The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Brislington

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Brislington

Brislington, Parramatta's [media]oldest existing dwelling house, was built by convicts for a pardoned convict around 1821 on the site of Burramattagal hunting grounds. The house stands on the corner of George and Marsden streets in the heart of what is now Parramatta's Justice Precinct, formerly known as the Hospital Precinct. The precinct's long history of health care dates back to Parramatta's first hospital [1] in 1789. Brislington served as the Brown family's residence and medical practice from 1857 to 1949 when it became Parramatta District Hospital's Nurses' Home until the early 1970s. It has been the Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum since 1983.

Aboriginal occupation

Between 10,000 and 22,000 years before European settlement [2] Parramatta was the traditional hunting and fishing grounds of the Darug-speaking Burramatta people. Being so close to the Parramatta River, the land on which Brislington stands would have been used at least sporadically for fishing and camping purposes. [3]

Convict hut, 1790–c1821

[media]Like a considerable amount of the surrounding land in 1790, the allotment (Lot 98) on which Brislington was later erected, featured a much humbler abode in the form of a convict hut and an associated outbuilding. [4] The remains of some of the huts from this period of convict occupation have been excavated. [5] By 1792, Lots 98 to 103 along George Street, [6] the river and present-day Marsden Street, [7] formed the boundaries of Parramatta's newly built second hospital. Timothy Hollister, an ex-convict turned Government Overseer and master of two convicts of his own, leased Lot 98 from 1804.

Hodges's house, c1821–1825

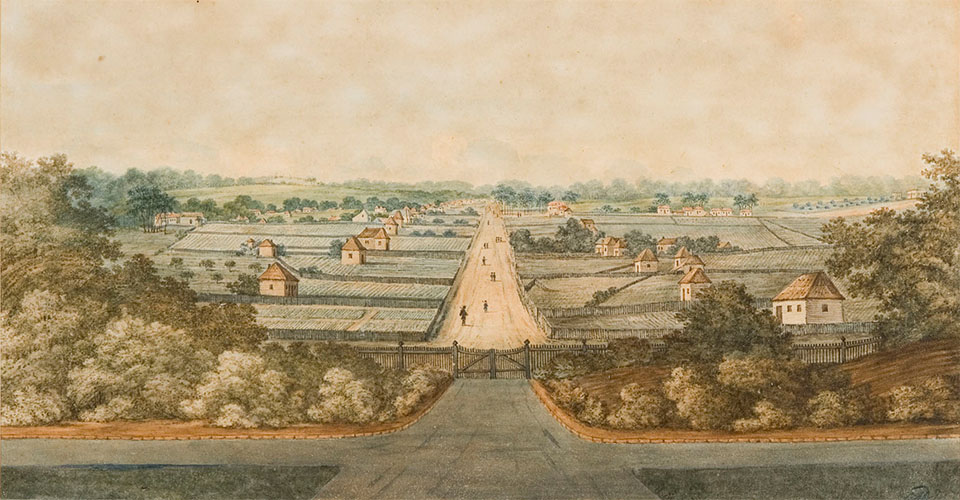

Sometime [media]before 1819, Hollister sold the grant to John Hodges who was an emancipist, keeper of a 'disorderly house,' gambler, sometimes-licenced publican and frequent 'sly grog' trader. [8] Hodges reportedly won £1,000 in gold in a card game at James Larra's Freemasons’ Arms, which at the time was located across the road from Lot 98 on the present site of the Parramatta Court House. [9] He used his winnings to pay for the construction of the townhouse that is now called Brislington. [10]

Hodges's two-storey Colonial Georgian townhouse [media]features red brick laid in Flemish bond and a decorative diamond pattern in contrasting burnt brick on the exterior of the back wall. It is commonly believed Hodges requested the convict bricklayers to include this diamond pattern as a means of commemorating his winning card – the six or eight of diamonds. [11] In 1825, the property contained 'four rooms on each floor with a variety of outhouses, consisting of kitchen and pantry, two servant's bedrooms, a four-stall stable and coach-house' [12] and a cellar. The 'near one-and-a-quarter acre' property also boasted 'one of the first wells of water in the town,' [13] thus one of the first five wells dug in Australia, and a garden including the existing Port Jackson fig tree ( Ficus rubiginosa) in the front garden, which is the oldest tree on the Parramatta Hospital [media]site.

