The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Parramatta Female Factory

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Parramatta Female Factory

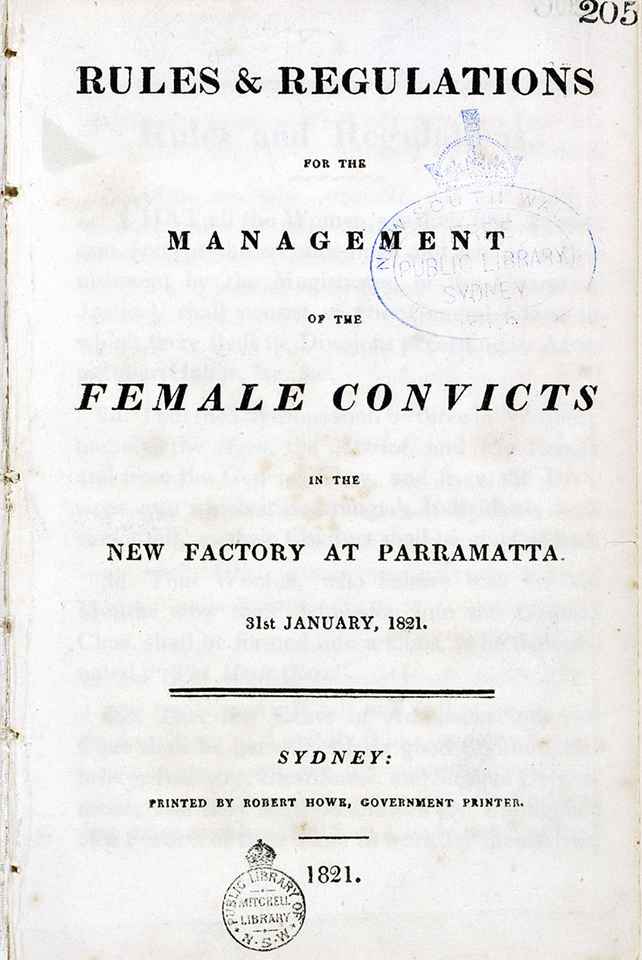

[media]The Parramatta Female Factory is the largest and oldest surviving convict women's site in Australia. Built by convict men between 1818 and 1821, this multi-purpose institution served the colony of New South Wales until 1848 as a refuge for women, children, elderly and sick women; a marriage bureau; a place of assignment and moral reform; a penitentiary; a women's hospital for the convicted as well as the free; and a workhouse all rolled into one. [1] . Although this was the second Female Factory established at Parramatta, it was the first purpose built factory and the one on which all other Australian female factories were based. It is located approximately three kilometres north of the Parramatta CBD on 56 acres (approximately 23 hectares) of land currently occupied by Cumberland Hospital. The factory's surviving buildings are found off Greenup Drive and Fleet Street, North Parramatta in the Fleet Street Heritage Precinct, just five minutes walking distance from Parramatta Gaol with which it shares a long history.

'The factory above the gaol': The first Female Factory, c1802–1821

[media]The stories of both the factory and the gaol began elsewhere at what is now known as Prince Alfred Park but was once the site of the colony's first two gaols, court-ordered punishments, and executions. The second floor of the second gaol built at that location – a two-storey stone structure consisting of two, 80 by 20 foot (5.5 by 6 metre) rooms – was allocated to female convicts and was called 'The factory above the gaol'. It was a wool and linen factory where women worked by day and it served as their refuge by night. [media]From its inception, then, the factory was intended to be a place where women who had not been immediately assigned to masters upon arrival in New South Wales were gainfully employed in tasks that were beneficial to the colony, and where corrupting influences could be kept at bay. In reality, this space was inadequate for achieving all of its aims as the majority of factory women could not find shelter there. Nevertheless, a larger space was not forthcoming until 1817 when Governor Macquarie started arranging the design and construction of a new purpose-built barracks for female convicts. [2]

