The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Dr Iza Coghlan

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Iza Coghlan

[media]Iza Coghlan was the one of the first two women in New South Wales to graduate in medicine at the University of Sydney in 1893. With Grace Fairley Robinson, she was the second Australian woman doctor to register with the New South Wales Medical Board. Iza pioneered private medical practice in Sydney and was the first Sydney woman doctor to operate two long-standing concurrent practices. Dr Coghlan formed the first women’s life-saving class in New South Wales, and established the New South Wales Medical Women’s Association, serving as its first president. She dedicated her later career to the health and welfare of school children across New South Wales, serving as government medical officer to the Department of Public Instruction.

Early life in Redfern

Iza Coghlan was born Frances Josephine Coghlan in Redfern, on 10 October 1868, to Irish-born Catholic Thomas Coghlan, plasterer, and his Protestant wife Dorcas.

Iza Coghlan, also known to her family as ‘Fan’ or 'Fanny', was the eighth of nine children and lost her father when she was 13. Iza’s widowed mother continued to raise her children in the religion of their father, and held great aspirations for them. She made sacrifices to ensure Iza and her siblings received schooling that would enable them to access the higher professions, and also helped educate them herself.[1]

Historian Louella McCarthy has noted their working-class beginnings in ‘one of the narrowest little back streets of Redfern.’[2] In spite of this, the family became well known in Sydney because several of the Coghlan children went on to forge distinguished careers. Iza’s brothers included first government statistician of New South Wales Sir Timothy Augustine Coghlan, barrister Sir Charles Augustus Coghlan, and solicitor Cecil Aubrey Francis Coghlan. Her sisters included feminist suffragist public servant clerk Dora Beatrice Coghlan Murphy, teacher Lucy Jane Coghlan, and sculptor Dorcas Christina Coghlan.[3]

Education

Iza entered Sydney Girls’ High School in the first intake of 39 students in 1883, the school’s foundation year. The register lists her entry age as 12 but she was in fact 15. After passing the competitive entrance examination she was awarded a merit scholarship as one of the top 11 students. She left school on the last day of 1886.[4]

Iza was part of the first cohort of girls in Sydney to take advantage of a public high school education. Unlike private ladies’ academies that prioritised the accomplishments, the Sydney Girls’ High School taught the Public School Curriculum, which enabled girls to enter public examinations, the University of Sydney, and potentially a professional life. Significantly, girls were taught physical science, which meant they had a greater likelihood of success if they wanted to complete a degree in medicine at the University of Sydney, which had accepted its first woman student in 1885.

Iza’s older sister Dora had fought for many years for women’s rights to enter higher education, and is likely to have been influential in Iza’s decision to apply to enter University in 1887. Her brother Timothy assisted by taking financial and educational responsibility for Iza from the time of his first salary.[5] At this time the cost of undertaking a university degree in Australia was very high.

University of Sydney

Iza passed her matriculation examination in 1887 after receiving tuition from Edward Blackmore, was admitted as a member of the University of Sydney on 31 March 1887, and successfully passed the first year of arts. In 1888 she enrolled in Medicine in the sixth intake of students, becoming the second woman to enter the faculty. During this year she was the first woman medical student to be elected a member of the university's Medical Society.[6]

Iza’s rigorous study in 1888 was rewarded with a pass in her first professional examinations in medicine one year later. She excelled in surgery, and this was recognised with the award of a special annual prize to the value of £10 given by Dr Frederick Milford, which she shared with Frank Tidswell for the year 1889.[7]

Iza succeeded in medicine with particular talent in class examinations in clinical surgery until 1891, when she failed her second professional examinations in her fifth year of medicine. She repeated the year and successfully passed in 1892, but only when classmate Grace Fairley Robinson had caught up to her.

The Ladies’ Tennis Club

[media]In 1892 Iza served as an office bearer of the Ladies’ Tennis Club at the University, tennis being the most popular sport for women students, with more than half its women undergraduates as members.[8] The club played an empowering part in women students’ academic lives and identity, as it was one of the few University activities where they were able to interact socially.[9] It is notable that Iza joined after failing her important second professional examinations, suggesting she was seeking not only sport, but also female support and camaraderie in a learning environment dominated by men and male networks.

