The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Green Bans movement

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Green Bans movement

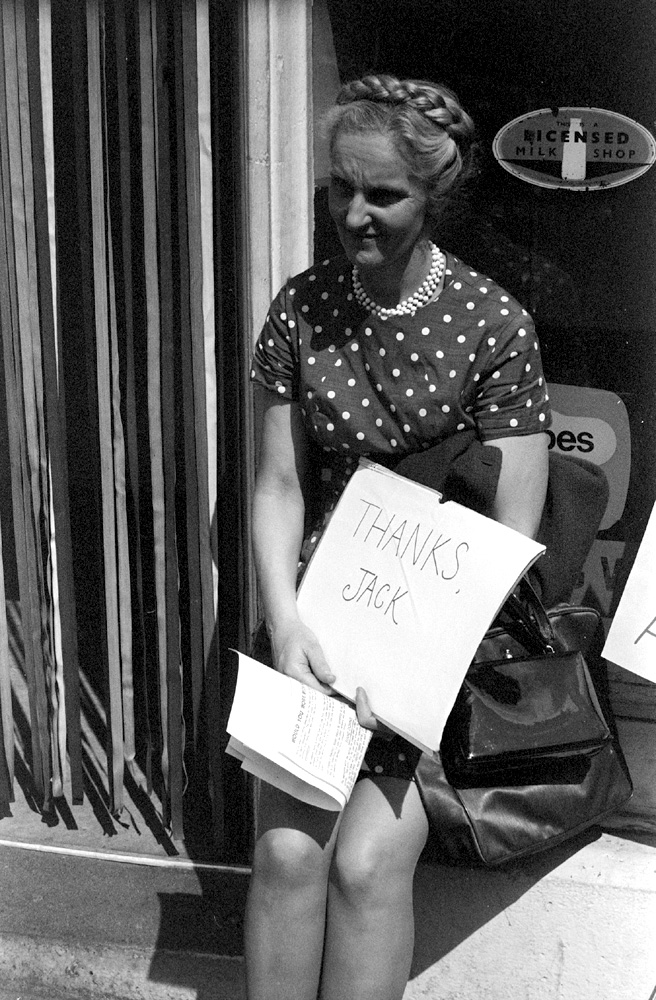

'Green bans' [media]and 'builders labourers' became household terms for Sydneysiders during the 1970s. A remarkable form of environmental activism was initiated by the builders labourers employed to construct the office-block skyscrapers, shopping precincts and luxury apartments that were rapidly encroaching upon green spaces or replacing older-style commercial and residential buildings in Sydney. The builders labourers refused to work on projects that were environmentally or socially undesirable. This green bans movement, as it became known, was the first of its type in the world. [1]

The green bans were of three main kinds: to defend open spaces from various kinds of development; to protect existing housing stock from demolition intended to make way for freeways or high-rise development; and to preserve older-style buildings from replacement by office-blocks or shopping precincts. [2]

Sydney's builders labourers were organised in the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation (NSWBLF). From the mid-1960s, the union had become increasingly concerned with matters of town planning. It persistently criticised the boom in office-block development and predicted an oversupply in office space, long before others became alert to the problem. It pleaded instead for the construction of socially useful projects. [3] By the early 1970s, it had a membership of around 11,000 and covered all unskilled laborers and certain categories of skilled laborers employed on building sites: dog-men, riggers, scaffolders, powder monkeys, hoist drivers and steel fixers.