The second Female Factory, 1 February 1821–1848

[media]Convict and colonial architect, Francis Greenway, designed the new factory to be built on four acres (1.6 hectares) of land at its current location on the left bank of the Parramatta River. On 4 May 1818, Governor Macquarie laid the foundation stone of the second Female Factory, and after almost three years of construction by contractors William Watkins and Isaac Peyton, Chief Engineer Major George Druitt, and the labour of countless male convict stonemasons, the new Female Factory opened its doors to inmates on 1 February 1821 [3]. Governor Macquarie [media]described the new factory as,

A Large Commodious handsome stone built Barrack and Factory, three storeys high, with Wings of one storey each for the accommodation and residence of 300 Female Convicts, with all the requisite Out-offices including Carding, Weaving and Loom Rooms, Work-Shops, Stores for Wool, Flax, etc, etc.; Quarters for the Superintendent, and also a large Kitchen Garden for the use of the Female Convicts, and Bleaching Ground for Bleaching the Cloth and Linen Manufactured; the whole of the Buildings and said Grounds, consisting of about Four acres, being enclosed with a high Stone Wall and Moat or Wet Ditch. [4]

But the nine-foot (2.7 metre) factory walls did not keep out the vices that had plagued convict women outside. Indeed, many contemporaries, including Governor Hunter and Roger Therry, claimed that, far from benefiting public morality, the factory's concentration of large numbers of women who had reportedly already experienced the worst of human depravity made them the most corrupt members of colonial society; worse, even, than the men. [5]

[media]With a much larger group of women to manage and control at this new factory, a class system was introduced. In the first five years this was a two-class system but with the addition of more sleeping quarters commissioned by Governor Brisbane [6] in 1823 to accommodate the ever-increasing number of women entering the factory for diverse reasons, a three-class system came into effect. The three-class system brought greater order to the factory population, distributed its paltry resources on the basis of good behaviour and reflected its multi-purpose nature.

First-class refuge, labour exchange and marriage bureau

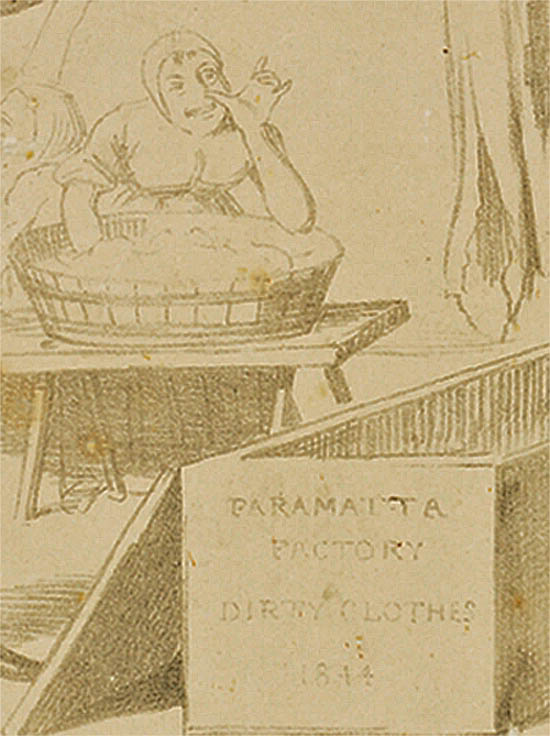

[media]For first-class women, the factory was chiefly a refuge and labour exchange. Typically, women of first-class status were newly arrived convicts needing accommodation and employment while awaiting assignment to a master. They received superior food and clothing, had visitation rights and the freedom to attend church while the tasks they performed were suited to their gender and station – wool picking, cloth scouring, carding, weaving, laundry for the military, needlework, cleaning and straw plaiting – and they could earn their own money for extra work they completed. [media]Women of this class were eligible for more than just employment, though, as they were also eligible to be chosen by a settler for marriage. This made the Female Factory, quite literally, a place where 'a proper person to have a wife given him' [7] could pick a woman off the production line. Such men were not always so 'proper'. More than one newly wed ex-inmate of the factory appeared in the 'Police Incidents' of the newspapers citing physical abuse at the hands of their husbands. [8]

Second-class halfway house

Second-class women were not yet eligible for assignment to a master for reasons ranging from motherhood to minor criminal offences committed while on assignment, and had inferior food and clothing, as well as fewer rights and privileges, than their first class counterparts. Since this was a probationary class, many second-class citizens of the factory may have been recently promoted from third class as they transitioned from third-class prisoner to first class employable servant.