The first woman to graduate in medicine in Sydney

In 1893 Iza undertook her third professional examinations, passed with credit in the final examination, and became, with Grace Fairley Robinson, the first women to graduate in medicine in Sydney, graduating Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery (MB MS). To show his support for Iza’s achievement, Professor James Thomas Wilson, Challis Professor of Anatomy, gave her a gown and hood to wear at her graduation ceremony.[10]

Remarkably, Iza’s graduation garnered little attention in Sydney’s major newspapers despite the fact that the University of Sydney was the first university in Australia to allow women to enrol in medicine. The Freeman’s Journal devoted a short column to the success of ‘our Catholic lady doctors’, and The Bulletin commented:

These two women-students have at last succeeded in breaking through the barriers which the Sydney University authorities have persistently opposed to the admission of women to medical degrees. The experiment of medical women is one that must in the end succeed, despite the mass of stolid prejudice which stands in the way.[11]

The Sydney Morning Herald mentioned the women’s achievements in passing, as part of a general article devoted to the university commemoration, describing the formal conferment of degrees, which were:

… in the majority of cases accompanied by cheering on behalf of the undergraduates, who were especially enthusiastic on behalf of ... Miss Iza Frances J Coghlan and Miss Grace F Robinson, the first two young women to gain distinction in the faculty of medicine.[12]

Pioneering private medical practice in Sydney

On 12 April 1893, Iza and Robinson registered with the New South Wales Medical Board, the second Australian women doctors to do so after Frances Dick.[13] The highly prized resident posts in the city’s two major teaching hospitals, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and Sydney Hospital, were not open to women doctors when Iza graduated. So pragmatically, she established a private practice as ‘physician’ at Nithsdale, 167 Liverpool Street, near Hyde Park, and then the heart of Sydney’s prestigious medical district. To add to her list of pioneering achievements, she was the first Australian-trained woman doctor to open a private practice in Sydney, following overseas-trained woman doctors Dr Dick and Dr Margaret Corlis who had both opened shorter-term consulting rooms in Sydney in 1892.[14]

The city block housing Iza’s practice was home to the private practices of male doctors and surgeons, however Iza’s building also contained dentists and a dancing school. Establishing a private practice was costly and took time, especially considering the general public in Sydney had very little experience consulting women physicians. Perhaps Iza’s influential, well-connected siblings helped her with financial support network these early professional years. Her suffragist sister Dora is also likely to have referred numbers of politicised Sydney women who were keen to consult a female doctor, to avoid medical subordination to a male. Sydney author Ethel Turner clearly trusted her schoolmate Iza’s medical competence, as Turner’s diary entry of 23 April 1894 describes her consultation, prescription, and reveals, ‘I wouldn’t go to a “man” doctor.’[15]

Lecturing in public health in Sydney

Whilst in private practice, Iza juggled multiple working roles. In June 1893 she began lecturing on public health in Sydney, and gave the inaugural lecture of the Ladies' Sanitary Association on domestic remedies, the treatment of fevers, and throat and chest complaints, to an audience of women in the city’s YMCA Hall.[16] Many early women doctors like Iza took part in public arenas as a way of establishing their identity in their male-dominated profession, while aiming to educate and empower girls and women, as many lacked basic knowledge about their own bodies.

First medical examiner for women at AMP

In 1894, whilst running her private practice, Iza was appointed in Sydney as the Australian Mutual Provident Society’s (AMP) first ‘approved’ medical examiner for women. The Society created Iza’s role to meet the great demand from women seeking life assurance, and to offer them the choice of examination by a female doctor. At this time, insurance work was a significant element of general practice, particularly for doctors trying to create a patient base and establish a name. Women doctors in private practice were active in this kind of work in New South Wales from the 1890s, with Iza being one of over 40% who used AMP medical examinations as a way of attracting clientele prior to 1905. It was critical work for Sydney women doctors to take on if they wanted to maintain a successful general practice.[17]

