The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Parramatta's General Hospital

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The General Hospital

[media]The General Hospital is the name given to Parramatta's first two hospitals for convicts. The hospitals were located on Marsden Street overlooking the Parramatta River in an area once called the Hospital Precinct, now known as the Parramatta Justice Precinct. The Tent Hospital was the General Hospital's original incarnation, until November 1792 when it was replaced by a clay brick building. The extremely poor conditions of this second hospital precipitated the construction of The Colonial Hospital which operated on the same site from 1818 and was the last hospital dedicated to convict healthcare in Parramatta.

Pre-contact Aboriginal occupation

Between 10,000 and 22,000 years before European settlement [1] Parramatta was the traditional hunting and fishing grounds of the Darug-speaking Burramatta people. Located on the bank of the Parramatta River, the land of the Parramatta Hospital site would have been used by the Burramatta at least sporadically for fishing and camping purposes. [2]

The tent hospital, 1789–1792

The Tent Hospital, which is believed to have stood to the north of where Jeffery House is now situated, [3] was Parramatta's first hospital, and the third in the colony of New South Wales. It was not literally a tent but was referred to as such because its 'two long sheds' were 'built in the form of a tent, and thatched.' [4] Its construction was hastily completed to cope with the high morbidity rate of convicts who typically worked long hours of hard labour with little or no food and lived in close, unsanitary conditions with almost none of life's necessities. [5]

Even though the Tent Hospital could accommodate 200 people, this quickly proved inadequate as, in addition to injuries caused by corporal punishment in the form of floggings as well as violence between convicts, the convicts' poor diet [6] and living conditions caused a large percentage to fall gravely ill with dysentery and fever, and even to die on the spot where they laboured. Simultaneously, the convict population was rapidly increasing with the arrival of new transport ships and without any progress being made toward the prevention and management of disease. [7] According to Captain Watkin Tench in November 1790, the Tent Hospital was 'most wretched...totally destitute of every conveniency.' [8]

The first surgeon of this hospital was Thomas Arndell who arrived with the First Fleet on the Friendship as an assistant to surgeon John White. Arndell was therefore responsible for the care of First Fleet convicts during the passage from England. John Irving – a surgeon convicted to transportation on the First Fleet's Scarborough [9] and the first convict to be emancipated – was assistant surgeon to Arndell at the Tent Hospital. Prior to Irving's Parramatta appointment, he had been employed in a surgical capacity possibly on the Lady Penrhyn during the passage to Botany Bay, at the hospital in Sydney, and as an assistant surgeon to Dennis Considen on HMS Sirius during its journey to Norfolk Island. Arndell retired in October 1794. [10]

A brick hospital, 1792–1818

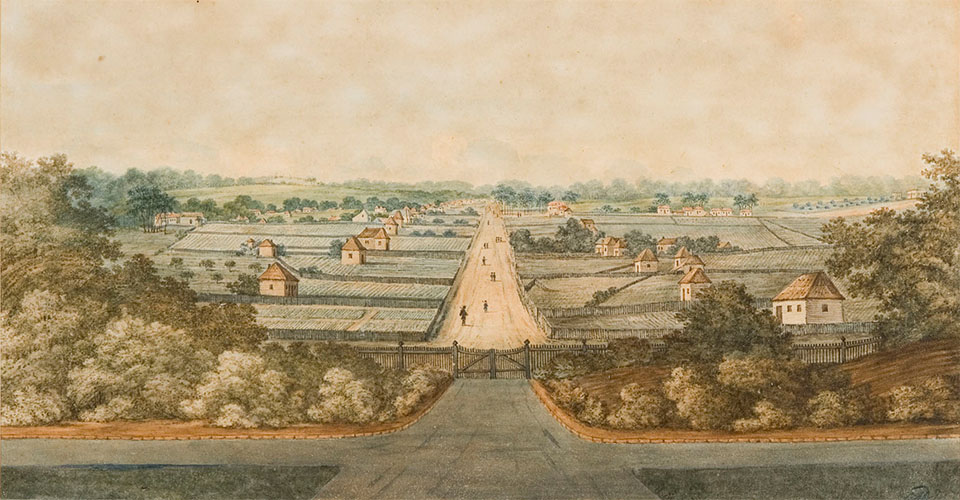

[media]By December 1791 the population of Parramatta exceeded that of Sydney, [11] prompting the construction of what was intended to be a more permanent and commodious hospital befitting its role as the main hospital of the colony.