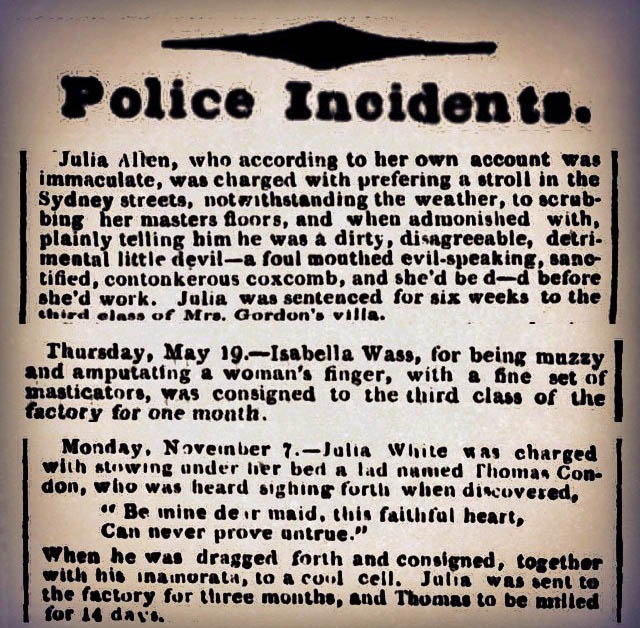

Third-class prison

[media]For those belonging to the-third class, the factory was unequivocally a harsh women's prison. Theoretically, the third class was reserved for those guilty of what were then deemed serious crimes but analysis of evidence related to sentencing shows that what was considered a serious crime was often not consistent. [9] In the case of convict Julia Allen, for example, 'prefering [sic] a stroll in the Sydney streets...to scrubbing her master's floors' and 'plainly telling him he was a dirty, disagreeable, detrimental little devil–a foul mouthed evil-speaking, sanctified, contonkerous [sic] coxcomb, and she'd be d–d before she'd work' was enough to earn her a sentence of six weeks in the factory's third-class. [10] On the other hand, when Isabella Wass was found guilty of the more violent crime of 'amputating a woman's finger with a fine set of masticators' the following fortnight, she was given two weeks less than Allen. [11]

Since the factory's opening in 1821, females of the criminal class were forced to complete hard labour more befitting male convicts and from 1826 had their heads shaved. In addition to humiliating the women by depriving them of what was seen as an essential feature of the female identities in this era, head shaving visibly identified the most disobedient members of the prison class, had long term effects on their prospect for reassignment and reduced their marriageability. 'It used to be the custom to burn the hair in [the] presence of the owner' post cropping, but it was not long before individuals employed at the factory found a way to profit from this practice. At the time of Julia Allen's incarceration in June 1831 The Sydney Monitor reported 'a traffic of a singular nature' was being 'carried on by some person attached to the Female Factory, namely the sale of the women's hair'. [12]

Solitary confinement was also common with additional cells being commissioned for this purpose in the 1830s by Governor Gipps.