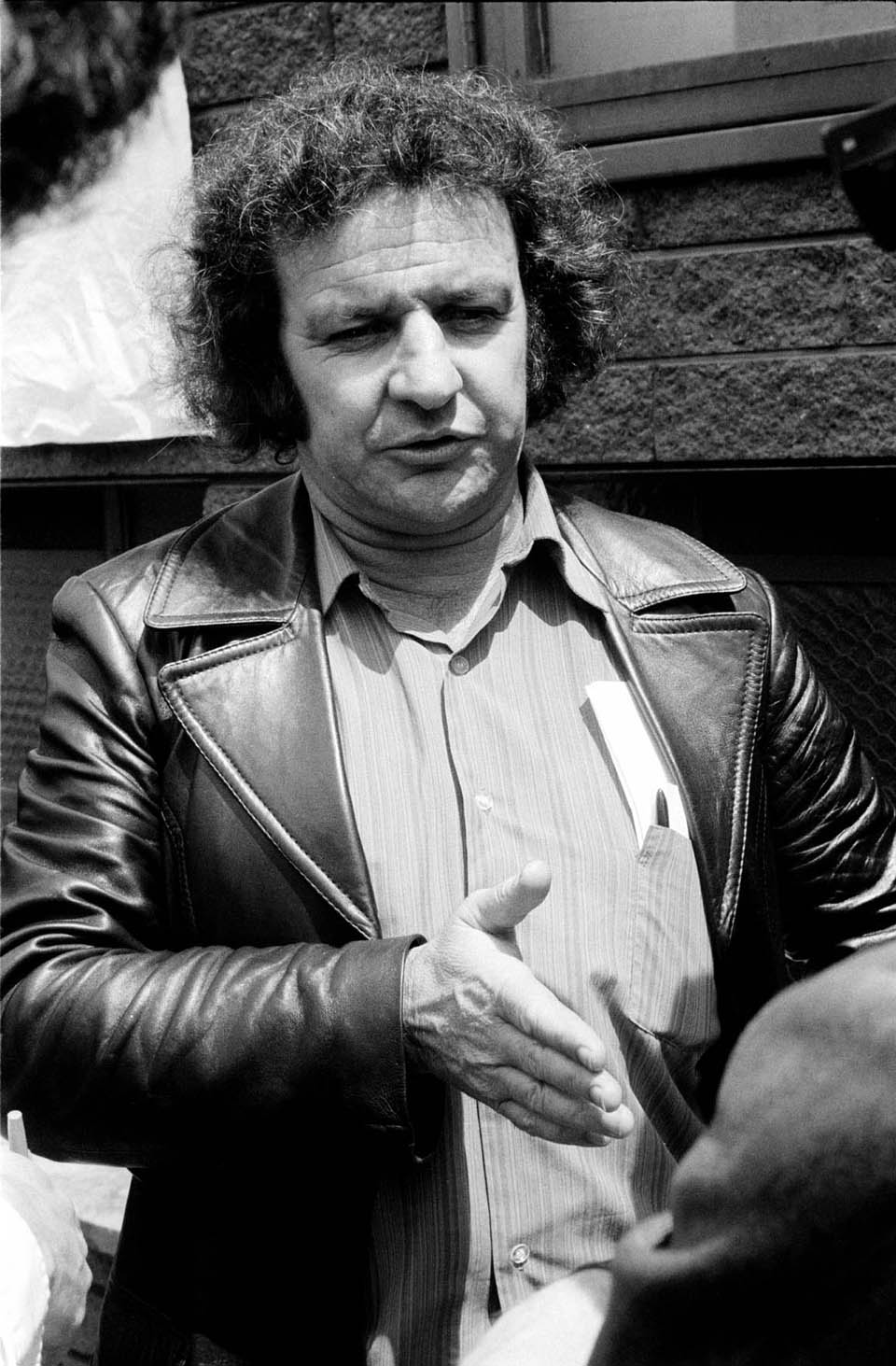

In May 1970, the executive of the NSWBLF resolved to develop a 'new concept of unionism' encompassing the principle of the social responsibility of labor: that workers had a right to insist their labour not be used in harmful ways. [4] It was led by many capable officials but in particular by three outstanding union leaders: Jack Mundey, Joe Owens and Bob Pringle. [5] Mundey and Owens, along with about a hundred of the union's most committed activists, were members of the Communist Party of Australia, which at this stage was subject to New Left influences; Bob Pringle was a member of the Australian Labor Party. Green bans were also imposed by builders labourers in other parts of Australia; but the movement was most spectacular in Sydney, where the construction boom was centred and the union branch most committed to the green bans movement.

In a letter to the Sydney Morning Herald in January 1972, Mundey articulated the union's principles:

Yes, we want to build. However, we prefer to build urgently-required hospitals, schools, other public utilities, high-quality flats, units and houses, provided they are designed with adequate concern for the environment, than to build ugly unimaginative architecturally-bankrupt blocks of concrete and glass offices…Though we want all our members employed, we will not just become robots directed by developer-builders who value the dollar at the expense of the environment. More and more, we are going to determine which buildings we will build …The environmental interests of three million people are at stake and cannot be left to developers and building employers whose main concern is making profit. Progressive unions, like ours, therefore have a very useful social role to play in the citizens' interest, and we intend to play it. [6]

By insisting on a social responsibility for their own labour, the builders labourers presented themselves as protecting the many from the few, and the planet from the profiteers.

