The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Children's institutions in nineteenth-century Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Children's institutions in nineteenth-century Sydney

In the 1790s in the struggling colony of New South Wales, some concern was expressed in Sydney Town about the growing number of neglected or destitute children living rough in the streets without visible support beyond their own efforts in dealing with the world. These sightings could have sometimes been misinterpreted by the observer: children were simply playing in the streets and then returning to their parents at nightfall. A child social welfare concern, nevertheless, had been identified, involving the offspring of convict women and marines, soldiers, sailors and convict men. The Reverend Richard Johnson, an earnest evangelical and the colony's first chaplain, was convinced that the situation was serious and could endanger the moral state of the colony. To him, a serious threat was poised to the future of the rising generations. [1]

Johnson was already considering a plan to found a residential orphanage in Sydney to clear the streets of abandoned children by converting the first temporary church into such an establishment as soon as a permanent building could be built for public worship. His plans were thwarted in 1799 when the wooden building was burnt down by 'some evil-minded person or persons'. [2]

Despite this setback, Johnson was able to gain the ear of the colony's new Governor, Philip Gidley King, who had already established an orphanage on Norfolk Island for female convict children when he was Lieutenant Governor there between 1788 and 1796. King maintained a strong interest in Norfolk's Female Orphan House. Of the 163 children on Norfolk Island in 1796, 64 were supported by their parents and 99 were victualled from government stores. [3] This proportion indicates that the problem of neglected children was real enough and, given the turbulent times, could well be of similar proportions in Sydney Town.

Samuel Marsden in Sydney

A practical solution needed to be reached. The Reverend Samuel Marsden, second colonial chaplain and another staunch and even fiercer evangelical, claimed that some children were already being boarded out with other mixed convict families. He did not view boarding-out as a good solution, because of the convict taint. He wrote a letter to William Wilberforce, the evangelical parliamentarian in England, declaring that the local boarding-out solution for neglected children was wasting scarce resources by the extravagant provision of extra rations to undeserving convict families. A public building for the reception of such children was by far a better economical solution. As a critical mass gathered together, they could be resourced much more cheaply by the State. To Marsden, such an institution would ensure that destitute and neglected children would be 'brought up in the principles of morality and industry'. He went on to underline the urgency with a melodramatic hyperbole: 'If some private or public establishment is not instituted for them, they will be more abandoned than their unfortunate parents; at present they are brought up in idleness and uncleanness, and robbery, and scattered up and down in every part of the settlement'. [4] To Marsden, they were a social menace.

His views hit on the main themes embodied in the child welfare movement of nineteenth-century Sydney – the incarceration of children for the course of their natural childhood in institutions, and the partnership between private and government philanthropy. Sweeping children from the mean streets into institutions in Sydney and Parramatta became an obsession both with government officials and philanthropic citizens. From the 1820s, Sydney became the hub of child-rescue institutions until the last decade of the nineteenth century. Governments and philanthropists in Sydney worked together to formulate policies for and impositions upon vulnerable lower-class children. They claimed concern about the child's soul, but were also considering the future manpower needs of the State. Both these concerns continued, but Marsden implied strongly that it was to be joined by another one, 'a concern to save children from the enjoyment of childhood', [5] since he saw them not as innocents but as original sinners. By placing them in a sternly regulated asylum that removed enjoyment, habits of industry and morality drawn from rigid religious ideologies would be inculcated.

The Female Orphan School

The [media]situation for girls was viewed as the most urgent. Governor King briefly outlined its curriculum: the 'children are [to be] taught needlework, reading, spinning and some few writing'. The emphasis on domestic training was supposed to bring into effect King's prime object of moral regeneration by rescuing girls from the 'great depravity' which existed among the 'present inhabitants' of the colony. [6]

The Female Orphan School soon became popularly known as Mrs King's Orphanage, as the governor's wife became absorbed in its management. Governor King frequently referred to the Female Orphan School in his official dispatches. By May 1803, there were 103 inmates who had been picked up from the streets. Thus, according to King, their entrapment in an institution would greatly benefit the morals and manners of the present Sydney inhabitants. [7] Their future destiny was to be as industrious domestic servants or dutiful wives of colonists. They were to help remove the convict stain on the settled community.