Australia's first women's hospital

[media]A contrast to the brutality of the penitentiary element of the factory was the medical care available on site in a medical and maternity hospital designed by Greenway which still stands. Here, sick and injured women of all ages and, more often than not, expectant mothers (free or otherwise) received care. As such this was the first dedicated female health service in Australia. [13]

Children born in the factory hospital to convict and/or destitute mothers were permitted to stay with them until the age of three (but often younger) at which time they were sent to nearby orphan schools such as the Male Orphan School at Liverpool and the Female Orphan School now part of the University of Western Sydney campus at Rydalmere. However, as the burial records for the parish of St John’s attest, often infants born at the factory never knew anything of the world beyond its walls as they died before they were even old enough to be transferred to the orphan schools. Many women also passed away during their incarceration in the factory likely from infectious diseases and complications during childbirth. There was also at least one officially recorded case of death by starvation, although the authorities proved eager to quickly reverse that particular coronial finding; a strong indication that death by starvation was probably frequently covered up in this government institution. [14]

Riots

[media]At its best, the factory conditions were harsh but when severe overcrowding, bad management and reduced rations were added to the female convict experience, riots broke out. The first of these occurred on 27 October 1827 with many of the women wielding pick-axes, storming the gates and pouring onto the streets of Parramatta like 'Amazonian banditti,' [15] according to one contemporary journalist. Historian and heritage consultant Gay Hendrikson asserts that this riot allows the site to claim another first in Australian history: the first female workers' riot.[16] Four more riots took place at the factory in 1831, 1833, 1836 and 1843. [17]

Post-factory history of the site

When transportation ceased in 1840, the Parramatta Female Factory gradually became redundant. By the end of that decade the last of the inmates earned their tickets of leave or freedom and only a few elderly, mentally or physically ill women remained. At this point, the site officially became the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, housing free and convict men and women diagnosed as criminally insane and mentally disabled. However, it also continued to be multi-purpose to meet the needs of an ageing convict population accommodating those who were invalid or paralysed, the sick, the elderly, and paupers (again, both free and convict). [18] In 1869, the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum was renamed the Parramatta Hospital for the Insane but was also known as the Parramatta Mental Hospital. To suit the needs of the psychiatric patients, between approximately 1847 and 1910 a number of the original Female Factory buildings were demolished and new buildings were built on the existing architectural footprints. The renovated building was referred to as the Parramatta Psychiatric Centre from 1915 until 1983 when the site became Cumberland Hospital. The campus has continued to provide mental health care services to the public and, since 1995, has been home to the NSW Institute of Psychiatry. [19]

Within the broader Fleet Street Heritage Precinct other institutions were established including an orphanage. Where children had previously been assigned to orphanages on the basis of gender, the 1840s saw orphanages become faith-based. In late 1840, construction commenced on a four-storey stone building adjacent to the Female Factory, which was to serve as a barrack-style Roman Catholic Orphan School for boys and girls. (The Female Orphan School subsequently became the Protestant Orphan School for boys and girls). By 1887, the Roman Catholic Orphan School became the Industrial School for Girls, which was later known as the (infamous) Parramatta Girls Home, Kamballa and Taldree Children's Shelter, and the Norma Parker Detention Centre for Women. Many of the individuals who lived and died in the nineteenth-century institutions on this site were buried in paupers' graves at the nearby All Saints Cemetery.

Extant buildings and features of the Parramatta Female Factory

Though the main barrack building of the Female Factory was demolished in 1883, local researchers theorise that its sandstone blocks were probably reused in the construction of a ward for 100 male patients of the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum [20]; an impressive building that dominates the site today in the former second-class yard of the factory. the sandstone blocks may not have been the only resources from the original factory to be repurposed at the time. It is possible, though not confirmed, that the clock which adorned the original Female Factory main building was also modified and installed in the Male Ward clock tower [21], while the Female Factory bell, which bears the date 1820 is now suspended above the clock inside the clock tower. As bells have historically been used to provide auditors with strong acoustic cues regarding behaviour [22], this bell would have been integral to the daily organisation and control of the enormous population of factory inmates.

The Female Factory's main gates were also demolished in 1909 to make way for government architect Walter Liberty Vernon's Main Administration Block, but part of Greenway's original 1818 exterior walls that Macquarie wrote about still stand.

The Greenway Hospital and Greenway's Matron's Quarters, storerooms and factory committee room are also intact, as are the third-class sleeping quarters and penitentiary yard. The 1830s courtyard walls and Gipps Courtyard remain with discarded convict stone in situ but without the solitary confinement cells. In other parts of the site, later buildings from the post-factory era were constructed over the building footprints of workshops, kitchens, and washhouses.