Foundations for this second hospital, made of locally sourced clay bricks, [12] were laid 100 metres from the riverbank behind the original Tent Hospital in April 1792. The 'brick hospital, consisting of two wards, was finished' by November 1792 and that same month, wrote David Collins, 'the sick were immediately removed to it.' [13]

A plan of the site dating from around 1792, and a drawing by visiting Spanish artist Fernando Brambila dated 1793, indicates there were numerous buildings that comprised the second hospital – as many as nine, including guards and surgeons' houses, which were plastered and whitewashed. [14] The main building was also plastered and whitewashed and measured 80 feet long and 20 feet broad. [15] Based on the 1792 plan, the hospital's two brick wards appear to have been placed a considerable distance apart, potentially indicating that they were used to treat male and female convicts separately. [16] In an attempt to ensure convict patients could 'benefit from air and exercise' during their hospital stay, without 'any improper communication with the other convicts, a space was to be inclosed [sic] and paled in round the hospital.' [17]

Such descriptions give the impression that the second hospital was a vast improvement from the 'wretched' Tent Hospital that Tench had seen in 1790, but the conditions of the brick hospital proved to be extremely poor. Though a stronger building material had been used in the construction of the hospital, limestone was unavailable and this meant the height of buildings was limited to 12 feet (3.7 metres). [18] Another negative consequence of the lack of limestone was serious dilapidation of the structure, which was evident to David Collins who noted as early as 1798 that all the Government buildings of Parramatta 'were so far decayed as to be scarcely able to support their own weight.' [19] Governor Lachlan Macquarie, too, thought it probable that the hospital walls would fall down in 1809 and that any attempts to repair them would prove futile. [20]

The convicts assigned to work in the hospital as overseers, wardsmen, gardeners, woodchoppers, and nurses also had negative consequences for patients. [21] Typically, those assigned to do unpaid work in the hospital were ill-suited to hard labour due to their age and/or their own health issues, while the women who served as nurses did so as a form of punishment for misconduct. The result was 'neglect of duty' and frequent theft in a hospital that was already suffering from a lack of medical supplies. [22]

In a letter to Earl Bathurst in 1818, Reverend Samuel Marsden described the hospital as being 'open night and day for every infamous character to enter; there are no locks or bolts to any of the doors' and the hospital also lacked a room for the deceased. The dead, wrote Marsden, '…lie in the room with the living patients.' There was no lighting, and patients experienced distress over a lack of 'common necessaries...sugar, rice, tea and wine.' Marsden concluded with his characteristic outrage, 'I do not believe that there was ever such a place for want, debaucheries and for every vice as the general hospital at Parramatta.' Assistant Surgeon Major West added that the roof leaked, windows were broken, the wood was rotten, the rationed meat was putrid and, in the absence of a mortuary, the dead bodies had begun to be placed in the passage between the two wards. [23]

Indeed, the hospital's reported disorderly manner of dealing with the deceased in this period is both confirmed and contradicted by the discovery during archaeological excavations carried out on site in 2006 of a shallow circular grave 'immediately north of the southern boundary wall and immediately east of the 1790s storage cellar,' [24] dating from the second hospital era, specifically the late 1790s to early 1800s. The random nature of this single grave containing the remains of two babies on unconsecrated ground is in keeping with contemporary reports about the casual treatment of dead bodies. Conversely, the babies were 'lying side-by-side' with their heads oriented towards the east and the rising sun; a characteristically Christian burial practice. The existence of a somewhat Christian burial on unconsecrated ground for babies who may not have lived long enough to be baptised suggests that at least some care was taken. [25]

Under Governor King, the convict hospitals strictly existed to treat prisoners and convicts assigned to settlers, people of the civil department and other government employees such as the military, all at the governor's cost. The lives of free settlers were, thus, put in jeopardy, and at least one was lost as a result of these stipulations because surgeons either had to treat free settlers without receiving any fee or refuse to provide medical assistance. [26]

At the request of Governor Macquarie, John Watts designed Parramatta's third hospital for convicts, known as 'The Colonial Hospital,' which opened in 1818 on the site of the first two hospitals.

Heritage Courtyard

Parramatta's [media]original hospitals are commemorated in the form of the Heritage Courtyard at 160 Marsden Street. Archaeological remains, artefacts, photographs, maps, sketches and primary source quotations are displayed along with historical information about the people and buildings that were associated with the Parramatta Hospital site, including the 1821 dwelling house, Brislington, which exists today.

References

Anonymous. 'Early News from a New Colony: British Museum Papers'. Historical Records of New South Wales, Series 1, Vol. II, APPENDIX E. Available online: http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1300291h.html. Viewed 7 January 2015.

Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd. Reports relating to the Excavation of the former Parramatta Hospital Site. Marickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, March 2006. Available online: http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/reptpjp.htm, viewed 8 January 2015

David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Vol. 1. London: T Cadell Jnr, and W Davies, 1798. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12565/12565-h/12565-h.htm. Viewed 7 January 2015

Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW). Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital. Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988.

Terry Kass, Carol Liston and John McClymont. Eds. Parramatta: A Past Revealed. Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996.