Hodges, who may have used the house as the Anchor & Hope Inn upon being granted another liquor licence, [14] noted that the property was 'most eligibl[e] for business' when he advertised its sale along with his 100-acre (approximately 40.5 hectares) farm at Seven Hills in April 1825. [15] The house does not appear to have been sold, however, until January 1844. This was a forced sale because in addition to the townhouse's previously mentioned qualities, its kitchen fireplace also featured a large stone slab that light-fingered Hodges had stolen. The slab was intended for the mortuary which was under construction at the Colonial Hospital behind Hodges's property at the time. Hodges and his servant Thomas Lynch were convicted for this crime and imprisoned for twelve months.

Doctor's residence and medical practice, 1857–1949

[media]Following the 1844 sale, the property had many different owners including nineteenth-century notables such as George Alfred Lloyd and Sydney solicitor, politician, and philanthropist Sir George Wigram Allen. In 1852 the surgeon of what was then known as Parramatta District Hospital, Dr Thomas Robertson, began residing at the property and commenced its long, direct association with Parramatta's health care services.

[media]In 1857 Dr Walter Brown rented the house and named it Brislington, after the town in Bristol, England where he was born in 1821 – the same year the construction of Brislington was completed. Dr Brown lived in Brislington house, raising his family there, and establishing his medical practice. For the next 92 years spanning three generations (Walter Brown, his son Walter Sigismund Brown, and grandson Keith Sigismund Macarthur Brown), Brislington remained the family residence and medical practice. [16]