Balmain Ladies’ Swimming Club

By the end of the nineteenth century, amateur swimming was growing in popularity in Sydney, and Iza was actively involved in its development. In 1894 she formed and instructed the first women’s life saving class in New South Wales at the Balmain Ladies’ Swimming Club at Elkington Park Baths. Life saving was a new movement at this time, and squad club members attended her drill classes and performed public exhibitions at onsite ladies’ swimming carnivals and gala nights. In 1895 Iza was appointed the club’s first honorary medical officer, a position she held until at least 1897.[18]

First Sydney woman doctor to operate two concurrent private practices

[media]Iza became a well-known woman doctor in Sydney, and by June 1896 she and Dagmar Berne were the ‘only two ”lady doctors” who sport brass plates in Sydney.’[19] Although it was difficult for many men and women doctors to make a living from medicine in the years leading up to World War One, Louella McCarthy argues that Iza was successful in building up her first city practice, as it was long term and she was able to expand. From 1900 Iza established a second suburban practice as ‘surgeon’ in Ashfield, the first Sydney woman doctor to operate two concurrent practices.[20] Her family owned land at 258 (later numbered 57) Liverpool Road, Ashfield from 1897. From 1900-15 she practiced here at the house Ashbourne, which carried the name of her mother’s Irish birthplace. Iza lived here with various siblings.

Leisure, philanthropy and the Sydney Medical Mission

Few descriptions of Iza exist, however Sydney author Lilith Norman wrote:

Like so many of those early women she was generous, popular, bright as a button, and had a wide range of outside interests, especially current affairs.[21]

In 1899, Iza served as honorary secretary to the burgeoning Field Botanists’ Society of New South Wales, which afforded members ‘opportunities of extending their knowledge of the science of botany by means of lectures, discussions, exhibitions of specimens and excursions in the field.’[22]

Iza and her sister Dora maintained their interest in Sydney feminism, both subscribing to Louisa Lawson’s journal The Dawn. In 1900, in the aftermath of Lawson’s electric tram accident that left her debilitated for a year, Lawson requested the additional medical care of Iza for her uterine injuries:

The services of a skilled lady-doctor, Dr Iza Coghlan, were asked for by Mrs Lawson, to supplement those of Dr Hall, when certain of the internal organs were found to be prolapsed, and the muscles supporting them to have lost their tone in consequence of the accident.[23]

One year later Iza was appointed lecturer to the St John Ambulance Association to instruct first aid classes for girls in Sydney.

She also supported philanthropic ventures, undertaking honorary work with Dr Julia Carlile Thomas at the Sydney Medical Mission. The mission served an important role for beginning women doctors seeking experience with hospital outpatient work, and provided free outpatients and home attendance medical and pharmaceutical services. [24]

Iza also served as a foundation member of the Old Girls’ Union at Sydney Girls’ High School, championing its fundraising causes over many years. Its pupils donated money and other support to the Sydney Medical Mission from its inception.

New South Wales Medical Women’s Association

With so few women doctors practicing in Sydney, women-focused professional bodies were a necessary and vital supportive resource. In 1900 Iza established the New South Wales Medical Women’s Association in Sydney and served as its first president. It was the second women’s medical association to be established in Australia after the Victorian Medical Women’s Society in 1895. Little is known about the New South Wales association as its early records appear to be lost, however its meetings took place in the consulting rooms of both Iza and its members, until lack of regular member attendance due to employment workload caused the society to fold in 1908.[25]

Following the demise of this society, in 1908 Iza was elected a member of the New South Wales branch of the British Medical Association, one of the few women doctors of her generation to join. She remained a long-term member until her retirement and continued even as a retired member.[26]

Government consulting physician

Iza maintained a heavy workload. In 1910, whilst operating her two practices, she was appointed examiner of applicants for admission to permanent employment in the Commonwealth Public Service. She was the Government Consulting Physician, in a non-public service role, and was paid a small retaining fee to report to the Public Service Commission on applicants with special cases of illness.[27]

The end of private practice

By 1914 and the start of World War I, Iza had relocated her city practice to Waratah Chambers at 179 Elizabeth Street, after practicing at Liverpool Street for 20 years. One year later she gave up both her city and suburban practices when on 4 March 1915 she was appointed schools’ medical officer in the Department of Public Instruction in New South Wales[28] as the role stipulated ‘no private practice.’[29] Iza took up the position soon after the resignation of Dr Grace Fairley Boelke, with whom she had graduated. Dr Boelke had fought with the department over her salary, seniority and its medical inspection system.[30] Like Boelke, Iza was appointed on a salary lower than other beginning male medical officers despite holding university qualifications that were identical.

