The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Lockleys Pylon

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Lockleys Pylon

[media]When I was first invited to take a walk to Lockleys Pylon my response was something like 'A pylon? What's so appealing about that?' Well, I was told, it's not really a pylon and the walk there is virtually flat. I had moved to Katoomba because I was pregnant, to live with my child's father, but I was struggling with the steep ascents and descents that characterize the majority of Blue Mountains walks. My struggles with the landscape were not merely physical. Having grown up in Tasmania under dolerite mountains, watching the sky fade into the sea, I was unsettled by the inversions of the Blue Mountains, which are not mountains at all but a series of gaudy cliffs and ridgetop townships, where people look down instead up. I did not know then that looking down from Lockleys Pylon would help me find the stories I needed to settle myself here.

A brief guide to Lockleys Pylon

Firstly, let me tell you that Lockleys Pylon is in Darug country but there are sites of significance to the Gundungurra and Wiradjuri close by. Bushwalking guides rate it a medium, relatively flat walk, of about 7km return that takes about three hours from a car park 7 kilometres north of Leura on the rocky dirt of Mount Hay Road. [1]

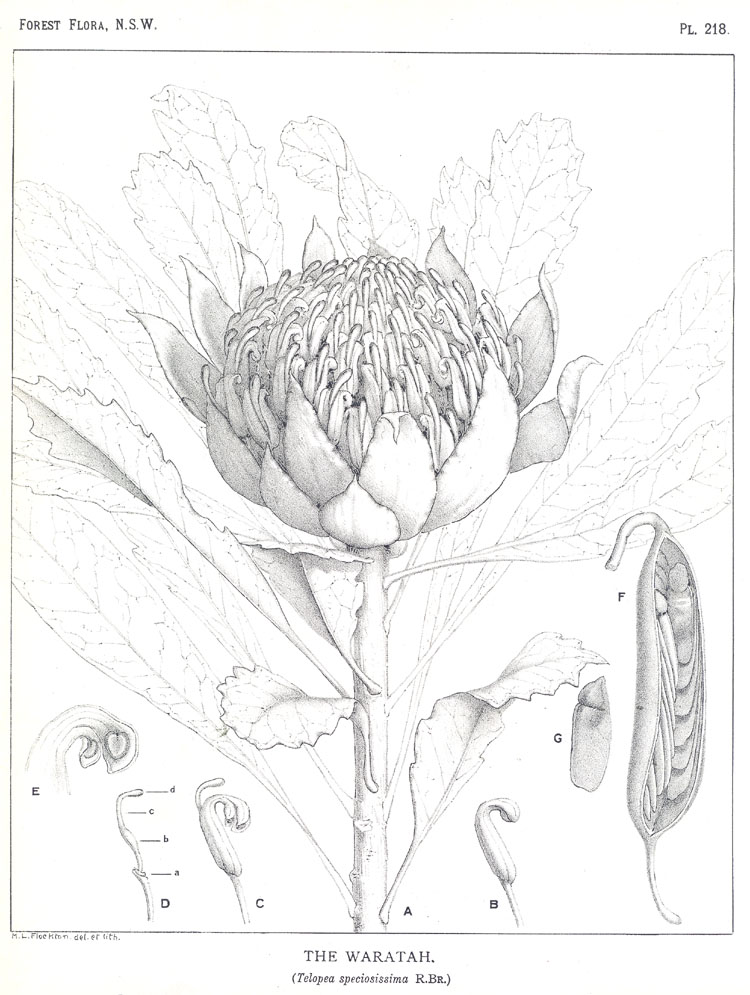

The walk to the pylon is a dry path that wends its way through what is mostly heathland punctuated with low forest and terraced with basalt. The heath looks like an olive carpet until you get close, when you discover it is filled with grasses and flowers. Wherever you look, at any time of year, you can see the stars of miniature flannel flowers (Actinotus minor) with their tiny petals, feathered like cats' tongues. Their languid larger cousins, (Actinotus helianthi) flower in the summer, as does the pink flannel flower (Actinotus forsythia) although [media]it will only flower after a bushfire and I am still waiting for the privilege of seeing one. There are always yellow and purple orchids, mauve fringe lilies, blue lilies, pea flowers, heath blossoms, curly old man's beard (Caustis flexuosa) and dianella. Grass trees (Xanthorrhea spp) burst upward and outward, swirling the inferior grasses around them into bird's nests. Along the forested sections of the track there are mountain devils (Lambertia formosa), drumsticks (Isopogon spp), cone bushes (Petrophile spp), yellow geebungs (Persoonia spp) and all shades of grevillea, as well as the architectural grandeur of old man banksias, the flaming beacons of waratah (Telopea speciosissima) and acacia and eucalyptus trees.