Defending the open spaces

In Sydney, the movement got under way in June 1971 when a resident action group from Hunters Hill sought the help of the NSWBLF to save Kelly's Bush on the harbour foreshore, where AV Jennings wanted to build luxury houses. [7] The group of 13 middle-class women, who called themselves the 'Battlers for Kelly's Bush', had already lobbied the local council, the mayor, their State member of parliament and the Premier, all without success. The union asked the women to organise a local meeting to gauge the degree of local support for a ban. More than 600 people turned up and formally requested the union to ban the destruction of Kelly's Bush. When the union agreed to do this, Jennings declared it would use non-union labor. However, building workers on a Jennings project in North Sydney sent this message to Jennings:

If you attempt to build on Kelly's Bush, even if there is the loss of one tree, this half-completed building will remain so forever, as a monument to Kelly's Bush.

Jennings abandoned its plans – so Kelly's Bush remains as an open public reserve. [8] After this first success, resident action groups rushed to ask the NSWBLF to impose similar bans; and the union obliged so long as evidence of widespread local support was provided.

The union worked with environmental organisations, as well as resident action groups, in defence of open spaces. Occasionally professional organisations enlisted the support of the union. For instance, architects and engineers, as well as conservationists, were concerned at the attempt by the state government to locate a carpark for the Opera House underneath the part of the Royal Botanic Gardens poised on the cliff-face overlooking the site. The proposed carpark would interfere with the root system of the ancient fig trees and cause the loss of at least three of them. It also posed a danger to all the nearby vegetation and people's health from exhaust fumes, because the ventilation plans for the underground carpark were inadequate. With government authorities dismissing such concerns, these groups turned to the NSWBLF for support. Accordingly, on 22 March 1972 the union announced that its members would refuse to 'desecrate this area purely for the sake of present-day expediency'. [9] This green ban held firm until saner counsels prevailed. In 1975 the state government announced it would build a carpark beneath the street adjacent to the Botanic Gardens and Opera House. The fig trees were saved.

There were other bans concerned with defence of the natural environment, all of which enabled resident action groups to achieve their objectives. One of these was a ban placed in November 1971 on the construction of extra units on the only park in the middle of the Eastlakes housing estate on the former Rosebery racecourse. With this ban successfully stalling Parkes Development, in mid-1974 an agreement was reached between Botany Council and the developer that the park would remain untouched. Another ban in August 1973 prevented Fowler Ware Industries from turning six acres of forest in West Merrylands into a factory for making vitreous china bathroom items.

For much of 1972, there was a ban on the desecration of Centennial Park and Moore Park to make way for a concrete sports stadium, swimming pool, other sporting facilities and parking lots intended to facilitate a proposed bid by Sydney for the 1988 Olympics. Prominent local resident and Nobel Laureate, Patrick White, was active in this resident action group, and became a great admirer of the green bans movement. During the Centennial Park and Moore Park green ban, Mundey championed the degraded but easily accessible Homebush Bay area as a desirable alternative location, a judgement which was confirmed by the successful upgrading and development of that site for the 2000 Olympics. A large part of Centennial Park was saved from becoming a concrete sports stadium. [10]

Saving the built environment

[media]An important aspect of the green bans movement was the emphasis on preserving working-class residential areas from attempts by developers to cater for a more lucrative market. Mundey argued that ordinary people were being driven out of inner-city areas because of the government's lack of courage to tackle the 'sole right' of the developer. He insisted governments and municipal authorities should face up to their responsibility of ensuring that urban dwellers paid reasonable amounts of rent for decent housing. The NSWBLF, he promised, would use its green bans always 'in support of those most urgently in need of quality housing'. [11]

One of the most significant urban areas saved was The Rocks, site of the first European settlement on Sydney Harbour in 1788. From November 1971 until 1975, the NSWBLF green ban saved the oldest buildings in Australia and attractive foreshore parks from demolition to make way for glass and concrete office blocks. The union was concerned not merely about the threat to the historic buildings of the area but also the invidious treatment meted out to the low-income residents: the cleaners, sailors, wharfies, pensioners, shop assistants and others who lived in this traditionally working-class neighbourhood. It halted the redevelopment project 'because the scheme destroys the character of this historic area and ignores the position of the people affected'. The Rocks Resident Action Group mobilised enthusiastically in support of the ban and drew up a 'people's plan' for acceptable renovation of the area. It announced that, in the face of the usual apathy, inaction and favoritism of the government, it had been left to unionists 'to show leadership in protecting our citizens and their historic buildings'.