King decided that destitute street boys would benefit by a system of apprenticeship:

To lessen the evil as much as possible the convict boys that arrive (of which I am sorry to say there are a great number) are put on as apprentices to the boat builders and carpenters and several have made themselves very useful. [8]

Boys were treated differently to girls at first, forced into the workforce and bonded to an apprenticeship, while girls were placed in a protective enclosure. Marsden made his ideology clear:

Remote, helpless, distressed and young, these are children of the State and though at present very low in the ranks of society, their future numerous progeny, if care is not taken of the parent stock, may by their preponderance over balance and root out the vile depravities bequeath'd by their vicious progenitors. Their numbers will in a very few years increase beyond that of the then existing convicts and what the character of this rising race shall be is therefore an extremely interesting thing. [9]

With consideration of the alarm he felt about 1025 illegitimate children in the colonial child population of 1832, Marsden saw the necessity of state intervention into the lives of the children of the impoverished classes, thus upholding the notion of 'Mother State and Her Little Ones', an ideology of social control. Antonio Gramsci, the twentieth-century Italian social theorist, saw such a notion in terms of hegemony, 'a movement' in which the philosophy and practice of a society fuse and are in equilibrium, an order in which a certain way of life and thought dominates. [10] This became the major theme in dealing with neglected children in Sydney through much of the nineteenth century.

King had established the Female Orphan School in George Street on the western side of Sydney Town near the Tank Stream and King's Wharf, in the vacated former residence of Lieutenant Kent who had left the colony. King purchased the building from Kent on behalf of the government for £1,539. Within a few years, it was overcrowded with destitute girls. It was a substantial Georgian building of two storeys that could hold 70 inmates and was on a large block of land. [11]

Governor Bligh, who followed King, reinforced this dominance when he expressed concern about the increase in the numbers of destitute children, especially girls. He had been ordered from above to provide for their education in an orphanage to 'render them useful and creditable members of society' and to take utmost care of their religion and morals in apprenticing them as domestic servants or settling them into marriage. A free grant of land was to be provided to prospective husbands, which could not be alienated during the life of the female grantee. [12]

Governor Macquarie and the Male and Female Orphan Schools

When Governor Macquarie arrived in 1810, he too expressed a grave disquiet about the lower orders and their disinclination towards legal marriage. The common practice that he called 'concubinage or cohabitation' disturbed him, particularly its detrimental effect on children.

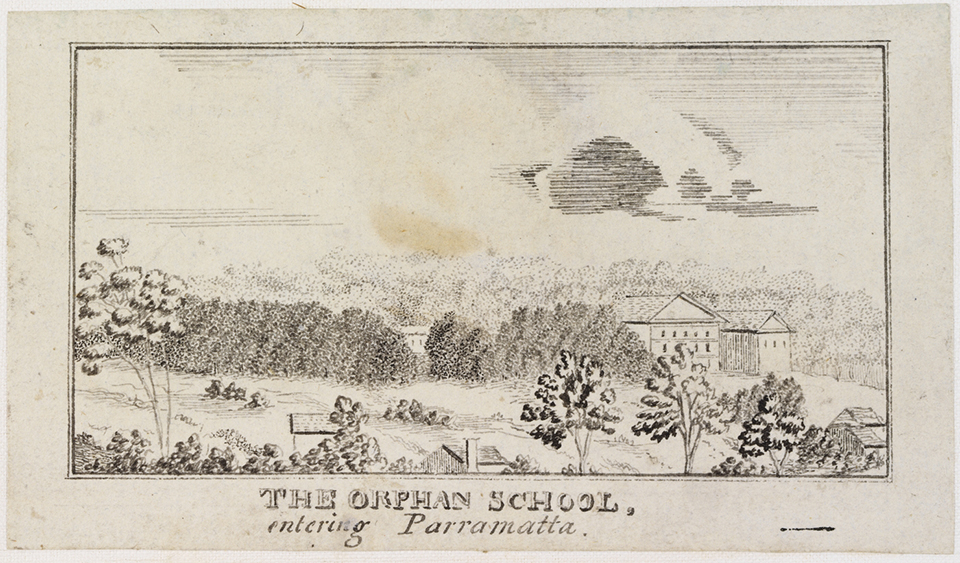

Like King before him, he was [media]worried about the growing number of neglected or destitute children in Sydney. Immediately, Macquarie restarted work on the building of the new Female Orphan School, which had been the King's brain-child, laying the foundation stone in September 1813. A substantial institution building had been planned on Arthur's Hill overlooking the Parramatta River on a 60-acre (24.3-hectare) land parcel. The building was completed in June 1818, [13] and still stands there today.

