The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Colebee and Nurragingy's land grant

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Colebee and Nurragingy's land grant

In 1983 the New South Wales Government passed laws that recognised Aboriginal rights to land – the Aboriginal Land Rights Act NSW 1983. These laws, which pre-dated the High Court's 'Mabo' decision by a decade, responded to Aboriginal people's campaign over many generations for recognition of traditional rights over territory. As European occupation intensified and resources were depleted, Aboriginal people sought secure land to settle. The Aboriginal Land Rights Act amounted to a social justice package, funded for 15 years, encompassing a mechanism to recover limited land held by the Crown and a network of representative Aboriginal organisations to manage land and cultural heritage.

The New South Wales Act was a comprehensive response to Aboriginal land justice claims and has endured for more than 30 years. However, since colonisation, there have been rare instances where the colonial government recognised Aboriginal interests in land, and made land grants. The motivations for these limited and prescribed land grants ranged from reward for cooperation with the colonial forces, to small-scale allocations for farming and, in later years, many became sites for close government management, surveillance and segregation of Aboriginal people. These grants were not informed by an understanding of traditional attachment to place, although this continued to be an important factor for Aboriginal residents. In most instances, such grants came to be irregularly revoked by the Crown over time – including the blanket revocation of reserve lands as late as 1983 while negotiations over the form and content of the 1983 Aboriginal Land Rights Act were taking place.

Colebee and Nurragingy land grant, 1819

On 31 August 1819, under the rule of reformer Governor Macquarie, two Aboriginal leaders, Colebee and Nurragingy, were granted 30 acres (12.1 hectares) of land located on the Richmond Road at the intersection of what is now Rooty Hill Road. Although the registration of the land grant was in Colebee's name only, the land continued to be occupied by Nurragingy until his death and formed the crucial locus for several more land grants and the establishment of the Black Town Native Institution.

The site was resumed by government in the 1920s, and more recently was partially developed as a housing estate, but it continues as a space that connects pre-colonial traditional Aboriginal people with post-contact Aboriginal modernity and where the justice claims of post-colonialism await.

The land granted by Governor Macquarie to Colebee and Nurragingy (who was also referred to in colonial records as 'Creek Jemmy') was a reward for 'fidelity to Government and their recent good conduct' as native guides and, significantly, 'to have and to hold forever'. Governor Macquarie also honoured Nurragingy with his 'Order of Merit' giving him a brass breastplate inscribed with his name: 'Nurraginjy, alias Creek Jemmy' and styling him 'Chief of the South Creek Tribe'. The issuing of breastplates was inaugurated by Macquarie at the Parramatta feasts and was probably seen as a means to create a comprehensible power hierarchy and to persuade Aboriginal leadership to place their children with the newly established Native Institution.

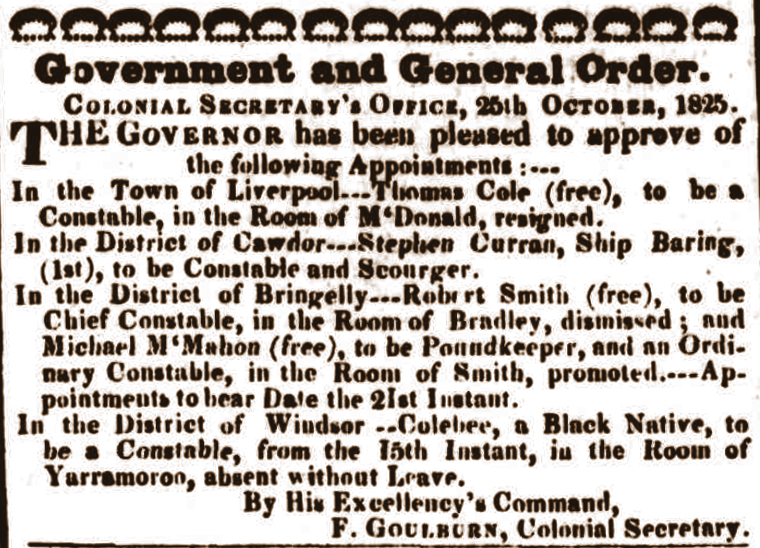

The breastplate also places Nurragingy's tribal affiliation in the locale of the Richmond Road land grant. Colebee on the other hand, while formally granted the land, had traditional land affiliations further west towards Richmond, hence his title 'of the Richmond Tribe'. Colebee accompanied William Cox in building a road across the Blue Mountains and [media]later worked as the Native Constable at Windsor. Records show he married Black Kitty, who was at the Parramatta Native Institution from 1814, in 1822.

The location of the land grant was significant because it was apparently nominated by Nurragingy. Ongoing archaeological work continues to reveal the presence of stone artefacts and the important source of silcrete, a hard stone useful for making hunting equipment which would also have been a useful trading substance before and after the Europeans arrived.