In 2010 local community members established the Parramatta Female Factory Action Group to prevent historically insensitive adaptive reuse of the factory buildings that would destroy the fabric of the site and prohibit public access. The group aims to raise awareness of the unique historical significance of the site, much of which is suffering from 'demolition by neglect,' and to lobby for its national and world heritage listing to ensure its preservation. [23]

References

Byrne, JC. Twelve Years' Wanderings in the British Colonies from 1835 to 1847, Vol. I. London: Schuze and Co, 1848.

Dunn, Judith. Colonial Ladies: Lovely, Lively and Lamentably Loose: Crime Reports from the Sydney Morning Herald Relating to the Female Factory, Parramatta, 1831–1835.Winston Hills: Judith Dunn, 2008.

Cameron, Michaela Ann. The Female Factory Online: A Searchable Database for the Historic Parramatta Female Factory, c.1802-c.1848. https://femalefactoryonline.org/ (2017)

Gojak, Denis, 'Convict Archaeology in New South Wales: An Overview of the Investigation, Analysis and Conservation of Convict Heritage Sites.' Australasian Historical Archaeology, 19, Special Issue: Archaeology of Confinement, (2001): 73–83.

Hendriksen, Gay. Conviction: The 1827 Fight for Rights at Parramatta Female Factory. Blaxland, N.S.W: The Rowan Tree, 2015.

Hendriksen, Gay, Trudy Cowley, and Carol Liston. Women Transported: Life in Australia’s Convict Female Factories. Parramatta, N.S.W: Parramatta City Council Heritage Centre, 2008.

Kass,Terry, Carol Liston and John McClymont. Parramatta: A Past Revealed. Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996.

Therry, Roger. Reminiscences of Thirty Years' Residence in New South Wales and Victoria, with a supplementary chapter on Transportation and the Ticket-of-Leave System. London: Sampson Low, Son, and Co, 1863.

Notes

[1] Denis Gojak, 'Convict Archaeology in New South Wales: An Overview of the Investigation, Analysis and Conservation of Convict Heritage Sites,' Australasian Historical Archaeology,19, Special Issue: Archaeology of Confinement,' (2001): 76; Judith Dunn, Colonial Ladies: Lovely, Lively and Lamentably Loose: Crime Reports from the Sydney Morning Herald Relating to the Female Factory, Parramatta, 1831–1835 (Winston Hills: Judith Dunn, 2008), 9

[2] Terry Kass, Carol Liston, and John McClymont, Parramatta: A Past Revealed, (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 59

[3] 'Government and General Orders, Government House, Sydney, 27th Jan. 1821. Civil Department,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Saturday 27 January 1821, 1, http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2180040/492895, viewed 27 July 2017

[4] Lachlan Macquarie, 'Appendix to the Report of Major General Lachlan Macquarie, late Governor of the Colony of New South Wales, being A List and Schedule of Public Buildings and Works erected and other useful Improvements, made in the Territory of New South Wales and its Dependencies, at the expence [sic] of the Crown from the 1st of January, 1810, to the 30th of November, 1821,' 30 November 1822, 'Enclosure marked A' in JT Bigge, Report of the Commissioner of Inquiry into the State of the Colony of New South Wales (New South Wales: House of Commons, 1822) http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1300181h.html viewed 24 June 2015; Terry Kass, Carol Liston, and John McClymont, Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 97–99.

[5] Roger Therry, Reminiscences of Thirty Years' Residence in New South Wales and Victoria, with a supplementary chapter on Transportation and the Ticket-of-Leave System (London: Sampson Low, Son, and Co, 1863), 217; Governor Hunter to the Duke of Portland cited in Gay Hendriksen, Conviction: The 1827 Fight for Rights at Parramatta Female Factory, (Blaxland, N.S.W: The Rowan Tree, 2015), 6.