By 1915 schools’ medical officers in New South Wales were directed to examine the health of each pupil every four years. They travelled in pairs to government, non-government, and Aboriginal schools, and to children placed in Metropolitan Shelters. In her first year, Iza visited school children for short periods in Taree, Yass, Albury, Wellington and Broken Hill, as part of a ‘travelling hospital’ for more remote areas of the state that lacked local doctors. It initially included a dentist, optometrist and nurses, who travelled together by train with heavy medical kits in a denoted carriage. Her role was one of constant travel.[31]

Inspections by schools’ medical officers had to be carried out within strict time limits, with a child fully examined every six minutes.[32] Iza's duties included weighing and measuring pupils, inspecting hair, ears, eyes, teeth, throat, nose, speech, and evaluating their ‘mental condition’, with recorded results collected for government statistical analysis. During these early years, doctors also gave general treatment and administered anaesthetics when performing operations such as removal of adenoids and enlarged tonsils.

As many country children did not have access to hospitals, their families could only afford to consult a doctor in medical emergencies. So as part of her role Iza addressed parents, and parents and citizens associations in the classroom after school, gave lectures on child health, care and upbringing, and suggested remedial and preventative solutions for medical complaints. As well, schools’ medical officers taught older girls about hygiene and baby care, examined the health of pupils entering teacher-training colleges, and undertook public health measures such as inspecting health hazards in school buildings.[33]

During 1915 Iza also helped to raise fund for the war effort and was one of many who signed the ‘Rylstone Autograph Quilt’ made in the the Central Tablelands of New South Wales. Made of white linen, the single bed sheet contained white cotton embroidered autographs as part of a quilt to commemorate wounded and killed Australian soldiers in Gallipoli.[34]