The heath owes its abundance to the peat and hanging swamps that hold the water in suspension above the sandstone, although eventually that water must leach into the gullies and pour out, making waterfalls that wet the cliffs below and feed ferns and sundews. Once I saw a rainbow in the mist from the Fortress Creek falls, its end suspended in the blue air above the valley below, where no one could reach it.

Naming Lockleys Pylon

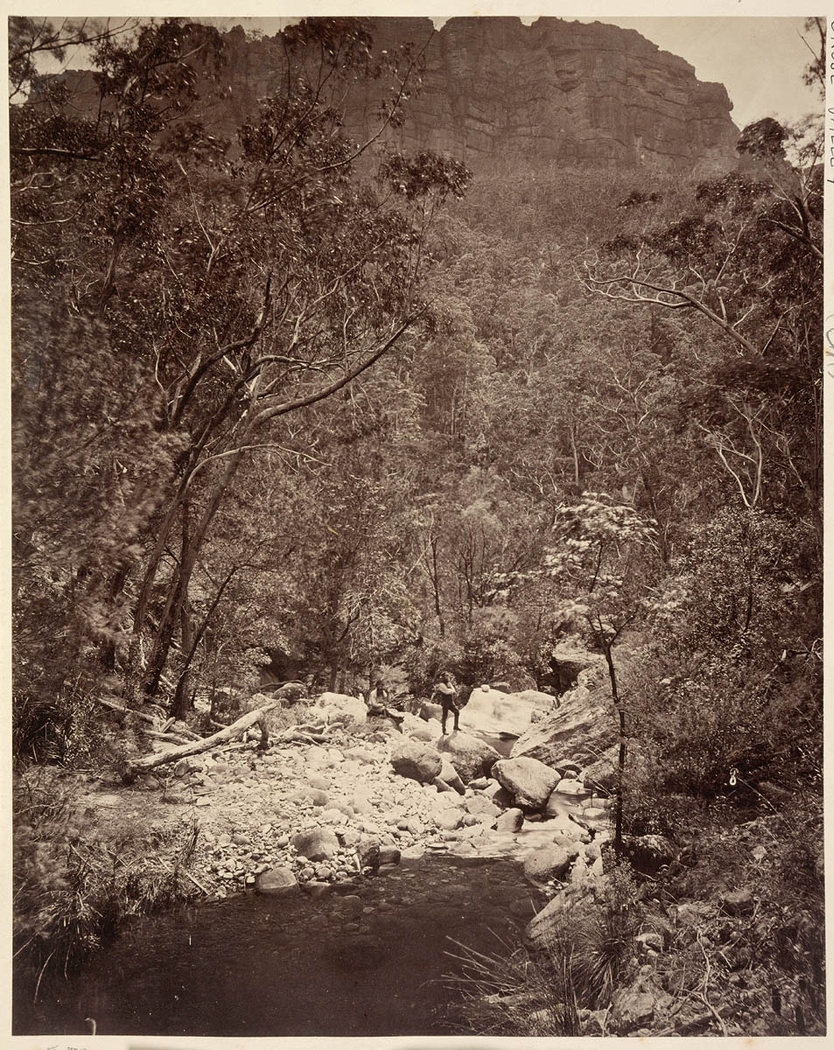

[media]The pylon itself is a bulge at the top of Du Faur Buttress, 600 metres above the floor of the Grose Valley. The 360-degree views sweep to the Illawarra and Sydney, mounts Hay, Banks and Tomah, the Darling Causeway, Hat Hill, Govetts Leap and the Fortress Ridge. It is so quiet out there – there is no sound of road or rail and rarely anyone else on the path, just birdsong and the lazy buzzing of insects. The Grose Valley stretches out beneath, walled by vertiginous cliffs. From the pylon a path, probably used by Aboriginal people before settlement, plunges down the face of the buttress into the iconic Blue Gum Forest.