[6] Carol Liston, 'Convict Women in the Female Factories of New South Wales,' in Gay Hendriksen, Trudy Cowley, and Carol Liston, Women Transported: Life in Australia’s Convict Female Factories, (Parramatta, N.S.W: Parramatta City Council Heritage Centre, 2008), 36

[7] JC Byrne, Twelve Years' Wanderings in the British Colonies from 1835 to 1847, Vol. I (London: Schuze and Co, 1848), 230–32

[8] Songwriter John Hospadaryk has explored the experience of a convict woman married off at the Parramatta Female Factory in his song 'The Female Factory,' performed as a medley with the traditional ballad 'The Convict Maid' by Chloe and Jason Roweth: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QSZB-52gdgk viewed 24 June 2016

[9] Judith Dunn, Colonial Ladies: Lovely, Lively and Lamentably Loose: Crime Reports from the Sydney Morning Herald Relating to the Female Factory, Parramatta, 1831–1835 (Winston Hills: Judith Dunn, 2008)

[10] 'Police Incidents: Julia Allen,' The Sydney Herald, Monday 9 May 1831, 3 http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/12843023, viewed 24 June 2015

[11] 'Police Incidents: Isabella Wass,' The Sydney Herald, Monday 23 May 1831, 3 http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/12843068/1527237, viewed 24 June 2015

[12] 'Domestic Intelligence,' The Sydney Monitor, Wednesday 1 June 1831, 3 http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/32075555/4294383, viewed 24 June 2015

[13] Terry Kass, Carol Liston, and John McClymont, Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 98; 'Life in the Factories', Convict Female Factories Research Association, https://sites.google.com/site/convictfemalefactories/life-in-the-factories, viewed 10 June 2014

[14] 'Coroner’s Inquest on Unidentified Woman, 16 March 1826,' Female Factory Online, https://femalefactoryonline.org/coroners-inquests/c18260316/, viewed 12 May 2017; see original 'No title,' The Australian, Thursday 16 March 1826, 3 http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/37073252/4248709 viewed 12 May 2017

[15] 'Riot at the Female Factory,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Wednesday 31 October, 1827, 2

[16] For a detailed investigation of the 1827 riot see Gay Hendriksen, Conviction: The 1827 Fight for Rights at Parramatta Female Factory, (Blaxland, N.S.W: The Rowan Tree, 2015).

[17] 'Parramatta Female Factory Friends,' Parramatta Female Factory Action Group, http://www.parramattafemalefactoryfriends.com.au/history/, viewed 10 June 2014

[18] Terry Kass, Carol Liston, and John McClymont, Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 136

[19] Agency Detail, Archives Investigator, State Records of New South Wales, http://investigator.records.nsw.gov.au, viewed 17 June 2014

[20] Geoff Barker, 'The Second Female Factory: 1818-1848,' Parramatta Heritage Centre Research Services, 28 July 2015, http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2015/07/28/the-second-parramatta-female-factory-1818-1848/, viewed 24 June 2016

[21] For more information about the original Female Factory clock and its history see Geoff Barker, 'Female Factory and the Thwaites and Reed Turret Clock,' Parramatta Heritage Centre Research Services, 7 August 2015, http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2015/08/07/female-factory-and-the-thwaites-and-reed-turret-clock/ viewed 24 June 2016

[22] Alain Corbin, Village Bells: Sound and Meaning in the Nineteenth-Century French Countryside (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998); Shane White and Graham White, The Sounds of Slavery: Discovering African American History through Songs, Sermons, and Speech, (Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press, 2005)

[23] 'Parramatta Female Factory,' Parramatta Female Factory Action Group, http://www.parramattafemalefactoryfriends.com.au/history/, https://sites.google.com/site/parramattafemalefactory/home, viewed 16 June 2014; See also Parramatta Female Factory Action Group, 'Parramatta Female Factory Needs Your Help,' YouTube, http://youtu.be/YxsOaXbctxU, viewed 16 April, 2014

This entry was revised to include new research and references on 27 July 2017.

.