Notes

[1] 10,000 plus years is the conservative date but use of this land for hunting and fishing could easily date back 15,000 to 22,000 years when taking into account the archaeological evidence of Aboriginal presence discovered in 2004–05 during excavations of 109–113 George Street; the eastern end of the street on which the Parramatta Hospital site is located. According to Casey and Lowe 'Recent archaeological work at the eastern end of George Street indicates the presence of Aboriginal people in Parramatta as extending back 15,000 to 22,000 years BP. The 109–113 George Street site is the oldest known archaeological site revealing Aboriginal presence in the Sydney region indicating the known location of Aboriginal existence prior to stabilisation of post-glacial sea levels c.6000 years ago.' Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Parramatta Children's Court Site: Results of the Archaeological Investigation' (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, 2006), 51, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pcc/pccs3.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015

[2] Dr. Laila Haglund's testing of the Parramatta Children's Court site for potential Aboriginal archaeology unearthed only limited Aboriginal artefact remains. Haglund concluded that 'Aboriginal heritage material was in early colonial times present on and/or in the surface sediments of the site but probably as occasional small scatters' andIt is likely that the area was not intensively used in pre-colonial times or that evidence of earlier, more intensive use had been removed well before this time by natural events such as erosion or floods.' Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Parramatta Children's Court Site: Results of the Archaeological Investigation,' (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, 2006), 51, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pcc/pccs3.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015.Archaeological remains may also have been disturbed by nineteenth and twentieth century occupation and hospital construction activities. Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Results Archaeological Investigation Stage 2c: Parramatta Justice Precinct former Parramatta Hospital Site, (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, September, 2006), 2, 8, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart1.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015; Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Archaeological Excavation: Parramatta Justice Precinct, Former Parramatta Hospital Site, George and Marsden streets, Parramatta, (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, April 2005), 1, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/leaflet2.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015

[3] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Excavation Permit Application: Parramatta Hospital Site, Marsden Street, Parramatta,' (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, March 2005), 49, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/parra/pjphistory.pdf, viewed 7 January 2015

[4] Watkin Tench cited in Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 13; Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Excavation Permit Application: Parramatta Hospital Site, Marsden Street, Parramatta' (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, March, 2005), 17, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/parra/pjphistory.pdf, viewed 7 January 2015

[5] George Thompson in Historical Records of New South Wales, Series 1, Vol. II, APPENDIX E: 'Early News from a New Colony: British Museum Papers,' http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1300291h.html, viewed 7 January 2015; Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 13–4

[6] Terry Kass, Carol Liston and John McClymont (eds), Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 20

[7] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 13–4

[8] Captain Watkin Tench cited in Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 13

[9] John Irving was transferred to the Lady Penhryn on 20 March 1787 before the fleet set sail in mid-May.

[10] Terry Kass, Carol Liston and John McClymont (eds), Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 20; Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 14

[11] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 14; Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Excavation Permit Application: Parramatta Hospital Site, Marsden Street, Parramatta' (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, March 2005), 18, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/parra/pjphistory.pdf, viewed 7 January 2015

[12] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Excavation Permit Application: Parramatta Hospital Site, Marsden Street, Parramatta' (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, March 2005), 17, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/parra/pjphistory.pdf, viewed 7 January 2015

[13] David Collins, 'Chapter XIX,' An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Vol. 1 (London; T Cadell Jnr, and W Davies, 1798). Available online http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12565/12565-h/12565-h.htm#chapter19, viewed 7 January 2015

[14] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Excavation Permit Application: Parramatta Hospital Site, Marsden Street, Parramatta' (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, March 2005), 18–9, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/parra/pjphistory.pdf, viewed 7 January 2015

[15] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 14

[16] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Excavation Permit Application: Parramatta Hospital Site, Marsden Street, Parramatta' (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, March 2005), 18, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/parra/pjphistory.pdf, viewed 7 January 2015

[17] David Collins, 'Chapter XIX,' An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Vol. 1 (London; T Cadell Jnr, and W Davies, 1798), available online: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12565/12565-h/12565-h.htm#chapter19, viewed 7 January 2015

[18] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 14

[19] David Collins, 'Chapter VIII,' An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Vol. 1 (London; T Cadell Jnr, and W Davies, 1798), available online: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12565/12565-h/12565-h.htm#chapter19, viewed 7 January 2015

[20] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 14

[21] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 14–5

[22] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 14–5

[23] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 18

[24] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Excavation Report, Stage 2c Part 1 Final' (September 2006), 14 http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart1.pdf, viewed 19 March 2015

[25] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Excavation Report, Stage 2c Part 1 Final' (September 2006) 14-16 For an image of the grave and skeletons, see page 16. http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart1.pdf, viewed 19 March 2015

[26] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 15