With the green ban prompting the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority to propose a series of improved plans, the union position was stated clearly by Mundey in August 1973: 'My federation will lift its ban when the residents are satisfied with what is being put forward by the authority'. In March 1974, when the latest plan was again sent back to the architect, a reporter observed: 'the most powerful town planning agency operating within NSW at the moment is the BLF.' When the next set of plans eliminated high-rise buildings in conformity with the 'people's plan', the ban was lifted. By the 1990s, the Ministry for Planning admitted that the green ban had resulted in the plans for the area being 'an overwhelming success', reflected in the millions of tourists who visit the historic area each year. [12]

Another working-class area saved was Woolloomooloo, home to maritime workers and fishermen, which would have been turned into high-rise office blocks, skyscraper hotels and parking lots. Thanks to a green ban placed in February 1973 on the entire suburb and not lifted until early 1975, 65 per cent of the area was retained by the Housing Commission for low-income earners, under a plan that entailed a genuine socio-economic mix of residents living in medium-density buildings with many trees and landscaped surroundings.

Some developers were prepared to use brute force to evict poorer tenants. In one instance the green ban movement came into serious conflict with the criminal underworld of Sydney, during the ban to preserve the attractive working-class residences and streetscape of Victoria Street, Kings Cross, from redevelopment geared to a much higher-income residential market. Despite National Trust attempts to persuade Sydney City Council to preserve these residences, from the late 1960s most of Victoria Street was being bought by developers, such as Frank Theeman whose links with criminal elements are well documented. [13] The NSWBLF placed a green ban on Victoria Street in April 1973. However, armed thugs vandalised Theeman-owned buildings earmarked for demolition and terrorised the residents; one green ban activist disappeared and returned too frightened to say what had happened to him; and another – Juanita Nielsen – disappeared on 4 July 1975. Her body has never been found. [14] Resident activists who had defended the buildings during much of 1973 by squatting in them were forcibly evicted by police on 3 January 1974. The ban was lifted late in 1974 after 'Intervention' (see below). Although the green ban successfully prevented hideous high-rise development and saved much of the attractive streetscape, which rapidly became gentrified, the lifting of the green ban meant that the area did not retain a significant proportion of low-income housing stock, as intended in the placing of the ban.

These bans on these inner-city working-class residential areas ensured that local residents' aspirations for their communities, expressed in the community plans drawn up for The Rocks, Woolloomooloo, Darlinghurst and Kings Cross, to replace the plans of developers stalled by green bans, were largely realised. [15] Many other inner-city working-class residential areas, two-thirds of whose adult residents did not own cars, were rescued from being flattened by new freeway projects. These areas included Ultimo, Pyrmont, Glebe, Annandale, Rozelle and Leichhardt, which were threatened by the North-western Expressway; and Darlinghurst and Woolloomooloo, which were threatened by the Eastern Expressway. The NSWBLF officials consistently opposed relentless freeway construction and the consequent diversion of resources and funding away from public transport. [16]

In one case the NSWBLF not only defended the rights of the urban poor but brought about the first successful Aboriginal land rights claim in Australia. In December 1972 the union placed a ban on the demolition of 'empty' houses occupied by Indigenous Australians in Redfern. A big developer, IBK, had bought the houses to renovate as expensive townhouses and had evicted the Aborigines. Stalling the project allowed sufficient time for the newly elected federal Labor Government to buy the disputed houses from the developer and grant the area to the black community in March 1973, as an Aboriginal housing scheme under Aboriginal control. This Redfern Aboriginal Community Housing Scheme, comprising 65 houses, provided much-needed low-rental accommodation; and vacant factories in the area were transformed into various facilities, such as a preschool, a medical centre and a cooperative shop, with the whole project managed by an elected cooperative committee. [17]

Several green bans were placed in support of urban resident action groups resisting smaller-scale high-rise residential developments. These bans – in Waterloo, Earlwood, Cook Road near Centennial Park, Bankstown, Manly, Mascot, Matraville and South Sydney – prompted what was termed the 'high-rise low-rise battle' in the letters columns of newspapers. Joining the fray, a letter from Mundey called on governments and municipal authorities to prevent the tendency of developers to go 'up and up'. [18] With public housing authorities imitating this tendency, the adverse personal effects of 'suicide towers' were starting to agitate town planners, social workers and sociologists. The ensuing retreat from high-rise public housing was encouraged by green bans on high-rise apartment blocks. Visiting as a guest of the state Housing Commission, anthropologist Margaret Mead applauded the green bans movement for its resistance to high-rise housing. She stated: 'I'm very impressed that they have taken up the cause of humanity.' [19]

Preserving heritage

Heritage sites, like domestic housing, were also at risk from the operations of developers. The National Trust turned to the NSWBLF to aid its efforts to save sites of architectural and cultural significance from replacement by high-rise office blocks and freeways. The NSWBLF announced on 19 January 1972 that it would refuse to demolish any of the 1700 buildings in New South Wales recommended for preservation by the National Trust:

Anyone with a conscience has to speak up—the building industry has gone mad .... we don't want the next generation to condemn us for slapping up the slums of tomorrow. [20]

Mundey commented in January 1973 that if governments enacted laws so owners of historic buildings could be compensated and these buildings retained for posterity,

it will not be necessary for the Builders Labourers' Federation to be the conscience of Sydney, and we can join those civilised countries which do appreciate their history and the need for retention of some of the best of our past.