In the time that the girls resided in George Street, a pessimistic view of their reclamation was abroad. In a letter to the London Church Missionary Society, the Reverend William Pascoe Crook claimed that a large proportion of the girls released into the Sydney world from the George Street institution became prostitutes, and were little better while they were inmates. He also claimed that many older girls who had been received into the asylum had already embarked on a life of prostitution. [14]

To escape Sydney Town's temptations, the inmates were shifted to the new Arthur Hill buildings on 30 June 1818. The vacated property became the Male Orphan School but was later moved out west of Sydney Town to rural Liverpool. Macquarie took the opportunity to regularise control of the inmates and develop the activities of each asylum in a more efficient manner. The stated objects were largely identical: they sought to relieve, protect and provide their unprotected orphan inmates with lodgings, clothing, food and a suitable degree of 'plain Education'. 'Plain Education' was the central characteristic of eighteenth-century British charity schools set up for impoverished children. The design centred on engendering a sense of moral and religious duty so they would grow up to be faithful servants and exemplary parents.

The inculcation of habits of useful industry was to dominate in the colonial Orphan Schools. It was not a matter of moving out of the ranks to which they were born but a radical moral and religious reform of the lower classes that would still cling sensibly to their lower status in life. [15] The lower classes would be more easily controlled by a plain re-education process.

The social origins of the inmates of the Orphan Schools can be analysed from the extant applications for admission from 1825. Petitions frequently came from people temporarily caring for destitute, abandoned children or from single parents whose partner had either died or suddenly deserted. Some were the children of convicts transported for further offences to Newcastle, Port Macquarie or Moreton Bay. Some were children of mixed race – part-Maori or part-Aboriginal. Cases of mothers dying in childbirth were frequent, as were applications where the father had died. Several petitions were about fathers who were soldiers in regiments that were returned to England, leaving a common-law convict wife abandoned. Many were unidentified children who had been simply abandoned and were picked up in the streets by the police.

After training in the two asylums, children were apprenticed out as domestic servants, farm labourers or to tradesmen of various kinds. This approach was to persist in the mainstream of Sydney colonial life through to the 1880s, when it was challenged by the government's boarding-out system or foster child scheme.

The Female School of Industry

During 1826, advertisements appeared in the Sydney Gazette heralding the establishment of a third asylum for neglected children, the Female School of Industry. It was set up as a private institution based on voluntary support – on the British voluntary principle of charity control – rather than as a government institution like the two older orphan schools. It was run by a Ladies' Committee led by Eliza Darling, wife of the governor, rather than by a committee of government-appointed officials. It was established in Macquarie Street in a spacious two-storey Georgian building on a site where the Mitchell Library now stands. Later moved to Darlinghurst Road, into a building designed for the purpose, the Female School of Industry continued to produce domestic servants of various kinds until the mid-1920s.

Between 1801 and 1826, a system of child institutionalisation had been firmly established in Sydney and centralised there to cater for the whole colony. It comprised the compulsory detention of the individual until early adulthood (at the time, mainly 14 or 15 years of age), subsequent apprenticeship of long duration, monotonous industrial work within the asylum, with removal from all 'immoral and evil influences'. It was a dormitory system of child management with its concomitant mass feeding of a dull uniform diet and a rigid authoritarian form of schooling and training. Once the child became an inmate, parents were relatively powerless to assert their rights. The future destiny of their child was in the hands of the State. Children attending these asylums were readily labelled by the small Sydney community as objects of public charity. The future low social rank of the children was thus assured. [16]

By the 1830s with the strong revival of transportation, the two government orphan schools were rearranged into the Roman Catholic and Protestant Orphan Schools, along sectarian lines but still controlled and supported by the government. The Female Orphan School became the Protestant Orphan School, and the Male Orphan School (which was by this time at Liverpool) became the Roman Catholic Orphan School. Both of these newly-structured institutions housed both boys and girls in segregated dormitories. They lasted until the late 1880s.

The Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children

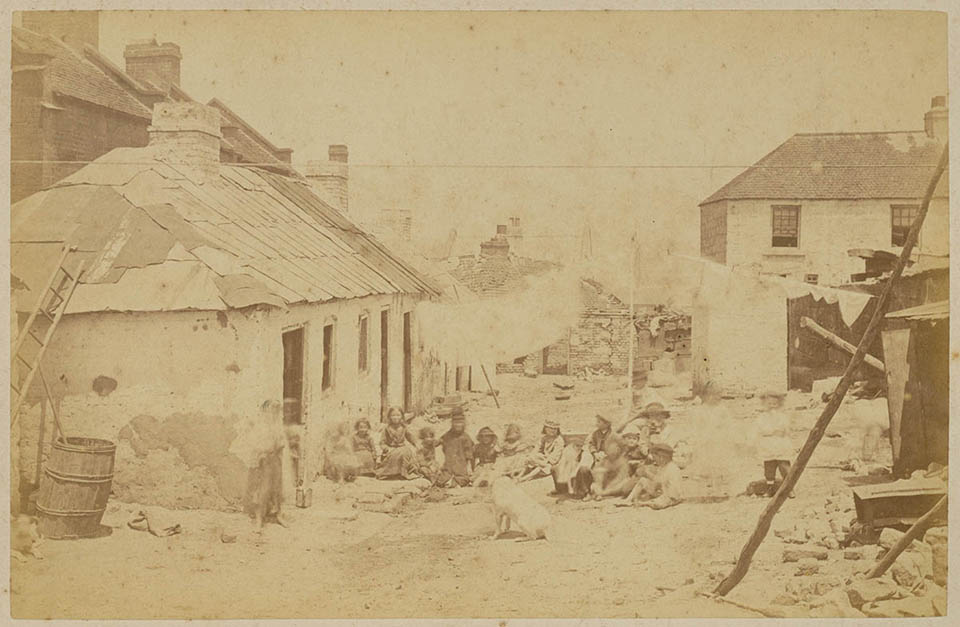

By the 1850s, there was [media]another alarming growth of child destitution centred on Sydney which had, by this decade, a much larger population. The crisis had emerged in the more densely populated lower-class areas of Sydney, where there was a rapid increase in the urban child population. The gold rush and its effect in dislocating family life was another factor. Accommodation was in dramatically short supply. There was thus a rapid growth of slum areas in the heart of Sydney with the dangers of high unemployment, family destitution, social collapse and high death rates from infectious diseases caused by unsanitary conditions.

Destitute [media]street children of the era eked out a living by street-selling, begging, petty crime, prostitution, and collecting food scraps from the city markets. A culture of poverty developed in the most economically depressed districts like Durand's Alley, The Rocks, the lower Sussex Street area and parts of Chippendale, where there existed abysmally poor housing, rampant prostitution and serious family dislocation.

Destitute, abused and neglected children found their way onto the mean streets of Sydney by well-trodden paths – occasionally orphaned, other times deserted, neglected or simply required to fend for themselves in the harsh urban environment. To the observer, there seemed no end to the supply of children in the streets and laneways as seen by the more sensationalist press. Resourcefulness and guile were the only commodities they could market. Street hawking, scavenging, sleeping out rough, begging and street prostitution were part and parcel of their everyday experience. Physical and sexual abuse were commonplace.