Nurses' home, 1949–early 1970s

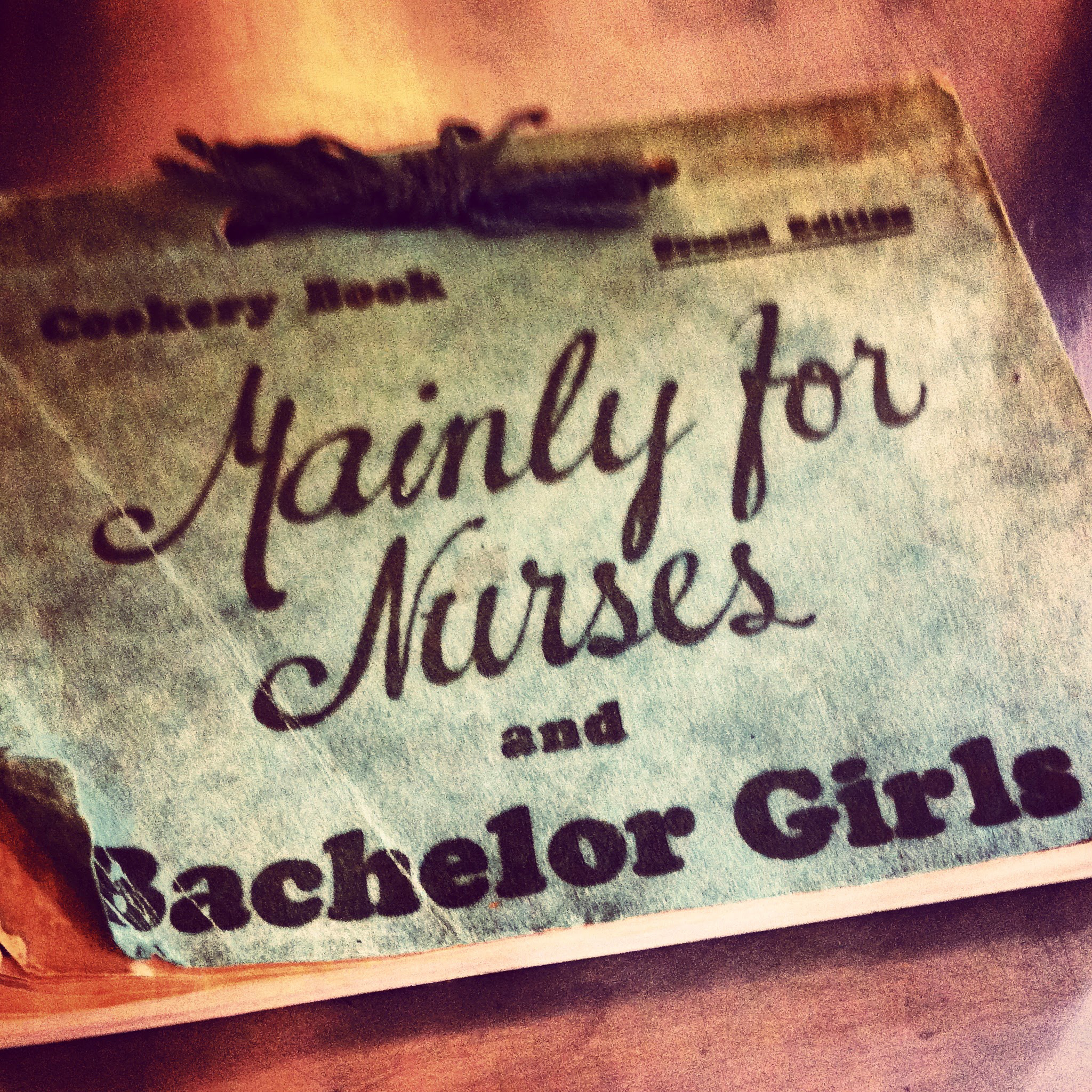

[media]During World War I Brislington was used as temporary nurses' accommodation while discussions commenced regarding the construction of a permanent nurses' home. The Government paid the rent of thirty-five shillings per week from September 1915 for the nurses who stayed there. In October 1920, however, Dr Brown ended this arrangement, stipulating that he needed Brislington by the end of that year. No purpose-built nurses' accommodation had even been settled, let alone constructed, at this stage. It was February 1925 before Kearney House was opened as the nurses' home. [17]

[media]By 1949 Kearney House was inadequate so Parramatta District Hospital again used Brislington as accommodation for its nurses. By the early 1960s, however, the building was suffering from 'termite damage and general deterioration', which raised the possibility of demolishing the rare, historically significant building to make way for a new Diagnostic Services Building. [18] However, the National Trust classified Brislington as highly significant and recommended its restoration in 1968. [19]

Brislington medical and nursing museum, 1983–present

The State Planning Authority, the National Trust and Parramatta Historical Society first proposed that Brislington become an historical museum in July 1973. [20] It was just over a decade before the plans for a museum at Brislington actually came to fruition, following 'Medicine: Past, Present and Future', a display made for Parramatta Council's Foundation Week celebrations.

[media]The Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum covers the history of Brislington itself, as well as the history of Parramatta District Hospital and the broader history of healthcare. Retired nurses belonging to the Parramatta District Hospital Graduate Nurses Association volunteer their time to maintain the museum and provide guided tours of Brislington's rooms including 'The Colonial Room,' 'The Ward,' 'The Nurses' Room' and 'The Operating Theatre'. These rooms are filled with artefacts from the medical profession and set up the way they would have been in particular eras of the Hospital's history.

In December 2013, the Parramatta Advertiser published an article stating that the State Government, needing to raise funds for health infrastructure, were strongly considering the sale of Brislington and nearby heritage-listed Jeffery House, which still employs almost 200 staff and provides numerous health services. The announcement prompted volunteers of Brislington House to lead a campaign to save the rare and historically significant building from being sold. [21]

References

Bartok, Di. 'Parramatta's Oldest Surviving House May Be Put Under the Hammer'.” Parramatta Advertiser, December 18, 2013.

Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum. 'Save Brislington Medical and Nursing museum in Parramatta from the NSW Government.' https://www.change.org/p/save-brislington-medical-and-nursing-museum-in-parramatta-from-the-nsw-government. Viewed 5 January 2015.

Brislington Medical and Nursing Committee. www.brislington.net. Viewed 5 January 2015.

Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum Committee, Brislington 1821. Parramatta: Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum, 2004.

Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW). Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital. Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988.

Kass, Terry, Carol Liston, and John McClymont eds. Parramatta: A Past Revealed. Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996.

Office of Environment and Heritage, 'Parramatta District Hospital – Brislington and Landscape.' http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5051397. Viewed 5 January 2015.

Notes

[1] Parramatta's first hospital was the third in the colony overall.