Appeal for equal pay

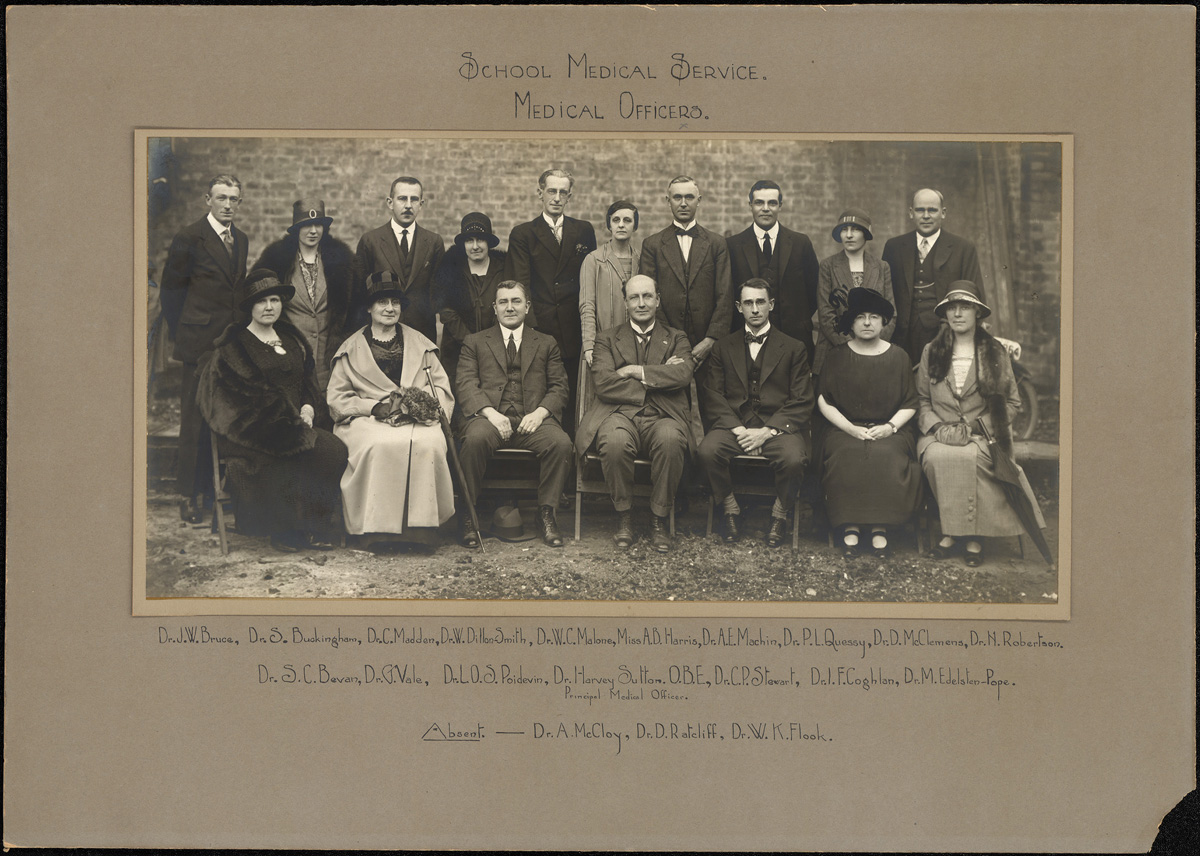

[media]By the 1920s school medical work had considerably expanded. It offered new fields of treatment and was considered almost a specialty in itself. By 1925 there were 18 full time schools’ medical officers in the Department of Education’s medical service in New South Wales. Their working conditions remained difficult however, and their salaries were distinctly lower than those paid to medical officers with similar status and duties in other public service departments.

Women medical officers such as Iza were doubly discriminated against. In November 1925 her colleague Dr Mary Edelsten-Pope wrote a letter to Professor Harvey Sutton, principal medical officer of the medical service, appealing on their behalf: ‘The junior male medical officers get a higher salary than the senior women and even higher than the senior women doing special work’.[35]

Professor Harvey Sutton responded to Edelsten-Pope’s request with a successful appeal to the Public Service Board for a salary increase for both men and women officers, including himself. In spite of this long-awaited victory, and Sutton’s additional suggestion that there be ‘equal pay for equal position, status and service’ for women medical officers, their newly-raised salaries still remained lower than those of men.[36]

Iza worked as schools’ medical officer for 15 years, rising to the position of deputy principal in 1925. Although well respected in her senior role, and described by Professor Harvey Sutton as ‘a careful and conscientious physician whose diagnoses, whether in children at Bourke or Balmain, I never had cause to question’, Iza was never remunerated accordingly in her lifetime. Dr Jean Armytage, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital pathologist, wrote of this prejudice towards Iza and women doctors in 1994:

She was a sweet and gentle woman who eventually became the deputy principal medical officer of the school medical service, paid, I might say, less than the most junior male medico on the staff! Those early medical women had to be something special to deal with their circumstances at that time.[37]

Iza relinquished her public service appointment in 1930 when she retired. Even at the end of her career, working conditions remained inequitable for men and women doctors in the service. Their professional work with children was not valued, and the medical branch of the Department of Education still had problems recruiting staff to the peripatetic, comparatively poorly paid role.

Honours and retirement

From 1927 Iza lived at 7 Bedford Crescent, Collaroy Beach at Delvinehara, the weatherboard cottage she owned and shared with her surviving sisters Lucy and Dorcas. She travelled overseas for pleasure, visiting Italy in the first year of her retirement.