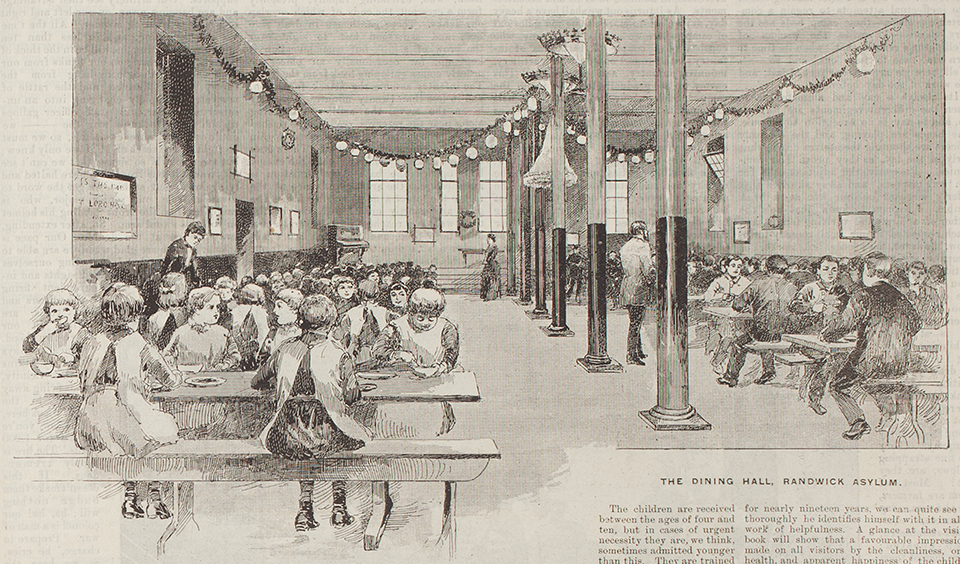

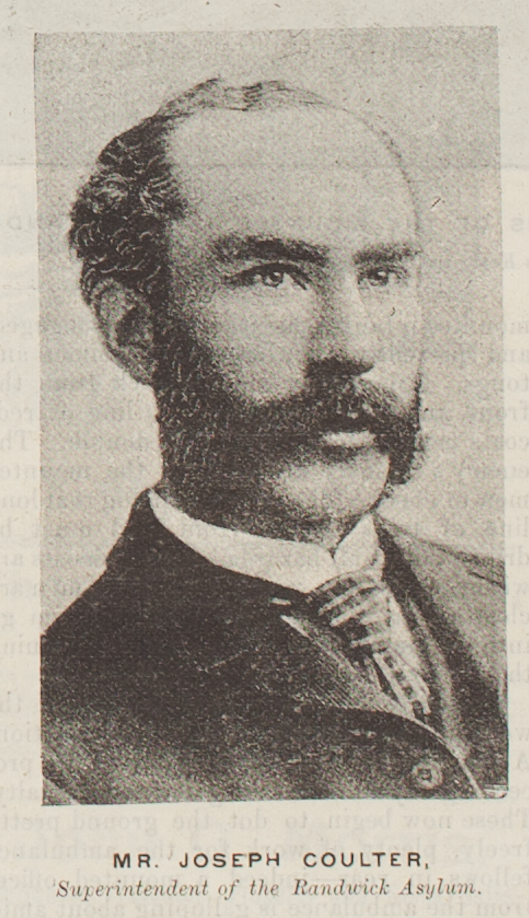

The usual [media]genteel middle-class solution was applied – the establishment of a large-scale child-saving institution to 'sweep the streets clean'. Such was the object of the Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children, which absorbed successive battalions of barefooted children within its secure honey-hued sandstone walls from the 1850s until April 1915, when it was taken over by the Commonwealth Government and converted into a military hospital (now part of the Prince of Wales Hospital).

The Randwick Asylum was a [media]sequestered place with children raised via 'batch-living' – a mechanistic, militaristic lifestyle that was intended to rescue and discipline children from the harsh but freewheeling streets and turn them into industrious God-fearing adults who knew their place in society. But such institutionalised en masse childcare brought with it new forms of physical abuse and social neglect. [17]

When the [media]famous English child-saving experts Rosamond and Florence Hill visited the Randwick Asylum in 1873, they found the massive place, run on private philanthropic lines, to be very similar to the 'large pauper schools' of England – the epitome of all that was bad in nineteenth-century child-rescue theory and practice. They reacted particularly to the appearance of the inmates:

They did not impress us favourably, either with regard to neatness of appearance or intelligence of countenance but perhaps this may be owing to their cropped hair and unbecoming dress. Dullness of expression, however, is not uncommon among children massed together as they are at Randwick where the numbers are so large that…neither superintendent or matron know even the names of many of their youthful charges. [18]

The Randwick children were frequently known by a number rather than a name.