Although the easiest access to Lockleys Pylon is from the Hay Plain, I always assumed its name was linked to the exploration of the difficult terrain of the Grose Valley. The first person to travel the length of the Grose was Edwin Barton, in 1858, at the head of a party of Royal Engineers (sappers) investigating routes for the Great Western Railway. [2] Robert Hunt, a chemist with the Sydney Mint, visited the sappers twice with a wet plate camera, taking the first images of Burra Korain and the Blue Gum Forest. [3] The sappers' path was used by cattleman Ben Carver who built illegal stockyards before obtaining a conditional purchase lease over 40 acres (10 hectares) on the other side of the river from the Blue Gum Forest that was later acquired by the Hordern family. [4]

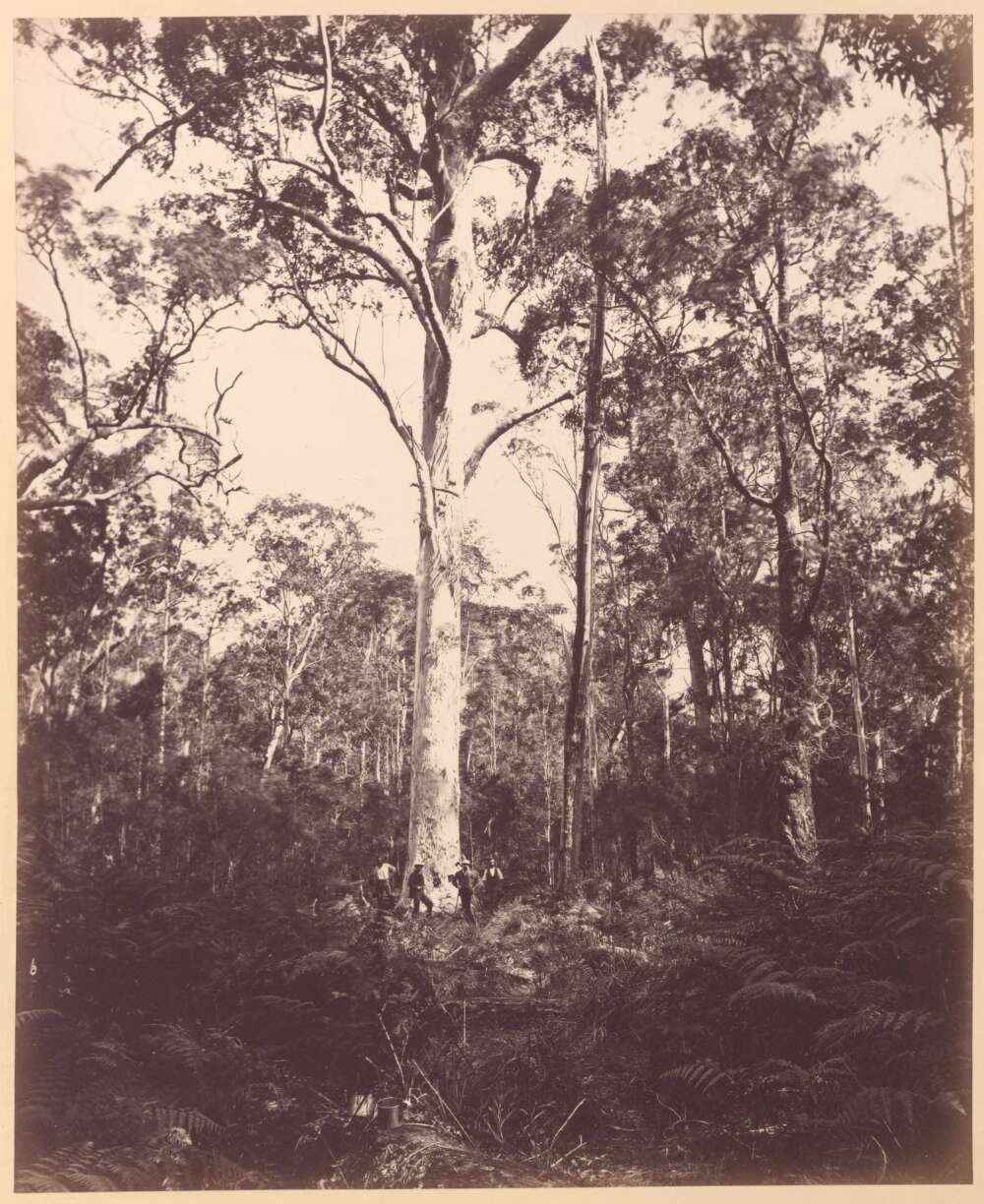

Frederick Ecclestone Du Faur[media] also followed the sappers' path. In 1875, when he was chief draughtsman in the Office of the Occupation of Crown Lands in Sydney and a member of the Academy of Art, Du Faur hired photographer Joseph Bischoff and wilderness painter William Piguenit and set up artists' camps in the Grose Valley. Du Faur hoped Bischoff would capture picturesque landscapes of the sort that inspired tourists to visit Yosemite but the hazy light led to disappointing results. [5] Nevertheless, Du Faur's passion for the site proved crucial, for in his day job he contributed to the government's decision to set the Blue Gum Forest aside as a reserve. [6] It became a haunt for bushwalkers.

Blue gums and Redgum

[media]At Easter in 1931 a group of bushwalkers from the Mountain Trails Club and the Sydney Bush Walkers, led by Alan Rigby, were camped in the Blue Gum Forest when they were surprised by a Bilpin farmer, Clarrie Hungerford, who told them he had leased it and intended to clear it to plant walnuts. The walkers' panic at this prospect fed into Myles Dunphy's efforts to establish a national park in the Blue Mountains and the Blue Gum Forest Committee was formed with the intention of raising funds to purchase the land.