During the 1930s, Hornsby Girls’ High School chose Iza as the ‘head’ of their red Coghlan House. She consented to its naming in honour of her inspiring leadership as one of the first women medical practitioners in New South Wales. The 1934 edition of the school magazine The Hornsby Torch contextualised her achievement:

Looking back over the years and then noting how today women doctors are accepted as a natural phenomenon … one realises the bravery and strength of purpose shown by the women pioneers who entered the arena of the medical profession. Though many approved, a greater number, not only disapproved, but were antagonistic. The objections were that women would coarsen and at least their finer susceptibilities would be blunted, that these women were invading the professions of men, that they would not have the nerves or mental balance of men, and so on.[38]

Family memories help to paint a more personal picture of a woman pioneer very much in the public eye of late Victorian and Edwardian Sydney. Iza’s great niece Beatrice Proust remembered Iza as:

… a diminutive woman, wearing her hair in a bun on top of her head. She had bright, lively eyes and a ready smile. Her success had given her self-confidence and I don’t believe she could tolerate fools.[39]

Iza’s nephew Ian Coghlan recalled:

She was a very keen student of current affairs, astute, and retained her full faculties right up to her death … and at all times was proverbially generous to a fault.[40]

Iza died of coronary heart disease on 1 July 1946 at the NSW Community Hospital in Moore Park. Despite loyal and lifelong membership of the New South Wales branch of the British Medical Association, and her multiple pioneering achievements in medicine, there was no obituary for her in its official organ, the Medical Journal of Australia.

References

Louella McCarthy Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885-1939, UNSW PhD Thesis, 2001

Notes

[1] Theobald, Marjorie R, Knowing women: origins of women's education in nineteenth-century Australia, (Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 123; Coghlan, TA and Coghlan family and National Library of Australia and Australian Joint Copying Project and State Library of New South Wales. Papers of Sir Timothy A Coghlan [microform]: [M807-814, M828], 1878-1959 & 187

[2] Louella McCarthy, Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885–1939 (PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales), 2001, 34-35

[3] Tyler, Peter J, Humble and Obedient Servants: 1901-1960, (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2006), 23; Ann O’Connell, ‘Ashfield Women Seeking a Voice: Women’s Franchise,’ in C Pratten and Ashfield and District Historical Society, Ashfield at Federation (Ashfield, NSW: Ashfield District Historical Society, 2001), 108

[4] Register of Admission for 1883, Sydney Girls’ High School Archives; Sydney Morning Herald, 14 October 1933, 9

[5] Ann O’Connell, ‘Ashfield Women Seeking a Voice: Women’s Franchise,’ in C Pratten and Ashfield and District Historical Society, Ashfield at Federation (Ashfield, NSW: Ashfield District Historical Society, 2001), 115; Coghlan, TA and Coghlan family and National Library of Australia and Australian Joint Copying Project and State Library of New South Wales. Papers of Sir Timothy A Coghlan [microform]: [M807-814, M828], 1878-1959 1878

[6] Cecil Purser, ‘Early Days of the Medical School,’ Sydney University Medical Journal Jubilee XXVII (September: 1933), 196

[7] The University of Sydney Calendar Archive 1890, http://calendararchive.usyd.edu.au/Calendar/1890/1890.pdf, viewed 2 January 2015

[8] The University of Sydney Calendar Archive 1892, http://calendararchive.usyd.edu.au/Calendar/1892/1892.pdf, viewed 2 January 2015

[9] Geoffrey Sherington and Steve Georgakis, ‘In Union is strength 1890-1919,’ in Sydney University Sport 1852-2007: more than a club, (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2008), 141

[10] AJ Proust, A Companion of the History of Medicine in Australia 1788-1939, (ACT: AJ Proust, 2003), 214

[11] Freeman’s Journal, 22 April 1893. The Bulletin, 15 April 1893

[12] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 April 1893

[13] Eric Hilder, One Hundred and Twenty Years of Medical Registration in New South Wales 1838-1958, compiled from the records of the New South Wales Medical Board by Eric Hilder, (Sydney: n.p., c1959), 106. Iza Coghlan registered with the NSW Medical Board with certificate number 1814 on the same day as her colleague Grace Fairley Robinson; Louella McCarthy, ‘Finding a Space for Women: The British Medical Association and Women Doctors in Australia, 1880-1939’, Medical History, 62 (No. 1), 2018, 97