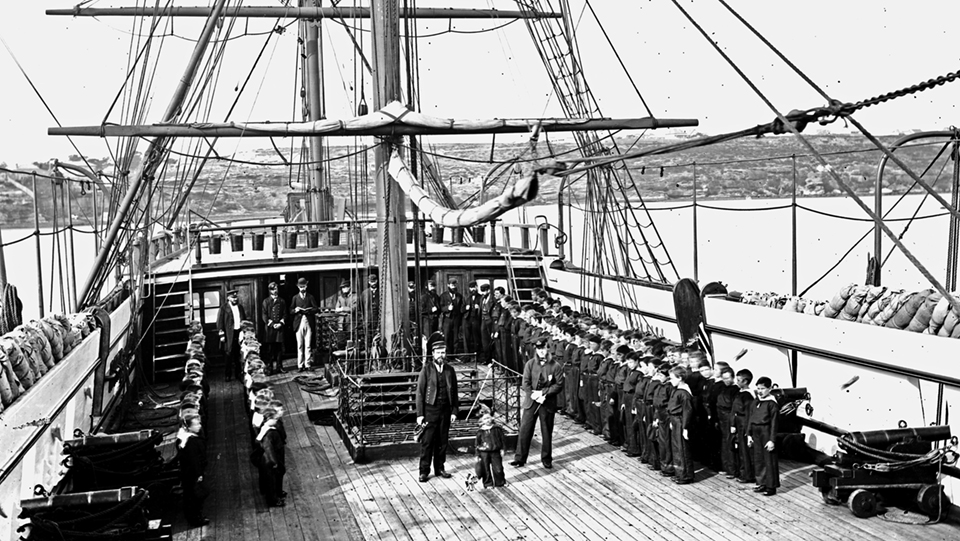

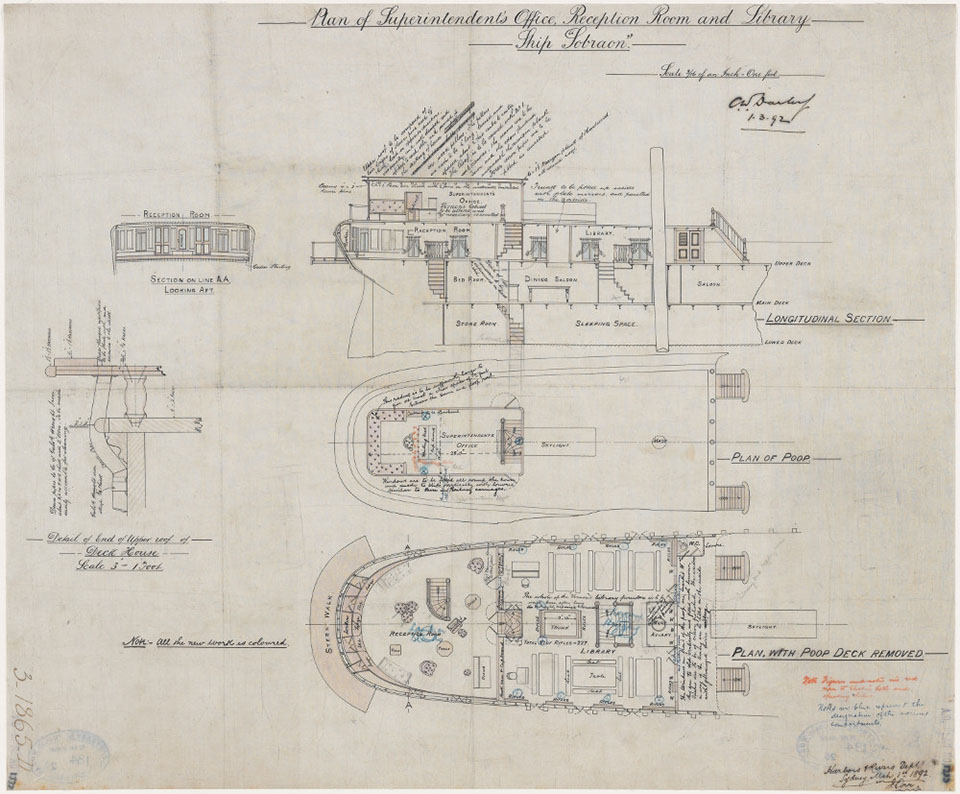

The Nautical School Ships

In [media]contrast, the boys of the Nautical School Ship were well known for the spick-and-speck smart neatness of their naval uniform and the brightness of their countenance, as well as superb physical fitness and work adaptability. The Nautical School Ship was founded in 1867 under the 1866 Industrial Schools Act, driven by Henry Parkes as Premier and James Martin as Attorney-General. In the harbour near Cockatoo Island, it provided residential care for destitute or neglected children. (The Girls Industrial School at Newcastle and later on Cockatoo Island under the same legislation was not such a success, but the worst kind of failure.) The NSS Vernon served as an industrial school from 1867 until it was replaced by the Aberdeen-built clipper passenger ship Sobraon in 1891. The Sobraon was completely [media]refitted for its new function as an industrial school providing pre-apprenticeship training for destitute boys between six and 18 years of age. The nautical industrial school concept in Sydney involved the complete institutionalisation of neglected, destitute or vagrant boys aboard the ship until they reached 18 years, if discharge for apprenticeship outside did not take place before that time.

Taking everything into account, the Nautical School Ship was a singular success as a child-saving institution of its type. The curriculum provided was an articulated mixture of elementary education and nautical and industrial training, with the purpose of developing the boys into useful, worthy and morally upright adult members of society. The main concern was in the reformative progress of the inmates, and the ship provided a rotating daily timetable of schooling, training, drill and work.