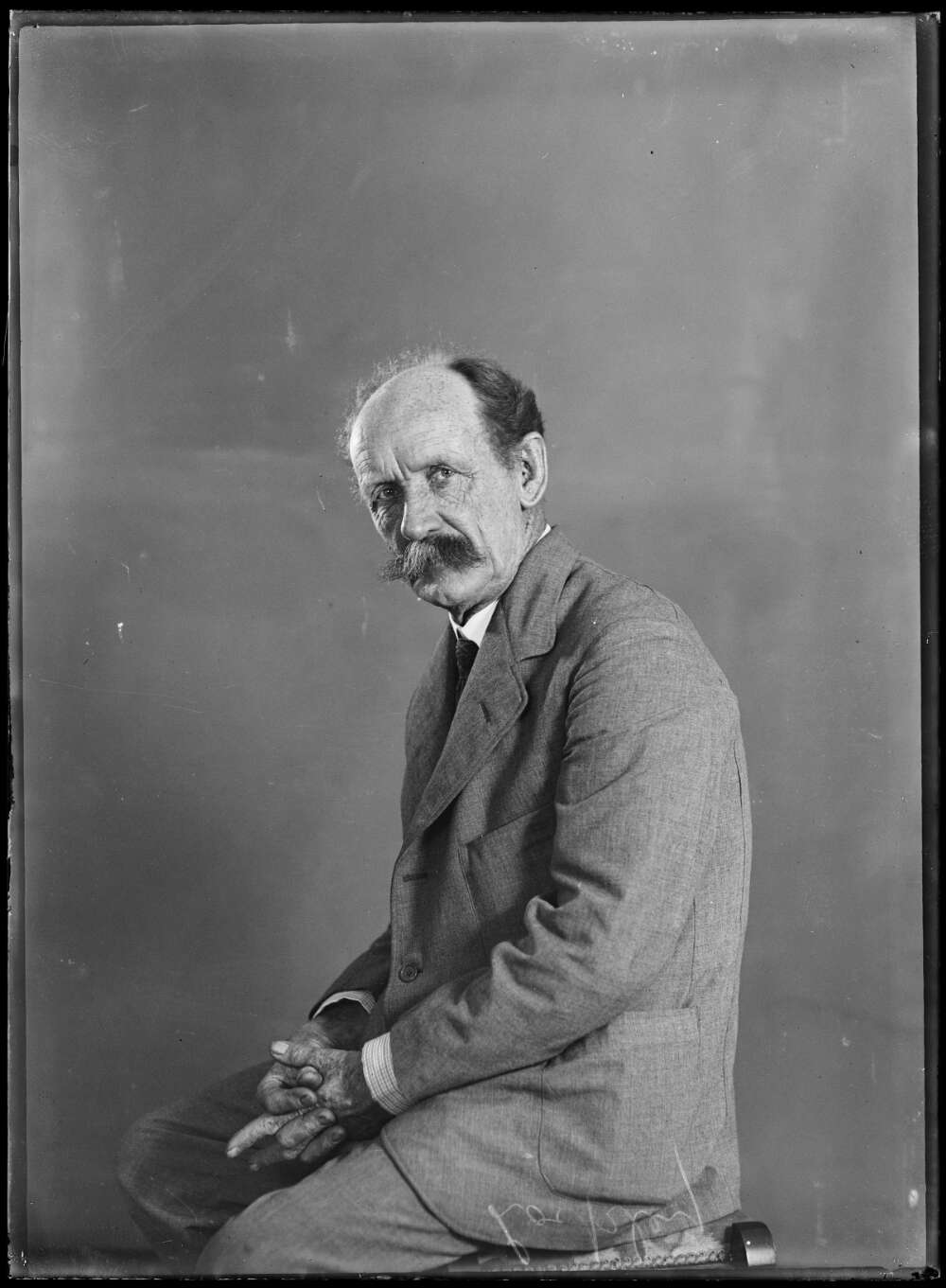

Campaigns require publicity so on 15 November 1931 Myles Dunphy and the committee took The Sydney Morning Herald gardening columnist [media]and conservationist, JG 'Redgum' Lockley, into the Blue Gum forest. Lockley, who was nearly 70, admired the great rocky 'pylon' on top of Du Faur Head and the conservationists told him they would name it after him. For the rest of his life Lockley would joke 'Well, I've done little, but the others haven't got a pylon!' [7]

The money was raised and the Blue Gum Forest was gazetted as a public recreation reserve in September 1932. [8] The Blue Mountains National Park was declared in 1959 and the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area was proclaimed in November 2000. So, to look over the edge of Lockleys Pylon is to look into the history of the conservation movement. However, it’s the more recent history that has helped me orient myself in the Blue Mountains.

Stealth

In 2004, after a series of devastating fires over the Hay Plain, the American producers of a movie about an anthropomorphized fighter jet called Stealth received approval from the government to use the fire-blasted heath at Butterbox Point, on the Lockleys Pylon side of Mt Hay, as a backdrop for their film. The locals were having none of it.

By this time I had become involved in local politics and the writers' circle around Varuna. I knew the local member, Bob Debus, the Labor Minister for the Environment and the Arts and responsible for both elements of the conflict, as well as many of the people who formed a blockade on Mt Hay Road, including the anthropologist Dianne Johnson. [9] One of the most eminent protestors was Mick Dark, the son of Eleanor and Eric Dark, a committed conservationist and the benefactor of Varuna. Mick had rambled across the Mount Hay area since he was tiny and his family retreat, Dark's Cave, is on the western side of Fortress Ridge. [10]

