. This book is, perhaps inevitably, dominated by men. Many of these stories might be about ‘permission’, and being granted permission – across the colonial era, into the mid-twentieth century and into the modern day – has always been easier if you are male (more specifically if you are male and you are white). That said, there is an excellent overview of the work of astronomer Ruby Payne-Scott. A career that began in the early 1940s, Payne-Scott helped to research ‘small signal visibility on radar displays and sort out difficulties with noise factors’ to support Australia’s war effort. Later, she would be an integral member of a team that would conduct ‘the southern hemisphere’s first radioastronomy experiment with long wave radiation’ and help identify ‘million degree temperatures in the corona [an aura of plasma that surrounds the sun and other stars]’ (p.148). There is, too, a section on ‘Women in Australian Science’ that discusses some extraordinary achievements made by women, despite concerted efforts to exclude them from the world of scientific work. Clancy notes how women were often restricted to supporting roles, despite obvious intellect and talent, and he offers a shocking statistic to make his point: ‘Through to the 1920s, only one to two per cent of communications in the Journal of the Royal Society (NSW) were authored by women’ (pp.167, 174–75).

The production values are very high, with each section beautifully illustrated by artworks, documents, maps, photographs of objects and of people as well as sketches. The end papers are stunning. Essentially, this is a coffee table book as well as an important resource.

There is an excellent bibliography, one that has been thoughtfully arranged by discipline for those wanting to explore a particular field of science in more detail. There is also a useful index.

Clancy’s history of the long enlightenment in Australia is a narrative of national ambition, of collective enthusiasm and of remarkable (if occasionally difficult) individuals. This volume is an invitation to reflect on our shared scientific past and to engage in science-based conversations about our future. The threat of climate change and the struggle to create a ‘new normal’ in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic are just two of the obvious challenges that face us, in Australia and around the world, right now. I often find myself defending the humanities. Yet, the sciences also face similar issues of public dismissal, political interference and underfunding (pp.8, 175–80). In the opening pages, Clancy asks ‘does it matter?’, do these stories of science matter now? In short, yes, they do. They have to.

Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, March 2021

Visit the State Library of NSW shop on Macquarie Street, or online here.

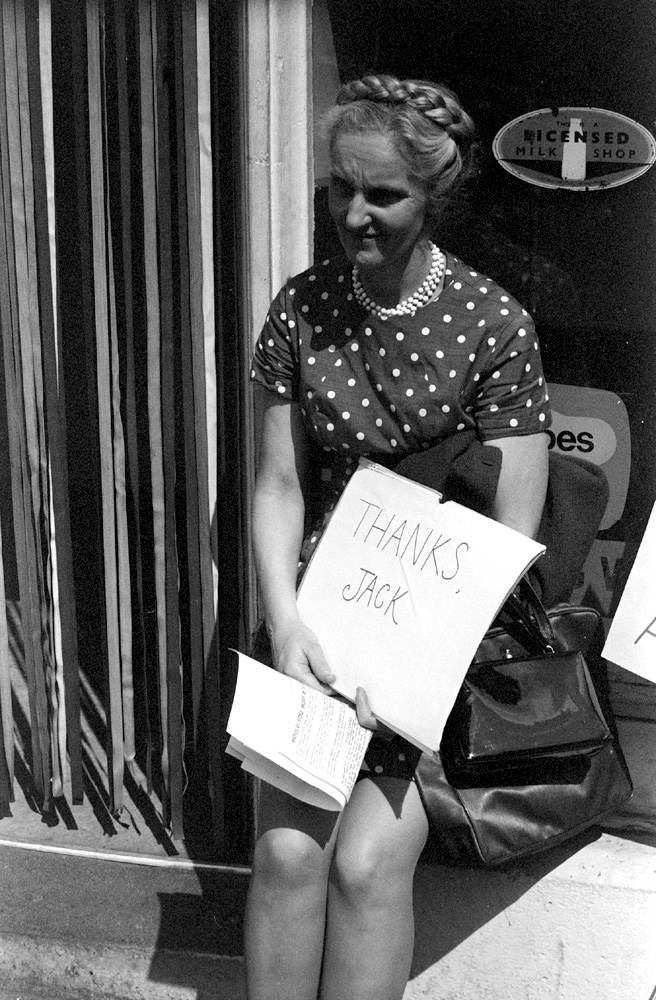

Jack Mundey and the Green Bans

Jack Mundy, Builders Labourers Federation, 1973 by Rennie Ellis © Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive

Jack Mundy, Builders Labourers Federation, 1973 by Rennie Ellis © Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive

- to defend open spaces from various kinds of development;

- to protect existing housing stock from demolition intended to make way for freeways or high-rise development;

- to preserve older-style buildings from replacement by office-blocks or shopping precincts.

'Thanks Jack' Builders Labourers Federation Protest 1973 by Rennie Ellis © Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive

Throw like a girl

Mary Spear and Joy Partridge fielding (England), Betty Snowball wicket keeping, and Hazel Pritchard (NSW) batting during the English women's cricket team tour, Sydney, 1935, National Library of Australia ([PIC/8725/218 LOC Album 1056/C)

Mary Spear and Joy Partridge fielding (England), Betty Snowball wicket keeping, and Hazel Pritchard (NSW) batting during the English women's cricket team tour, Sydney, 1935, National Library of Australia ([PIC/8725/218 LOC Album 1056/C)

Mollie Flaherty bowling 1936, National Museum of Australia (1990.0030.0013)

Mollie Flaherty bowling 1936, National Museum of Australia (1990.0030.0013)

Hazel Pritchard demonstrating the shorts for women adopted by the Australian women's team as their uniform and available as a free pattern in the magazine, Australian Women's Weekly 31 August 1935 p4 via Trove

Hazel Pritchard demonstrating the shorts for women adopted by the Australian women's team as their uniform and available as a free pattern in the magazine, Australian Women's Weekly 31 August 1935 p4 via Trove