[2] 10,000 plus years is the conservative date but use of this land for hunting and fishing could easily date back 15,000 to 22,000 years when taking into account the archaeological evidence of Aboriginal presence discovered in 2004–05 during excavations of 109–113 George Street, the eastern end of the street on which Brislington is located. According to Casey and Lowe 'Recent archaeological work at the eastern end of George Street indicates the presence of Aboriginal people in Parramatta as extending back 15,000 to 22,000 years BP. The 109–113 George Street site is the oldest known archaeological site revealing Aboriginal presence in the Sydney region indicating the known location of Aboriginal existence prior to stabilisation of post-glacial sea levels c.6000 years ago.' Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Parramatta Children's Court Site: Results of the Archaeological Investigation' (Sydney: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, 2006), 51. http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pcc/pccs3.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015

[3] Dr Laila Haglund's testing of the Parramatta Children's Court site for potential Aboriginal archaeology unearthed only limited Aboriginal artefact remains. Haglund concluded that 'Aboriginal heritage material was in early colonial times present on and/or in the surface sediments of the site but probably as occasional small scatters' and 'It is likely that the area was not intensively used in pre-colonial times or that evidence of earlier, more intensive use had been removed well before this time by natural events such as erosion or floods.' Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Parramatta Children's Court Site: Results of the Archaeological Investigation,' (Sydney: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, 2006), 51. http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pcc/pccs3.pdf viewed 6 January 2015. Archaeological remains may also have been disturbed by nineteenth and twentieth century occupation and hospital construction activities. Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Results Archaeological Investigation Stage 2c: Parramatta Justice Precinct former Parramatta Hospital Site cnr Marsden and George Streets, Parramatta,' (paper prepared for Multiplex, Sydney, September, 2006) 2, 8. http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart1.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015; Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, 'Archaeological Excavation: Parramatta Justice Precinct, Former Parramatta Hospital Site, George and Marsden Streets, Parramatta' (Sydney: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, April 2005), 1 http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/leaflet2.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015

[4] Potential location of the hut was identified by Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd Archaeology and Heritage as being to the west of Brislington within Lot 98. The hut was located using the 1823 plan, which according to Casey and Lowe proved to be the most accurate for other sites already excavated. Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Parramatta Hospital Site Excavation Permit Application,' (Sydney: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, March 2005) 51, 60, 66–7. http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/parra/pjphistory.pdf viewed 5 January 2015; Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Results Archaeological Investigation Stage 2c: Parramatta Justice Precinct former Parramatta Hospital Site' (Sydney: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, September, 2006), i–ii. http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart1.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015

[5] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, Parramatta Hospital Site Excavation Permit Application' (Sydney: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, March 2005) 51–2, 60, 66–7, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/parra/pjphistory.pdf, viewed 5 January 2015

[6] George Street was known as High Street until 1811 when Governor Macquarie regularised the streets and renamed them to honour the king and colonial elites. High Street extended into present-day Parramatta Park.

[7] Present-day Marsden Street was 'Hospital Lane' in this early colonial period.

[8] Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum Committee, 'Brislington 1821,' (Parramatta: Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum, 2004), 2; Terry Kass, Carol Liston and John McClymont (eds), Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 78

[9] With the building of the Parramatta Court House, the building on the corner diagonally across from Brislington became the Woolpack Inn.

[10] Terry Kass, Carol Liston and John McClymont (eds), Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 78

[11] 'Parramatta District Hospital – Brislington and Landscape,' State Heritage Register, Heritage Council of NSW supported by the Heritage Division of the Office of Environmentand Heritage website, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5051397, viewed 5 January 2015; Terry Kass, Carol Liston and John McClymont (eds), Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996),78

[12] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803–1842), Thursday 7 April, 1825, 4

[13] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803–1842), Thursday 7 April 1825, 4

[14] 'Parramatta District Hospital – Brislington and Landscape,' State Heritage Register, Heritage Council of NSW supported by the Heritage Division of the Office of Environment and Heritage, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5051397, viewed 5 January 2015; Terry Kass, Carol Liston and John McClymont (eds), Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 78

[15] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803–1842), Thursday 7 April 1825, 4

[16] Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum Committee, 'Brislington 1821' (Parramatta: Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum, 2004), 8–9

[17] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 52, 54, 66

[18] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988),70, 78

[19] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW) Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 73; Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum Committee, 'Brislington 1821' (Parramatta: Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum, 2004), 10

[20] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW) Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 77

[21] Di Bartok, 'Parramatta's Oldest Surviving House May Be Put Under the Hammer,' Parramatta Advertiser, December 18, 2013, http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/parramatta/parramattas-oldest-surviving-house-may-be-put-under-the-hammer/story-fngr8huy-1226785567973?nk=332a156eac41d9810b2a8f971d9fa18c, viewed 5 January 2015

.