Maria Lock's land

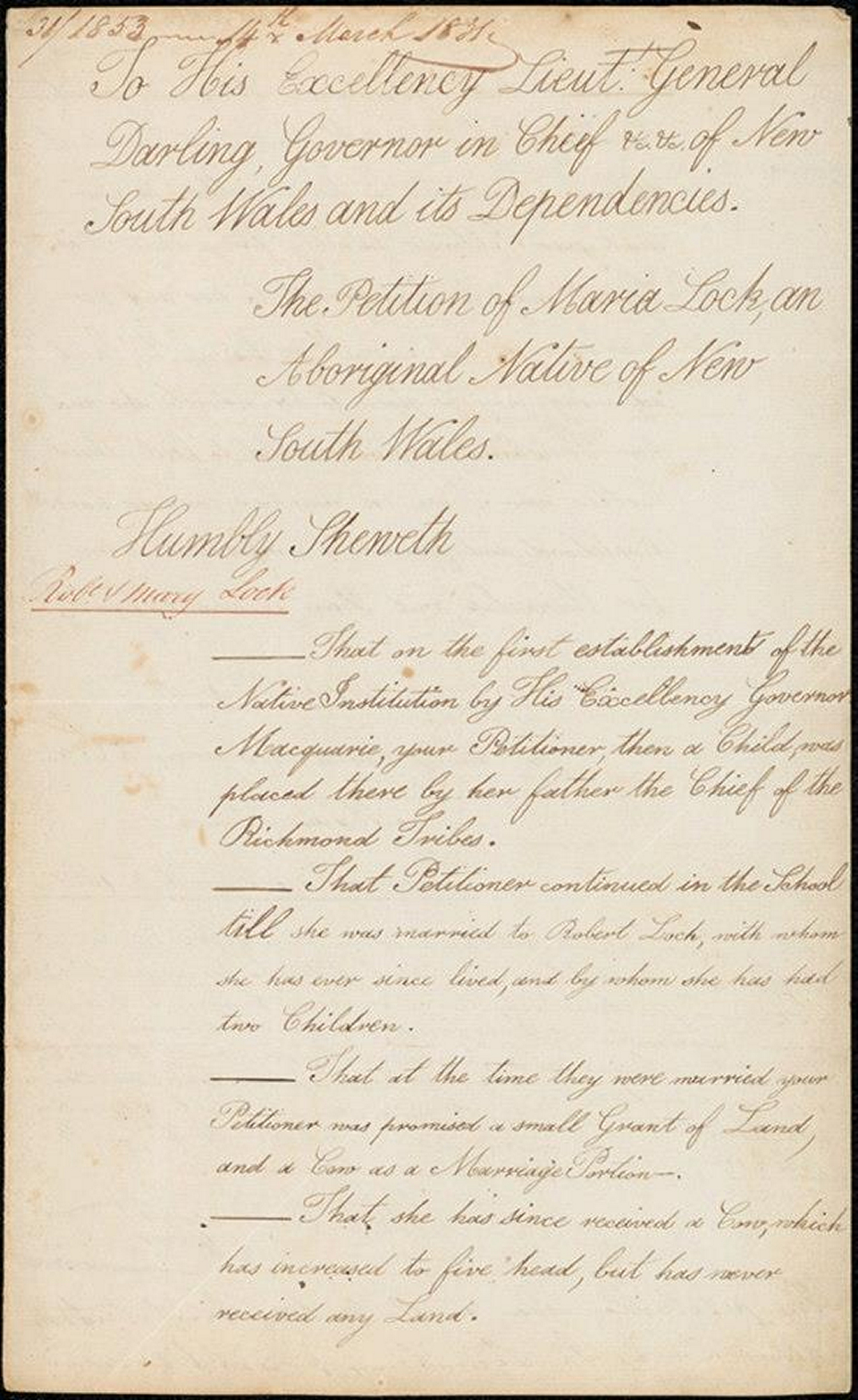

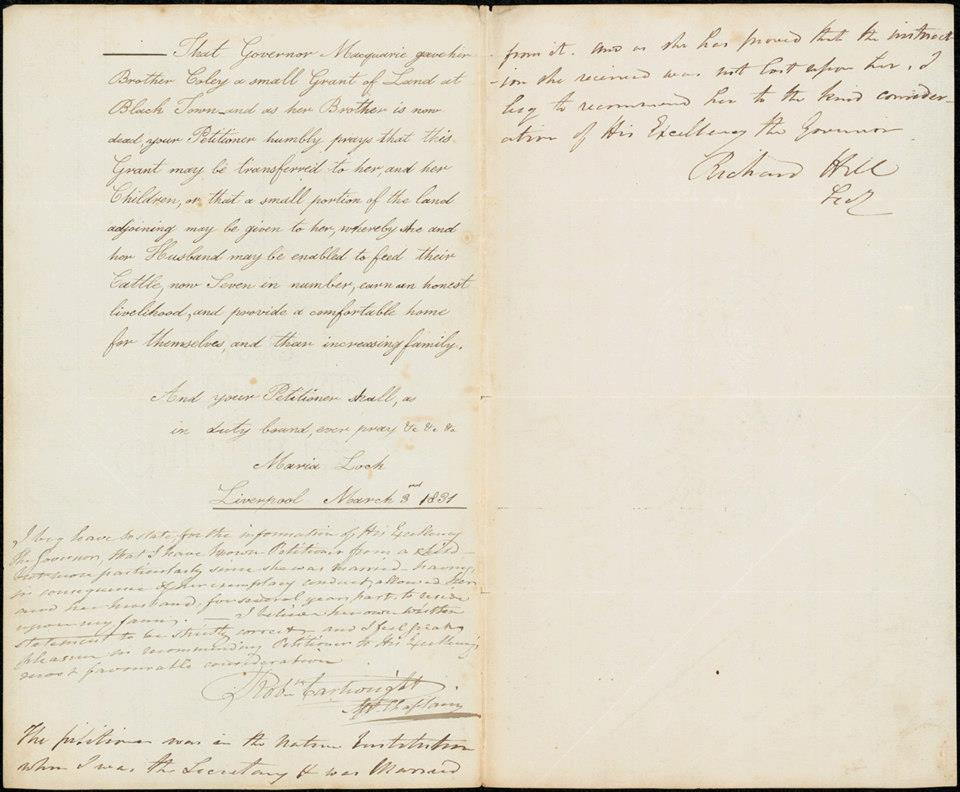

[media]With the passing of Colebee and Nurragingy, Nurragingy's two sons [media]and Colebee's younger sister, Maria Lock, petitioned the Governor in 1843 for the transfer of the 1819 land [media]grant. Maria, who had won prizes from the Parramatta Native Institution in 1815 and already owned land at Liverpool, was granted the land because the land grant was registered in her brother Colebee's name. Although Nurragingy had lived continuously on the land, the grant was passed to Maria who took up residence there in 1843–44 with her husband and ten children. They went on to acquire the adjacent 30 acres (12.1 hectares) that had been the site of the Native Institution from 1822.

When Maria died in 1878, her significant land holdings – 60 acres (24.3 hectares) at Black Town and 40 acres (16.2 hectares) at Cabramatta Creek, Liverpool – were equally shared among her nine surviving children. Maria and Robert Lock's children and their families continued to live on their Black Town lands until the early 1900s when they are likely to have been removed for rates arrears or because the Aborigines Protection Board assumed greater control over Aboriginal lives. A descendant, Colin Gale, recalled his family's stories about the Locks moving to a mission in southern New South Wales:

My mother and father and grandmother and all them, all spoke about Miss Thompson…She took [the Lock children] to Bomaderry in 1908 and she set up the Bomaderry Mission officially in 1911. [1]

By the 1920s, the Black Town land once owned by Maria was considered an Aboriginal reserve (Plumpton) and title was revoked by the Aborigines Protection Board. [2]

Darug claims to the site