In the meantime, and in the absence of such legislation, 'our union will continue to ... give teeth to the National Trust's list of buildings worthy of preservation, by our refusal to demolish such buildings'. [21]

Heritage buildings saved by green bans included: the Pitt Street Congregational Church (February 1972); the Theatre Royal (May 1972); the Regent Theatre (October 1972); the Newcastle Hotel in George Street (October 1972); the Helen Keller Hostel for Blind Women in Waimea Avenue, Woollahra (March 1973); the Royal Australasian College of Physicians, an 1848 building at 145 Macquarie Street (December 1973); the Catholic Church Presbytery, an Edwardian mansion in Moore Park Road (May 1974); and the State Theatre (June 1974).

The terminology of 'green ban'

For such significant new actions, a new phrase was needed. Because these bans were not imposed in the economic interests of the workers concerned, the usual terminology of 'black ban' seemed inappropriate; the workers were even enduring negative financial consequences in lost wages over the imposition of bans. In February 1973, more than 18 months after the movement had started, Mundey coined the term 'green ban' to distinguish it from the traditional union black ban imposed by workers 'to push their own issues'. Mundey argued that the term was 'more applicable as they are in defense of the environment'. He explained his new usage:

It was considered that 'green' instead of 'black' was more truly descriptive of this form of environmental activity because the imposition of a 'green ban' had much more positive social and political implication than the more defensive connotation often associated in the public mind, with 'black bans'. [22]

Green bans, unlike black bans, contained both an environmental element and a social element: they expressed the union's determination to save open space or valued buildings and to ensure that people in any community had some say in changes that affected their lives. [23]

By mid-1973, the term 'green ban' was being used regularly to describe the union's actions. [24] Indeed, at this time, press use of the term 'greenies' designated supporters of the NSWBLF green bans, [25] from which point it later broadened to embrace environmentally concerned people in general. Speaking in parliament on 21 March 1997, Senator Bob Brown of the Australian Greens explains how this happened:

Petra Kelly, the feisty, intelligent, indefatigable German Green, came to Australia in the mid-1970s. She saw the green bans which the unions, not least Jack Mundey, were then imposing on untoward developments in Sydney at the behest of a whole range of citizens who were being ignored by parliaments. Thank glory that, because of their action in the mid-1970s, such places as the Rocks, one of the most attractive parts of Sydney, still exist. She took back with her to Germany this idea of Greens' bans, or the terminology. As best we can track it down, that is where the word 'green' as applied to the emerging Greens in Europe came from. [26]

Kelly did not simply import Sydney vocabulary into Germany but was so inspired by the green bans movement that it was mainly responsible for her launching the German Green Party; she would often speak about the impact the green bans had upon her and her philosophy and that she was especially impressed with the linkage achieved between environmentalists and a progressive trade union movement. [27]