At [media]any one time, the Sobraon catered for about 400 inmates of various ages, mainly from six to 16. Ironically, the Sobraon became a symbol of a prosperous free colony and served to disguise uncomfortable realities about the unequal distribution of wealth and power. Boys incarcerated there were from the depressed edges of colonial society. [19]

The [media]boys were divided into six divisions. Each division was involved in a particular activity at a particular time. For example, three divisions would be in the well-equipped schoolroom under the guidance of a specially selected schoolmaster, one division would be at naval military drill, one would be involved in naval training, and one would be at trade training, either carpentry, tailoring or boot-making. (Each inmate was able to choose the particular trade training he wished to undergo.) The rotating daily timetable ensured that the use of all the educative and training resources aboard the Sobraon and earlier on the Vernon would be maximised. An atmosphere of energetic, if a little frenetic, total involvement by the inmates prevailed.

Sports and [media]recreation were not neglected. Recreational activities included gymnastics, cricket, rugby, swimming, playing in the brass band, maintaining animal pets, magic lantern shows in the recreation hall, and recreational reading in a well-stocked library. Sporting clubs were organised by committees of boys assisted by members of staff. These clubs played in Sydney and suburban district competition, especially rugby, cricket and swimming.

A recreation [media]ground was set up for the boys on Cockatoo Island adjacent to the ship's moorage, and a saltwater tidal baths was erected beside it. Larger pets such as an emu were kept on the fringes of the recreation grounds and smaller pets such as dogs and cockatoos were kept aboard ship to be cared for there. Regular public concerts were held aboard the Sobraon, and the brass band also played at prominent charitable occasions, such as open-air fetes in Sydney's parks. In 1908, a lifesaving club was formed on board with the support of the Royal Life Saving Society. In that year, 50 boys gained certificates of efficiency.

There were several key reasons for the closure of the Nautical School Ship Sobraon in 1911. The main problem was cost efficiency – it was an expensive institution for the government to run. Criticism of large-scale children's institutions had been mounting since the 1873–74 New South Wales Royal Commission into Public Charities, which had recommended the establishment of a system of boarding-out state children with responsible families and the use of smaller cottage-type institutions for children who could not be boarded out for various reasons. [20]

The boarding-out system triumphs

The boarding-out system, which had its origins in the British Isles in the mid-nineteenth century, became a reality in New South Wales in the 1880s. The idea was to board out orphaned and homeless children in homes of respectable persons under proper supervision, instead of herding them together in large public institutions. The foster homes for these children were frequently situated in country or rural districts where the children showed a marked improvement in health owing to pure air, greater variety of food and lessened risk of contagious diseases.

Earlier, the boarding-out scheme had been successfully implemented in South Australia and Victoria. The movement in Sydney started when Mrs Jefferis, the wife of the pastor of the Pitt Street Congregational Church, arrived from Adelaide. She became a well-publicised advocate of boarding-out. Together with other like-minded women, she obtained an interview with Henry Parkes who had just been elected Premier. He provided a small government subsidy of £200 at first to get things started. The New South Wales Inspector of Charities offered favourable support. Parkes backed the scheme completely by pushing the State Children 's Relief Bill through Parliament. It was passed on 5 April 1881 and provided for a State Children's Relief Board which acted vigorously, and the experimental stage was soon passed. A full-time Boarding Officer was appointed. Soon the Protestant and Roman Catholic Orphan Schools were emptied out and could be closed down, and all the government-supported children were removed from the Randwick Asylum to be boarded out, radically reducing its numbers. Other small Sydney child-rescue institutions were closed.

By 5 April 1886, 1,366 destitute and homeless children (779 boys and 587 girls) had been boarded out with responsible families, partly in the countryside and rural New South Wales, but many in Sydney itself. By April 1909, 3,846 children had been placed out apart from their parents with 2,534 guardians – for adoption, as boarders with maintenance, or as apprentices. [21]

Through the popularity of the boarding-out system, which was carefully inspected, the community of New South Wales in both city and country had accepted direct responsibility for the care of orphaned, abandoned and homeless children in a realistic and humane way to recreate the conditions of family life of which such children had been deprived.

The age of the large-scale institutions was over, but during the early years of the twentieth century smaller cottage-style institutions emerged in many Sydney suburbs, in major country towns like Bathurst, Goulburn, Orange, Armidale and Maitland and even in smaller rural towns. They were run by various denominational churches or private voluntary organisations. By the 1920s, they were heavily sprinkled across the map of New South Wales.