Aboriginal land claims to the site, either as compensation under the NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 or as a result of traditional and continuous occupation under the Native Title Act 1993, have been unsuccessful despite the documented record of land title and occupation on the Richmond Road 'Black Town' lands.

The Darug Tribal Corporation has long argued for the return of the land granted to Colebee and Nurragingy and for the Black Town Native Institution site adjacent to it. Elder Sandra Lee said, in April 2013, that the Black Town Native Institution site:

…is part of the ongoing history of Aboriginal peoples' struggle for land rights. It's time the site is celebrated within our broader community so that it receives the recognition it deserves. [3]

In 2012 the site was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register. [4]

References

Brook, Jack and JL Kohen. The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town: A history. Kensington: University of New South Wales Press, 1991.

Hinkson, M. Aboriginal Sydney: A guide to important places of the past and present. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2001.

Soon, N. 'It's time to give it back', Blacktown Sun, 29 April 2013.

Notes

[1] Colin Gale, interview for 'Fighting For and Losing our Land 1 – The Lockes and Land Grants', A History of Aboriginal Sydney, http://www.historyofaboriginalsydney.edu.au/west/fighting-and-losing-our-land-1-%E2%80%93-lockes-and-land-grants-colin-gale, viewed 7 January 2015

[2] Naomi Parry, 'Lock, Maria (1805–1878)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lock-maria-13050/text23599, published first in hardcopy 2005, viewed 21 January 2015

[3] N Soon, ‘It's time to give it back’, Blacktown Sun, 29 April 2013

[4] Hon Robyn Parker MP, Minister for the Environment, Minister for Heritage, 'Colebee Nurragingy Land Grant receives honour of State Heritage', media release, Tuesday, 7 February 2012, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/heritagebranch/heritage/media/ColebeeNurragingyLandGrant.pdf, viewed 21 January 2015