Resident action groups

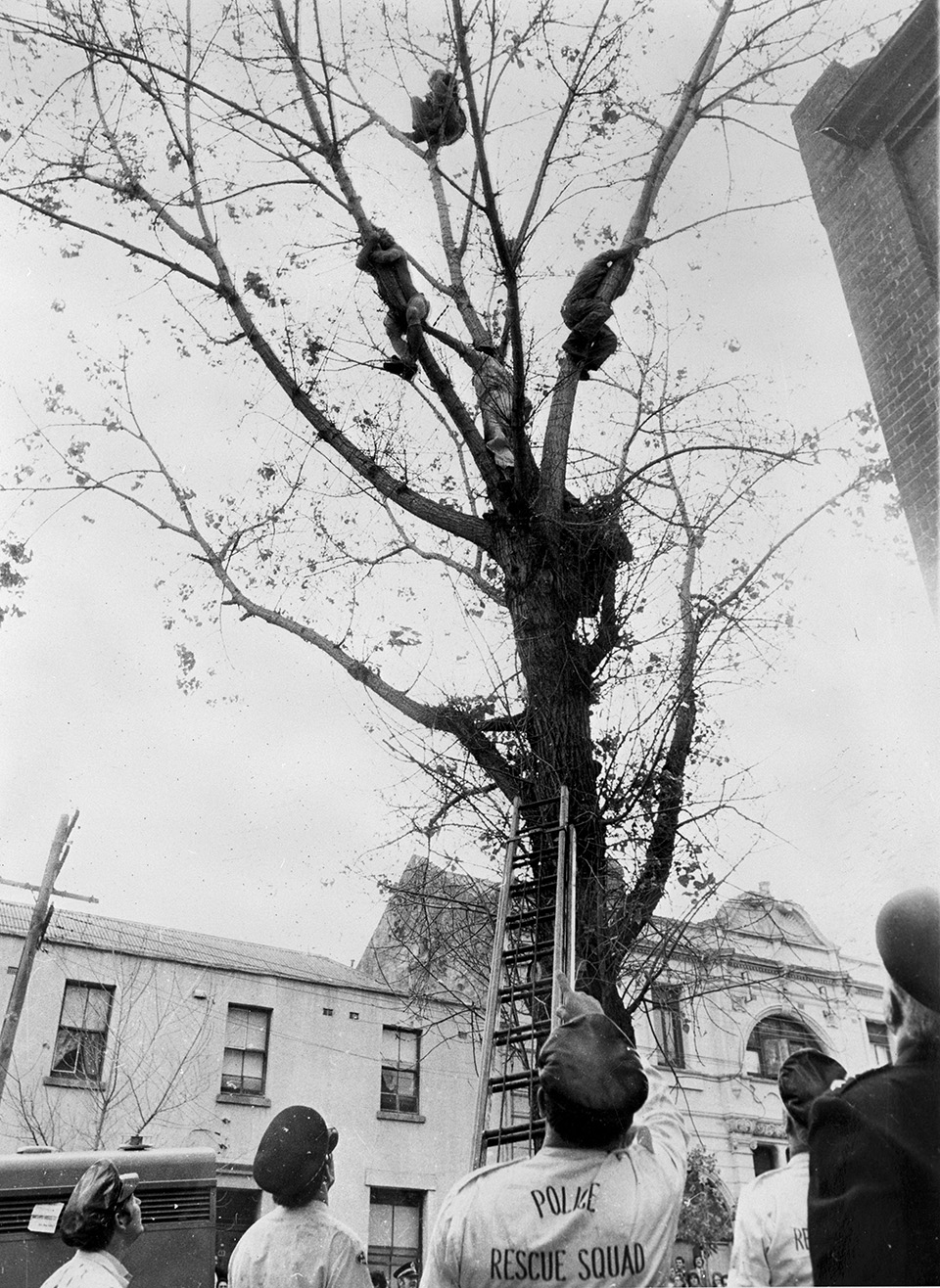

[media]On the ground, the union's green bans were supported keenly by resident action groups, generally more representative of community sentiments than the local councils, which almost invariably favored the land development interests that, for a range of historical reasons, had always been over-represented at local government level. Resident action groups mushroomed throughout Sydney from mid-1971, once the green bans were under way. By 1974, there were about one hundred such groups operating in the greater metropolitan area, and the formation in 1972 of the Coalition of Resident Action Groups (CRAG) – an umbrella organisation – enabled these groups to pool resources and coordinate their efforts.

The NSWBLF green bans encouraged the spread and growth of resident action groups at this time, because the bans both publicised environmental problems and, more significantly, offered a palpable chance of success in confronting such problems. CRAG convener Murray Geddes commented: 'The BLF were exactly what we (the residents) needed.' [28] The union's very real power at the point of production was enhanced even further by an aura of power; each green ban victory helped ensure the next. Mundey and the other NSWBLF ideologues also possessed an important agitational attribute: they were never dull. The green ban campaigns, which included posters, pamphlets, graffiti, balloons, sit-ins, picnics, demonstrations, Green Ban balls, crane occupations, dressing up as high society guests and gate-crashing a developer's party, and a host of other imaginative tactics, displayed inventiveness, humor and vigour. The NSWBLF became the hub of radical activity in Sydney, and increasingly so as it widened its scope to include issues of concern to women, prisoners, Aborigines and homosexuals. For the union's supporters in the wider public, it became not only a rallying point but also a symbol of working-class radical potential.