References

Hugh Cunningham, Children and Childhood in Western Society since 1500, Longman, London, 1995

Bob Bessant (ed), Mother State and Her Little Ones, Centre for Youth and Community Studies, La Trobe University, Melbourne, 1987

Brian Dickey, 'Industrial Schools and Reformatories in New South Wales 1850–1875', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 54, pt 2, June 1968, pp 135–51

Brian Dickey, 'Care of Deprived, Neglected and Delinquent Children in NSW 1910–1915, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 63, pt 3, December 1977, pp 167–83

John Ramsland, 'The Development of Boarding-out Systems in Australia 1860–1910', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 60, pt 3, September 1974, pp 186–98

John Ramsland, 'Life Aboard the Nautical School Ship Sobraon, 1891–1911', The Great Circle, vol 3, no 1, April 1981, pp 30–45

John Ramsland, 'The Sydney Ragged Schools. A 19th Century Voluntary Approach to Child Welfare and Education', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 68, pt 3, December 1982, pp 222–37

John Ramsland, 'An Anatomy of a Nineteenth Century Child-Saving Institution. The Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 70, pt 3, December 1984, pp 194–209

John Ramsland, 'Barney Kieran, the Legendary “Sobraon Boy”. From the Mean Streets to “Champion of the World”', Sport in History, vol 27, no 2, June 2007, pp 241–59

John Ramsland, Children of the Backlanes: destitute and neglected children in colonial New South Wales, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1986

John Ramsland, 'The Education and Care of Destitute, Orphan, Neglected and Delinquent Children in New South Wales', PhD thesis, University of Newcastle, January 1982

Richard George Van Wirdum, 'The Forgotten Generations. The Physical, Sexual, Psychological and Systematic Abuse of Children Due to Management Practices in Children's Institutions in Australia 1801 to 2001', PhD thesis, University of Newcastle, August 2008

Notes

[1] John Ramsland, Children of the Backlanes, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1986, p 1

[2] Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 3, facsimile reprint, Lansdowne Slattery, Mona Vale NSW, 1978, p 184; also in G Mackaness, Some letters of Rev Richard Johnson BA. First Chaplain of New South Wales, part 2 rev ed Review Publications, Dubbo NSW, pp 18–42

[3] Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 3, facsimile reprint, Lansdowne Slattery, Mona Vale NSW, 1978, pp 146–60

[4] Rev S Marsden to W Wilberforce, 6 February 1800, Bonwick Transcriptions Box 49 – Missionary, vol 1, p 78, Mitchell Library; JF Cleverley, The First Generation – School and Society in Early Australia, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1971, p 89

[5] Hugh Cunningham, Children & Childhood in Western Society Since 1500, Longman, London, 1995, p 134

[6] Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 4, facsimile reprint, Lansdowne Slattery, Mona Vale NSW, 1978, p 658

[7] Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 5, facsimile reprint, Lansdowne Slattery, Mona Vale NSW, 1978, p 115

[8] Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 5, facsimile reprint, Lansdowne Slattery, Mona Vale NSW, 1978, p 115

[9] Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 6, facsimile reprint, Lansdowne Slattery, Mona Vale NSW, 1978, p 401

[10] Cited in Bob Bessant (ed), Mother State and Her Little Ones, Centre for Youth & Community Studies, La Trobe University, Melbourne, 1987, p 9

[11] John Ramsland, Children of the Backlanes, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1986, p 4

[12] Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 6, facsimile reprint, Lansdowne Slattery, Mona Vale NSW, 1978, p 401

[13] John Ramsland, Children of the Backlanes, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1986, p 11

[14] Crook, Rev WP to Church Missionary Society, London, 18 June 1813, Bonwick Transcriptions, Box 49 – Missionary, vol 1, Mitchell Library

[15] John Ramsland, Children of the Backlanes, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1986, p 12

[16] John Ramsland, Children of the Backlanes, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1986, pp 11–21

[17] John Ramsland, 'An Anatomy of a Nineteenth Century Child-Saving Institution. The Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 70, pt 5, December 1981, pp 194–209; John Ramsland, 'Behind Sandstone Walls: Destitute Children and the Randwick Asylum', Papers and proceedings of Scenes from Childhood, Independent Scholars Association of Australia, NSW Chapter, Canberra, 2010, pp 15–24

[18] Rosamond and Florence Hill, What we saw in Australia, Macmillan, London, 1875, pp 306–7

[19] John Ramsland, '"Barney Kieran, the Legendary Sobraon Boy": From the mean Streets to “Champion of the World”', Sport in History, vol 27, no 2, June 2007, p 245

[20] John Ramsland, 'Life Aboard the Nautical School Ship Sobraon, 1891–1911', The Great Circle, vol 3, no 1, April 1981, pp 30–45

[21] John Ramsland, 'The Development of the Boarding-out System in Australia 1860–1910, The Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 60, pt 3, September 1974

.