Mick was, for the first time in his life, arrested, along with several others. However Katoomba and Leura are small, politically conscious towns. The magistrate, George Zdenkowski, was married to Di Johnson, and in his May 2004 judgement defended the right of the protestors to act to prevent something they saw as deleterious. [11] Mick's charges were dismissed but he remained furious with the government and threatened to refuse an award he was about to receive from the premier for his contribution to literature. This was exquisitely embarrassing for Bob Debus, who endured a long NSW Premiers Literary Awards dinner wondering if Mick would carry out his threat.

I was at that dinner and enjoyed the sense that my personal relationships, writing life and politics had come together for me in the mountains. I later joined the Labor Party, won a fellowship to Varuna named for Dr Eric Dark, and did some work on Dianne Johnson's book about the Blue Mountains Aboriginal community, Sacred Waters. [12] Those connections were, and still are, vital to me, although Dianne died in May 2012 and Mick died in July 2015. Bob Debus joined Varuna's board and at Mick's memorial service we laughed about Mick's arrest and that dinner. Whenever I walk on the Hay Plain I think about Mick and Dianne and their gifts of passion, courage, friendship and story.

Walking towards home

In the sixteen years I've lived in the Blue Mountains I've walked to Lockleys Pylon many times, with friends and partners and kids. My son first walked it himself at four, falling asleep at the pylon from the effort. One Anzac Day holiday when he was seven and I was newly single we headed out there but the wind blasting the silvered heath knocked us flat. I had to lie on him to keep him from flying away.