[14] Louella McCarthy, Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885–1939 (PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales), 2001, 289-90, 333; Marjorie Hutton Neve, ‘This Mad Folly,’ The History of Australia’s Pioneer Women Doctors, (Sydney: Library of Australian History), 142-43, 145. Doctors Dick and Corlis practiced in Elizabeth Street, Sydney

[15] Ethel Turner and Poole, Philippa, (comp.), The Diaries of Ethel Turner, (Sydney: Ure Smith, 1979), 111

[16] National Advocate, 24 June 1893

[17] Louella McCarthy, Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885–1939 (PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales), 2001, 316-18

[18] Referee, 26 December 1894; Australian Town and Country Journal, 14 September 1895; Sydney Morning Herald, 22 September 1897

[19] Lady Doctors, Goulburn Herald, 1 June 1896 p4

[20] Louella McCarthy, Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885–1939 (PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales), 2001, 290, 294. McCarthy suggests that as a ‘surgeon’ Iza may have begun to specialise in the diseases of women at her suburban practice; Sands Directories

[21] Lilith Norman, The Brown and Yellow: Sydney Girls’ High School 1883-1983, (Melbourne, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), 208

[22] Evening News, 26 August1899

[23] The Dawn, 1 August 1900, 20

[24] Marjorie Little, ‘Some Pioneer Women of the University of Sydney’, The Medical Journal of Australia, (13 September: 1958), 343

[25] Marjorie Hutton Neve, ‘This Mad Folly!’ The History of Australia’s Pioneer Women Doctors, (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 131, 141

[26] Louella McCarthy, Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885–1939 (PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales), 2001, 338, 344

[27] Sydney Morning Herald, 3 November 1910

[28] State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales Australia, ‘Returns of the Colony’, Series: NRS 1286, File: Public Service Lists (Blue Books), Microfiche 13 fiche [807-819]

[29] The address of Iza’s Elizabeth Street practice is not listed after 1916 in the New South Wales Medical Board, Register of Practitioners New South Wales, Vol. 1914-25

[30] Louella McCarthy, Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885–1939 . (PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales), 2001, 254-56

[31] State Records Authority of New South Wales, Department of Education, 20/12779, Education Subject Files 1875-1948, Medical Branch 1916

[32] The Shoalhaven News and South Coast Districts, 8 May 1915

[33] Peter J Tyler, ‘Public vs Private Health Care: The School Medical Service in New South Wales’ (paper presented at the 12th Biennial Conference, Australian and New Zealand Society of the History of Medicine, Brisbane, July 2011)

[34] See Dan Hatton at https://rylstonequilt.blogspot.com.au/search/label/COGHLAN%20Dr%20Iza%20Frances%20Josephine, viewed 12 February 2018. The quilt contains more than 900 embroidered names, some of servicemen, and others of people in the Rylstone area of New South Wales. It is held by the Australian War Memorial..

[35] State Records Authority of New South Wales, Department of Education, 20/12786, Education Subject Files 1875-1948, Medical Branch 1926, Dr Edelsten-Pope to Harvey Sutton, Principal Medical Officer Department of Education, 24 November 1925 .

[36] State Records Authority of New South Wales, Department of Education, 20/12786, Education Subject Files 1875-1948, Medical Branch 1926, Harvey Sutton, Principal Medical Officer Department of Education to The Under Secretary, Director of Education, 12 December 1925 and 29 December 1925. Sutton’s letters outline in detail how the school medical and dental service in New South Wales had expanded and altered since its inception..

[37] AJ Proust, A Companion of the History of Medicine in Australia 1788-1939, (ACT: AJ Proust, 2003), 214-15.

[38] The Hornsby Torch, Hornsby Girls’ High School, (Hornsby, NSW: 1934), 20, Hornsby Girls’ High School Archives.

[39] AJ Proust, A Companion of the History of Medicine in Australia 1788-1939, (ACT: AJ Proust, 2003), 215.

[40] Marjorie Hutton Neve, ‘This Mad Folly!’ The History of Australia’s Pioneer Women Doctors, (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 141-42. Iza’s nephew Ian Coghlan gave this appraisal in a letter to Neve.