The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Treating Sydney's sick

Detail showing the Sydney Infirmary from 'Bird's eye view of Sydney Harbour' by FC Terry, c 1856 courtesy National Library of Australia ( PIC Drawer 2407 #S1997)

Detail showing the Sydney Infirmary from 'Bird's eye view of Sydney Harbour' by FC Terry, c 1856 courtesy National Library of Australia ( PIC Drawer 2407 #S1997)

You can listen to their entertaining and informative conversation here:

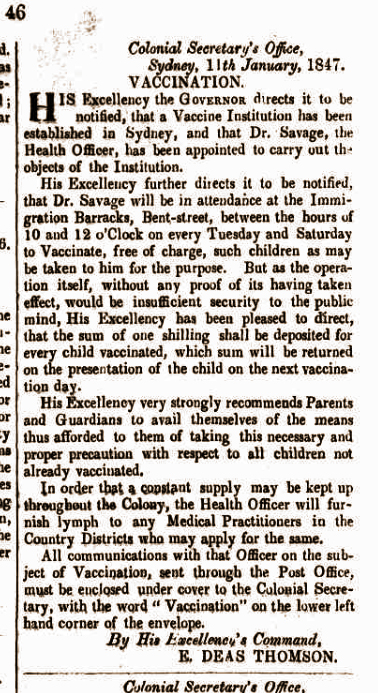

Until the late 1830s, hospitals in Sydney were provided by the government only for convicts, who they saw as a source of free labour, and government personnel like the military, employed to supervise the convicts and maintain the security of colony. This wasn't unreasonable in terms of what people thought about healthcare and hospitals at the time. If you were sick, you called in a doctor to visit you at home, or relied on family and friends for care, or you might make use of herbal and traditional remedies. If you were poor or indigent, you were dependent on the small number of charitable institutions who might be able to take you in. Hospitals were more like a convalescent home or hospice for the dying than we think of them today. Even into the 1870s, hospitals were still not places one would attend in anticipation of a full and rapid cure. If you were sick in the 19th century, the hospital was an option of last resort. New South Wales Government Gazette 12 January 1847, p46 via Trove

New South Wales Government Gazette 12 January 1847, p46 via Trove

A bed in the Infirmary was by no means a given, even by the 1860s. Sydney Punch, 4 September 1869, p128

A bed in the Infirmary was by no means a given, even by the 1860s. Sydney Punch, 4 September 1869, p128

Categories

Blog

2ser

health

hospitals

immunisation

immunity

infectious diseases

medical history

medicine

Nic Healey

Peter Hobbins

public health

smallpox

sydney history

Sydney hospital

Sydney Infirmary

vaccination

vaccine institution

vaccines