In the resident action groups in particular, green bans mobilised people previously untouched by radical politics, and won many sympathisers among people not normally well-disposed towards unions. Mundey believed that action against the developers and the conservative state government would radicalise residents from middle-class areas – and in most cases he was correct, for the ideas articulated so effectively in the green bans movement attracted people distant from any kind of left-wing milieu to embrace radical causes, and to draw connections between their particular experience and wider social problems. Resident action groups broadened their focus beyond particularistic concerns and became involved in other social issues that grew naturally out of the greatly radicalised resident activism of the green bans movement, issues such as low-cost housing, public transport, tenants' rights, and even prisoners' rights and urban Aboriginal land rights. [29]

The metaphors used to describe the relationship between the NSWBLF and resident action groups or organisations such as the National Trust were revealing. Typically, the union was described as providing the 'muscle'; or the Trust and resident groups lacked the 'teeth' that the union had. [30] The federal Department of Urban and Regional Development in 1973 acknowledged the effectiveness of the NSWBLF:

Where pleas and reasonable requests could be ignored or summarily dismissed by government, and especially by private developers, the threat of direct strike action by workmen on the site is a matter of immediate concern and negotiation. [31]

Impact and outcomes

In New South Wales in total, more than 40 green bans were imposed, predominantly in Sydney. About half of these prevented the destruction of individual buildings or green areas; the other half thwarted development projects affecting larger areas. By October 1973, these bans had halted projects worth 'easily $3,000 million', according to the Master Builders Association. [32] By 1975 bans had stalled $5,000 million of development at mid-1970s prices, saving Sydney from much of the cultural and environmental destruction it would otherwise have suffered. [33]

Over and above the preservation of specific sites, green bans had a significant impact on environmental legislation, town planning and public attitudes. At both state and federal level, governments initiated or improved legislation to ensure more socially responsive and ecologically responsible planning and development. [34] On 1 March 1974, the Australian Financial Review described such laws and regulations as

an obvious reaction … to the rising power base being cemented by the increasing number of resident action groups … following their alliance with the BLF which has become their muscle arm in imposing green bans.

The green bans movement also transformed the culture of urban planning to show greater sensitivity to environmental and social concerns, instill a better appreciation of heritage, and to recognise the need to publicise proposed developments well in advance and seek approval from the people affected. [35]

These changes were fortunate, because the green bans movement collapsed when developers became so frustrated by this particular display of union power that they bribed other unionists – corrupt ones – to break the bans. As a result, late in 1974 the federal officials of the BLF arrived in Sydney, declaring that the New South Wales branch had 'gone too far on green bans'. Known as 'Intervention', this move on the part of the Melbourne-based federal body was inspired partly by sectarian animosity – the Federal Secretary, Norm Gallagher, was prominent in the China-line Communist Party of Australia (Marxist-Leninist). More significantly, 'Intervention' was funded by developers desperate to break the green bans. Despite protests and impressive displays of support for the green bans movement, over the next six months the federal union and employers worked together to ensure that only builders labourers with new 'federal' union tickets were employed in the industry and those with 'State' tickets were denied a living. Work recommenced on sites that had been subject to green bans. The Australian Conservation Foundation expressed its disappointment at the lifting of the green bans, which had been such 'a major, effective weapon'. [36]

References

Meredith Burgmann and Verity Burgmann, Green bans, red union: environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers' Federation, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998

Jack Mundey, Green bans & beyond, Angus & Robertson, London and Sydney, 1981

Notes

[1] Michael Allaby, (ed), Macmillan Dictionary of the Environment, 2nd edition, Macmillan, London, 1983, p 234

[2] Meredith Burgmann and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union. Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers' Federation, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998, pp 167–299

[3] Builders Labourer, July/August 1966, p 9; Builders Labourer, September/October 1966, p 1; Builders Labourer, April/May 1967, pp 3, 11; NSWBLF Minutes, Delegates' Conference, 18 June 1967, p 3; NSWBLF, Federal Conference Agenda Items, 1968, NSW Item (8) Housing

[4] NSWBLF Minutes, Executive Meeting, 12 May 1970

[5] For a study of Jack Mundey, see Verity Burgmann and Meredith Burgmann, '"A rare shift in public thinking": Jack Mundey and the New South Wales Builders Labourers' Federation,' Labour History 77, November 1999, pp 44–63

[6] Quoted in Pete Thomas, Taming the Concrete Jungle: The Builders Laborers' Story, Australian Builders Labourers Federation, Sydney, 1973, pp 56–7

[7] The first green ban was imposed by the Victorian BLF branch in October 1970, when it prevented a developer from destroying a park in Carlton in inner Melbourne. However, Kelly's Bush is significant as the first ban in Sydney where the movement was strongest

[8] Jack Mundey, 'Preventing the Plunder,' in Verity Burgmann and Jenny Lee (eds), Staining the Wattle, McPhee Gribble/Penguin, Melbourne, 1988, p 177. For details of the Kelly's Bush green ban, see Meredith Burgmann and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union. Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers' Federation, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998, pp 6, 46–47, 169–78, 196, 250, 260, 277, 284