With my last lover, when love was new, we sat at the pylon, giggling on champagne, bare skin in the warm air. A year later, on a November afternoon, we did the classic trek from Perry's Lookdown at Blackheath, down to the Blue Gum Forest, and up the Du Faur Buttress. The sun on the rock face made me dizzy and I stripped to my knickers as I climbed but I am glad I've done it, at least once.

Lockley's Pylon has also become the place I go to when I need to heal. The weekend after the World Trade Centre was destroyed I took my son out to the pylon, to replace images of hijacked planes and death with the timelessness of that view. I've walked it to recover from childbirth and miscarriages. Last year, when love was gone, I returned to Lockleys. I lay in sandstone cradles, catching the golden light of the late afternoon, and came back in the dark by the light of my phone, feeling safe, and settled.

Every visit to Lockleys Pylon has softened this landscape for me, and the path is now threaded with stories, of me and of the Blue Mountains. It's not quite home here, but it is something close to it.

References

MacQueen, Andy. Back from the Brink: Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Wilderness. 2nd ed. Wentworth Falls: Andy MacQueen, 2007

Lockleys Pylon walking track: Blue Mountains National Park. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service website. http://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/things-to-do/walking-tracks/lockleys-pylon-walking-track

Newton, Gael. Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839–1988. Canberra: Australian National Gallery, 1988

Snowden, Catherine. 'The Take-Away Image: Photographing the Blue Mountains in the Nineteenth Century' in Peter Stanbury (ed), The Blue Mountains: Grand Adventure for All. Leura: Second Back Row Press Ltd and The Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, 1988, 133–156

Notes

[1] Lockleys Pylon walking track: Blue Mountains National Park, NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service website, http://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/things-to-do/walking-tracks/lockleys-pylon-walking-track, viewed 2 November 2015; Lockleys Pylon, Wild Walks website, http://www.wildwalks.com/bushwalking-and-hiking-in-nsw/blue-mountains-leura/lockleys-pylon.html, viewed 2 November 2015; Lockley Pylon, Bushwalking NSW website, http://bushwalkingnsw.com/walk.php?nid=723, viewed 2 November 2015

[2] Andy MacQueen, Back from the Brink: Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Wilderness, 2nd ed (Wentworth Falls: Andy MacQueen, 2007), 53–56; Mark Langdon, Conquering the Blue Mountains (Matraville: Eveleigh Press, 2006), 7–10

[3] Catherine Snowden, 'The Take-Away Image: Photographing the Blue Mountains in the Nineteenth Century', in Peter Stanbury (ed), The Blue Mountains: Grand Adventure for All (Leura: Second Back Row Press Ltd and The Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, 1988), 133–156

[4] Andy MacQueen, Back from the Brink: Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Wilderness, 2nd ed (Wentworth Falls: Andy MacQueen, 2007), 90

[5] Gael Newton, Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839–1988, Canberra: Australian National Gallery, 1988, http://photo-web.com.au/ShadesofLight/06-expedition.htm, viewed 2 November 2015; Catherine Snowden, 'The Take-Away Image: Photographing the Blue Mountains in the Nineteenth Century', in Peter Stanbury (ed), The Blue Mountains: Grand Adventure for All (Leura: Second Back Row Press Ltd and The Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, 1988), 133–156

[6] Andy MacQueen, Back from the Brink: Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Wilderness, 2nd ed (Wentworth Falls: Andy MacQueen, 2007), 241–242

[7] Andy MacQueen, Back from the Brink: Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Wilderness, 2nd ed (Wentworth Falls: Andy MacQueen, 2007), 255–256

[8] 'Some events in order of time', The Katoomba Daily, 24 Aug 1934, 7, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article193893649, viewed 29 November 2015

[9] Robyn Mosman, 'Stealth Movie Story', Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Experience, http://www.worldheritage.org.au/stories/stealth-movie-story/, viewed 29 November 2015

[10] Andy MacQueen, Back from the Brink: Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Wilderness, 2nd ed (Wentworth Falls: Andy MacQueen, 2007), 34

[11] Blue Mountains Conservation Society Past Campaigns, Stealth, http://www.bluemountains.org.au/pastcampaigns/stealth/arrestees.html, viewed 26 November 2015

[12] Dianne D Johnson, Sacred Waters: The Story of the Blue Mountains Gully Traditional Owners (Broadway: Halstead Press, 2007)

.