[9] Australian, 22 March 1972; Sydney Morning Herald, 22 March 1972; Daily Telegraph, 23 March 1972; Sun-Herald, 26 March 1972; Review, 9 April 1972; Richard Roddewig, Green Bans: The Birth of Australian Environmental Politics, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1978, p 29

[10] Meredith Burgmann and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union. Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers' Federation, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998, pp 178–193

[11] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 August 1973

[12] Meredith Burgmann and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union. Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers' Federation, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998, pp 195–201

[13] Sydney Morning Herald, 3 March 1998

[14] Australian Financial Review, 4 May 1973; Sydney Morning Herald, 5 May 1973; 'Victoria Street. History', Scrounge, 1, p 5

[15] National Times, 2 June 1978; Bob Carr, 'Now the ban's on Mundey,' Bulletin, February 24, 1981, pp 39–40; Marion Hardman and Peter Manning, Green Bans: The Story of an Australian Phenomenon, Australian Conservation Foundation, Melbourne, undated [1974–75]1976; Jack Mundey, Green Bans and Beyond, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1981, p 91; Jack Mundey, 'Preventing the Plunder,' in Verity Burgmann and Jenny Lee (eds), Staining the Wattle, McPhee Gribble/Penguin, Melbourne, 1988, p 178; John Yeomans, 'A grand plan founders on the Rocks', Melbourne Herald, 26 March 1974; Grace Karskens, The Rocks: Life in Early Sydney, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1997, p 5; Richard Roddewig, Green Bans: The Birth of Australian Environmental Politics, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1978, pp 16–28; Max Kelly, Anchored in a Small Cove, A History and Archaeology of The Rocks, Sydney, Sydney Cove Authority, Sydney, 1996, pp 107–110; Newcastle Morning Herald, 22 February 1974

[16] Meredith Burgmann and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union. Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers' Federation, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998, pp 201–227

[17] Daily Mirror, 21 March 1973; Builders Labourer, 1973, pp 33–35

[18] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 August 1973

[19] Sydney Morning Herald, 9 November 1973

[20] Australian, 20 January 1972

[21] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 January 1973

[22] Ann Turner, (ed), Union Power: Jack Mundey v George Polites, Heinemann Educational, Melbourne, 1975, p 22

[23] Jack Mundey, Green Bans and Beyond, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1981, p 105

[24] Advertisement, Australian, 26 October 1973, authorised by Director, Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority; Advertisement, Daily Telegraph, 1 November 1973, authorised by J Martin, Master Builders' Association

[25] Age, 1 November 1973

[26] Parliamentary Debates, Senate, 21 March 1997

[27] Bob Brown & Peter Singer, The Green, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1996, pp 64–5

[28] Murray Geddes, interviewed by Meredith Burgmann, 23 January 1981

[29] For examples, see Inner Core of Sydney RAGS, Low Cost Housing, 1973; Save Public Transport Committee, The Commuter (produced by concerned unionists, residents, students and commuters); The Rapier (produced by the concerned residents of the inner city of Sydney), undated [late 1973]; Robert W Bellear, (ed), Black Housing Book, Sydney, 1976; Foundation Day Tharunka, 2 August 1973

[30] Meredith Burgmann and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union. Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers' Federation, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998, pp 210, 277

[31] Daily Telegraph, 14 November 1973

[32] Sun, 26 October 1973; 8 November 1973

[33] Tim Bonyhady, Places Worth Keeping. Conservationists, politics and law, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1993, p 39; Mark Haskell, 'Green Bans: Worker Control and the Urban Environment,' Industrial Relations, 16 (2), 1977, pp 206, 212, 214

[34] Australian Financial Review, 1 March 1974; Richard Roddewig, Green Bans: The Birth of Australian Environmental Politics, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1978, pp 79–83; Andrew Jakubowicz, 'The green ban movement: urban struggle and class politics,' in J Halligan and C Paris (eds), Australian Urban Politics: Critical Perspectives, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne, 1984, p 162; National Times, 1 July 1978, p 33; Ann Summers et al, The Little Green Book: The Facts on Green Bans, Ruth & Shelton, Sydney, 1973, p 15; Bob Carr, 'Now the ban's on Mundey,' Bulletin, February 24, 1981, p 40

[35] PN Troy, Head of Urban Research Unit, Australian National University, interviewed by Verity Burgmann, 21 November 1997

[36] ACF, 'News Release,' 2 November 1974. For details of Intervention, see Meredith Burgmann and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union. Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers' Federation, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998, pp 267–275

.